“We have this great mental chemistry,” my client – let’s call her A – said, as she described how someone she was seeing had started this new thing where they sent very emotional songs and messages to each other. They are both in the creative field and while she has known him for a long time, they re-connected at a recent work event and became close. The evocative words of the emotional messages is just one of the many ways in which my client and this person in her life witness each other in moving, intense ways which is about their artistic personhood and mental life, not so much about physicality or intimacy. They send messages to each other if they read a striking line or passage from a book, and spend hours dissecting what a phrase in a poem could mean.

The following week, however, my client isn’t feeling so excited. She says her friend has suddenly disappeared, and she doesn’t want to ask him where he is and why he isn’t speaking to her. He has shared in the past that being a good father to his children is very important to him, and she doesn’t want to come in the way if there’s an emergency with his kids, or perhaps even his wife.

Ordinarily, she would be judged and cast as the vamp or ‘the other woman’ just for being involved with a married man. Professionals (therapists included) might not be so blunt. But perhaps they would point to how her childhood attachment problems are making her choose a man who can “never be hers” – as if marriage is the only thing that comes in the way of men’s emotional availability. I too took this position once, with a client who came to me around five years ago. At the time I was relatively new to the field, and it took me some time to understand the judgement beneath my jargon. My veiled attempts to steer my client away from the person didn’t go anywhere, and I had to admit that my strategy wasn’t working. Then, I was propelled to take a different tack: to focus on what it was about this relationship that was cherished by this older client. When I took this road, the client opened up and shared what worked about that relationship and why they wanted to preserve it. To the heart, it doesn’t matter if a relationship has social approval. I was able to learn so much about how relationships work. That relationships have a pull because they hold both the reminder of our old wounds as well as the promise of their healing, and also that human beings are wired to be around each other, to love deeply, even if those relationships or feelings don’t fit into our personal or social categories.

Besides, my (present day) client A, is quite happy with the way the relationship is. She has no desire to marry him. Yes, there is discomfort at times, because she remembers that he has a conventional, normative family to go back to while she doesn’t. Does she want to leave her current life and marry him? Probably not. What matters to her is that he makes her feel like her thoughts and ideas have value, and she has value. He’s never been cruel to her. In fact, he would have gladly continued an intense friendship and not even named this a romance if my client had not. In one of our earlier sessions when she had just met him, she said, “I don’t feel like I need to possess him, keep him around. I feel so free. I feel like this is how I am accessing my queerness, because I don’t need him to marry me. I am loving him in such a free way. I am just glad for the way we reinforce each other’s creativity”.

Perhaps my client’s relationship is questioning what we were all born with – that there is only one right way to do relationships. Her relationship often questions the idea of “What does the right thing to do mean?”, and by default also turns the question to us, as therapists – what is therapy? Is it about making people conform? Is it about creating new rules of right and wrong which may not be like the old oppressive rules, but are still oppressive and normative in their own ways?

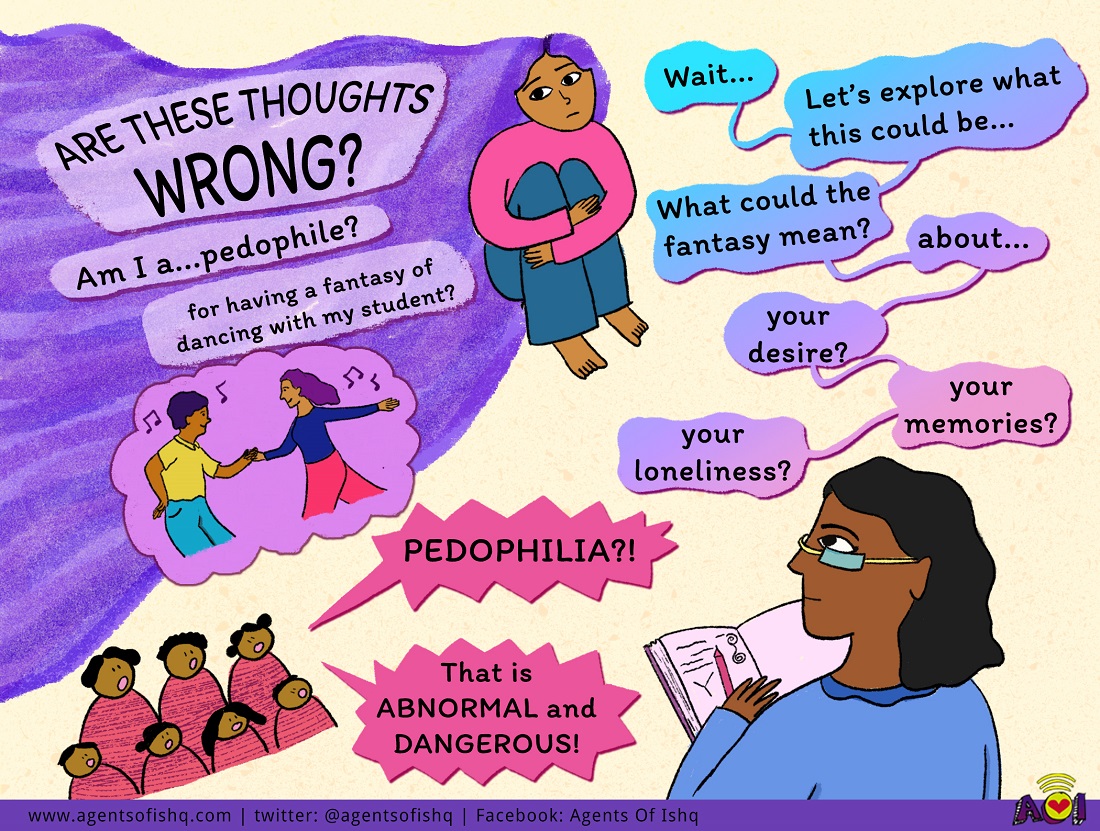

Another client, who is a devoted teacher, absolutely loves her students and is very interested in helping them develop a critical thinking even if they use it to question her. She was very troubled by a fantasy she began to have about one of her older students – of them Latin dancing together. This had startled her and she explained to herself that maybe it's because a lot of 12th grade boys tend to look like adults, thought legally they aren’t. But even while giving herself this explanation, she felt extremely guilty. “Do such thoughts make me a paedophile?” she asked. As a professional, it would’ve have been very easy for me to start moralizing and confirm her fears or start working with her to “control these urges”. To be honest, a part of my mind did go there and think of the politically correct thing to do. But something held me back. It was a feeling of “Wait, let’s explore what this could be…”

And so, what she and I did instead, was try to understand what her fantasy could mean. Did it tell us something about her loneliness? About her relationship with desire which had become fraught after she called off her marriage and had had no dating prospects that worked out since? Or perhaps, as she herself said, “The male gaze of these boys, I don’t return it. And as a feminist I even find it odd. But still, my 16-year-old self who thought she was ugly, that girl, finally feels vindicated”.

A conversation ensued on how, her college-time feminism was both a response to being bullied in school for being ugly, a way to say “I don’t need beauty, I have the power to fight for my rights, and that is what will anchor me”, and also a way to have another currency (intelligence, activism, seeing through the world’s illusions) apart from looks, in which to dwell and find self-worth and relational worth. The hurt of rejection could be processed by creating an inner circle of one’s own, which cares about different things. However, in the process, some ideas had become rigid, like what qualifies as toxic or abusive behaviour in relationships. The client told me that she actually liked it when her ex-partner would get slightly possessive and jealous. However, she could not allow herself to even say she liked it because of the strict interpretation of feminism she had picked up in college – and perhaps often vocalised. Could something we seek as a refuge or a response to a tough situation, be over-defined and become rigid in itself, trapping us? And if yes, can we redefine some of these ideas?

If her college feminism and other mental health professionals also inculcate shame in her, for her feelings towards the students, instead of looking at her as an imperfect human who can change, then how is this new shame any different from the older shame imposed on women for not being good enough?

When we reflected on this together, it helped us realise the bind of certainties, binaries and neat boxes. While life is messy, knowing the shortfalls of these imposed ideas (new or old) also helped us to feel a certain sense of freedom and compassion for her position and from that place, we were able to think of ways to bring desire back to her life and let go of, or at least hold lightly, some of the ideas that were feeling claustrophobic to her.

And as for me, as a therapist, as I let go of these fixed frames, and tried to make sense of the client’s experiences, a new understanding of what is ‘empowerment’ emerged. After all, how can something be empowering (ergo feminist), if it falls prey to rigid rules? Isn’t empowerment a term for the freedom to make new choices as situations change?

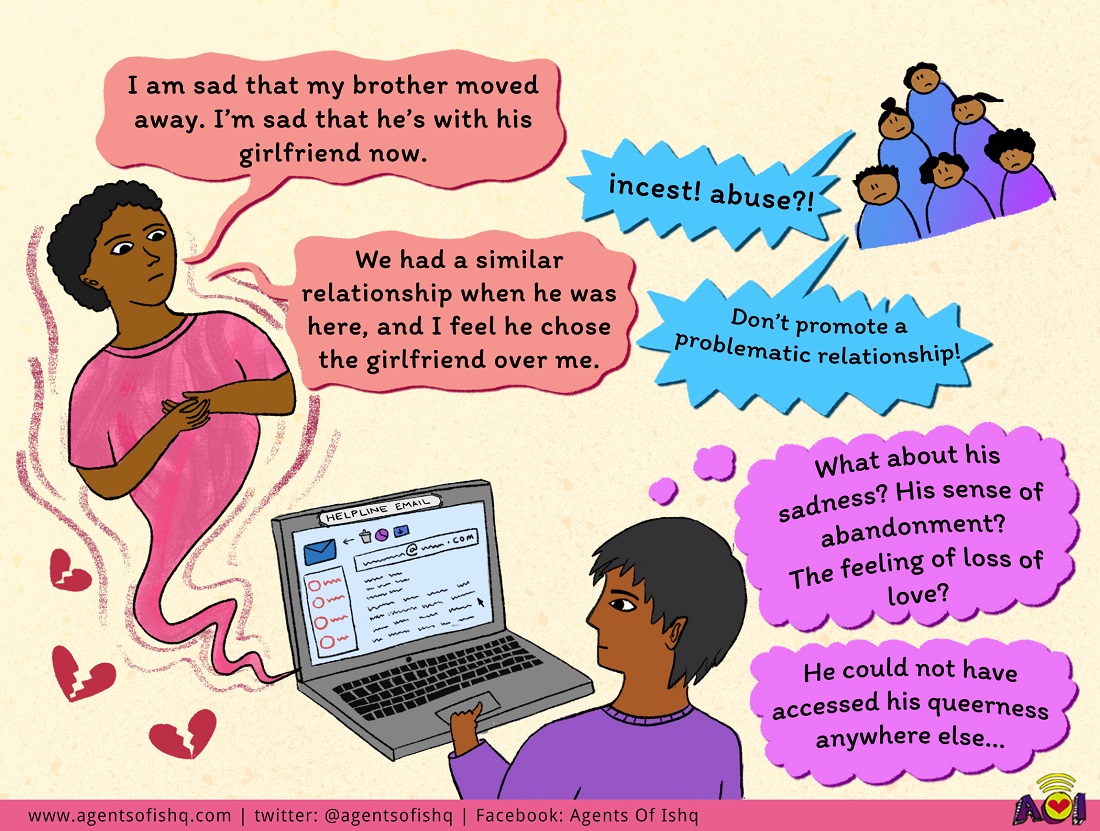

My colleague and co-founder of Guftagu, Aryan, shared a similar experience from his time working at a helpline that also had an option of email. “The client sent the helpline an email, where he spoke about his sexual experience with his brother. But, the point of distress he shared was about the brother moving to a new city, losing touch and not giving him that importance any more. The counsellor who attended to the email before me, responded with ideas of consent and abuse, hinging on incest. But when I read the email, I could also see the feelings of loss and grief and betrayal. He was missing the brother’s touch, the intimacy and the emotional closeness. In his eyes, he was in a relationship with the brother, he was madly in love with him, and was his ‘wife’. He felt accepted and loved. In his mind, it was a legitimate relationship and one where he thought, even at a distance, the brother would miss him. But unfortunately, none of that happened. He felt used, ignored, unwanted. He was grieving the loss – perhaps also at not being seen by his brother, the way he saw his brother.

“It was quite painful to read – his first love, first sexual experience, first access to his own queerness - and his feeling abandoned. I tried to respond to the email with acceptance of these emotions, talking about how this relationship helped him recognise his queerness and therefore, how the feelings of loss are quite valid. No matter how it happened, in this first experience, there was also a way to share that queer loneliness about being ‘abnormal’ or different, before it hit that this was a bubble. That doesn’t mean the bubble was not unique or lovable, a fairy tale for him, that naturally, he was grieving. When someone breaks this fantasy (a reality of queerness in itself), moves away and tells you to forget all this, you suddenly see the ugly unaccepting world – imagine the shock! This is what I tried to respond to.

“However,” Aryan said. “I wasn’t allowed to respond that way. The organization and my senior told me that I had to label the relationship as incest/abuse and write on the lines of safety and harm reduction and not ‘promote’ a problematic relationship. They said this has nothing to do with queerness, and I am normalizing abuse”.

Helplines can get into binaries and solution-focused modes because of the nature of the work - which tends to be crisis oriented. However, a solution focus can quickly turn into judgement, black and white thinking, and taking away a client’s agency and discard lived experience in the belief of educating them and being helpful.

Unfortunately, this sort of a stance, in professionals and organisations, is quite common. We grow up learning what is socially okay or not okay (e.g., incest is not okay, extra-marital relationships are not okay) and most of our training does not help us unlearn it, but rather teaches us to focus more on studying why people may not be falling in line and what can be done to get them to conform. A “moral panic” is induced. We feel like the order of society is shaken and it is our responsibility to bring it back and that this will protect the client/patient. However, most clients/patients need us to listen to their complex realities, not fix them. So, the lines get blurred – are we here to enforce morality or to promote the well-being of the person in question?

Does this mean the lens of harm has to be done away with completely? Of course not. Because in many cases, actual harm may be happening in relationships. For example, in India it is quite common that my clients had mothers who had been ill-treated by their husbands or in-laws. The clients are acutely aware of this. This often translates to them not wanting to see if, for instance, their mothers resent their children’s happiness and individual identity; that they might create guilt and shame if their child wants to do something the mothers don’t approve of. This is hurtful and, in many cases, harmful too. A trans client of mine was made to feel this way by his mother. She would say if he did gender-affirming transitions, he would be responsible if she had a heart attack or an upshoot in her diabetes, due to the shame of this upsetting news. She would often tell him, “Why don’t you do this process after I die? Just a few years more… At least then I will not have to be humiliated by people.” It was tough to untangle the love and care from these difficult, harmful behaviours.

Some harm, some hurt is part of every relationship, as our jagged edges collide. We won’t always agree on things and sometimes the disappointment can hurt quite deeply as it brings up our older, stronger unmet needs. However, the key lies in identifying where we are on the hurt/harm continuum. Hurt/harm is hardly ever a yes/no question. We need to figure the intensity, the intention and most importantly – our capacity to change. Most of us grow up seeing unhealthy behaviours in our families and without realising, model them in our own relationships. But if made conscious, do we work on them? Do we give our relationship what our parents did not get from each other and the society around us? If not, perhaps that situation could be harmful for one/both/all the people involved in that relationship.

Doctors, psychiatrists, therapists, lawyers and many such professionals often frown upon, make fun of or judge extra-dyadic relationships like relationships outside of marriage, polyamorous relationships, relationships with age gaps, with authority figures, with family members, open marriages and so on. The team members of Guftagu resonate that many clients have shared with them stories about their relationships which they cannot share with anyone else – family, friends or even other professionals. They feel they will be shamed. Perhaps shaming is the impact of the professional community’s default way of dealing with the inherent “messiness” of situations which have no existing social script, like there is for institutions like marriage. And often the rationale that results in shaming is that, as professionals we should help our clients make the right choices and not get into a soup, or lead to problems vis-à-vis society at large.

However, who are we to decide harm absolutely? How do we know if our idea of harm is not coming from our own social location?

For example, before homosexuality was removed from DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) diagnosis, professionals would provide conversion therapy or make their displeasure of gay relationships full of the belief of “helping” people. Even if we feel one or the other person in that relationship is being harmed or abused, will passing judgement help? Conversations on what power means, what the age gap or power differential could mean, how consent can be better negotiated, care, respect and so on, are more likely to be helpful, as they help us reflect on the extent of hurt/harm, if any, and also allow for a multiplicity of ideas beyond just harm or abuse, arrived at together with the client. It can help us see enlivens the person about the relationship in question. Understanding where their pleasure lies, will help us help them far more than deciding what harm has been done to them from our fixed position.

We all bring our past, its unmet needs, patterns, defences and wounds into newer relationships. If the new relationship was not a fertile ground to grieve the losses of older ones, perhaps it would not have the kind of pull it does. As we are engaged by films or novels, that mirror our personal dilemmas and tough experiences, so too we are often attracted to people who have the potential to make us reach older wounds and unknown parts of ourselves. It is this sense of intrigue and mystery which is the hot spring of desire. And this inexorable mix of attractions and mystery, comfort and safety which can help us understand ourselves better, is un-served if it is simply categorised according to a binary of bad or abusive, without complexity.

Are we really being progressive if we cancel people, relationships or relationship practices? Or do we simply replace old rules with a new form of normative control, which outcasts people emotionally and socially, as we decide if their relationships, lives, feelings are “real” or “valid” or “not problematic”.

The answer to such a complicated question seems to be in more than one place, as it should be. Our brains are wired to think in two ways - fast and slow. The fast one helps us survive – but it also relies on shortcuts for efficiency. Categories and enforcement soothe that part of our brain and also favour larger systems like marriage, capitalism, patriarchy, parenting that depend on these binaries to control us. Woke positions can sometimes become similar controls, if they aren’t interested in nuance and curiosity -- the two elements that breathe life and love into relationships.

Our emotional and relational lives are quite complex and rich. As therapists, if we can resist quick binaries of harm and health and enter into a deeply curious relationship with the clients we serve, we may be led down unmarked paths, to a different, perhaps more joyous world.

Sadaf is a therapist with 7 years of experience working with individuals, couples and families using a nuanced, depth-oriented approach. In her free time, she likes to engage her curiosity in writing, reading, baking, art and chilling with her cats.