I grew up in tents.I wore salwar kameezes that could accommodate a supersize suitcase strapped to me and layered it with dupattas when I was a teenager. If you asked me what colour were those billowing wrappers, I would not be able to tell. If you asked what the texture of the material felt like, were the necks outlined with embroidery, or did the cut resemble an A or V, I would say O. My memories of that time is like a film montage with a me-shaped hole in it. I seem to have taken a magic marker and erased my body painstakingly from every frame. I do not recall my body or my being in it.How do I explain this absence to you? If you ask me to tell you about my life during those times, I could tell you vivid details of every plot and line I encountered in books, how I tussled with certain words and images, and how certain characters still whisper to me. I can tell you about the libraries. Galaxy, the lending library was near the railway station. The owner, a tall, dark man, conjured a perfumed halo. A hint of gold peeped out of his shirt, and he never spoke much to me. I thought he was one of those Alistair Maclean spies who was spending time between missions lazing in this book lined room. I borrowed books in the morning, finished it on my way to junior college in the bus, and in the evening rushed to return them to get the next set. The other library, a vachanalay, which signposted a narrow lane, smelled of agarbattis. The owner’s hair was always oiled; estimates of how many liters of oil were devoted to taming those thick strands makes for fun calculations. He too didn’t speak much, and let me ponder over the shelves. The silence was not what you would call companionable, but that of benign disinterest. On the other hand, if you ask me about the shape of my hips or my breasts when growing up, I don’t know. I never shared a companionable silence with the mirror, and I don’t think the disinterest was benign.I sang. I listened to music. I had the privilege of control over a tape recorder and a ledge by a window where I sat listening to songs late through the night. You couldn’t see much outside the window because it had two layers of mesh – one more closely knit to dissuade pigeons and the other, regular jaali that seemed to invite dust more than dappled sunlight. At home, I wore nighties, that formless fortress of cloth, made usually of some thick durable material. The sides were stained with turmeric, for why use a towel when your sides had ample reams of cloth too.  The tent was comforting. In a way, as my body lived inside that tent, I didn’t need to live inside my body.I think I was afraid of my body. It felt it was always too much of everything. Others had bodies that seemed tame – they did not insist on gaping between buttonholes, they obeyed waistbands, they slid into sleeves, they remained cupped in bras, and they let bones outline them in sharp relief in photographs. My body seemed like a testament to refusal. My breasts pushed through the sides of bracups, tugged on straps, my tummy fought with nadas and waistbands, and button-up jeans, and my arms seemed to resist any sleeve. It felt like constant battle – indented shoulders, branded waists, and abraded thighs – every part seemed to rebel and said no to being tied down, stuffed, or wrapped. And so, to compromise, I loosened up the sartorial shackles. I was afraid I would lose, and my body would take over. Every shoe I would wear would soon develop bestial qualities. Crocodile mouth, I used to call it, for my feet would insist on ripping the seams apart. I remember going to a shoe shop in where a bespectacled Gujarati man clad in creased pants kneeled in front of me, only to laugh at the size of my feet saying, no girl has feet of this size – go anywhere, you won’t get this size, he declared on behalf of shoe manufacturers worldwide. I looked away, unwilling to meet his eyes or my mother’s despairing ones, while he turned to my mother’s dainty size five feet hoping she would want to choose a pair from the tempting array displayed all around. He caught me looking hopefully at a particular row, and smugly said, those are for gents.The world had caliberated, parameterized, and standardized who is a girl, and it had been decided by an august committee that I did not fit the specifications. Though I was told I was a girl, shoes made for girls left half my feet unshod; bras puzzled over spilling flesh; jeans were, well, just not for me. The world screamed, through measurements, labels, and laughter, that my body was illegitimate. But that’s just part of the story.As I was laughing with my friends getting out of a train compartment on the way to a trek, an unknown hand squeezed my left breast. I faltered out of the train, confused and turned, and did not know whose face among the hydra that stared back from the train’s maw owned that hand. My friends had noticed nothing, it was as if the fast receding sensation on my breast was the only sensible remnant.

The tent was comforting. In a way, as my body lived inside that tent, I didn’t need to live inside my body.I think I was afraid of my body. It felt it was always too much of everything. Others had bodies that seemed tame – they did not insist on gaping between buttonholes, they obeyed waistbands, they slid into sleeves, they remained cupped in bras, and they let bones outline them in sharp relief in photographs. My body seemed like a testament to refusal. My breasts pushed through the sides of bracups, tugged on straps, my tummy fought with nadas and waistbands, and button-up jeans, and my arms seemed to resist any sleeve. It felt like constant battle – indented shoulders, branded waists, and abraded thighs – every part seemed to rebel and said no to being tied down, stuffed, or wrapped. And so, to compromise, I loosened up the sartorial shackles. I was afraid I would lose, and my body would take over. Every shoe I would wear would soon develop bestial qualities. Crocodile mouth, I used to call it, for my feet would insist on ripping the seams apart. I remember going to a shoe shop in where a bespectacled Gujarati man clad in creased pants kneeled in front of me, only to laugh at the size of my feet saying, no girl has feet of this size – go anywhere, you won’t get this size, he declared on behalf of shoe manufacturers worldwide. I looked away, unwilling to meet his eyes or my mother’s despairing ones, while he turned to my mother’s dainty size five feet hoping she would want to choose a pair from the tempting array displayed all around. He caught me looking hopefully at a particular row, and smugly said, those are for gents.The world had caliberated, parameterized, and standardized who is a girl, and it had been decided by an august committee that I did not fit the specifications. Though I was told I was a girl, shoes made for girls left half my feet unshod; bras puzzled over spilling flesh; jeans were, well, just not for me. The world screamed, through measurements, labels, and laughter, that my body was illegitimate. But that’s just part of the story.As I was laughing with my friends getting out of a train compartment on the way to a trek, an unknown hand squeezed my left breast. I faltered out of the train, confused and turned, and did not know whose face among the hydra that stared back from the train’s maw owned that hand. My friends had noticed nothing, it was as if the fast receding sensation on my breast was the only sensible remnant.  I am not sure how much I want to recount such momentary violations, for there were many. It was as if, this body of mine, that was deemed illegitimate was still fair game in another murky arena. When my dupatta slid away, the eyes of a senior in college immediately darted to my chest, and he looked away immediately, abashed.Even when I was very young, I understood in an inarticulate way that my body was capable of eliciting desire, but not the wholesome kind that runs cursive in rose day cards, smiling in living room photographs, and is given a U certificate. Bodies like mine, it was indicated in several different, deliberate ways, were suited for a different kind of desire – one that was between sheets, either on the bed or in a magazine. And in a world spun into a digital web, this other kind of desire was the lifeblood of its most profitable industry, porn. And so, the word best suited to my body was not just illegitimate, it was also illicit.Many years passed. I was once telling a long-haired friend who was telling me about her boy troubles that oh, ok, it is not something I know too well about. Why, she asked. Well, I began, faltered, and blurted, am not pretty, so boys never liked me that way. She stared at me awhile. And said, I think you are confusing beautiful with sexy. We spoke of other things, but over the next few weeks, months, years, and decades, her words kept coming back to me. I may not squeeze into the world’s mould labeled beauty, but did that mean that I was not desirable? Some more years passed.Recently, I came across a project called ‘Identitty’, where an artist Indu Harikumar was exploring the relationship women share with their breasts. People shared their stories, and sent a photograph of their breasts to her – and she drew them. She had stopped accepting contributions. The prompt called out to me – I wanted to write about what I felt about my breasts, and before I knew it, I had typed out a few pages. I sent it to her, thanking her for the project, for it did feel like I had dislodged something within me.She wrote back. Asked me for a picture. I was petrified. I had just written about that girl who lived in tents, and suddenly I was back being that girl who tugged on her kameezzes, wishing for that tent. I had two choices – I could retreat into that tent, or. Before I could change my mind, I went to my room, shut the doors and windows, and took my top off. Turning the camera toward me with no clothes on, felt like deciding to go buy groceries, naked – utterly demented and prosaic, all at the same time. I remember laughing, loudly, almost startling myself. I could go and read the fourteenth finance commission report and forget all about this escapade. What if someone stole my phone, and made billboards of my boobs. Suppose my phone slipped from my hands while chatting with my mother and in trying to catch the phone, I pressed something and sent these to my mother? It was as if, faced with that unbearable lightness of a selfie, I felt a bit foolish, and that made it all alright. I clicked. Clicked some more.Some months passed.I was lying on my bed chatting with someone. I finished and then was just fiddling with the camera. I tried to take a selfie, felt conscious. And then dipped the camera lower. I unbuttoned. I clicked. This time, I did not think so much.As I scroll through those images of my naked body, it is as if I am able to gaze upon myself, without looking back at myself, as a mirror is wont to do. I take my time, linger on my folds, the way the skin gleams, the way it colours differently in different places. Often, I can’t shoot my face with the picture, and so, I become anonymous – I don’t know whose body it is. It feels delicious, just watching the skin, the way sometimes body hair curls, and I feel compelled to touch.

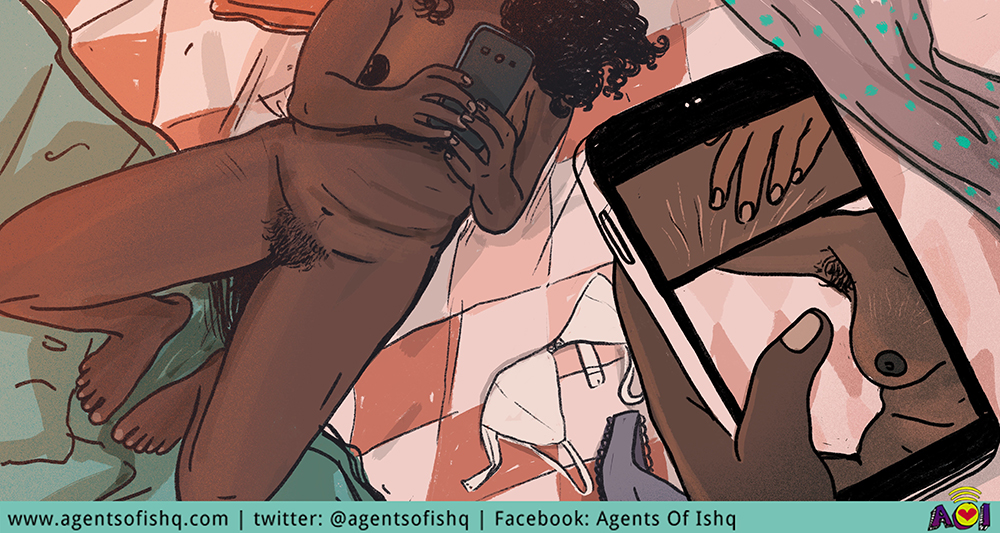

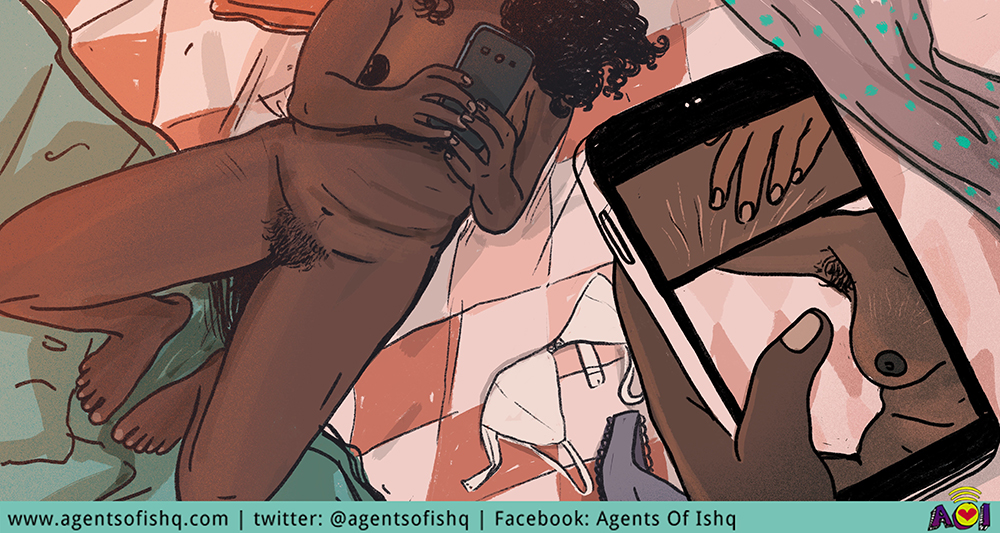

I am not sure how much I want to recount such momentary violations, for there were many. It was as if, this body of mine, that was deemed illegitimate was still fair game in another murky arena. When my dupatta slid away, the eyes of a senior in college immediately darted to my chest, and he looked away immediately, abashed.Even when I was very young, I understood in an inarticulate way that my body was capable of eliciting desire, but not the wholesome kind that runs cursive in rose day cards, smiling in living room photographs, and is given a U certificate. Bodies like mine, it was indicated in several different, deliberate ways, were suited for a different kind of desire – one that was between sheets, either on the bed or in a magazine. And in a world spun into a digital web, this other kind of desire was the lifeblood of its most profitable industry, porn. And so, the word best suited to my body was not just illegitimate, it was also illicit.Many years passed. I was once telling a long-haired friend who was telling me about her boy troubles that oh, ok, it is not something I know too well about. Why, she asked. Well, I began, faltered, and blurted, am not pretty, so boys never liked me that way. She stared at me awhile. And said, I think you are confusing beautiful with sexy. We spoke of other things, but over the next few weeks, months, years, and decades, her words kept coming back to me. I may not squeeze into the world’s mould labeled beauty, but did that mean that I was not desirable? Some more years passed.Recently, I came across a project called ‘Identitty’, where an artist Indu Harikumar was exploring the relationship women share with their breasts. People shared their stories, and sent a photograph of their breasts to her – and she drew them. She had stopped accepting contributions. The prompt called out to me – I wanted to write about what I felt about my breasts, and before I knew it, I had typed out a few pages. I sent it to her, thanking her for the project, for it did feel like I had dislodged something within me.She wrote back. Asked me for a picture. I was petrified. I had just written about that girl who lived in tents, and suddenly I was back being that girl who tugged on her kameezzes, wishing for that tent. I had two choices – I could retreat into that tent, or. Before I could change my mind, I went to my room, shut the doors and windows, and took my top off. Turning the camera toward me with no clothes on, felt like deciding to go buy groceries, naked – utterly demented and prosaic, all at the same time. I remember laughing, loudly, almost startling myself. I could go and read the fourteenth finance commission report and forget all about this escapade. What if someone stole my phone, and made billboards of my boobs. Suppose my phone slipped from my hands while chatting with my mother and in trying to catch the phone, I pressed something and sent these to my mother? It was as if, faced with that unbearable lightness of a selfie, I felt a bit foolish, and that made it all alright. I clicked. Clicked some more.Some months passed.I was lying on my bed chatting with someone. I finished and then was just fiddling with the camera. I tried to take a selfie, felt conscious. And then dipped the camera lower. I unbuttoned. I clicked. This time, I did not think so much.As I scroll through those images of my naked body, it is as if I am able to gaze upon myself, without looking back at myself, as a mirror is wont to do. I take my time, linger on my folds, the way the skin gleams, the way it colours differently in different places. Often, I can’t shoot my face with the picture, and so, I become anonymous – I don’t know whose body it is. It feels delicious, just watching the skin, the way sometimes body hair curls, and I feel compelled to touch.  Somehow, I was able to distance myself from my own body. It is objectification, of course, but perhaps, in being both the person doing the objectification and being objectified, it felt safe. I wondered about how I framed these photographs – was I drawing from a vocabulary that objectified women? Did I want to be seen a certain way? I tried to shoot myself in postures, which would be usually deemed unflattering, but even then, watching those photographs, I discovered a new kind of desire, a desire that slowly cut that invisible cord tying it to beauty.As I walked on roads, I watched people, and thought, naked, all of us have different shapes, and these are desirable shapes. I would like to touch an arm, slide my hand over someone’s belly, kiss chubby thighs, or stroke bony hips. I sometimes just let my hands slide over my naked body, closing my eyes, and feel skin meet skin, a warmth that speaks of life. It feels like desire, and I do not need to even see myself then. Beauty is about seeing, desire is about touch and want. After bathing, as I rub myself with a towel, I linger here and there, and wonder how the skin of different parts feels so differently. I look at pockmarks, darkened patches, stretches, and gently trace a finger over them, and it just feels like skin. All these years, I had thought my body was something I had to battle with. And here I was, suddenly wanting to rub myself, massage my legs, bite my own tummy, and smell my palm as it wandered over my face.I met a friend, and over conversation I told her about taking these photographs. She wanted to see. I gave her the phone, and she glanced here and there, and then looked. I watched her face, and something in me unfurled. It was no more my secret, someone else had seen it, seen my body, the one I live in, and we giggled together. Ini is 39. During lockdown Ini realised that you cannot tickle yourself.

Somehow, I was able to distance myself from my own body. It is objectification, of course, but perhaps, in being both the person doing the objectification and being objectified, it felt safe. I wondered about how I framed these photographs – was I drawing from a vocabulary that objectified women? Did I want to be seen a certain way? I tried to shoot myself in postures, which would be usually deemed unflattering, but even then, watching those photographs, I discovered a new kind of desire, a desire that slowly cut that invisible cord tying it to beauty.As I walked on roads, I watched people, and thought, naked, all of us have different shapes, and these are desirable shapes. I would like to touch an arm, slide my hand over someone’s belly, kiss chubby thighs, or stroke bony hips. I sometimes just let my hands slide over my naked body, closing my eyes, and feel skin meet skin, a warmth that speaks of life. It feels like desire, and I do not need to even see myself then. Beauty is about seeing, desire is about touch and want. After bathing, as I rub myself with a towel, I linger here and there, and wonder how the skin of different parts feels so differently. I look at pockmarks, darkened patches, stretches, and gently trace a finger over them, and it just feels like skin. All these years, I had thought my body was something I had to battle with. And here I was, suddenly wanting to rub myself, massage my legs, bite my own tummy, and smell my palm as it wandered over my face.I met a friend, and over conversation I told her about taking these photographs. She wanted to see. I gave her the phone, and she glanced here and there, and then looked. I watched her face, and something in me unfurled. It was no more my secret, someone else had seen it, seen my body, the one I live in, and we giggled together. Ini is 39. During lockdown Ini realised that you cannot tickle yourself.

The tent was comforting. In a way, as my body lived inside that tent, I didn’t need to live inside my body.I think I was afraid of my body. It felt it was always too much of everything. Others had bodies that seemed tame – they did not insist on gaping between buttonholes, they obeyed waistbands, they slid into sleeves, they remained cupped in bras, and they let bones outline them in sharp relief in photographs. My body seemed like a testament to refusal. My breasts pushed through the sides of bracups, tugged on straps, my tummy fought with nadas and waistbands, and button-up jeans, and my arms seemed to resist any sleeve. It felt like constant battle – indented shoulders, branded waists, and abraded thighs – every part seemed to rebel and said no to being tied down, stuffed, or wrapped. And so, to compromise, I loosened up the sartorial shackles. I was afraid I would lose, and my body would take over. Every shoe I would wear would soon develop bestial qualities. Crocodile mouth, I used to call it, for my feet would insist on ripping the seams apart. I remember going to a shoe shop in where a bespectacled Gujarati man clad in creased pants kneeled in front of me, only to laugh at the size of my feet saying, no girl has feet of this size – go anywhere, you won’t get this size, he declared on behalf of shoe manufacturers worldwide. I looked away, unwilling to meet his eyes or my mother’s despairing ones, while he turned to my mother’s dainty size five feet hoping she would want to choose a pair from the tempting array displayed all around. He caught me looking hopefully at a particular row, and smugly said, those are for gents.The world had caliberated, parameterized, and standardized who is a girl, and it had been decided by an august committee that I did not fit the specifications. Though I was told I was a girl, shoes made for girls left half my feet unshod; bras puzzled over spilling flesh; jeans were, well, just not for me. The world screamed, through measurements, labels, and laughter, that my body was illegitimate. But that’s just part of the story.As I was laughing with my friends getting out of a train compartment on the way to a trek, an unknown hand squeezed my left breast. I faltered out of the train, confused and turned, and did not know whose face among the hydra that stared back from the train’s maw owned that hand. My friends had noticed nothing, it was as if the fast receding sensation on my breast was the only sensible remnant.

The tent was comforting. In a way, as my body lived inside that tent, I didn’t need to live inside my body.I think I was afraid of my body. It felt it was always too much of everything. Others had bodies that seemed tame – they did not insist on gaping between buttonholes, they obeyed waistbands, they slid into sleeves, they remained cupped in bras, and they let bones outline them in sharp relief in photographs. My body seemed like a testament to refusal. My breasts pushed through the sides of bracups, tugged on straps, my tummy fought with nadas and waistbands, and button-up jeans, and my arms seemed to resist any sleeve. It felt like constant battle – indented shoulders, branded waists, and abraded thighs – every part seemed to rebel and said no to being tied down, stuffed, or wrapped. And so, to compromise, I loosened up the sartorial shackles. I was afraid I would lose, and my body would take over. Every shoe I would wear would soon develop bestial qualities. Crocodile mouth, I used to call it, for my feet would insist on ripping the seams apart. I remember going to a shoe shop in where a bespectacled Gujarati man clad in creased pants kneeled in front of me, only to laugh at the size of my feet saying, no girl has feet of this size – go anywhere, you won’t get this size, he declared on behalf of shoe manufacturers worldwide. I looked away, unwilling to meet his eyes or my mother’s despairing ones, while he turned to my mother’s dainty size five feet hoping she would want to choose a pair from the tempting array displayed all around. He caught me looking hopefully at a particular row, and smugly said, those are for gents.The world had caliberated, parameterized, and standardized who is a girl, and it had been decided by an august committee that I did not fit the specifications. Though I was told I was a girl, shoes made for girls left half my feet unshod; bras puzzled over spilling flesh; jeans were, well, just not for me. The world screamed, through measurements, labels, and laughter, that my body was illegitimate. But that’s just part of the story.As I was laughing with my friends getting out of a train compartment on the way to a trek, an unknown hand squeezed my left breast. I faltered out of the train, confused and turned, and did not know whose face among the hydra that stared back from the train’s maw owned that hand. My friends had noticed nothing, it was as if the fast receding sensation on my breast was the only sensible remnant.  I am not sure how much I want to recount such momentary violations, for there were many. It was as if, this body of mine, that was deemed illegitimate was still fair game in another murky arena. When my dupatta slid away, the eyes of a senior in college immediately darted to my chest, and he looked away immediately, abashed.Even when I was very young, I understood in an inarticulate way that my body was capable of eliciting desire, but not the wholesome kind that runs cursive in rose day cards, smiling in living room photographs, and is given a U certificate. Bodies like mine, it was indicated in several different, deliberate ways, were suited for a different kind of desire – one that was between sheets, either on the bed or in a magazine. And in a world spun into a digital web, this other kind of desire was the lifeblood of its most profitable industry, porn. And so, the word best suited to my body was not just illegitimate, it was also illicit.Many years passed. I was once telling a long-haired friend who was telling me about her boy troubles that oh, ok, it is not something I know too well about. Why, she asked. Well, I began, faltered, and blurted, am not pretty, so boys never liked me that way. She stared at me awhile. And said, I think you are confusing beautiful with sexy. We spoke of other things, but over the next few weeks, months, years, and decades, her words kept coming back to me. I may not squeeze into the world’s mould labeled beauty, but did that mean that I was not desirable? Some more years passed.Recently, I came across a project called ‘Identitty’, where an artist Indu Harikumar was exploring the relationship women share with their breasts. People shared their stories, and sent a photograph of their breasts to her – and she drew them. She had stopped accepting contributions. The prompt called out to me – I wanted to write about what I felt about my breasts, and before I knew it, I had typed out a few pages. I sent it to her, thanking her for the project, for it did feel like I had dislodged something within me.She wrote back. Asked me for a picture. I was petrified. I had just written about that girl who lived in tents, and suddenly I was back being that girl who tugged on her kameezzes, wishing for that tent. I had two choices – I could retreat into that tent, or. Before I could change my mind, I went to my room, shut the doors and windows, and took my top off. Turning the camera toward me with no clothes on, felt like deciding to go buy groceries, naked – utterly demented and prosaic, all at the same time. I remember laughing, loudly, almost startling myself. I could go and read the fourteenth finance commission report and forget all about this escapade. What if someone stole my phone, and made billboards of my boobs. Suppose my phone slipped from my hands while chatting with my mother and in trying to catch the phone, I pressed something and sent these to my mother? It was as if, faced with that unbearable lightness of a selfie, I felt a bit foolish, and that made it all alright. I clicked. Clicked some more.Some months passed.I was lying on my bed chatting with someone. I finished and then was just fiddling with the camera. I tried to take a selfie, felt conscious. And then dipped the camera lower. I unbuttoned. I clicked. This time, I did not think so much.As I scroll through those images of my naked body, it is as if I am able to gaze upon myself, without looking back at myself, as a mirror is wont to do. I take my time, linger on my folds, the way the skin gleams, the way it colours differently in different places. Often, I can’t shoot my face with the picture, and so, I become anonymous – I don’t know whose body it is. It feels delicious, just watching the skin, the way sometimes body hair curls, and I feel compelled to touch.

I am not sure how much I want to recount such momentary violations, for there were many. It was as if, this body of mine, that was deemed illegitimate was still fair game in another murky arena. When my dupatta slid away, the eyes of a senior in college immediately darted to my chest, and he looked away immediately, abashed.Even when I was very young, I understood in an inarticulate way that my body was capable of eliciting desire, but not the wholesome kind that runs cursive in rose day cards, smiling in living room photographs, and is given a U certificate. Bodies like mine, it was indicated in several different, deliberate ways, were suited for a different kind of desire – one that was between sheets, either on the bed or in a magazine. And in a world spun into a digital web, this other kind of desire was the lifeblood of its most profitable industry, porn. And so, the word best suited to my body was not just illegitimate, it was also illicit.Many years passed. I was once telling a long-haired friend who was telling me about her boy troubles that oh, ok, it is not something I know too well about. Why, she asked. Well, I began, faltered, and blurted, am not pretty, so boys never liked me that way. She stared at me awhile. And said, I think you are confusing beautiful with sexy. We spoke of other things, but over the next few weeks, months, years, and decades, her words kept coming back to me. I may not squeeze into the world’s mould labeled beauty, but did that mean that I was not desirable? Some more years passed.Recently, I came across a project called ‘Identitty’, where an artist Indu Harikumar was exploring the relationship women share with their breasts. People shared their stories, and sent a photograph of their breasts to her – and she drew them. She had stopped accepting contributions. The prompt called out to me – I wanted to write about what I felt about my breasts, and before I knew it, I had typed out a few pages. I sent it to her, thanking her for the project, for it did feel like I had dislodged something within me.She wrote back. Asked me for a picture. I was petrified. I had just written about that girl who lived in tents, and suddenly I was back being that girl who tugged on her kameezzes, wishing for that tent. I had two choices – I could retreat into that tent, or. Before I could change my mind, I went to my room, shut the doors and windows, and took my top off. Turning the camera toward me with no clothes on, felt like deciding to go buy groceries, naked – utterly demented and prosaic, all at the same time. I remember laughing, loudly, almost startling myself. I could go and read the fourteenth finance commission report and forget all about this escapade. What if someone stole my phone, and made billboards of my boobs. Suppose my phone slipped from my hands while chatting with my mother and in trying to catch the phone, I pressed something and sent these to my mother? It was as if, faced with that unbearable lightness of a selfie, I felt a bit foolish, and that made it all alright. I clicked. Clicked some more.Some months passed.I was lying on my bed chatting with someone. I finished and then was just fiddling with the camera. I tried to take a selfie, felt conscious. And then dipped the camera lower. I unbuttoned. I clicked. This time, I did not think so much.As I scroll through those images of my naked body, it is as if I am able to gaze upon myself, without looking back at myself, as a mirror is wont to do. I take my time, linger on my folds, the way the skin gleams, the way it colours differently in different places. Often, I can’t shoot my face with the picture, and so, I become anonymous – I don’t know whose body it is. It feels delicious, just watching the skin, the way sometimes body hair curls, and I feel compelled to touch.  Somehow, I was able to distance myself from my own body. It is objectification, of course, but perhaps, in being both the person doing the objectification and being objectified, it felt safe. I wondered about how I framed these photographs – was I drawing from a vocabulary that objectified women? Did I want to be seen a certain way? I tried to shoot myself in postures, which would be usually deemed unflattering, but even then, watching those photographs, I discovered a new kind of desire, a desire that slowly cut that invisible cord tying it to beauty.As I walked on roads, I watched people, and thought, naked, all of us have different shapes, and these are desirable shapes. I would like to touch an arm, slide my hand over someone’s belly, kiss chubby thighs, or stroke bony hips. I sometimes just let my hands slide over my naked body, closing my eyes, and feel skin meet skin, a warmth that speaks of life. It feels like desire, and I do not need to even see myself then. Beauty is about seeing, desire is about touch and want. After bathing, as I rub myself with a towel, I linger here and there, and wonder how the skin of different parts feels so differently. I look at pockmarks, darkened patches, stretches, and gently trace a finger over them, and it just feels like skin. All these years, I had thought my body was something I had to battle with. And here I was, suddenly wanting to rub myself, massage my legs, bite my own tummy, and smell my palm as it wandered over my face.I met a friend, and over conversation I told her about taking these photographs. She wanted to see. I gave her the phone, and she glanced here and there, and then looked. I watched her face, and something in me unfurled. It was no more my secret, someone else had seen it, seen my body, the one I live in, and we giggled together. Ini is 39. During lockdown Ini realised that you cannot tickle yourself.

Somehow, I was able to distance myself from my own body. It is objectification, of course, but perhaps, in being both the person doing the objectification and being objectified, it felt safe. I wondered about how I framed these photographs – was I drawing from a vocabulary that objectified women? Did I want to be seen a certain way? I tried to shoot myself in postures, which would be usually deemed unflattering, but even then, watching those photographs, I discovered a new kind of desire, a desire that slowly cut that invisible cord tying it to beauty.As I walked on roads, I watched people, and thought, naked, all of us have different shapes, and these are desirable shapes. I would like to touch an arm, slide my hand over someone’s belly, kiss chubby thighs, or stroke bony hips. I sometimes just let my hands slide over my naked body, closing my eyes, and feel skin meet skin, a warmth that speaks of life. It feels like desire, and I do not need to even see myself then. Beauty is about seeing, desire is about touch and want. After bathing, as I rub myself with a towel, I linger here and there, and wonder how the skin of different parts feels so differently. I look at pockmarks, darkened patches, stretches, and gently trace a finger over them, and it just feels like skin. All these years, I had thought my body was something I had to battle with. And here I was, suddenly wanting to rub myself, massage my legs, bite my own tummy, and smell my palm as it wandered over my face.I met a friend, and over conversation I told her about taking these photographs. She wanted to see. I gave her the phone, and she glanced here and there, and then looked. I watched her face, and something in me unfurled. It was no more my secret, someone else had seen it, seen my body, the one I live in, and we giggled together. Ini is 39. During lockdown Ini realised that you cannot tickle yourself.