‘Not because I have wisdom, but because I care’: An Interview with Suniti Namjoshi

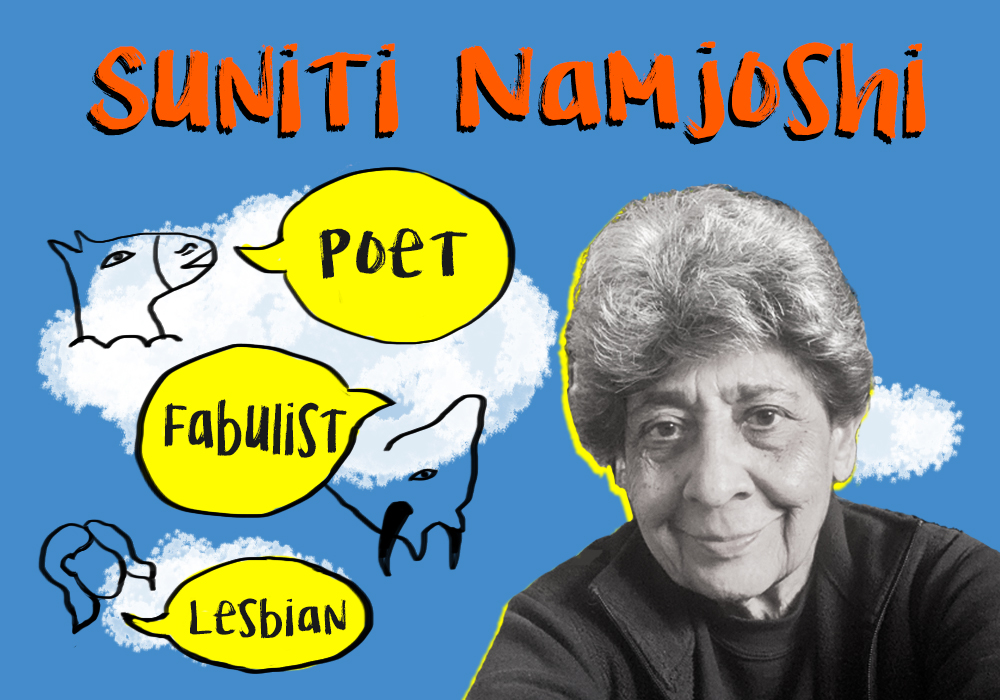

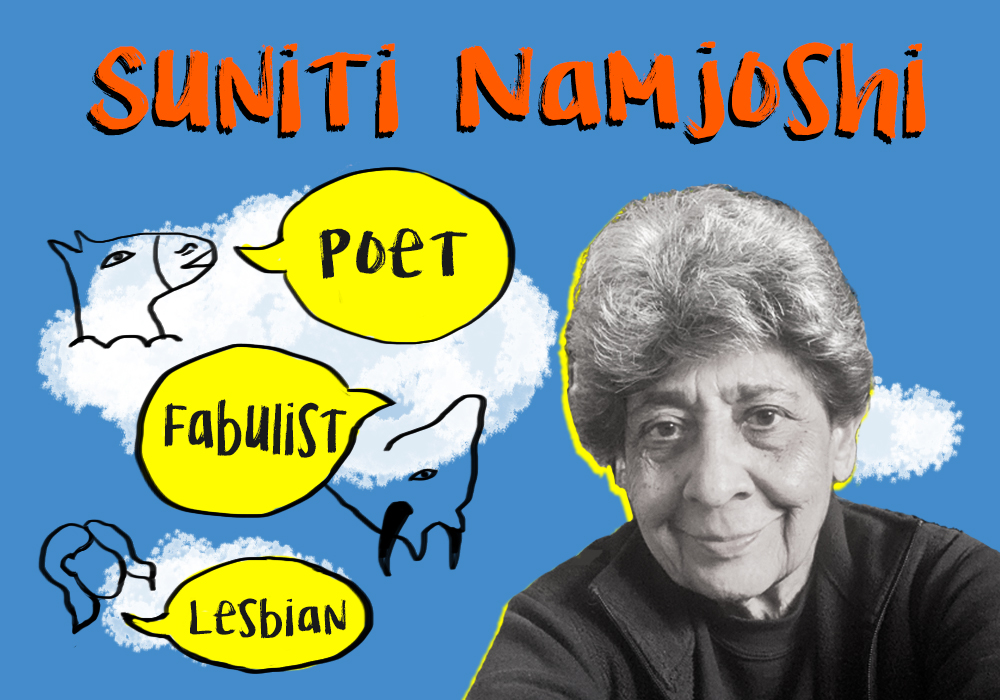

Poet, fabulist, lesbian - She tells AOI about her journey as a writer, lover & person!

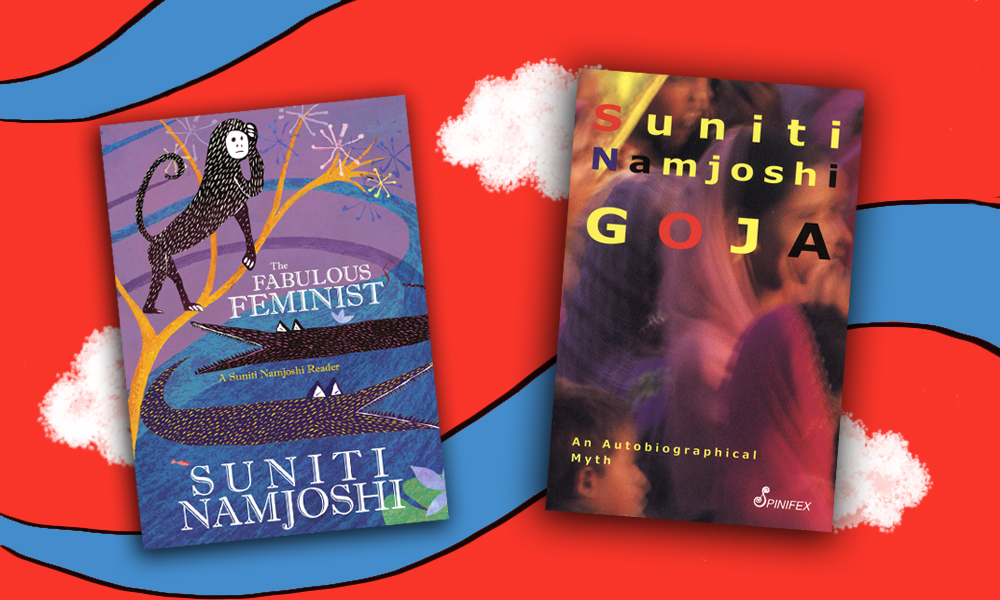

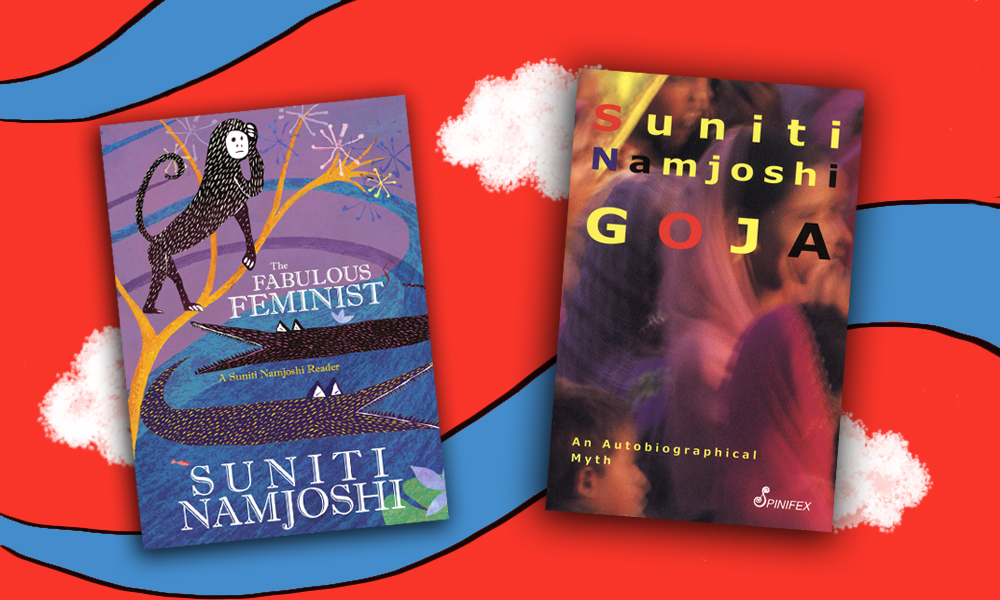

Suniti Namjoshi was born in 1941, served in the IAS for a while, and wrote Feminist Fables in 1981. She is a novelist, fabulist, poet, lesbian, feminist and one of the warmest, wisest, funniest voices to come out of India. If you read one of her books – say, Conversations with Cow, The Blue Donkey Fables, The Mothers of Maya Diip, Goja: An Autobiographical Myth, Saint Suniti and the Dragon and many others, you will laugh out loud and say Yes! Exactly! even if you are alone in the room.. If you’ve been part of groups and organisations, you will recognize many #BoreMatKarYaar types pompous behaviours and rigid positions, and feel amused and relieved that you can make fun of that with affection, and without ever mocking or denouncing individuals or betraying political ideals. There is intimacy and there is distance and they dance together in her pithy fables, fertile poems and tart lines.Her work is deeply political because it is deeply pleasurable, and completely free of ideological orthodoxy. It is also so Indian because it doesn’t try to be, but it has that karara sarcasm we know from so many Indian languages. It searches for the heart of fairness and freedom with mischief, irony, marvelous animal characters, unique lady people and beautiful sentences. A tasting menu of her work is to be found in The Fabulous Feminist: A Suniti Namjoshi Reader, published by Zubaan, so go do some gourmet overeating. She spoke to Agents of Ishq about her writing choices – why she chooses to work with fables for instance – what her lesbian identity means for her life and work, and her journey as a writer, a lover and a person.Yes, we did ask her “what is love?”. And yes, she did answer. So, read on.

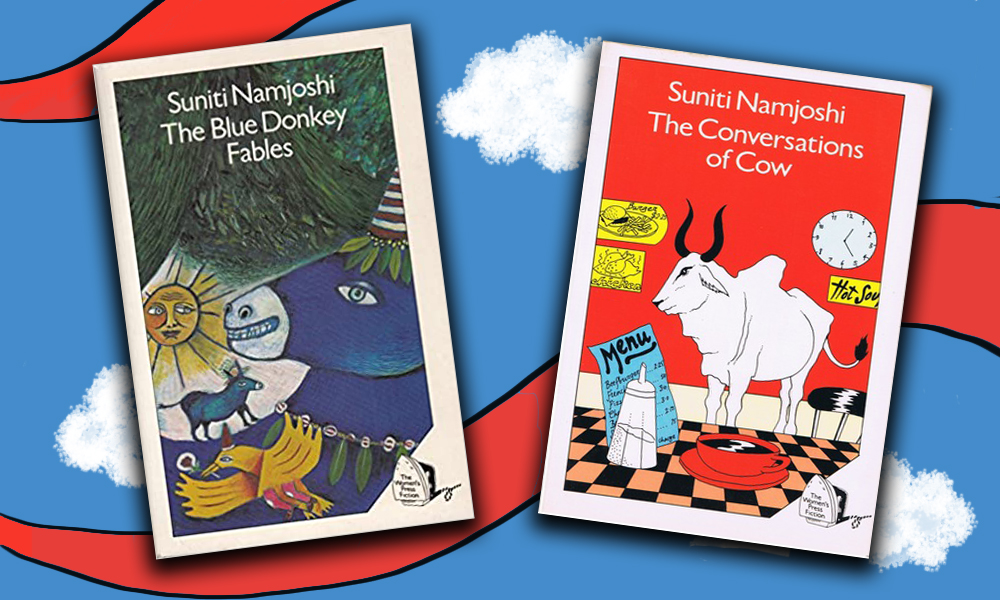

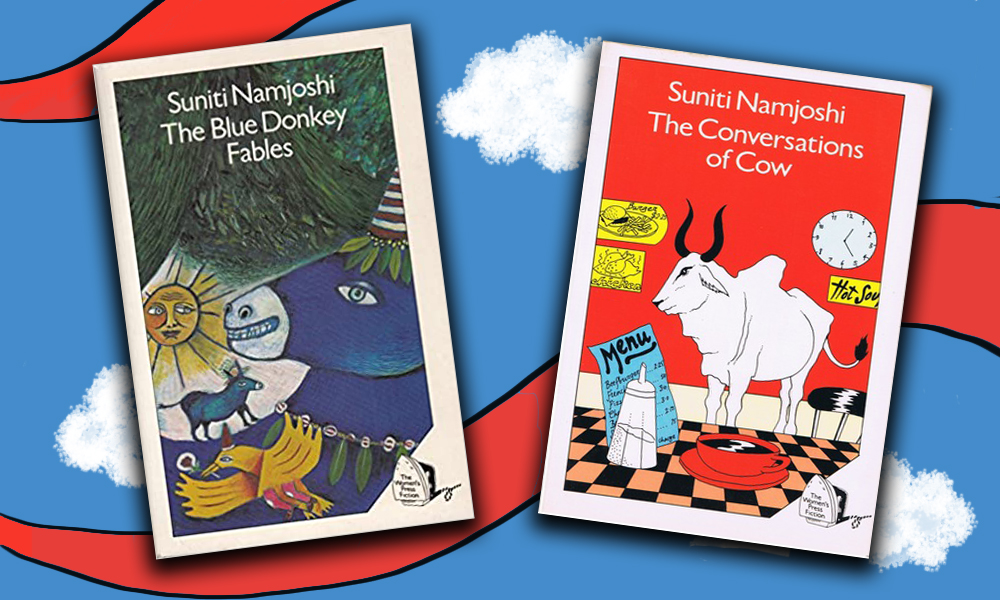

Suniti Namjoshi was born in 1941, served in the IAS for a while, and wrote Feminist Fables in 1981. She is a novelist, fabulist, poet, lesbian, feminist and one of the warmest, wisest, funniest voices to come out of India. If you read one of her books – say, Conversations with Cow, The Blue Donkey Fables, The Mothers of Maya Diip, Goja: An Autobiographical Myth, Saint Suniti and the Dragon and many others, you will laugh out loud and say Yes! Exactly! even if you are alone in the room.. If you’ve been part of groups and organisations, you will recognize many #BoreMatKarYaar types pompous behaviours and rigid positions, and feel amused and relieved that you can make fun of that with affection, and without ever mocking or denouncing individuals or betraying political ideals. There is intimacy and there is distance and they dance together in her pithy fables, fertile poems and tart lines.Her work is deeply political because it is deeply pleasurable, and completely free of ideological orthodoxy. It is also so Indian because it doesn’t try to be, but it has that karara sarcasm we know from so many Indian languages. It searches for the heart of fairness and freedom with mischief, irony, marvelous animal characters, unique lady people and beautiful sentences. A tasting menu of her work is to be found in The Fabulous Feminist: A Suniti Namjoshi Reader, published by Zubaan, so go do some gourmet overeating. She spoke to Agents of Ishq about her writing choices – why she chooses to work with fables for instance – what her lesbian identity means for her life and work, and her journey as a writer, a lover and a person.Yes, we did ask her “what is love?”. And yes, she did answer. So, read on.  The Blue Donkey Fables and then The Conversations of Cow have a thrilling interplay – there is the economy of form, which is so precise, and whimsical humour, which feels almost casually plentiful. What do you want to bring alive for the reader with this combination?Being told that is thrilling for me too – for any writer probably! A lot of hard work goes into the writing and then there’s the necessary ten percent of luck or inspiration. I want my work to produce a feeling of strength from its clarity and of joy from the way it all works together. Searching for you online sometimes finds you described as a lesbian writer. How do you relate to that description?Well, that was what I took on when I decided it was necessary to come out and say to people that I and other lesbians by implication are human – one nose , two eyes etc.

The Blue Donkey Fables and then The Conversations of Cow have a thrilling interplay – there is the economy of form, which is so precise, and whimsical humour, which feels almost casually plentiful. What do you want to bring alive for the reader with this combination?Being told that is thrilling for me too – for any writer probably! A lot of hard work goes into the writing and then there’s the necessary ten percent of luck or inspiration. I want my work to produce a feeling of strength from its clarity and of joy from the way it all works together. Searching for you online sometimes finds you described as a lesbian writer. How do you relate to that description?Well, that was what I took on when I decided it was necessary to come out and say to people that I and other lesbians by implication are human – one nose , two eyes etc.  You use poetry, fable, autobiographical myth and so on over more commonly found realist political forms, while talking about identity, sexuality and the dynamics between groups and people. Do you think of your work as political? In what way would you describe its political-ness?I haven’t chosen these forms consciously. By temperament all I want to do is try to write a good poem or a good fable and hide behind a book. I didn’t want to engage in lesbian feminist politics. I did so, because I realized that other people, especially my friend and ex-partner Christine Donald aka Hilary Clare, were fighting my battles for me. It wouldn’t have been fair just to sit back. I also realized that politics has something to do with ethics. Luckily for me the fable, which is a form that comes easily to me, is a didactic form. I don’t necessarily want to tell people what to think, but I do want them to think.

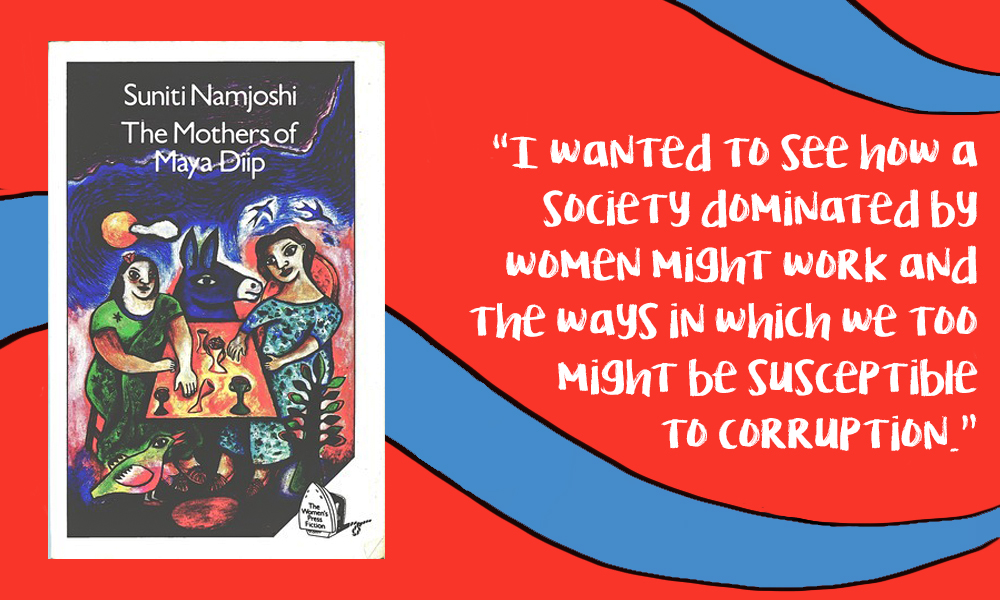

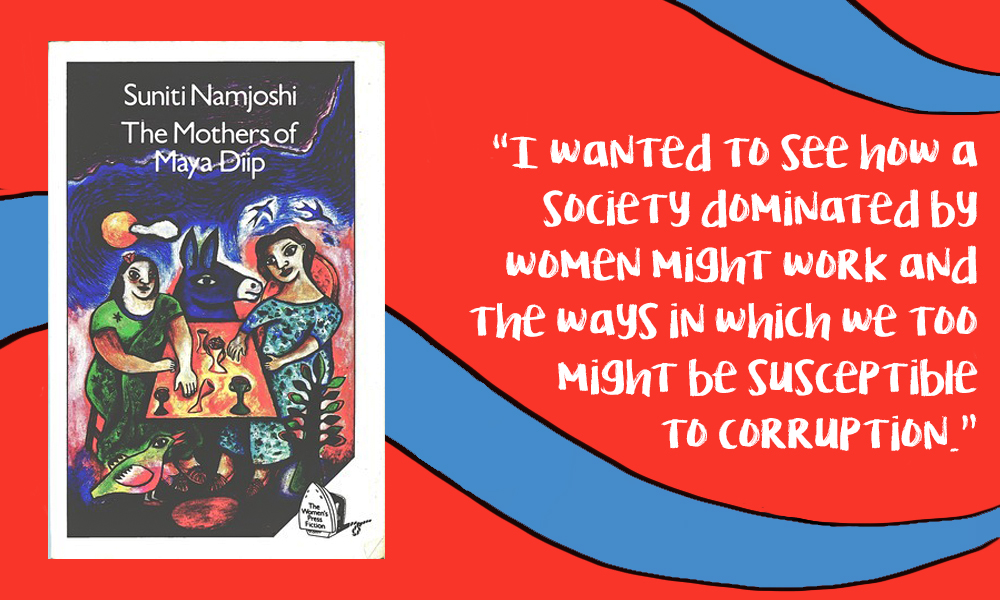

You use poetry, fable, autobiographical myth and so on over more commonly found realist political forms, while talking about identity, sexuality and the dynamics between groups and people. Do you think of your work as political? In what way would you describe its political-ness?I haven’t chosen these forms consciously. By temperament all I want to do is try to write a good poem or a good fable and hide behind a book. I didn’t want to engage in lesbian feminist politics. I did so, because I realized that other people, especially my friend and ex-partner Christine Donald aka Hilary Clare, were fighting my battles for me. It wouldn’t have been fair just to sit back. I also realized that politics has something to do with ethics. Luckily for me the fable, which is a form that comes easily to me, is a didactic form. I don’t necessarily want to tell people what to think, but I do want them to think.  Your book The Mothers of Maya Diip, is a dystopian novel in which a matriarchy prevails. It seems to question utopia, without negating a search for the utopian. What fuelled this book and the way it is written?Protesting against oppression makes us feel that we are in the right. But we are only right in that particular respect. As women, as human beings, we have to question ourselves as well. I wanted to see how a society dominated by women might work and the ways in which we too might be susceptible to corruption. I also wanted to demonstrate how the ‘norms’ in a society - however bizarre - govern interactions. The search for the utopian has to be an ongoing quest perhaps as perfection would be static.

Your book The Mothers of Maya Diip, is a dystopian novel in which a matriarchy prevails. It seems to question utopia, without negating a search for the utopian. What fuelled this book and the way it is written?Protesting against oppression makes us feel that we are in the right. But we are only right in that particular respect. As women, as human beings, we have to question ourselves as well. I wanted to see how a society dominated by women might work and the ways in which we too might be susceptible to corruption. I also wanted to demonstrate how the ‘norms’ in a society - however bizarre - govern interactions. The search for the utopian has to be an ongoing quest perhaps as perfection would be static.  One way of reading The Conversations of Cow is to see it as a relationship story and also a little bit of a coming out to/with yourself kind of story. Why do you think you never wanted to talk about these experiences in a straightforward direct way?It wasn’t intended as a coming out story. I was part of the lesbian feminist movement in Canada and later in Britain, but I did want to question some aspects of the party line without undermining the movement. That’s why I chose my own name for the central character. Suniti gets into all sorts of trouble coping with gender stereotyping, problems of identity and her own preconceptions. I have said something about my own experience in a more straightforward way in the introductions to the different sections of The Fabulous Feminist (Zubaan, 2012). The book contains excerpts from several of my books and explains the context in which I came to write a particular work. And Goja is, after all, an autobiographical myth. Saying something outright is not necessarily a more accurate version of experience, though it can be devastating. That too is part of the craft. The form I choose depends on what I’m trying to do. And also I have to be able to use the form.

One way of reading The Conversations of Cow is to see it as a relationship story and also a little bit of a coming out to/with yourself kind of story. Why do you think you never wanted to talk about these experiences in a straightforward direct way?It wasn’t intended as a coming out story. I was part of the lesbian feminist movement in Canada and later in Britain, but I did want to question some aspects of the party line without undermining the movement. That’s why I chose my own name for the central character. Suniti gets into all sorts of trouble coping with gender stereotyping, problems of identity and her own preconceptions. I have said something about my own experience in a more straightforward way in the introductions to the different sections of The Fabulous Feminist (Zubaan, 2012). The book contains excerpts from several of my books and explains the context in which I came to write a particular work. And Goja is, after all, an autobiographical myth. Saying something outright is not necessarily a more accurate version of experience, though it can be devastating. That too is part of the craft. The form I choose depends on what I’m trying to do. And also I have to be able to use the form.  Your books often feature a character called Suniti. She isn’t the same character, though she does have similar characteristics of being very sincere and sometimes nonplussed by events, like the straight man in old comedies. Why does Suniti appear in this way?I use the ‘Suniti’ name in different ways in different books. In The Conversations of Cow it allows me to soften the satire against a well meaning lesbian feminist. It also allows me to bring in the Indian background with just one word, and without muddying the narrative with a lengthy explanation. And in Saint Suniti and the Dragon it allows me to depict the three locations of her struggle to be good: within her psyche, within the text, and in the ‘real’ world.

Your books often feature a character called Suniti. She isn’t the same character, though she does have similar characteristics of being very sincere and sometimes nonplussed by events, like the straight man in old comedies. Why does Suniti appear in this way?I use the ‘Suniti’ name in different ways in different books. In The Conversations of Cow it allows me to soften the satire against a well meaning lesbian feminist. It also allows me to bring in the Indian background with just one word, and without muddying the narrative with a lengthy explanation. And in Saint Suniti and the Dragon it allows me to depict the three locations of her struggle to be good: within her psyche, within the text, and in the ‘real’ world.  You come from a generation in India where hardly anyone was public and out as queer/lesbian. How did that journey happen for you? How did being a writer and diverse social responses to being lesbian shape that journey?It was difficult and painful. I came out to my mother a few months before going abroad - I was about 25 or 26. And her reaction? Best left unrecorded. The dead cannot defend themselves. It was not kind. But remaining in hiding can also be harmful. What is not spoken of becomes the unspeakable. Adrienne Rich says that somewhere, I think. There’s a tacit assumption that there is something to be ashamed of, and that’s bad for a human being. It’s also bad for a writer; she is forced to speak in a voice that is not quite her own. And then the voice becomes stifled and loses its strength. I probably wanted to go abroad and study the English language anyway; but it’s also true that the impossibility of living honourably and openly as a lesbian forced an exile of sorts.

You come from a generation in India where hardly anyone was public and out as queer/lesbian. How did that journey happen for you? How did being a writer and diverse social responses to being lesbian shape that journey?It was difficult and painful. I came out to my mother a few months before going abroad - I was about 25 or 26. And her reaction? Best left unrecorded. The dead cannot defend themselves. It was not kind. But remaining in hiding can also be harmful. What is not spoken of becomes the unspeakable. Adrienne Rich says that somewhere, I think. There’s a tacit assumption that there is something to be ashamed of, and that’s bad for a human being. It’s also bad for a writer; she is forced to speak in a voice that is not quite her own. And then the voice becomes stifled and loses its strength. I probably wanted to go abroad and study the English language anyway; but it’s also true that the impossibility of living honourably and openly as a lesbian forced an exile of sorts. That hurt – or anger - does not seem to appear in your writing. When we’ve been hurt by the rejection of those close to us, what, if any, is the way back to a relationship with some love in it?

In everyone’s life there has usually been at least one person who has been loving, and that teaches us to love. It also heals us. There’s something about this in Goja. Time heals as well and also the realization that people who lash out are sometimes themselves in pain.

How do you think our sexual journeys – both, in our identity and as individuals – shape the rest of our lives? How do you think they change what we value in, art, life and relationships?

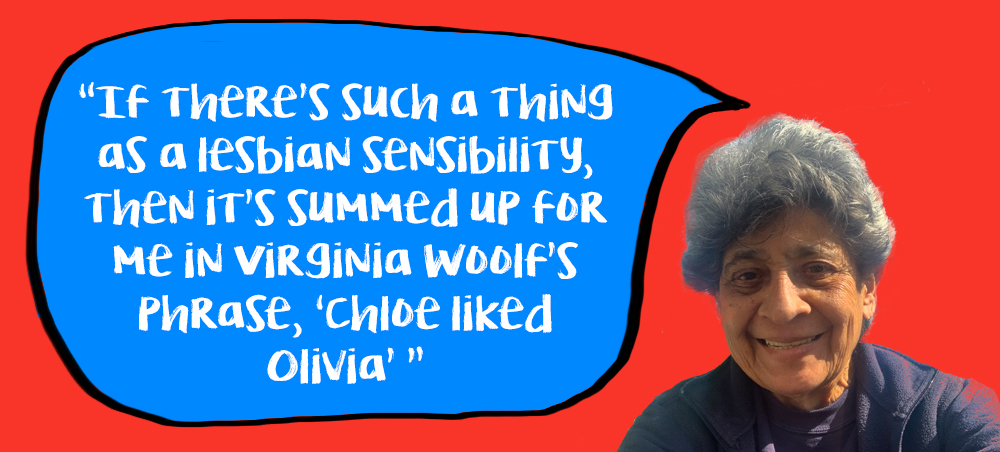

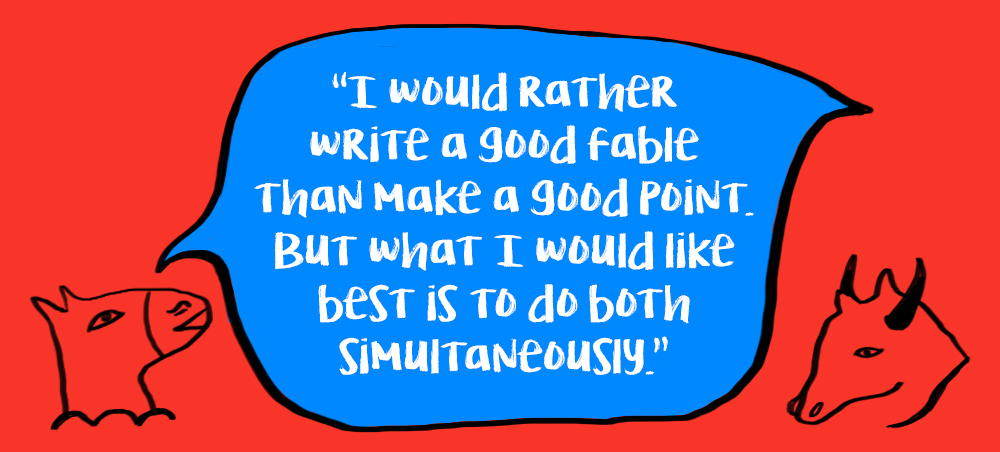

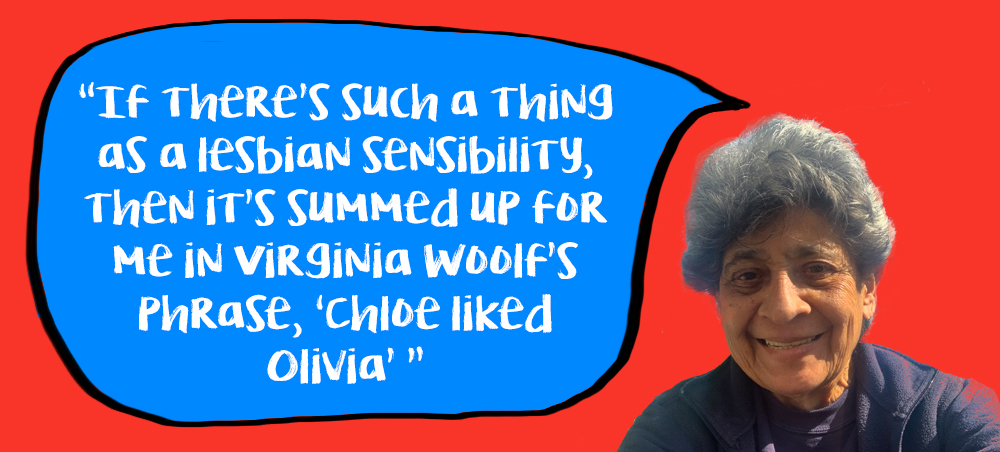

I think – I hope - that being oppressed for being lesbian has made me understand what it feels like to be oppressed for no good reason – for instance on the grounds of skin colour, caste, class and so forth – and has therefore politicized these issues for me and made me want to protest against injustice.If there’s such a thing as a lesbian sensibility, then it’s summed up for me in Virginia Woolf’s phrase, ‘Chloe liked Olivia.’ It’s a sensibility that likes and respects women even though we are considered ‘inferior’ within a patriarchy. In short it allows us to question the values of the prevailing hierarchy, and it makes us want to deal with people in an egalitarian way.And being a lesbian feminist has made me aware how some superb works of art are nevertheless marred by their sexism or their racism. You are tongue-in-cheek about herds/groups, yet not dismissive of community. What do you feel about the importance of movements as well as about the limits of movements for a young queer woman?Yes, the ambivalence about belonging to a group - I’m not sure why that happens. Perhaps all artists are like that. We live in time and therefore in flux. Aside from that, there’s something imprisoning about a fixed set of ideas. Movements tend to produce a party line. Perhaps that’s necessary for effective organization. And yet, movements can be hugely supportive and help the individual to challenge other orthodoxies. Your books often poke fun at political pieties, whether of feminism, or of sexual identities or of affiliations. You also ridicule the wanting to become sages and celebrities (The Blue Donkey Fables). The Mothers of Maya Diip, lays this out most clearly, layer by layer. At one point the Blue Donkey says “Look Madhu you’re just striking an attitude. Can’t you see it’s dangerous?” Why is this thought so central to your work?My instant response is: Because that sort of thing amounts to telling lies. You will say that poetry tells lies, fables tell lies. Yes, but they tell lies to get at something more accurate. Poets aren’t muddled by metaphors. They eat them for breakfast. But we are a symbol using species. We attach meaning to almost everything – eating, sleeping, drinking, love-making – and often we don’t realize we are doing it and we get confused and don’t even know why we are fighting or what we are aspiring to.  Your work is inherently queer in the sense that it defies categories. It is formal, yet emotional. It is political, yet without dogmas and by-rote positions. Do you think that for activists, this kind of work feels challenging and if yes, why? Are you in part, interested in presenting that challenge?I suppose if pushed into admitting it, I would say that I would rather write a good poem than a good manifesto. I would rather write a good fable than make a good point. But what I would like best is to do both simultaneously. There doesn’t have to be a contradiction between saying something worthwhile and saying it beautifully. A poem captures a pattern in movement. It isn’t static. And it makes a pattern out of sound, imagery and meaning itself. Perhaps it’s this resistance to something static, to something that can be paraphrased easily, that could be irritating to an activist insisting on political certainty. Poetry often appears in your books, almost in contrast with the spare prose, and it has a clear romanticism, even painfulness - almost like the film songs in an older Hindi films. In The Mothers of Maya Diip poetry is important – almost the most political and beautiful thing there can be. Why does poetry matters so much? What is its relationship to truth for you?We use language to think in. We use language like a butterfly net which we fling at the universe in order to make patterns out of it. And poetry expands, invents and stretches language beyond itself in an effort to say the unsayable. Many lesbian women in India, say they don’t like the word lesbian. A tiny percentage claim dyke, many choose queer, but there is some discomfort with what word to use, a discomfort which is not mirrored in conversations with gay men. Do you have a sense of why this might be so?I can understand the discomfort. Perhaps because the word has been used so often in a vituperative way, and at best savours of the medical. Poor Sappho and her beautiful island of Lesbos! I wish it reminded us instead of her poems. And ‘dyke’ is a ‘dirty word,’ which comes from blue jokes told against us. We’ve attempted to reclaim it – I’ve tried it once or twice in Feminist Fables. Here’s a poem by my partner, Gillian Hanscombe, which demonstrates the effect of patriarchal spite:No one is proud of dykes (not families not neigh-bours not friends not workmates not bosses notteachers not mentors not universities not literaturesocieties not any nation not any ruler not anybenefactor not any priest not any healer not any advocate). Only other dykes are proud of dykes.People say live and let live, but why should we? from Sybil: The Glide of Her Tongue (Spinifex, 1992)Perhaps we should call ourselves ‘gay,’ as well but that feels a little bit like defeat. Queer? That also has a particular meaning, hasn’t it?

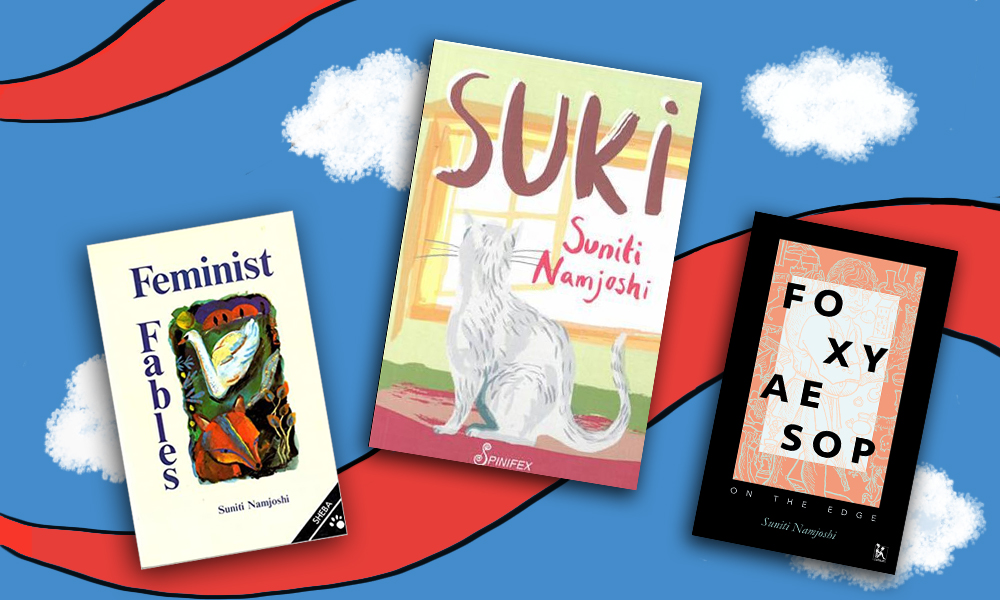

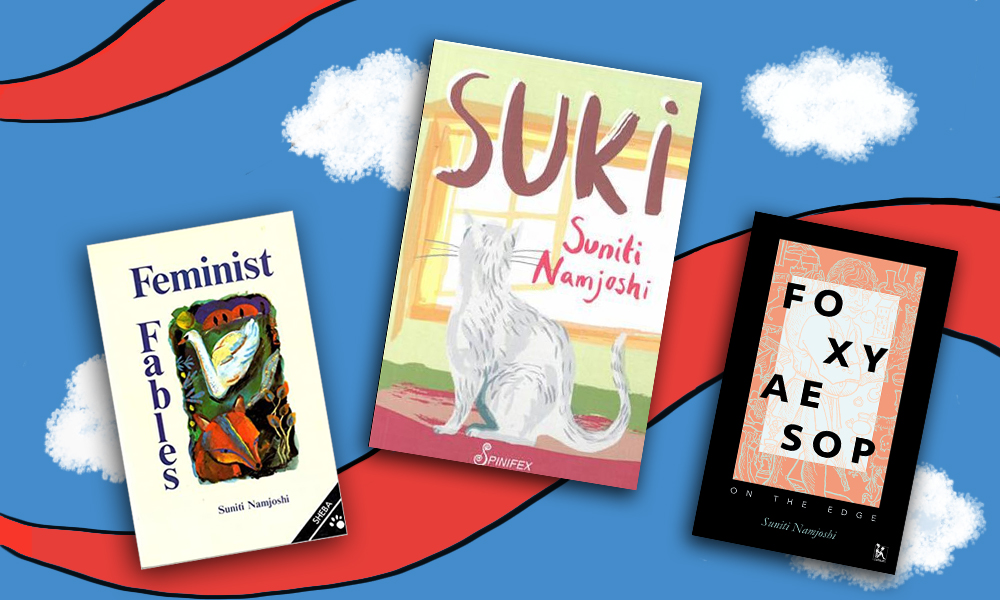

Your work is inherently queer in the sense that it defies categories. It is formal, yet emotional. It is political, yet without dogmas and by-rote positions. Do you think that for activists, this kind of work feels challenging and if yes, why? Are you in part, interested in presenting that challenge?I suppose if pushed into admitting it, I would say that I would rather write a good poem than a good manifesto. I would rather write a good fable than make a good point. But what I would like best is to do both simultaneously. There doesn’t have to be a contradiction between saying something worthwhile and saying it beautifully. A poem captures a pattern in movement. It isn’t static. And it makes a pattern out of sound, imagery and meaning itself. Perhaps it’s this resistance to something static, to something that can be paraphrased easily, that could be irritating to an activist insisting on political certainty. Poetry often appears in your books, almost in contrast with the spare prose, and it has a clear romanticism, even painfulness - almost like the film songs in an older Hindi films. In The Mothers of Maya Diip poetry is important – almost the most political and beautiful thing there can be. Why does poetry matters so much? What is its relationship to truth for you?We use language to think in. We use language like a butterfly net which we fling at the universe in order to make patterns out of it. And poetry expands, invents and stretches language beyond itself in an effort to say the unsayable. Many lesbian women in India, say they don’t like the word lesbian. A tiny percentage claim dyke, many choose queer, but there is some discomfort with what word to use, a discomfort which is not mirrored in conversations with gay men. Do you have a sense of why this might be so?I can understand the discomfort. Perhaps because the word has been used so often in a vituperative way, and at best savours of the medical. Poor Sappho and her beautiful island of Lesbos! I wish it reminded us instead of her poems. And ‘dyke’ is a ‘dirty word,’ which comes from blue jokes told against us. We’ve attempted to reclaim it – I’ve tried it once or twice in Feminist Fables. Here’s a poem by my partner, Gillian Hanscombe, which demonstrates the effect of patriarchal spite:No one is proud of dykes (not families not neigh-bours not friends not workmates not bosses notteachers not mentors not universities not literaturesocieties not any nation not any ruler not anybenefactor not any priest not any healer not any advocate). Only other dykes are proud of dykes.People say live and let live, but why should we? from Sybil: The Glide of Her Tongue (Spinifex, 1992)Perhaps we should call ourselves ‘gay,’ as well but that feels a little bit like defeat. Queer? That also has a particular meaning, hasn’t it?  What do you feel about the fact that Feminist Fables is your most known work? Not sure. Some of the fables in there are among my best work. But I’d like people to read some of the later work as well. Suki if you like cats – and meditation. Foxy Aesop if you like fables and Goja if you want to think about the polarities in India.

What do you feel about the fact that Feminist Fables is your most known work? Not sure. Some of the fables in there are among my best work. But I’d like people to read some of the later work as well. Suki if you like cats – and meditation. Foxy Aesop if you like fables and Goja if you want to think about the polarities in India.  At the present moment parts of the Indian queer community are keen that same-sex marriage should be legalized. Others feel that defeats the search for other ways to define and recognize relationships that feminism and queerness wish to do. In your own books you seem skeptical about marriage and motherhood. How do you feel about this? I’m sceptical about the role assigned to women in marriage within a patriarchy. It need not be like that. In practical terms being married can sometimes offer legal benefits to do with taxes and property rights, for example. Nor am I ‘sceptical’ about motherhood. But I do think we should be realistic about the sheer hard work and responsibility it involves. Our responsibility to ourselves as women and everyone’s responsibility to children do actually matter.

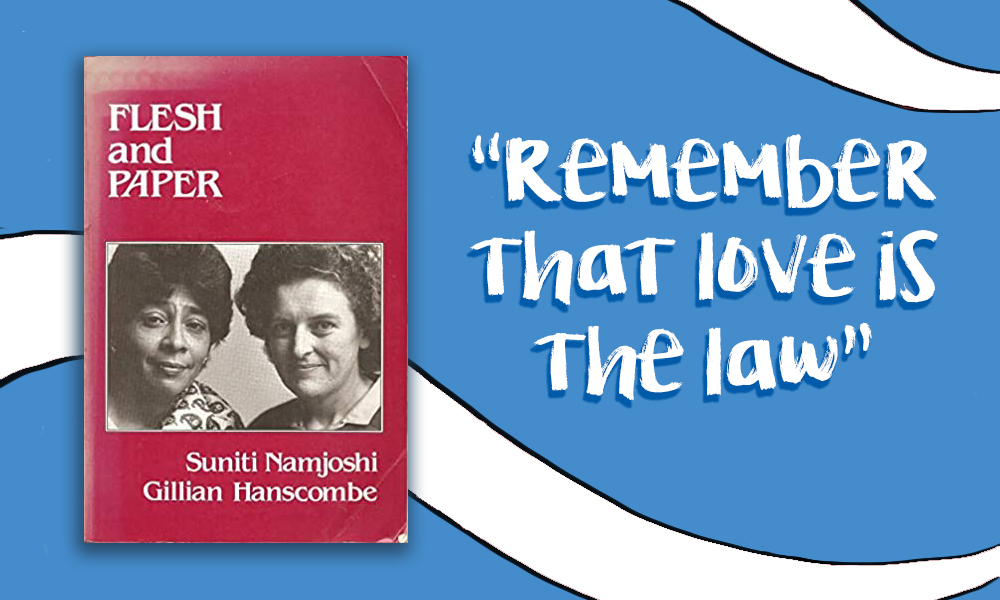

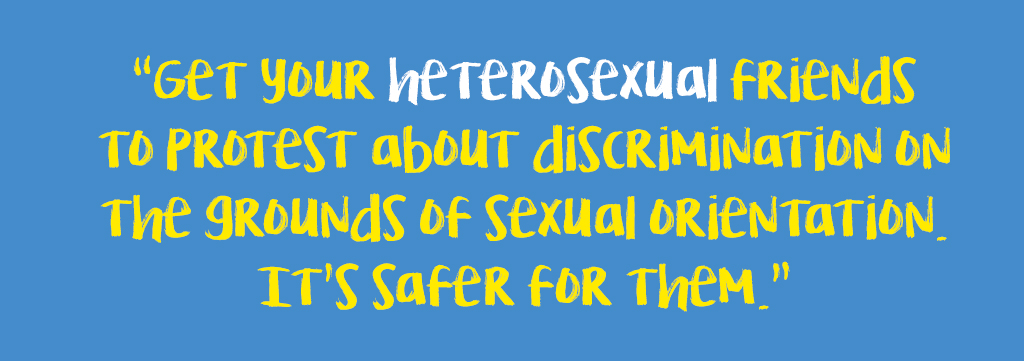

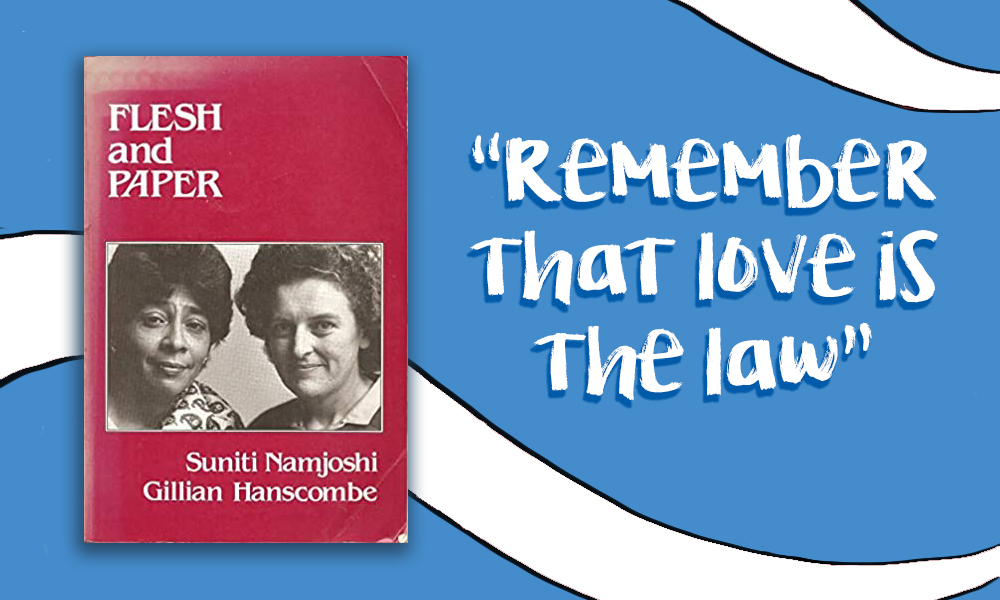

At the present moment parts of the Indian queer community are keen that same-sex marriage should be legalized. Others feel that defeats the search for other ways to define and recognize relationships that feminism and queerness wish to do. In your own books you seem skeptical about marriage and motherhood. How do you feel about this? I’m sceptical about the role assigned to women in marriage within a patriarchy. It need not be like that. In practical terms being married can sometimes offer legal benefits to do with taxes and property rights, for example. Nor am I ‘sceptical’ about motherhood. But I do think we should be realistic about the sheer hard work and responsibility it involves. Our responsibility to ourselves as women and everyone’s responsibility to children do actually matter.  What do you think love is? How can we have more of it in our lives – and in the world? It is our saving grace. As a species we can be unbelievably awful, but we can also love – our friends, our children, family, partners. Sexual love at its celebratory and joyful best is a language, a goddess, fire, energy. And the gentler, calmer love that makes us reach out to other people – even strangers sometimes – is perhaps what is best in us. What shreds of wisdom I have, I’m offering now – not because I’m wise, but because I care. So then, here’s my ‘good advice – in case it’s helpful.If you want to live your life on your own terms, make sure you have a means of livelihood. Acquire a skill, get a job, some sort of financial independence.Don’t come out unless you feel it’s safe to do so and are strong enough to bear the consequences. It’s a weapon that can be used against you for all sorts of reasons - to do you out of property, a job, status in society. Get your heterosexual friends to protest about discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. It’s safer for them. Being victimised isn’t shameful. It’s doing the victimisation that is ugly and shameful.And sexuality in itself is not a moral issue. The willingness to hurt, hate and kill is. Because you’ve been hurt in this arbitrary way, protest against anyone else being hurt similarly, say for reasons of caste, class, religion. And remember that love is the law. Many years ago when my partner Gill and I first met, we wrote each other a series of poems. I want to share one of the poems – and its message - with you.All the wordsAll the words have leaped into air like the cardsin Alice, like birds flying, forming, reforming,swerving and rising, and each wordsays it is love. The cat says it is love.It says, “I am and I love.” And the fawnin the forest who lost his name, he eatsfrom your hand. He tells you, “My name is love.”And all the White Knight’s baggage rattles, and criesit is love. And even the tiger-lily even the rosesay only that they are themselves. And they saythey are love. All the little words saythey are love, the space in between, the linkand logic of love. And I can make no headwayin this heady grammar, and suddenlyand here, you are, I am, and we love. from Flesh and Paper 1986, also in The Fabulous Feminist

What do you think love is? How can we have more of it in our lives – and in the world? It is our saving grace. As a species we can be unbelievably awful, but we can also love – our friends, our children, family, partners. Sexual love at its celebratory and joyful best is a language, a goddess, fire, energy. And the gentler, calmer love that makes us reach out to other people – even strangers sometimes – is perhaps what is best in us. What shreds of wisdom I have, I’m offering now – not because I’m wise, but because I care. So then, here’s my ‘good advice – in case it’s helpful.If you want to live your life on your own terms, make sure you have a means of livelihood. Acquire a skill, get a job, some sort of financial independence.Don’t come out unless you feel it’s safe to do so and are strong enough to bear the consequences. It’s a weapon that can be used against you for all sorts of reasons - to do you out of property, a job, status in society. Get your heterosexual friends to protest about discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. It’s safer for them. Being victimised isn’t shameful. It’s doing the victimisation that is ugly and shameful.And sexuality in itself is not a moral issue. The willingness to hurt, hate and kill is. Because you’ve been hurt in this arbitrary way, protest against anyone else being hurt similarly, say for reasons of caste, class, religion. And remember that love is the law. Many years ago when my partner Gill and I first met, we wrote each other a series of poems. I want to share one of the poems – and its message - with you.All the wordsAll the words have leaped into air like the cardsin Alice, like birds flying, forming, reforming,swerving and rising, and each wordsays it is love. The cat says it is love.It says, “I am and I love.” And the fawnin the forest who lost his name, he eatsfrom your hand. He tells you, “My name is love.”And all the White Knight’s baggage rattles, and criesit is love. And even the tiger-lily even the rosesay only that they are themselves. And they saythey are love. All the little words saythey are love, the space in between, the linkand logic of love. And I can make no headwayin this heady grammar, and suddenlyand here, you are, I am, and we love. from Flesh and Paper 1986, also in The Fabulous Feminist

Score:

0/

Suniti Namjoshi was born in 1941, served in the IAS for a while, and wrote Feminist Fables in 1981. She is a novelist, fabulist, poet, lesbian, feminist and one of the warmest, wisest, funniest voices to come out of India. If you read one of her books – say, Conversations with Cow, The Blue Donkey Fables, The Mothers of Maya Diip, Goja: An Autobiographical Myth, Saint Suniti and the Dragon and many others, you will laugh out loud and say Yes! Exactly! even if you are alone in the room.. If you’ve been part of groups and organisations, you will recognize many #BoreMatKarYaar types pompous behaviours and rigid positions, and feel amused and relieved that you can make fun of that with affection, and without ever mocking or denouncing individuals or betraying political ideals. There is intimacy and there is distance and they dance together in her pithy fables, fertile poems and tart lines.Her work is deeply political because it is deeply pleasurable, and completely free of ideological orthodoxy. It is also so Indian because it doesn’t try to be, but it has that karara sarcasm we know from so many Indian languages. It searches for the heart of fairness and freedom with mischief, irony, marvelous animal characters, unique lady people and beautiful sentences. A tasting menu of her work is to be found in The Fabulous Feminist: A Suniti Namjoshi Reader, published by Zubaan, so go do some gourmet overeating. She spoke to Agents of Ishq about her writing choices – why she chooses to work with fables for instance – what her lesbian identity means for her life and work, and her journey as a writer, a lover and a person.Yes, we did ask her “what is love?”. And yes, she did answer. So, read on.

Suniti Namjoshi was born in 1941, served in the IAS for a while, and wrote Feminist Fables in 1981. She is a novelist, fabulist, poet, lesbian, feminist and one of the warmest, wisest, funniest voices to come out of India. If you read one of her books – say, Conversations with Cow, The Blue Donkey Fables, The Mothers of Maya Diip, Goja: An Autobiographical Myth, Saint Suniti and the Dragon and many others, you will laugh out loud and say Yes! Exactly! even if you are alone in the room.. If you’ve been part of groups and organisations, you will recognize many #BoreMatKarYaar types pompous behaviours and rigid positions, and feel amused and relieved that you can make fun of that with affection, and without ever mocking or denouncing individuals or betraying political ideals. There is intimacy and there is distance and they dance together in her pithy fables, fertile poems and tart lines.Her work is deeply political because it is deeply pleasurable, and completely free of ideological orthodoxy. It is also so Indian because it doesn’t try to be, but it has that karara sarcasm we know from so many Indian languages. It searches for the heart of fairness and freedom with mischief, irony, marvelous animal characters, unique lady people and beautiful sentences. A tasting menu of her work is to be found in The Fabulous Feminist: A Suniti Namjoshi Reader, published by Zubaan, so go do some gourmet overeating. She spoke to Agents of Ishq about her writing choices – why she chooses to work with fables for instance – what her lesbian identity means for her life and work, and her journey as a writer, a lover and a person.Yes, we did ask her “what is love?”. And yes, she did answer. So, read on.  The Blue Donkey Fables and then The Conversations of Cow have a thrilling interplay – there is the economy of form, which is so precise, and whimsical humour, which feels almost casually plentiful. What do you want to bring alive for the reader with this combination?Being told that is thrilling for me too – for any writer probably! A lot of hard work goes into the writing and then there’s the necessary ten percent of luck or inspiration. I want my work to produce a feeling of strength from its clarity and of joy from the way it all works together. Searching for you online sometimes finds you described as a lesbian writer. How do you relate to that description?Well, that was what I took on when I decided it was necessary to come out and say to people that I and other lesbians by implication are human – one nose , two eyes etc.

The Blue Donkey Fables and then The Conversations of Cow have a thrilling interplay – there is the economy of form, which is so precise, and whimsical humour, which feels almost casually plentiful. What do you want to bring alive for the reader with this combination?Being told that is thrilling for me too – for any writer probably! A lot of hard work goes into the writing and then there’s the necessary ten percent of luck or inspiration. I want my work to produce a feeling of strength from its clarity and of joy from the way it all works together. Searching for you online sometimes finds you described as a lesbian writer. How do you relate to that description?Well, that was what I took on when I decided it was necessary to come out and say to people that I and other lesbians by implication are human – one nose , two eyes etc.  You use poetry, fable, autobiographical myth and so on over more commonly found realist political forms, while talking about identity, sexuality and the dynamics between groups and people. Do you think of your work as political? In what way would you describe its political-ness?I haven’t chosen these forms consciously. By temperament all I want to do is try to write a good poem or a good fable and hide behind a book. I didn’t want to engage in lesbian feminist politics. I did so, because I realized that other people, especially my friend and ex-partner Christine Donald aka Hilary Clare, were fighting my battles for me. It wouldn’t have been fair just to sit back. I also realized that politics has something to do with ethics. Luckily for me the fable, which is a form that comes easily to me, is a didactic form. I don’t necessarily want to tell people what to think, but I do want them to think.

You use poetry, fable, autobiographical myth and so on over more commonly found realist political forms, while talking about identity, sexuality and the dynamics between groups and people. Do you think of your work as political? In what way would you describe its political-ness?I haven’t chosen these forms consciously. By temperament all I want to do is try to write a good poem or a good fable and hide behind a book. I didn’t want to engage in lesbian feminist politics. I did so, because I realized that other people, especially my friend and ex-partner Christine Donald aka Hilary Clare, were fighting my battles for me. It wouldn’t have been fair just to sit back. I also realized that politics has something to do with ethics. Luckily for me the fable, which is a form that comes easily to me, is a didactic form. I don’t necessarily want to tell people what to think, but I do want them to think.  Your book The Mothers of Maya Diip, is a dystopian novel in which a matriarchy prevails. It seems to question utopia, without negating a search for the utopian. What fuelled this book and the way it is written?Protesting against oppression makes us feel that we are in the right. But we are only right in that particular respect. As women, as human beings, we have to question ourselves as well. I wanted to see how a society dominated by women might work and the ways in which we too might be susceptible to corruption. I also wanted to demonstrate how the ‘norms’ in a society - however bizarre - govern interactions. The search for the utopian has to be an ongoing quest perhaps as perfection would be static.

Your book The Mothers of Maya Diip, is a dystopian novel in which a matriarchy prevails. It seems to question utopia, without negating a search for the utopian. What fuelled this book and the way it is written?Protesting against oppression makes us feel that we are in the right. But we are only right in that particular respect. As women, as human beings, we have to question ourselves as well. I wanted to see how a society dominated by women might work and the ways in which we too might be susceptible to corruption. I also wanted to demonstrate how the ‘norms’ in a society - however bizarre - govern interactions. The search for the utopian has to be an ongoing quest perhaps as perfection would be static.  One way of reading The Conversations of Cow is to see it as a relationship story and also a little bit of a coming out to/with yourself kind of story. Why do you think you never wanted to talk about these experiences in a straightforward direct way?It wasn’t intended as a coming out story. I was part of the lesbian feminist movement in Canada and later in Britain, but I did want to question some aspects of the party line without undermining the movement. That’s why I chose my own name for the central character. Suniti gets into all sorts of trouble coping with gender stereotyping, problems of identity and her own preconceptions. I have said something about my own experience in a more straightforward way in the introductions to the different sections of The Fabulous Feminist (Zubaan, 2012). The book contains excerpts from several of my books and explains the context in which I came to write a particular work. And Goja is, after all, an autobiographical myth. Saying something outright is not necessarily a more accurate version of experience, though it can be devastating. That too is part of the craft. The form I choose depends on what I’m trying to do. And also I have to be able to use the form.

One way of reading The Conversations of Cow is to see it as a relationship story and also a little bit of a coming out to/with yourself kind of story. Why do you think you never wanted to talk about these experiences in a straightforward direct way?It wasn’t intended as a coming out story. I was part of the lesbian feminist movement in Canada and later in Britain, but I did want to question some aspects of the party line without undermining the movement. That’s why I chose my own name for the central character. Suniti gets into all sorts of trouble coping with gender stereotyping, problems of identity and her own preconceptions. I have said something about my own experience in a more straightforward way in the introductions to the different sections of The Fabulous Feminist (Zubaan, 2012). The book contains excerpts from several of my books and explains the context in which I came to write a particular work. And Goja is, after all, an autobiographical myth. Saying something outright is not necessarily a more accurate version of experience, though it can be devastating. That too is part of the craft. The form I choose depends on what I’m trying to do. And also I have to be able to use the form.  Your books often feature a character called Suniti. She isn’t the same character, though she does have similar characteristics of being very sincere and sometimes nonplussed by events, like the straight man in old comedies. Why does Suniti appear in this way?I use the ‘Suniti’ name in different ways in different books. In The Conversations of Cow it allows me to soften the satire against a well meaning lesbian feminist. It also allows me to bring in the Indian background with just one word, and without muddying the narrative with a lengthy explanation. And in Saint Suniti and the Dragon it allows me to depict the three locations of her struggle to be good: within her psyche, within the text, and in the ‘real’ world.

Your books often feature a character called Suniti. She isn’t the same character, though she does have similar characteristics of being very sincere and sometimes nonplussed by events, like the straight man in old comedies. Why does Suniti appear in this way?I use the ‘Suniti’ name in different ways in different books. In The Conversations of Cow it allows me to soften the satire against a well meaning lesbian feminist. It also allows me to bring in the Indian background with just one word, and without muddying the narrative with a lengthy explanation. And in Saint Suniti and the Dragon it allows me to depict the three locations of her struggle to be good: within her psyche, within the text, and in the ‘real’ world.  You come from a generation in India where hardly anyone was public and out as queer/lesbian. How did that journey happen for you? How did being a writer and diverse social responses to being lesbian shape that journey?It was difficult and painful. I came out to my mother a few months before going abroad - I was about 25 or 26. And her reaction? Best left unrecorded. The dead cannot defend themselves. It was not kind. But remaining in hiding can also be harmful. What is not spoken of becomes the unspeakable. Adrienne Rich says that somewhere, I think. There’s a tacit assumption that there is something to be ashamed of, and that’s bad for a human being. It’s also bad for a writer; she is forced to speak in a voice that is not quite her own. And then the voice becomes stifled and loses its strength. I probably wanted to go abroad and study the English language anyway; but it’s also true that the impossibility of living honourably and openly as a lesbian forced an exile of sorts.

You come from a generation in India where hardly anyone was public and out as queer/lesbian. How did that journey happen for you? How did being a writer and diverse social responses to being lesbian shape that journey?It was difficult and painful. I came out to my mother a few months before going abroad - I was about 25 or 26. And her reaction? Best left unrecorded. The dead cannot defend themselves. It was not kind. But remaining in hiding can also be harmful. What is not spoken of becomes the unspeakable. Adrienne Rich says that somewhere, I think. There’s a tacit assumption that there is something to be ashamed of, and that’s bad for a human being. It’s also bad for a writer; she is forced to speak in a voice that is not quite her own. And then the voice becomes stifled and loses its strength. I probably wanted to go abroad and study the English language anyway; but it’s also true that the impossibility of living honourably and openly as a lesbian forced an exile of sorts.

Your work is inherently queer in the sense that it defies categories. It is formal, yet emotional. It is political, yet without dogmas and by-rote positions. Do you think that for activists, this kind of work feels challenging and if yes, why? Are you in part, interested in presenting that challenge?I suppose if pushed into admitting it, I would say that I would rather write a good poem than a good manifesto. I would rather write a good fable than make a good point. But what I would like best is to do both simultaneously. There doesn’t have to be a contradiction between saying something worthwhile and saying it beautifully. A poem captures a pattern in movement. It isn’t static. And it makes a pattern out of sound, imagery and meaning itself. Perhaps it’s this resistance to something static, to something that can be paraphrased easily, that could be irritating to an activist insisting on political certainty. Poetry often appears in your books, almost in contrast with the spare prose, and it has a clear romanticism, even painfulness - almost like the film songs in an older Hindi films. In The Mothers of Maya Diip poetry is important – almost the most political and beautiful thing there can be. Why does poetry matters so much? What is its relationship to truth for you?We use language to think in. We use language like a butterfly net which we fling at the universe in order to make patterns out of it. And poetry expands, invents and stretches language beyond itself in an effort to say the unsayable. Many lesbian women in India, say they don’t like the word lesbian. A tiny percentage claim dyke, many choose queer, but there is some discomfort with what word to use, a discomfort which is not mirrored in conversations with gay men. Do you have a sense of why this might be so?I can understand the discomfort. Perhaps because the word has been used so often in a vituperative way, and at best savours of the medical. Poor Sappho and her beautiful island of Lesbos! I wish it reminded us instead of her poems. And ‘dyke’ is a ‘dirty word,’ which comes from blue jokes told against us. We’ve attempted to reclaim it – I’ve tried it once or twice in Feminist Fables. Here’s a poem by my partner, Gillian Hanscombe, which demonstrates the effect of patriarchal spite:No one is proud of dykes (not families not neigh-bours not friends not workmates not bosses notteachers not mentors not universities not literaturesocieties not any nation not any ruler not anybenefactor not any priest not any healer not any advocate). Only other dykes are proud of dykes.People say live and let live, but why should we? from Sybil: The Glide of Her Tongue (Spinifex, 1992)Perhaps we should call ourselves ‘gay,’ as well but that feels a little bit like defeat. Queer? That also has a particular meaning, hasn’t it?

Your work is inherently queer in the sense that it defies categories. It is formal, yet emotional. It is political, yet without dogmas and by-rote positions. Do you think that for activists, this kind of work feels challenging and if yes, why? Are you in part, interested in presenting that challenge?I suppose if pushed into admitting it, I would say that I would rather write a good poem than a good manifesto. I would rather write a good fable than make a good point. But what I would like best is to do both simultaneously. There doesn’t have to be a contradiction between saying something worthwhile and saying it beautifully. A poem captures a pattern in movement. It isn’t static. And it makes a pattern out of sound, imagery and meaning itself. Perhaps it’s this resistance to something static, to something that can be paraphrased easily, that could be irritating to an activist insisting on political certainty. Poetry often appears in your books, almost in contrast with the spare prose, and it has a clear romanticism, even painfulness - almost like the film songs in an older Hindi films. In The Mothers of Maya Diip poetry is important – almost the most political and beautiful thing there can be. Why does poetry matters so much? What is its relationship to truth for you?We use language to think in. We use language like a butterfly net which we fling at the universe in order to make patterns out of it. And poetry expands, invents and stretches language beyond itself in an effort to say the unsayable. Many lesbian women in India, say they don’t like the word lesbian. A tiny percentage claim dyke, many choose queer, but there is some discomfort with what word to use, a discomfort which is not mirrored in conversations with gay men. Do you have a sense of why this might be so?I can understand the discomfort. Perhaps because the word has been used so often in a vituperative way, and at best savours of the medical. Poor Sappho and her beautiful island of Lesbos! I wish it reminded us instead of her poems. And ‘dyke’ is a ‘dirty word,’ which comes from blue jokes told against us. We’ve attempted to reclaim it – I’ve tried it once or twice in Feminist Fables. Here’s a poem by my partner, Gillian Hanscombe, which demonstrates the effect of patriarchal spite:No one is proud of dykes (not families not neigh-bours not friends not workmates not bosses notteachers not mentors not universities not literaturesocieties not any nation not any ruler not anybenefactor not any priest not any healer not any advocate). Only other dykes are proud of dykes.People say live and let live, but why should we? from Sybil: The Glide of Her Tongue (Spinifex, 1992)Perhaps we should call ourselves ‘gay,’ as well but that feels a little bit like defeat. Queer? That also has a particular meaning, hasn’t it?  What do you feel about the fact that Feminist Fables is your most known work? Not sure. Some of the fables in there are among my best work. But I’d like people to read some of the later work as well. Suki if you like cats – and meditation. Foxy Aesop if you like fables and Goja if you want to think about the polarities in India.

What do you feel about the fact that Feminist Fables is your most known work? Not sure. Some of the fables in there are among my best work. But I’d like people to read some of the later work as well. Suki if you like cats – and meditation. Foxy Aesop if you like fables and Goja if you want to think about the polarities in India.  At the present moment parts of the Indian queer community are keen that same-sex marriage should be legalized. Others feel that defeats the search for other ways to define and recognize relationships that feminism and queerness wish to do. In your own books you seem skeptical about marriage and motherhood. How do you feel about this? I’m sceptical about the role assigned to women in marriage within a patriarchy. It need not be like that. In practical terms being married can sometimes offer legal benefits to do with taxes and property rights, for example. Nor am I ‘sceptical’ about motherhood. But I do think we should be realistic about the sheer hard work and responsibility it involves. Our responsibility to ourselves as women and everyone’s responsibility to children do actually matter.

At the present moment parts of the Indian queer community are keen that same-sex marriage should be legalized. Others feel that defeats the search for other ways to define and recognize relationships that feminism and queerness wish to do. In your own books you seem skeptical about marriage and motherhood. How do you feel about this? I’m sceptical about the role assigned to women in marriage within a patriarchy. It need not be like that. In practical terms being married can sometimes offer legal benefits to do with taxes and property rights, for example. Nor am I ‘sceptical’ about motherhood. But I do think we should be realistic about the sheer hard work and responsibility it involves. Our responsibility to ourselves as women and everyone’s responsibility to children do actually matter.  What do you think love is? How can we have more of it in our lives – and in the world? It is our saving grace. As a species we can be unbelievably awful, but we can also love – our friends, our children, family, partners. Sexual love at its celebratory and joyful best is a language, a goddess, fire, energy. And the gentler, calmer love that makes us reach out to other people – even strangers sometimes – is perhaps what is best in us. What shreds of wisdom I have, I’m offering now – not because I’m wise, but because I care. So then, here’s my ‘good advice – in case it’s helpful.If you want to live your life on your own terms, make sure you have a means of livelihood. Acquire a skill, get a job, some sort of financial independence.Don’t come out unless you feel it’s safe to do so and are strong enough to bear the consequences. It’s a weapon that can be used against you for all sorts of reasons - to do you out of property, a job, status in society. Get your heterosexual friends to protest about discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. It’s safer for them. Being victimised isn’t shameful. It’s doing the victimisation that is ugly and shameful.And sexuality in itself is not a moral issue. The willingness to hurt, hate and kill is. Because you’ve been hurt in this arbitrary way, protest against anyone else being hurt similarly, say for reasons of caste, class, religion. And remember that love is the law. Many years ago when my partner Gill and I first met, we wrote each other a series of poems. I want to share one of the poems – and its message - with you.All the wordsAll the words have leaped into air like the cardsin Alice, like birds flying, forming, reforming,swerving and rising, and each wordsays it is love. The cat says it is love.It says, “I am and I love.” And the fawnin the forest who lost his name, he eatsfrom your hand. He tells you, “My name is love.”And all the White Knight’s baggage rattles, and criesit is love. And even the tiger-lily even the rosesay only that they are themselves. And they saythey are love. All the little words saythey are love, the space in between, the linkand logic of love. And I can make no headwayin this heady grammar, and suddenlyand here, you are, I am, and we love. from Flesh and Paper 1986, also in The Fabulous Feminist

What do you think love is? How can we have more of it in our lives – and in the world? It is our saving grace. As a species we can be unbelievably awful, but we can also love – our friends, our children, family, partners. Sexual love at its celebratory and joyful best is a language, a goddess, fire, energy. And the gentler, calmer love that makes us reach out to other people – even strangers sometimes – is perhaps what is best in us. What shreds of wisdom I have, I’m offering now – not because I’m wise, but because I care. So then, here’s my ‘good advice – in case it’s helpful.If you want to live your life on your own terms, make sure you have a means of livelihood. Acquire a skill, get a job, some sort of financial independence.Don’t come out unless you feel it’s safe to do so and are strong enough to bear the consequences. It’s a weapon that can be used against you for all sorts of reasons - to do you out of property, a job, status in society. Get your heterosexual friends to protest about discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. It’s safer for them. Being victimised isn’t shameful. It’s doing the victimisation that is ugly and shameful.And sexuality in itself is not a moral issue. The willingness to hurt, hate and kill is. Because you’ve been hurt in this arbitrary way, protest against anyone else being hurt similarly, say for reasons of caste, class, religion. And remember that love is the law. Many years ago when my partner Gill and I first met, we wrote each other a series of poems. I want to share one of the poems – and its message - with you.All the wordsAll the words have leaped into air like the cardsin Alice, like birds flying, forming, reforming,swerving and rising, and each wordsays it is love. The cat says it is love.It says, “I am and I love.” And the fawnin the forest who lost his name, he eatsfrom your hand. He tells you, “My name is love.”And all the White Knight’s baggage rattles, and criesit is love. And even the tiger-lily even the rosesay only that they are themselves. And they saythey are love. All the little words saythey are love, the space in between, the linkand logic of love. And I can make no headwayin this heady grammar, and suddenlyand here, you are, I am, and we love. from Flesh and Paper 1986, also in The Fabulous Feminist