What does ‘intersex’ mean? Why does it remain something that we know so little about, and what can we do to change this? We spoke to Bindumadhav Khire, a queer rights activist, founder of the Samapathik Trust in Pune, and author of the Marathi book Intersex: Ek Prathmik Olakh(2015) – a first-of-its-kind primer on intersex bodies and experiences in an Indian language – to find out more.

Why is being intersex such an isolating experience for many people?The biggest problem is of self awareness: “Who am I?” “What does it mean to be intersex?” “My parents may say that I am male, but my anatomy may not conform to what male organs are supposed to look like.” This uncertainty leads to a sense of isolation, because there is such little visibility for intersex people, especially in rural areas. An intersex person may not be able to identify themselves as belonging to a particular gender, or as transgender, or as heterosexual – so they do not know where to fit in. Intersex people do get left far behind.Another issue is the lack of a support system. There are many gay and trans support groups, some organisations even reach out to rural areas, but very few organisations actively include intersex people. Most queer groups remain limited to cities.So loneliness and shame takes over for intersex people – the feeling that “I am supposed to be ashamed of my body, it is something to be hidden, I do not fit into society.” There is always the fear that if their identity is disclosed to their friends and their colleagues, they might lose those friendships. Some pass as a particular gender, living with the fear that they can’t get married or have children because of their anatomy.

Why is being intersex such an isolating experience for many people?The biggest problem is of self awareness: “Who am I?” “What does it mean to be intersex?” “My parents may say that I am male, but my anatomy may not conform to what male organs are supposed to look like.” This uncertainty leads to a sense of isolation, because there is such little visibility for intersex people, especially in rural areas. An intersex person may not be able to identify themselves as belonging to a particular gender, or as transgender, or as heterosexual – so they do not know where to fit in. Intersex people do get left far behind.Another issue is the lack of a support system. There are many gay and trans support groups, some organisations even reach out to rural areas, but very few organisations actively include intersex people. Most queer groups remain limited to cities.So loneliness and shame takes over for intersex people – the feeling that “I am supposed to be ashamed of my body, it is something to be hidden, I do not fit into society.” There is always the fear that if their identity is disclosed to their friends and their colleagues, they might lose those friendships. Some pass as a particular gender, living with the fear that they can’t get married or have children because of their anatomy. Is there a sense of what percentage of people are born intersex? What makes the intersex community so invisible and underrepresented in the mainstream?Even among the sexual minorities, even compared to trans-men, who get such little attention compared to trans-women, they are a very small number. If you look at a population of intersex people in whose bodies the ambiguity is very clear-cut, they might form 1 in 1,00,000.Being such a small community, there are few people to highlight the issue, to empower themselves and stand up and say, look, I can be a role model for others. Perhaps that’s why achieving visibility is a long process.They also don’t have the same kind of cultural context and cultural advantage that the trangender community has – because the Hijra and Jogta communities have been culturally visible for so long, they are more recognised than even gay men or lesbians.How have medical practices fed into the shame and stigma that surrounds being intersex, and the idea that it needs to be hidden?One major problem faced by intersex people is sex assignment at birth. If a baby is born intersex and the parents can afford surgery, they immediately try to “correct” the ambiguity by altering the child’s reproductive organs to fit a particular gender.This can be a very problematic thing, because you do not know the gender identity of the child at that point, and you could be doing the wrong operation. And because the genitalia are not mature at that point, it can cause problems later. It also adds to the idea that there is something wrong with being intersex – that it needs to be fixed.

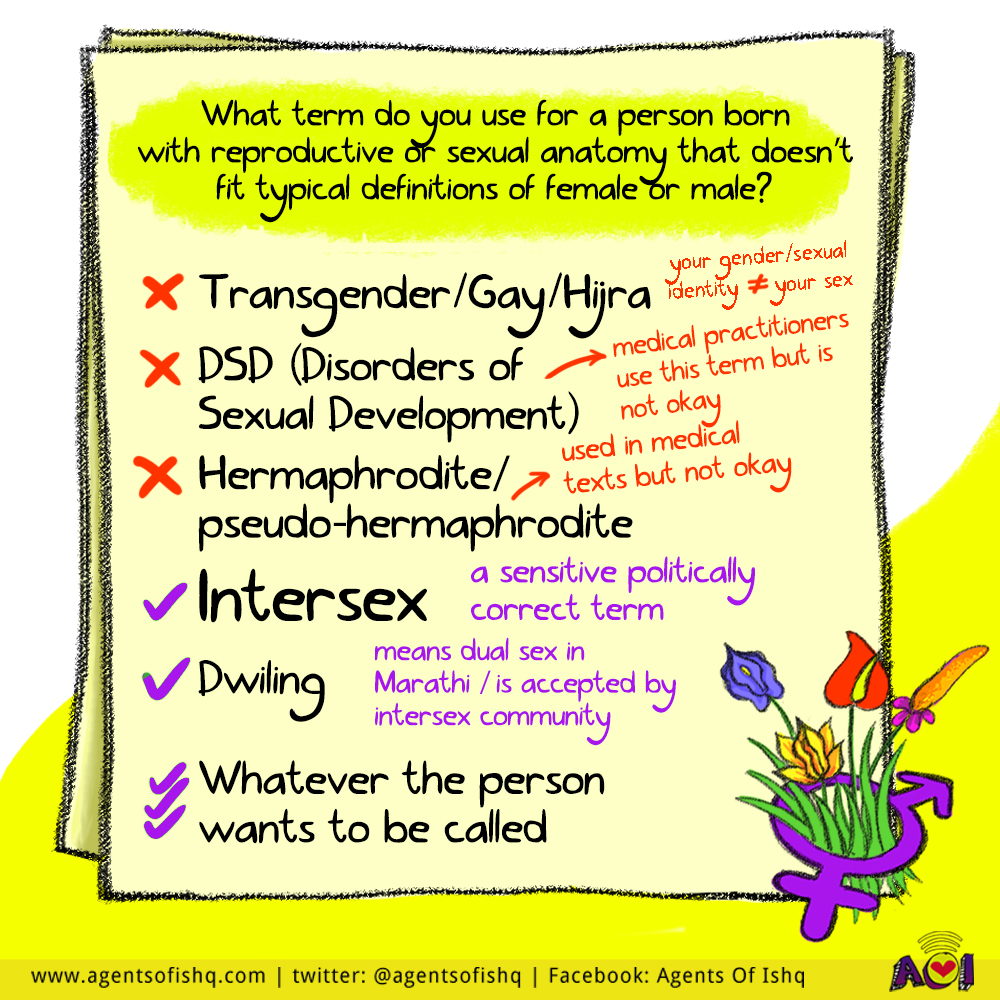

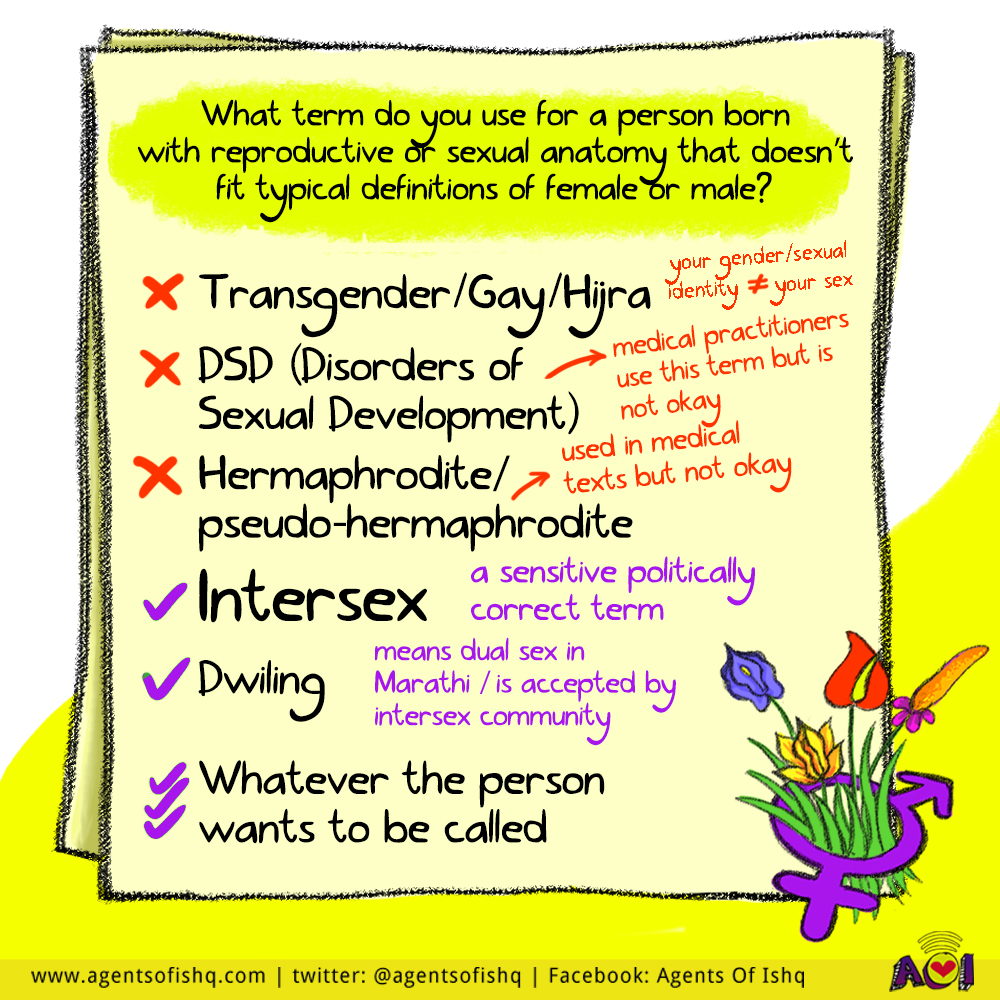

Is there a sense of what percentage of people are born intersex? What makes the intersex community so invisible and underrepresented in the mainstream?Even among the sexual minorities, even compared to trans-men, who get such little attention compared to trans-women, they are a very small number. If you look at a population of intersex people in whose bodies the ambiguity is very clear-cut, they might form 1 in 1,00,000.Being such a small community, there are few people to highlight the issue, to empower themselves and stand up and say, look, I can be a role model for others. Perhaps that’s why achieving visibility is a long process.They also don’t have the same kind of cultural context and cultural advantage that the trangender community has – because the Hijra and Jogta communities have been culturally visible for so long, they are more recognised than even gay men or lesbians.How have medical practices fed into the shame and stigma that surrounds being intersex, and the idea that it needs to be hidden?One major problem faced by intersex people is sex assignment at birth. If a baby is born intersex and the parents can afford surgery, they immediately try to “correct” the ambiguity by altering the child’s reproductive organs to fit a particular gender.This can be a very problematic thing, because you do not know the gender identity of the child at that point, and you could be doing the wrong operation. And because the genitalia are not mature at that point, it can cause problems later. It also adds to the idea that there is something wrong with being intersex – that it needs to be fixed. If you look at medical texts, even today they use terms like “hermaphrodite” or “pseudo-hermaphrodite”. These terms are considered to be degrading, and are denounced by intersex organisations across the world from a human rights perspective. The word that medical practitioners are increasingly using is DSD – Disorders of Sexual Development. Even this is something we do not want, the term ‘disorder’ is something that should be corrected.The terms considered acceptable for use by the intersex community are the terms that we all should be using. In Marathi, this is ‘dwiling’ – which means dual sex, and in English, the sensitive and politically correct term to use is simply, ‘intersex’.A recent order by the Madras High Court banned sex assignment surgery for intersex children, and the Tamil Nadu government has now enforced this as well. How do you see this?It is a good thing, I welcome it, but it has limited application. Parents who want to make their child go through surgery can take them to Karnataka or any other state and do it. We need the Central government to create an Act that stops this.At the moment we are very far away from having such a law. There is no understanding of the term intersex for most of the population, including the media, lawyers, judges, and doctors. Awareness is the first step, and without that there will be no sensitisation. And without sensitisation, people will not understand the injustices that intersex people face, and therefore make changes to fix this.

If you look at medical texts, even today they use terms like “hermaphrodite” or “pseudo-hermaphrodite”. These terms are considered to be degrading, and are denounced by intersex organisations across the world from a human rights perspective. The word that medical practitioners are increasingly using is DSD – Disorders of Sexual Development. Even this is something we do not want, the term ‘disorder’ is something that should be corrected.The terms considered acceptable for use by the intersex community are the terms that we all should be using. In Marathi, this is ‘dwiling’ – which means dual sex, and in English, the sensitive and politically correct term to use is simply, ‘intersex’.A recent order by the Madras High Court banned sex assignment surgery for intersex children, and the Tamil Nadu government has now enforced this as well. How do you see this?It is a good thing, I welcome it, but it has limited application. Parents who want to make their child go through surgery can take them to Karnataka or any other state and do it. We need the Central government to create an Act that stops this.At the moment we are very far away from having such a law. There is no understanding of the term intersex for most of the population, including the media, lawyers, judges, and doctors. Awareness is the first step, and without that there will be no sensitisation. And without sensitisation, people will not understand the injustices that intersex people face, and therefore make changes to fix this. What do you hope that people take away after reading your book, what do you want them to feel?My books on homosexuality, gender identity, my writing in various anthologies, and of course the intersex book all have the same theme – that even though statistically you are a minority, you are not abnormal. You are different from others, but do not feel ashamed of yourself and your sexuality, try to accept yourself, and try to if possible come out to trusted people about your sexuality.Don’t let your sexuality eclipse all other aspects of your life. What happens is that if you focus on and obsess only about sexuality, you are unable to focus on your talent and career and areas you would like to excel in. I want people of sexual minorities to be totally accepting of who they are, be proud of who they are, and show the rest of the world that although you may not accept my variation, I am as good as you and even better at the work I do, and I can challenge you on any and every platform where I feel I can excel and be part of the mainstream. The more we are outside the mainstream, the more we will be marginalised, and the more our rights will be ignored.

What do you hope that people take away after reading your book, what do you want them to feel?My books on homosexuality, gender identity, my writing in various anthologies, and of course the intersex book all have the same theme – that even though statistically you are a minority, you are not abnormal. You are different from others, but do not feel ashamed of yourself and your sexuality, try to accept yourself, and try to if possible come out to trusted people about your sexuality.Don’t let your sexuality eclipse all other aspects of your life. What happens is that if you focus on and obsess only about sexuality, you are unable to focus on your talent and career and areas you would like to excel in. I want people of sexual minorities to be totally accepting of who they are, be proud of who they are, and show the rest of the world that although you may not accept my variation, I am as good as you and even better at the work I do, and I can challenge you on any and every platform where I feel I can excel and be part of the mainstream. The more we are outside the mainstream, the more we will be marginalised, and the more our rights will be ignored. How can we be better allies to the intersex community?I think one way is gaining more knowledge – we need to understand the LGBTI spectrum. We should not use terms that the community sees as derogatory. We need to understand that none of these are disorders or perversions. We are all variations of nature and, there is vast diversity in nature. We should not try to change or alter people just because they are not like us.Yes, surgery is an option if they want to choose it, but in the case of a child, let them grow up to be an adult and decide for themselves whether they would like surgery.Does acknowledging intersex as a biological sex help us break out of the binary of sex as being only male or female? And does it fundamentally change the way we think about sex and gender and society?That is true, not just about anatomical sex, but about gender identity too. Because your gender identity is not binary – it can be male, female, fluid… and it is not determined by the organs in your body. Neither is your sexual orientation determined by anatomy or gender.

How can we be better allies to the intersex community?I think one way is gaining more knowledge – we need to understand the LGBTI spectrum. We should not use terms that the community sees as derogatory. We need to understand that none of these are disorders or perversions. We are all variations of nature and, there is vast diversity in nature. We should not try to change or alter people just because they are not like us.Yes, surgery is an option if they want to choose it, but in the case of a child, let them grow up to be an adult and decide for themselves whether they would like surgery.Does acknowledging intersex as a biological sex help us break out of the binary of sex as being only male or female? And does it fundamentally change the way we think about sex and gender and society?That is true, not just about anatomical sex, but about gender identity too. Because your gender identity is not binary – it can be male, female, fluid… and it is not determined by the organs in your body. Neither is your sexual orientation determined by anatomy or gender. What mindset change is needed to shift the needle on sex assignment surgeries at birth and why should we be rethinking that?The whole idea of sexual minority rights, or LGBTI rights, is to say – My body, my rights, my gender identity, my sexual orientation, and I don't care if others like it or not, I will decide what to do with it.So let the child become an adult, and let them decide whether they want to live as an intersex person or do surgery so their anatomy conforms to their gender identity. All we can do is support them as they are, and say, “We are with you irrespective of your sexual orientation, gender identity or anatomy, we are all human beings.” We must give them the same respect and dignity we give to all our loved ones.Let society not impose its morals on another person, forcing on them something they don’t want.

What mindset change is needed to shift the needle on sex assignment surgeries at birth and why should we be rethinking that?The whole idea of sexual minority rights, or LGBTI rights, is to say – My body, my rights, my gender identity, my sexual orientation, and I don't care if others like it or not, I will decide what to do with it.So let the child become an adult, and let them decide whether they want to live as an intersex person or do surgery so their anatomy conforms to their gender identity. All we can do is support them as they are, and say, “We are with you irrespective of your sexual orientation, gender identity or anatomy, we are all human beings.” We must give them the same respect and dignity we give to all our loved ones.Let society not impose its morals on another person, forcing on them something they don’t want.

Still from Main Aur Meri Body

What is intersex?Intersex is an anatomical variation that you can either see, if the external genitalia is ambiguous, or find out by testing for chromosomal or hormonal variations or getting an ultrasound which can show you the variations in internal sexual organs.This is not the same as being trans, which is a question of gender identification. A trans person may be born male or female or intersex, but identify as another gender.Why did you feel it was important to work on a book about intersex bodies?Through my work as an LGBT activist I have met intersex people and I was aware that they felt a lot of uncertainty about their identity, and there was no information about it in Marathi. While people are at least aware of LGBT terminology, they know very little about what intersex is. Intersex people themselves are sometimes unsure about their identity and what the Marathi terminology is for it. Some have never heard of the word ‘intersex’, and they do not know whether there are any other people like them.That’s why I wanted to write this book. It is a 100-page primer in Marathi on intersex bodies. It covers the basic information about being intersex, like how reproduction happens, how variation in chromosomes or hormones can happen, what are the different types of intersex bodies, etc. The book also looks at common medical practices, the law, nomenclature and correct practices, approached from an Indian perspective, and includes conversations with some intersex people who shared their stories and experiences. Why is being intersex such an isolating experience for many people?The biggest problem is of self awareness: “Who am I?” “What does it mean to be intersex?” “My parents may say that I am male, but my anatomy may not conform to what male organs are supposed to look like.” This uncertainty leads to a sense of isolation, because there is such little visibility for intersex people, especially in rural areas. An intersex person may not be able to identify themselves as belonging to a particular gender, or as transgender, or as heterosexual – so they do not know where to fit in. Intersex people do get left far behind.Another issue is the lack of a support system. There are many gay and trans support groups, some organisations even reach out to rural areas, but very few organisations actively include intersex people. Most queer groups remain limited to cities.So loneliness and shame takes over for intersex people – the feeling that “I am supposed to be ashamed of my body, it is something to be hidden, I do not fit into society.” There is always the fear that if their identity is disclosed to their friends and their colleagues, they might lose those friendships. Some pass as a particular gender, living with the fear that they can’t get married or have children because of their anatomy.

Why is being intersex such an isolating experience for many people?The biggest problem is of self awareness: “Who am I?” “What does it mean to be intersex?” “My parents may say that I am male, but my anatomy may not conform to what male organs are supposed to look like.” This uncertainty leads to a sense of isolation, because there is such little visibility for intersex people, especially in rural areas. An intersex person may not be able to identify themselves as belonging to a particular gender, or as transgender, or as heterosexual – so they do not know where to fit in. Intersex people do get left far behind.Another issue is the lack of a support system. There are many gay and trans support groups, some organisations even reach out to rural areas, but very few organisations actively include intersex people. Most queer groups remain limited to cities.So loneliness and shame takes over for intersex people – the feeling that “I am supposed to be ashamed of my body, it is something to be hidden, I do not fit into society.” There is always the fear that if their identity is disclosed to their friends and their colleagues, they might lose those friendships. Some pass as a particular gender, living with the fear that they can’t get married or have children because of their anatomy. Is there a sense of what percentage of people are born intersex? What makes the intersex community so invisible and underrepresented in the mainstream?Even among the sexual minorities, even compared to trans-men, who get such little attention compared to trans-women, they are a very small number. If you look at a population of intersex people in whose bodies the ambiguity is very clear-cut, they might form 1 in 1,00,000.Being such a small community, there are few people to highlight the issue, to empower themselves and stand up and say, look, I can be a role model for others. Perhaps that’s why achieving visibility is a long process.They also don’t have the same kind of cultural context and cultural advantage that the trangender community has – because the Hijra and Jogta communities have been culturally visible for so long, they are more recognised than even gay men or lesbians.How have medical practices fed into the shame and stigma that surrounds being intersex, and the idea that it needs to be hidden?One major problem faced by intersex people is sex assignment at birth. If a baby is born intersex and the parents can afford surgery, they immediately try to “correct” the ambiguity by altering the child’s reproductive organs to fit a particular gender.This can be a very problematic thing, because you do not know the gender identity of the child at that point, and you could be doing the wrong operation. And because the genitalia are not mature at that point, it can cause problems later. It also adds to the idea that there is something wrong with being intersex – that it needs to be fixed.

Is there a sense of what percentage of people are born intersex? What makes the intersex community so invisible and underrepresented in the mainstream?Even among the sexual minorities, even compared to trans-men, who get such little attention compared to trans-women, they are a very small number. If you look at a population of intersex people in whose bodies the ambiguity is very clear-cut, they might form 1 in 1,00,000.Being such a small community, there are few people to highlight the issue, to empower themselves and stand up and say, look, I can be a role model for others. Perhaps that’s why achieving visibility is a long process.They also don’t have the same kind of cultural context and cultural advantage that the trangender community has – because the Hijra and Jogta communities have been culturally visible for so long, they are more recognised than even gay men or lesbians.How have medical practices fed into the shame and stigma that surrounds being intersex, and the idea that it needs to be hidden?One major problem faced by intersex people is sex assignment at birth. If a baby is born intersex and the parents can afford surgery, they immediately try to “correct” the ambiguity by altering the child’s reproductive organs to fit a particular gender.This can be a very problematic thing, because you do not know the gender identity of the child at that point, and you could be doing the wrong operation. And because the genitalia are not mature at that point, it can cause problems later. It also adds to the idea that there is something wrong with being intersex – that it needs to be fixed. If you look at medical texts, even today they use terms like “hermaphrodite” or “pseudo-hermaphrodite”. These terms are considered to be degrading, and are denounced by intersex organisations across the world from a human rights perspective. The word that medical practitioners are increasingly using is DSD – Disorders of Sexual Development. Even this is something we do not want, the term ‘disorder’ is something that should be corrected.The terms considered acceptable for use by the intersex community are the terms that we all should be using. In Marathi, this is ‘dwiling’ – which means dual sex, and in English, the sensitive and politically correct term to use is simply, ‘intersex’.A recent order by the Madras High Court banned sex assignment surgery for intersex children, and the Tamil Nadu government has now enforced this as well. How do you see this?It is a good thing, I welcome it, but it has limited application. Parents who want to make their child go through surgery can take them to Karnataka or any other state and do it. We need the Central government to create an Act that stops this.At the moment we are very far away from having such a law. There is no understanding of the term intersex for most of the population, including the media, lawyers, judges, and doctors. Awareness is the first step, and without that there will be no sensitisation. And without sensitisation, people will not understand the injustices that intersex people face, and therefore make changes to fix this.

If you look at medical texts, even today they use terms like “hermaphrodite” or “pseudo-hermaphrodite”. These terms are considered to be degrading, and are denounced by intersex organisations across the world from a human rights perspective. The word that medical practitioners are increasingly using is DSD – Disorders of Sexual Development. Even this is something we do not want, the term ‘disorder’ is something that should be corrected.The terms considered acceptable for use by the intersex community are the terms that we all should be using. In Marathi, this is ‘dwiling’ – which means dual sex, and in English, the sensitive and politically correct term to use is simply, ‘intersex’.A recent order by the Madras High Court banned sex assignment surgery for intersex children, and the Tamil Nadu government has now enforced this as well. How do you see this?It is a good thing, I welcome it, but it has limited application. Parents who want to make their child go through surgery can take them to Karnataka or any other state and do it. We need the Central government to create an Act that stops this.At the moment we are very far away from having such a law. There is no understanding of the term intersex for most of the population, including the media, lawyers, judges, and doctors. Awareness is the first step, and without that there will be no sensitisation. And without sensitisation, people will not understand the injustices that intersex people face, and therefore make changes to fix this. What do you hope that people take away after reading your book, what do you want them to feel?My books on homosexuality, gender identity, my writing in various anthologies, and of course the intersex book all have the same theme – that even though statistically you are a minority, you are not abnormal. You are different from others, but do not feel ashamed of yourself and your sexuality, try to accept yourself, and try to if possible come out to trusted people about your sexuality.Don’t let your sexuality eclipse all other aspects of your life. What happens is that if you focus on and obsess only about sexuality, you are unable to focus on your talent and career and areas you would like to excel in. I want people of sexual minorities to be totally accepting of who they are, be proud of who they are, and show the rest of the world that although you may not accept my variation, I am as good as you and even better at the work I do, and I can challenge you on any and every platform where I feel I can excel and be part of the mainstream. The more we are outside the mainstream, the more we will be marginalised, and the more our rights will be ignored.

What do you hope that people take away after reading your book, what do you want them to feel?My books on homosexuality, gender identity, my writing in various anthologies, and of course the intersex book all have the same theme – that even though statistically you are a minority, you are not abnormal. You are different from others, but do not feel ashamed of yourself and your sexuality, try to accept yourself, and try to if possible come out to trusted people about your sexuality.Don’t let your sexuality eclipse all other aspects of your life. What happens is that if you focus on and obsess only about sexuality, you are unable to focus on your talent and career and areas you would like to excel in. I want people of sexual minorities to be totally accepting of who they are, be proud of who they are, and show the rest of the world that although you may not accept my variation, I am as good as you and even better at the work I do, and I can challenge you on any and every platform where I feel I can excel and be part of the mainstream. The more we are outside the mainstream, the more we will be marginalised, and the more our rights will be ignored. How can we be better allies to the intersex community?I think one way is gaining more knowledge – we need to understand the LGBTI spectrum. We should not use terms that the community sees as derogatory. We need to understand that none of these are disorders or perversions. We are all variations of nature and, there is vast diversity in nature. We should not try to change or alter people just because they are not like us.Yes, surgery is an option if they want to choose it, but in the case of a child, let them grow up to be an adult and decide for themselves whether they would like surgery.Does acknowledging intersex as a biological sex help us break out of the binary of sex as being only male or female? And does it fundamentally change the way we think about sex and gender and society?That is true, not just about anatomical sex, but about gender identity too. Because your gender identity is not binary – it can be male, female, fluid… and it is not determined by the organs in your body. Neither is your sexual orientation determined by anatomy or gender.

How can we be better allies to the intersex community?I think one way is gaining more knowledge – we need to understand the LGBTI spectrum. We should not use terms that the community sees as derogatory. We need to understand that none of these are disorders or perversions. We are all variations of nature and, there is vast diversity in nature. We should not try to change or alter people just because they are not like us.Yes, surgery is an option if they want to choose it, but in the case of a child, let them grow up to be an adult and decide for themselves whether they would like surgery.Does acknowledging intersex as a biological sex help us break out of the binary of sex as being only male or female? And does it fundamentally change the way we think about sex and gender and society?That is true, not just about anatomical sex, but about gender identity too. Because your gender identity is not binary – it can be male, female, fluid… and it is not determined by the organs in your body. Neither is your sexual orientation determined by anatomy or gender. What mindset change is needed to shift the needle on sex assignment surgeries at birth and why should we be rethinking that?The whole idea of sexual minority rights, or LGBTI rights, is to say – My body, my rights, my gender identity, my sexual orientation, and I don't care if others like it or not, I will decide what to do with it.So let the child become an adult, and let them decide whether they want to live as an intersex person or do surgery so their anatomy conforms to their gender identity. All we can do is support them as they are, and say, “We are with you irrespective of your sexual orientation, gender identity or anatomy, we are all human beings.” We must give them the same respect and dignity we give to all our loved ones.Let society not impose its morals on another person, forcing on them something they don’t want.

What mindset change is needed to shift the needle on sex assignment surgeries at birth and why should we be rethinking that?The whole idea of sexual minority rights, or LGBTI rights, is to say – My body, my rights, my gender identity, my sexual orientation, and I don't care if others like it or not, I will decide what to do with it.So let the child become an adult, and let them decide whether they want to live as an intersex person or do surgery so their anatomy conforms to their gender identity. All we can do is support them as they are, and say, “We are with you irrespective of your sexual orientation, gender identity or anatomy, we are all human beings.” We must give them the same respect and dignity we give to all our loved ones.Let society not impose its morals on another person, forcing on them something they don’t want.