Looking towards an epic about abduction and marital jealousy for love advice - really? Well, that depends on how you choose to read it – and what you choose to read. It’s a mistake to call it “The Ramayana” as though there is only one. There are songs both never recorded and found on Youtube, there are oral narratives, there are theatre and dance performances, there are films – and of course, there are texts in many languages.While researching many Ramayanas (as the scholar A.K. Ramanujan put it: “How many Ramayanas? Three hundred? Three thousand? At the end of some Ramayanas, a question is sometimes asked: How many Ramayanas have there been?”) for my new book of poems, I discovered some wise counsel for matters of the heart….

Sharanya Manivannan is the author of the award-winning short story collection, The High Priestess Never Marries. Her latest book of poems is The Altar of the Only World.

Sharanya Manivannan is the author of the award-winning short story collection, The High Priestess Never Marries. Her latest book of poems is The Altar of the Only World.

1. “To bring a man back, don't follow him too far.” – Rama the Steadfast (Sanskrit, translation: John Brockington & Mary Brockington)

These words are actually spoken to King Dasaratha when his son, Rama, is exiled. But when I read them, I went hey. Perfectly sound advice that could just as well have been on Sex and the City.This early Ramayana was told in a distinct Sanskrit dialect, and its authorship is uncertain, which would make the sage Valmiki a sort of meta-fictive character. Brockington & Brockington, who worked with the Baroda Critical Edition that was compiled over 25 years, are certain the lack of empathy towards women in the text could only mean that the author was a man. Which brings us to….

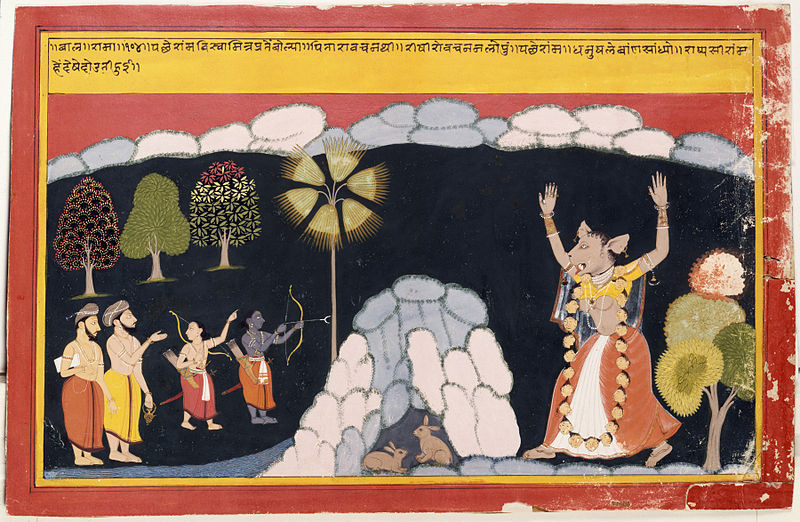

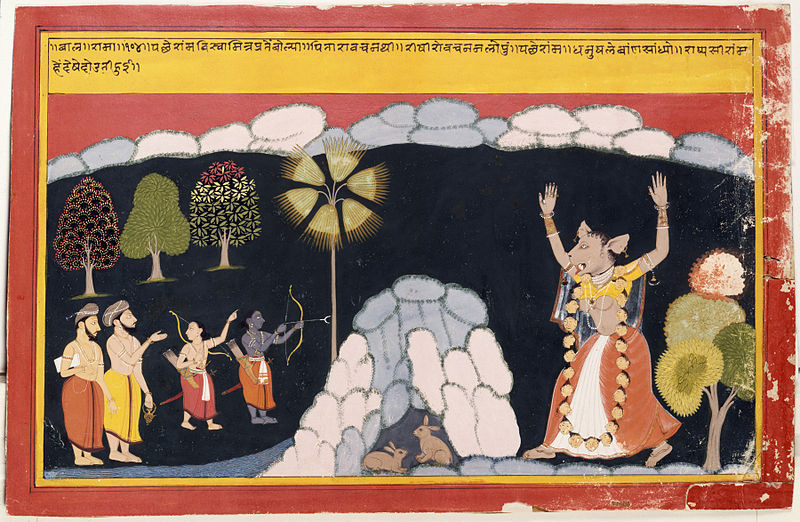

2. “She who is mother to all three worlds, / you say such things to her in your lust, / I do not see how you will survive.) – Adbhut Ramayana, Saudamini Devi (Bengali, translation: Arjun Chaudhuri)

Misogynists, watch out. Women everywhere – in all the three worlds, if you like – are speaking out, and we’re done with the patriarchy. Take the warning and apply it to your love life if you’re a heterosexual man (some hints: there’s no such thing as a “friendzone”, you’re not entitled to sex with anyone, and emotional abuse is abuse). These lines are spoken by Sita, about herself – on the battlefield. Where she turns into Kali and slays the powerful man who’s propositioning her.The Adbhut Ramayana is another Sanskrit work attributed, as several are, to Valmiki. It is significantly different in plot from the most popular modern telling, which is based on the saint Tulsidas’ Awadhi-language Ramcharitmanas. In it, after a triumphant return to Ayodhya, Sita tells Rama that his defeat of Ravana was cool and all, but the Lankan king had an even more powerful older brother. Egos stoked, the army returns to the island – where it turns out that none but Sita herself can handle the enemy. This Bengali rendition is by Saudamini Devi, who had a brother named Rabindranath Tagore.

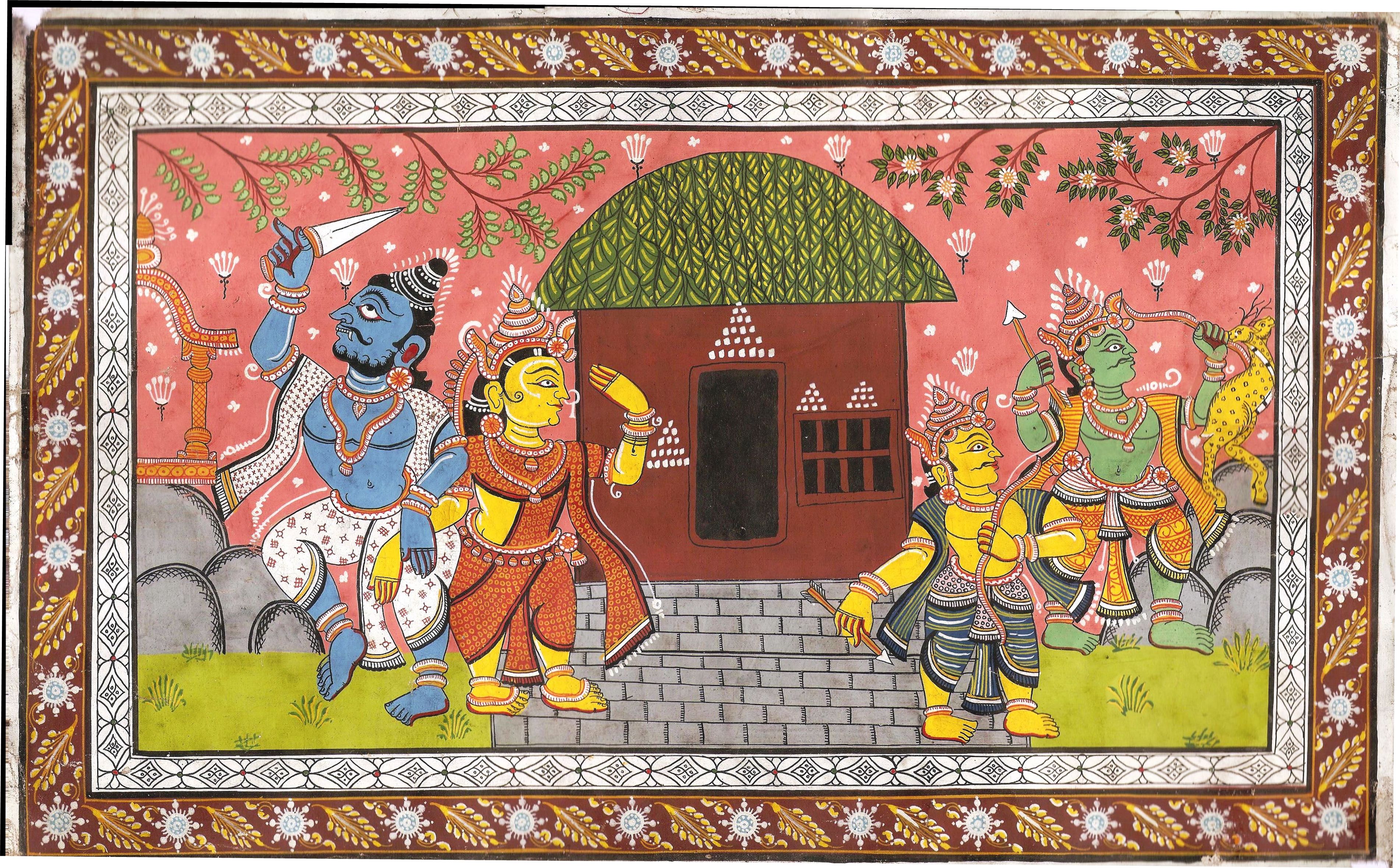

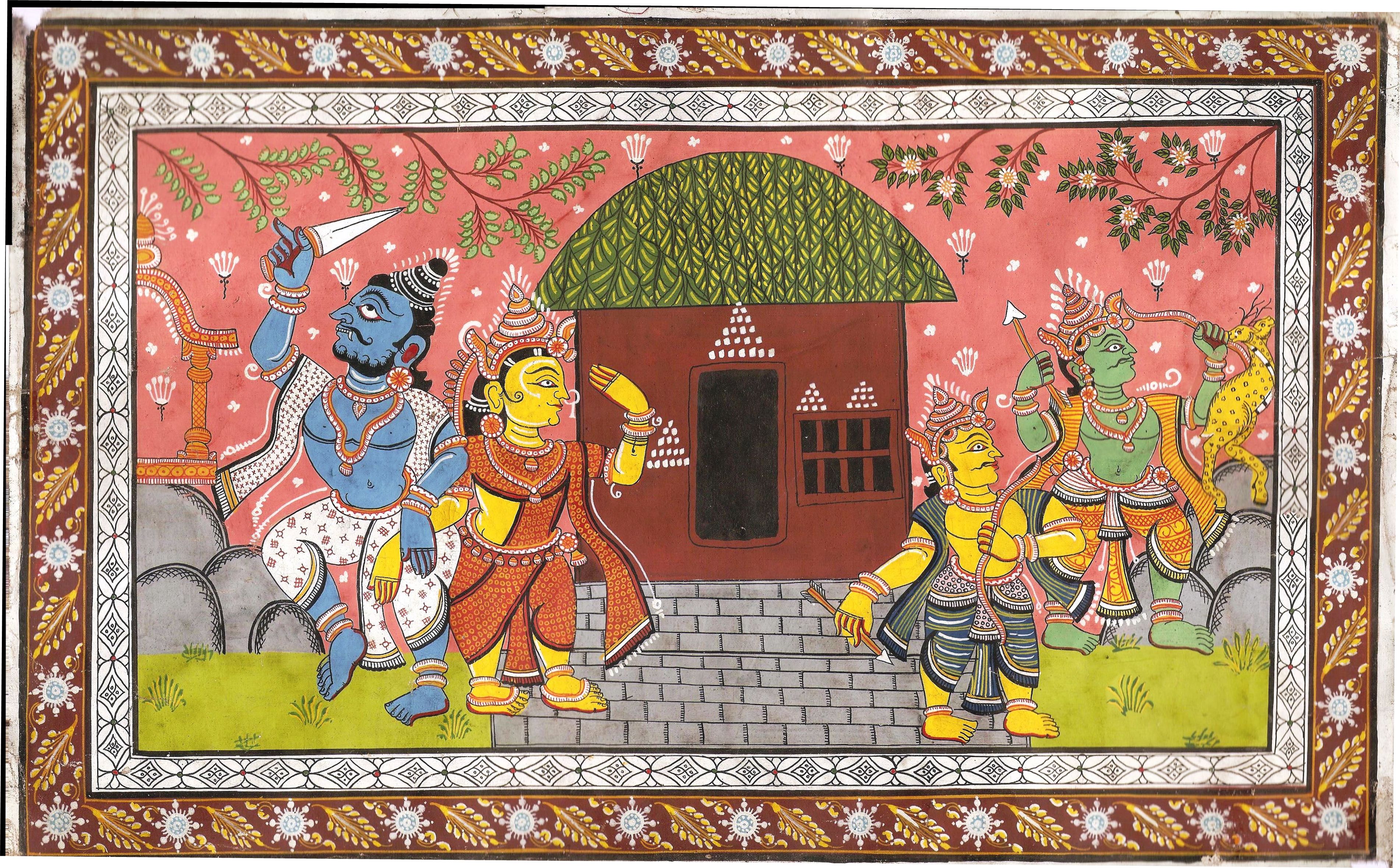

3. “Kama [Lust] is the source of the whole world; it’s impartial… Get rid of kama and there’s no balance.” – Malayalam shadow theatre, based on the Tamil Kambaramayanam (translation: Stuart. H. Blackburn)

Goddess temples in central Kerala still have performances of shadow puppetry in which cantos from the poet Kamban’s Ramayana are sung, followed by commentaries as well as verses of unknown origin. In the sequence in which Surpanakha propositions Rama and Lakshmana, she laments about the intensity of her desire in Kamban’s words, after which this forthright commentary is offered. Desire makes the world go round – and that’s nothing to be ashamed of. As long as it’s consensual.A quick note about the Kambaramayanam – it is quite sensuous and full of revelry (sample this verse, translated by Chenthil Nathan: “Women whose tresses were/ adorned with fragrant flowers, / oil and incense, drank clear toddy/ that kindled the fire of lust in their heart,/ like ghee poured into the homa fire pit.)

4. “…with their honeyed words they can snatch the loin cloth away from the greatest hermit” Ramayanamu, Molla (Telugu, referenced by Nabaneeta Dev Sen)

The courtesans of Ayodhya – at least in Molla’s description of them – knew that speech is an aphrodisiac. From the timbre of the voice, to the possibilities of repartee, to whatever the ancient version of sexting was – the brain is erogenous, after all. Molla was a potter and poet who challenged caste norms by writing her own Ramayana in the 16th century. She remains well-known in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, but her work (like so many fascinating renditions) hasn’t been widely translated. What is suggested by scholars like Nabaneeta Dev Sen, who did vital work in women’s oral and textual Ramayana renderings, is rather delicious though…

5. “Every one and everything coming in my garden should render respect and homage.” Rama Kakawin (Javanese, translation: Soewito Santoso)

Some of us like Ravana just a little because you could argue that he respected Sita’s choice not to consent to his sexual advances (but those are still pretty low standards, given the abduction and all). So when Ravana responds with the line above to news of Hanuman’s wrecking the ashokavanam, you kind of have to give him props for being consistent and expecting that spaces be mutually respected. It’s a pretty good principle to live by: demanding the respect you deserve. From everyone, but especially those you let into your “garden” – whatever that means to you. And speaking of Hanuman, if the existence of a Javanese Ramayana surprises you, you’ve got to look up what he does in the Thai Ramakien. Brahmachari who?

6. “To heed another’s gossip is to bring ruin upon oneself.” - Ramayana, Chandravati (Bengali, translation: Mandrakanta Bose)

The author of this 16th century Sitayana listened to a lot of stories, for sure – her version includes the distinctly non-canonical view of Sita as the child of Ravana’s wife Mandodari, after the latter consumes a grail of blood. Chandravati chose which stories to pay attention to, positing women’s suffering first (rather than dharma, lineage or glory, as in the more famous Ramayanas), paying no heed to what others might say – and even rebuking Rama himself with this mid-text authorial intervention.It’s worth noting that Chandravati is said to have started writing her interpretation after being abandoned on her wedding day, channeling pain into creativity (now that’s a great tradition). A refrain she uses is “suno sakhijana” ("listen, girlfriends") – she unabashedly wrote for other women, not for a royal court or a general audience.

7. “Break off the engagement, father. I’d much rather stay unmarried.” Bhojpuri folksong (translation: Smita Tewari Jassal)

In this folksong, Sita says these words right after her father describes Rama’s great beauty to her and her mother. It may seem like a strange twist in a passage of praise, especially as compared to numerous traditional wedding songs which invoke Sita and Rama’s marriage as an ideal. But perhaps, given the discrepancy between those and how the epic actually unfolds, it’s those other paeans that are stranger still.This Sita knows her own mind. Does this man have nothing else going for him but hotness (literally, her dad says, “The sun was made in Rama’s likeness”)? Swipe left.

8. “Ram has given me this gift of exile / Like a sudden gust of wind...” Marathi folksong (referenced by Nabaneeta Dev Sen)

The canonical Ramayanas are available easily as books and translated widely, but the many ways the story is internalised and expressed in songs and oral narratives are not. In Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s lecture, “When Women Retell the Ramayan”, she shares lines from various folksongs, which were often used by women to express the personal tensions by sublimating it into the epic.Maybe the formal poets didn’t codify this fact, but many illiterate women weren’t afraid to sing it straight-up: being rejected by an unworthy partner always turns out to be a good thing.

9. “You give me your bows and arrows / I will go right now and get the animal.” – Telugu folksong (translation: Velcheru Narayana Rao)

There’s something to be said for questioning our interlocuters. In Velcheru Narayana Rao’s essay, “A Ramayana of Their Own: Women's Oral Tradition in Telugu”, he decides to make an uncomfortable distinction between Brahmin and non-Brahmin women, and focuses extensively on the first category. But the songs themselves make a more radical distinction: the upper-caste women’s songs are full of internalised misogyny, like instructions for new daughters-in-law, while the songs of the field and daily labour contain frank, empowered statements like the one above. In this folksong, Sita says she’ll go hunt that golden deer herself if she has to; an ego-bruised Rama immediately sets forth. This Sita goes after what she wants. [For more contrast, though certainly not recommended as romantic guidance – from a Himachal rendition, Ramkatha ke Loprasang: “I’ll break your bow/ And your five arrows! Either bring the deer/ Or I’ll die, you hear?” (translation Meenakshi Faith Paul, “Sita in Pahari Lok Ramain”).]

10. “What is the use of being jealous? A wife is a woman; a woman is a woman; and a man cannot be in two places at once." The Ramayana, As Told by Aubrey Menen, Aubrey Menen (English, 1954)

Aubrey Menen’s novel was the first book to be banned in modern India, and it also happens to be a hilarious satire on religious hypocrisy. In it, a droll and dissident Valmiki tells Rama a series of fantastical tales with the intent of enlightening him, including one about four fishermen obsessed with the idea that their wives are cheating on them. They finally receive the advice above, from no less than a divine source – there’s no point in being so possessive that you neither work nor sleep (nor love!) well. Imagine a version of the Ramayana in which Rama accepts it. Sharanya Manivannan is the author of the award-winning short story collection, The High Priestess Never Marries. Her latest book of poems is The Altar of the Only World.

Sharanya Manivannan is the author of the award-winning short story collection, The High Priestess Never Marries. Her latest book of poems is The Altar of the Only World.