The world has been shaken up in the last few months, but not Tamil cinema. We get the same eyeroll- inducing stories about men coming of age. The beloved Vinnaithaandi Varuvaaya (VTV; 2010) was a story about Karthik, a passionate boy, his love, loss, and ultimate journey to creative success for which his love remains an inspiration, and his erstwhile lover, Jessie, a muse. The sequel, Karthik Dial Seytha Yenn (KDSY), which dropped recently, is… much the same. Karthik is suffering a writing block in COVID-imposed isolation, and at the end of twelve minutes, a telephone conversation with a now-married Jessie has fished him out of it. There is hope for him yet: if not his love life, his creative journey.  I am not newly annoyed by this plotline, just triggered afresh. Particularly annoying is the fact that Jessie is a character that has the potential to be interesting in her own merit, instead of being just the conventionally beautiful ideal in the most perfectly draped saris, not a hair out of place. In VTV, she’s caught in a real predicament between her feelings for this boy and her conservative family. She makes some brave choices for a while, but ultimately in a moment of difficulty, ends up choosing to comply with her family than work to have her love for Karthik come through. Fair, that’s Jessie, and perhaps a great many women who are subject to a great deal of societal and parental pressure to be married off to appropriate men, in real life and in the movies. The interesting part is that we get a little taste of what Jessie could be…

I am not newly annoyed by this plotline, just triggered afresh. Particularly annoying is the fact that Jessie is a character that has the potential to be interesting in her own merit, instead of being just the conventionally beautiful ideal in the most perfectly draped saris, not a hair out of place. In VTV, she’s caught in a real predicament between her feelings for this boy and her conservative family. She makes some brave choices for a while, but ultimately in a moment of difficulty, ends up choosing to comply with her family than work to have her love for Karthik come through. Fair, that’s Jessie, and perhaps a great many women who are subject to a great deal of societal and parental pressure to be married off to appropriate men, in real life and in the movies. The interesting part is that we get a little taste of what Jessie could be…  In Karthik’s movie within the movie, Jessie gives him up for her parents, but doesn’t give in to their demand to marry a boy they have found for her. And that was a woman that made a more uphill, even befuddling choice, and lived with the lonely repercussions of that choice for a bit. (“I haven’t moved on, Karthik,” she declares when they run into each other a few years later.) Perhaps that wasn’t authentically her – maybe it was only Karthik’s wishful thinking. Maybe it was. But I keep wondering what Jessie’s life was like in those years. She wasn’t in touch with him. She had moved halfway across the world. Was she trying to move on? What was she hoping for, what was she thinking? What’s actually going on with the single (or single-ish) ladies in the movies?

In Karthik’s movie within the movie, Jessie gives him up for her parents, but doesn’t give in to their demand to marry a boy they have found for her. And that was a woman that made a more uphill, even befuddling choice, and lived with the lonely repercussions of that choice for a bit. (“I haven’t moved on, Karthik,” she declares when they run into each other a few years later.) Perhaps that wasn’t authentically her – maybe it was only Karthik’s wishful thinking. Maybe it was. But I keep wondering what Jessie’s life was like in those years. She wasn’t in touch with him. She had moved halfway across the world. Was she trying to move on? What was she hoping for, what was she thinking? What’s actually going on with the single (or single-ish) ladies in the movies?

A case for the soup girl

It seems like a pretty basic thing to say, but watching Tamil cinema, one wouldn’t guess that women get their hearts broken too. Much like men, women do feel such things as regret, disappointment, devastation, humiliation, and longing, sometimes for extended periods of time. They don’t all resignedly slide into the perceived security of marriage, usually arranged with parent-approved, patient, kind men in which they heal, their rough edges straightened out (also because #husbandisgod; in the classic plotlines of Andha 7 Naatkal (1981), Mouna Ragam (1986)). There’s no “practical,” inevitable destiny for all women in real life. There’s apparently over 74 million single women in India. Who would’ve thunk, eh?  Now, I do not want to understate or simplify the immense pressures faced by all people to conform in a deeply patriarchal society. Dominant views of masculinity demand that men have stable careers and provide financial security to the heteronormative family, while it is a well-established fact that women do almost all the care work, both within the household and in society in general. But men in the movies get to push back against these expectations, in the various iterations of Karthik. They get the opportunities to be wastrels, whether or not they can afford to be (the Devdas trope), sometimes berating his most lofty love for having white skin and a black, fickle heart (Kolaveri di, to which we perhaps owe the coinage of ‘soup boy’, and a host of other songs and sentiments that thrive in Tamil cinema). In some others, the men get to be angsty artists who persevere at creative careers even in the face of financial pressures (like in KDSY). They get to be messy, determined, and passionate, while the women are pushed down the practical, grown-up roads, into stable structures assembled by their families. (Firstly, what is particularly “grown-up” about unquestioningly fitting into dangerously endogamous templates deemed appropriate by an insular society?) Where are the women that fall through the cracks, due to choice, chance, or some combination of the two? Where are the messy, passionate, disobedient, resisting, sometimes unlucky, lonely women, the “not yet” women, the “not again,” the “don’t give a flying fuck” women?

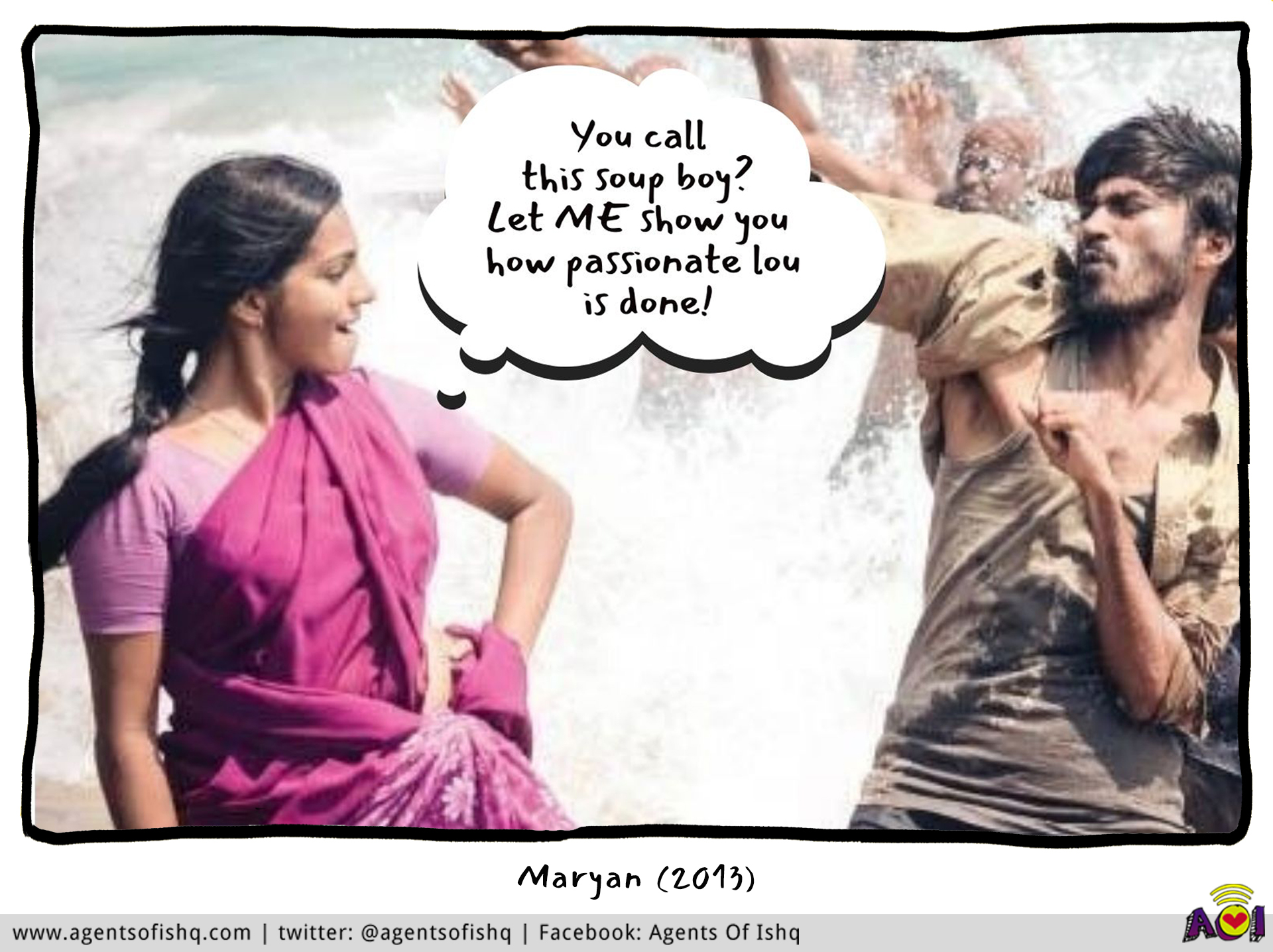

Now, I do not want to understate or simplify the immense pressures faced by all people to conform in a deeply patriarchal society. Dominant views of masculinity demand that men have stable careers and provide financial security to the heteronormative family, while it is a well-established fact that women do almost all the care work, both within the household and in society in general. But men in the movies get to push back against these expectations, in the various iterations of Karthik. They get the opportunities to be wastrels, whether or not they can afford to be (the Devdas trope), sometimes berating his most lofty love for having white skin and a black, fickle heart (Kolaveri di, to which we perhaps owe the coinage of ‘soup boy’, and a host of other songs and sentiments that thrive in Tamil cinema). In some others, the men get to be angsty artists who persevere at creative careers even in the face of financial pressures (like in KDSY). They get to be messy, determined, and passionate, while the women are pushed down the practical, grown-up roads, into stable structures assembled by their families. (Firstly, what is particularly “grown-up” about unquestioningly fitting into dangerously endogamous templates deemed appropriate by an insular society?) Where are the women that fall through the cracks, due to choice, chance, or some combination of the two? Where are the messy, passionate, disobedient, resisting, sometimes unlucky, lonely women, the “not yet” women, the “not again,” the “don’t give a flying fuck” women?  Am I asking for a soup girl? I am, even if tentatively. I could produce tomes from my own personal experience of being unmarried at 32, about the immense anxiety and bewilderment surrounding the unattached woman. Even seemingly liberal households spout frequent clichés and tears about parental duty, the sanctity of creating one’s “own family” and “settling down,” the need for companionship, and so forth, when she does not fulfill these expectations in her respectable twenties. The pressure is real, and any choice is complicated. The problem with soup boy songs is precisely the erasure of this reality, in order to shore up the girl’s supposed cruelty and the men’s own righteous self-pity. We almost never get any sense of a woman’s internal or external life as she deliberates on these matters. (Uma Devi’s lyrics in ’96 give us a little to chew on, but the movie itself is really about “the life of Ram” revealing too little about Jaanu in this movie about childhood sweethearts meeting at a school reunion.) No matter how “respectfully” Jaanu and Jessie are treated in their movie universes: if we don’t hear their perspectives, they remain objects, if highly idealized objects in a male gaze way past its “best by” date. Women also love passionately, we know that. I think of the women who are open and persistent about their desires in Thambikku endha ooru (1984), Paruthiveeran (2007), Maryan (2013) among others, to the extent that they annoy the objects of their affection.

Am I asking for a soup girl? I am, even if tentatively. I could produce tomes from my own personal experience of being unmarried at 32, about the immense anxiety and bewilderment surrounding the unattached woman. Even seemingly liberal households spout frequent clichés and tears about parental duty, the sanctity of creating one’s “own family” and “settling down,” the need for companionship, and so forth, when she does not fulfill these expectations in her respectable twenties. The pressure is real, and any choice is complicated. The problem with soup boy songs is precisely the erasure of this reality, in order to shore up the girl’s supposed cruelty and the men’s own righteous self-pity. We almost never get any sense of a woman’s internal or external life as she deliberates on these matters. (Uma Devi’s lyrics in ’96 give us a little to chew on, but the movie itself is really about “the life of Ram” revealing too little about Jaanu in this movie about childhood sweethearts meeting at a school reunion.) No matter how “respectfully” Jaanu and Jessie are treated in their movie universes: if we don’t hear their perspectives, they remain objects, if highly idealized objects in a male gaze way past its “best by” date. Women also love passionately, we know that. I think of the women who are open and persistent about their desires in Thambikku endha ooru (1984), Paruthiveeran (2007), Maryan (2013) among others, to the extent that they annoy the objects of their affection.

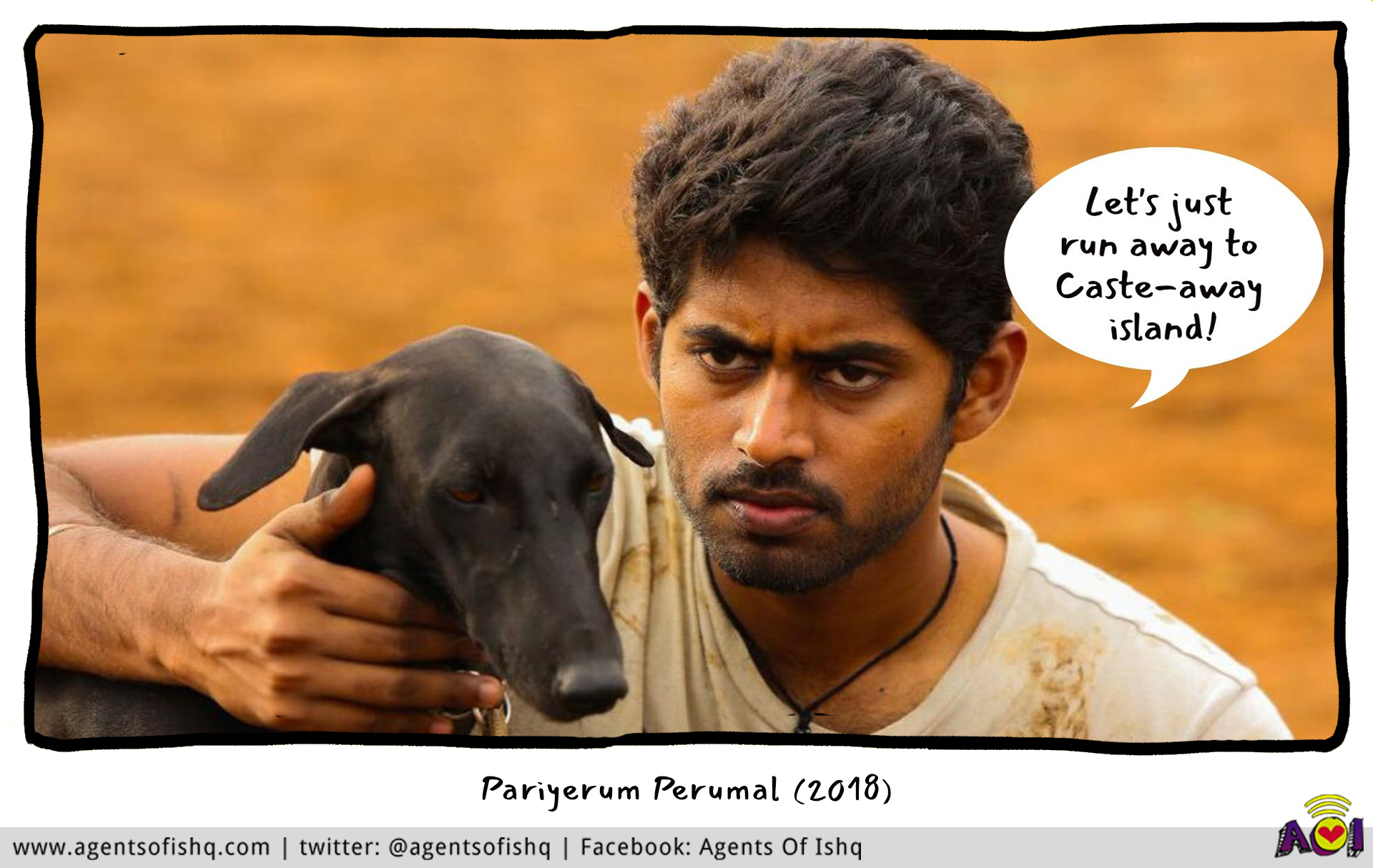

I like that only some of the men came around, much like in real life. Women frequently transgress propriety to pursue relationships with men out of bounds. In movies and in real life, they and the men (more so the men, when they are from the lower strata) pay tragic, huge prices when they do so (Kaadhal (2004), Pariyerum Perumal (2018)).

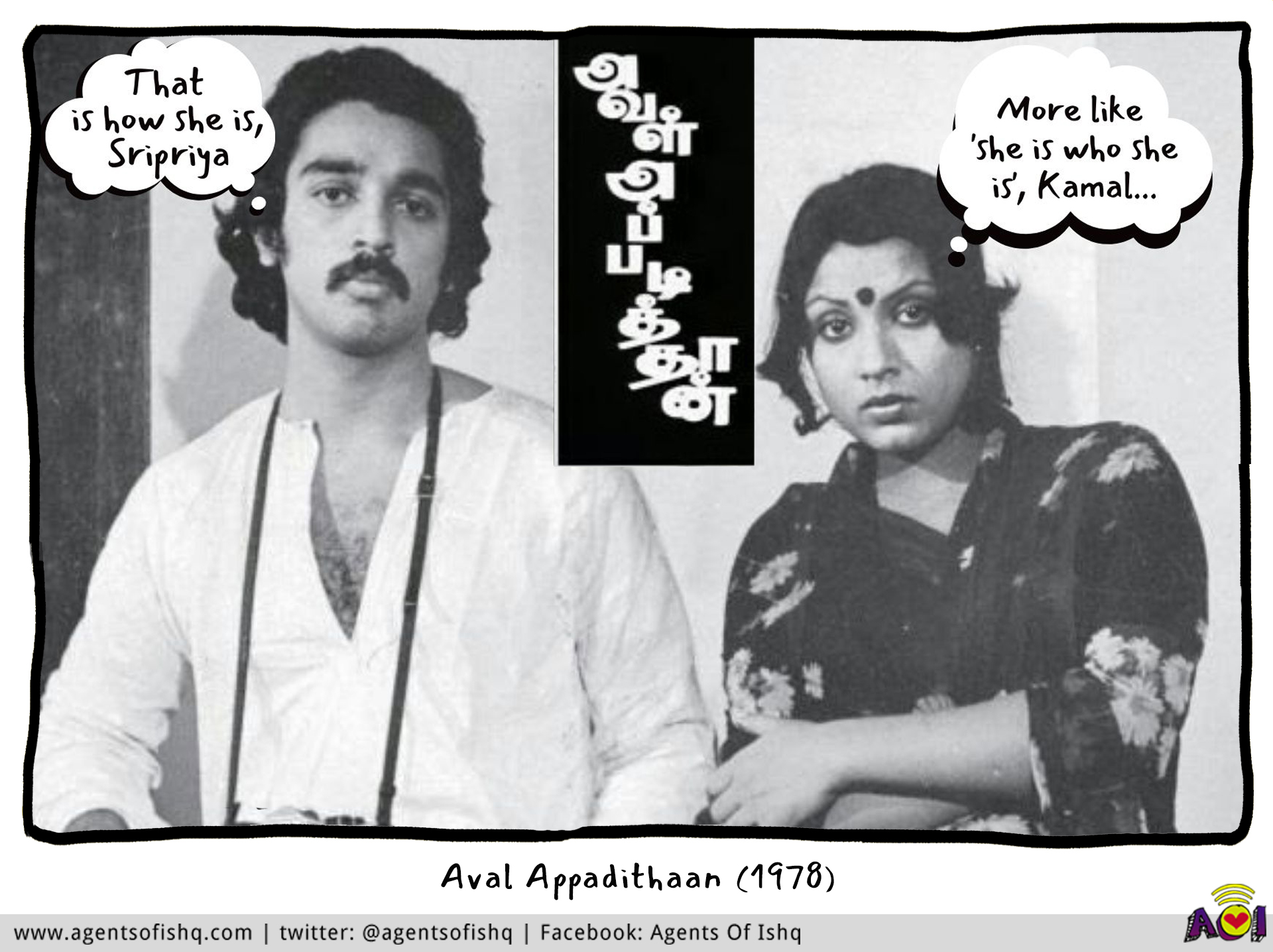

I like that only some of the men came around, much like in real life. Women frequently transgress propriety to pursue relationships with men out of bounds. In movies and in real life, they and the men (more so the men, when they are from the lower strata) pay tragic, huge prices when they do so (Kaadhal (2004), Pariyerum Perumal (2018)).  Women have interesting perspectives too, and live to tell them: caste rejects them too. To stumble through their pursuit of romantic love and companionship: surely that’s not a privilege reserved for men? Women also have flawed choices and difficult circumstances to heal from. They sometimes want the things society tells them they should have; if only they weren’t always made to feel like complete failures for not succeeding. They often try to parse their own desires from societal conditioning, all the while wondering if that is even possible to do. They look for their truths and try to live authentically by them, as a result, remaining stubborn and “stuck” in the eyes of others. There are women who refuse marriage, while longing for either their Karthik or just companionship in general, on their own terms. There are others who enter marriages and partnerships, and choose to exit them, both for simple and complex reasons. These are real struggles faced by lone women, some of them mine, others of women I know, which I wish we saw more of. Instead, Kaatru Veliyidai (2017), say, trains its eye on the male lead and his supposed redemption for being an abusive boyfriend, while Leela is raising a child on her own for years, which we see nothing of. I wonder if Aval Appadithaan (meaning “that is how she is” in Tamil; 1978) is the golden standard, for featuring a single woman who was a source of anxiety both to herself and those around her, with her unaddressed baggage, conflicting desires and relentless swimming against the tide.

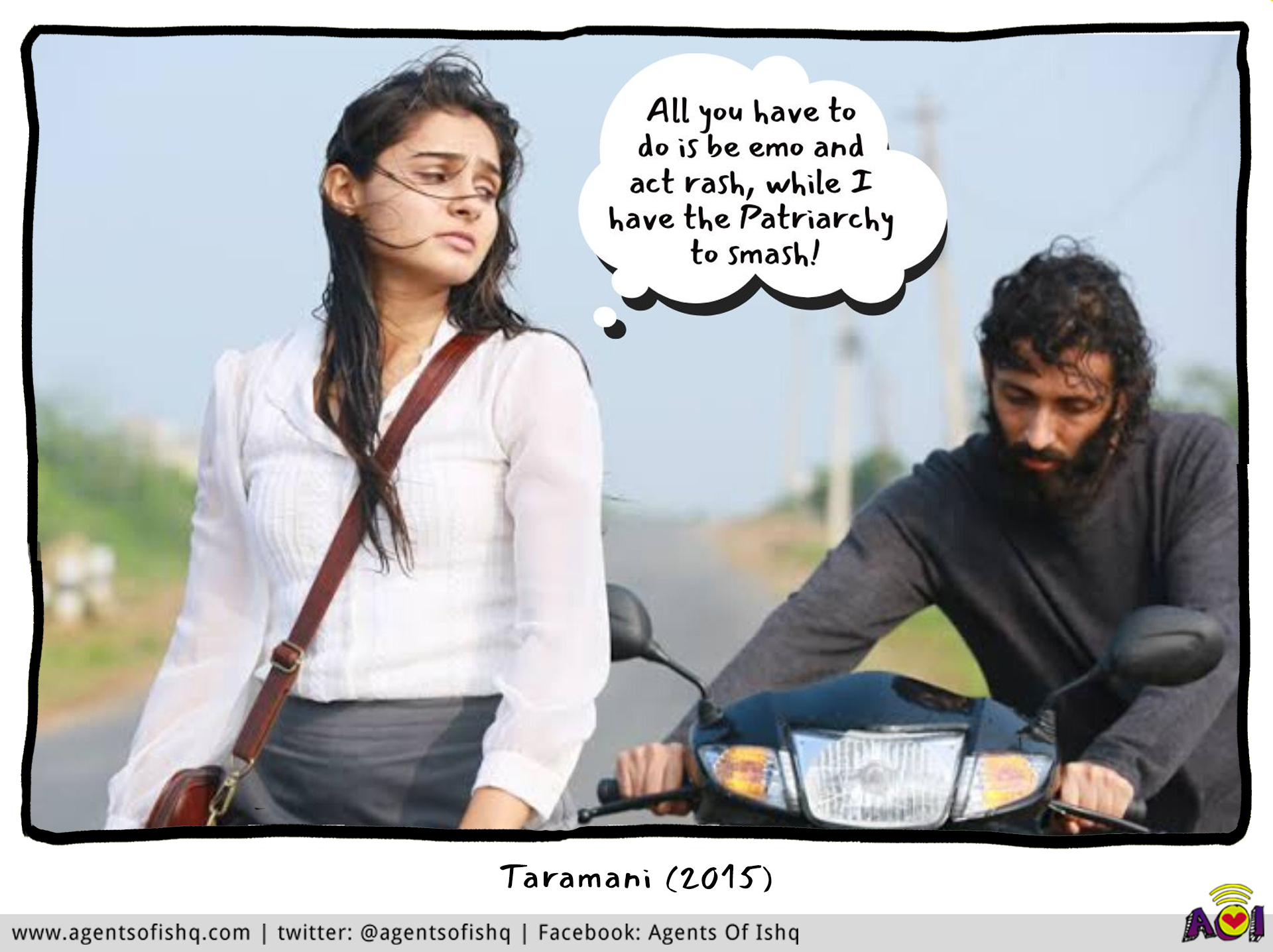

Women have interesting perspectives too, and live to tell them: caste rejects them too. To stumble through their pursuit of romantic love and companionship: surely that’s not a privilege reserved for men? Women also have flawed choices and difficult circumstances to heal from. They sometimes want the things society tells them they should have; if only they weren’t always made to feel like complete failures for not succeeding. They often try to parse their own desires from societal conditioning, all the while wondering if that is even possible to do. They look for their truths and try to live authentically by them, as a result, remaining stubborn and “stuck” in the eyes of others. There are women who refuse marriage, while longing for either their Karthik or just companionship in general, on their own terms. There are others who enter marriages and partnerships, and choose to exit them, both for simple and complex reasons. These are real struggles faced by lone women, some of them mine, others of women I know, which I wish we saw more of. Instead, Kaatru Veliyidai (2017), say, trains its eye on the male lead and his supposed redemption for being an abusive boyfriend, while Leela is raising a child on her own for years, which we see nothing of. I wonder if Aval Appadithaan (meaning “that is how she is” in Tamil; 1978) is the golden standard, for featuring a single woman who was a source of anxiety both to herself and those around her, with her unaddressed baggage, conflicting desires and relentless swimming against the tide.  More recently, Althea of Taramani (2015), a drama about two opposites finding, losing, and ultimately re-finding each other, came close. Watching her navigate the (perhaps disproportionate) patriarchy in her personal and professional relationships, second-guess decisions that simultaneously free her and cost her (ouch, so close to the bone!), and just about manage to keep her life together – all while the man goes on a bizarre, toxic rampage against multiple women in his hurt - was deeply satisfying. That Althea even has a job and needs to work is a relief.

More recently, Althea of Taramani (2015), a drama about two opposites finding, losing, and ultimately re-finding each other, came close. Watching her navigate the (perhaps disproportionate) patriarchy in her personal and professional relationships, second-guess decisions that simultaneously free her and cost her (ouch, so close to the bone!), and just about manage to keep her life together – all while the man goes on a bizarre, toxic rampage against multiple women in his hurt - was deeply satisfying. That Althea even has a job and needs to work is a relief.  Which brings me to my other big beef:

Which brings me to my other big beef:

What do these women do? What do they care about?

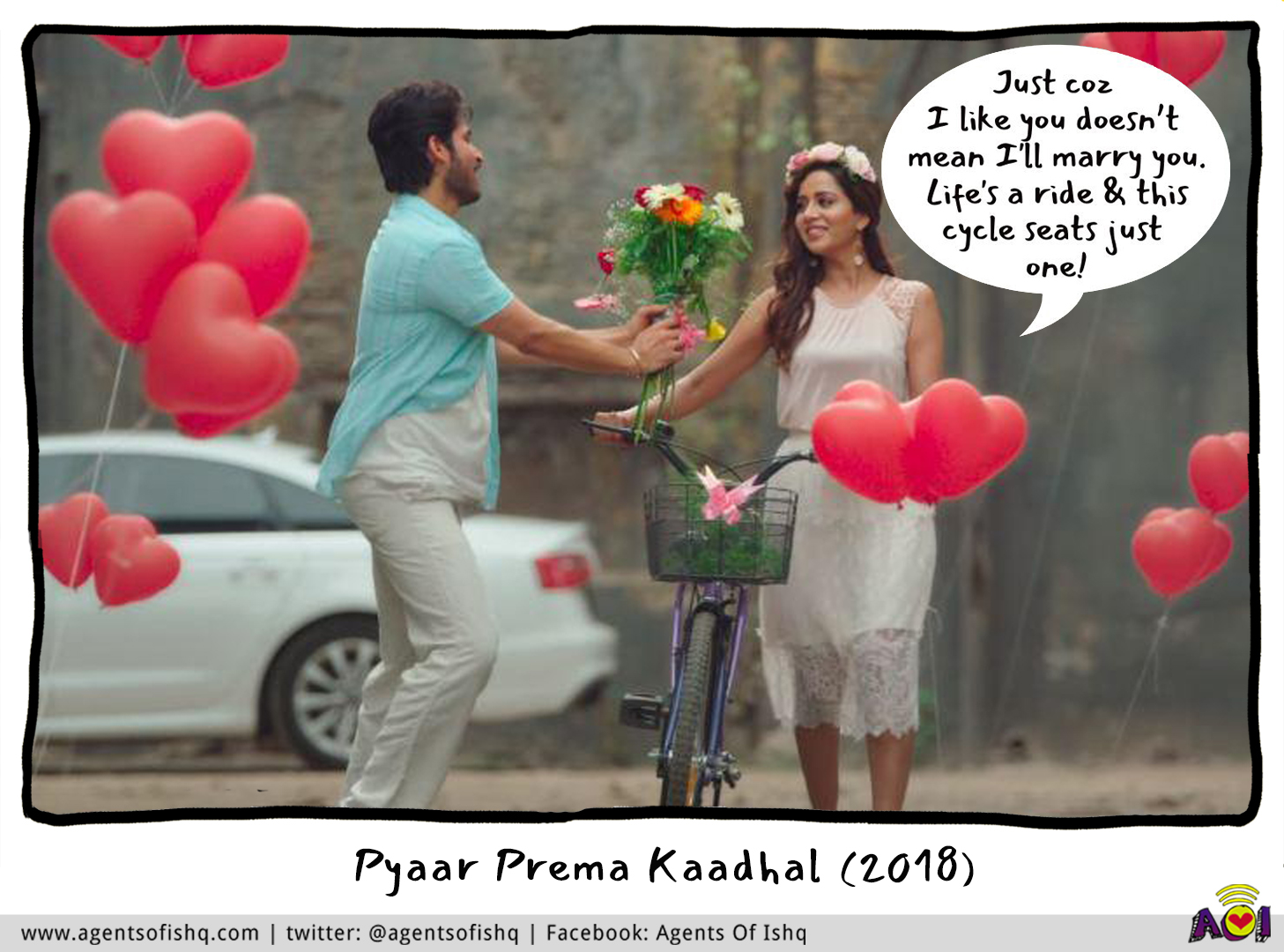

I am not the first one to ask this question, I won’t be the last. The women protagonists in K Balachander movies of the 1970s and 80s found themselves forced to provide for their families, and this very compulsion and a seemingly endless volley of setbacks cost their romantic lives dearly (Arangetram, Aval Oru Thodarkathai, Manadhil Urudhi Vendum). Women who actually had to care about their jobs, families and love have since largely disappeared. The angsty male artist iterations of the soup boy in recent times have not one, but two passions: a woman, and a creative pursuit. (“Passionate” people do indeed often have more than one passion!) Women too have careers, projects, art, and radical pursuits they care deeply about and want to succeed at. We also persevere with determination, and not just within paradigms of heteronormative marriages like the long-suffering wives in many a movie. We succeed at some things, and fail at others. Many of us hustle alone in our full lives on a day-to-day basis, going to work, fixing our homes, lifting suitcases, moving multiple times, cooking for one, trying new things, managing our minds and bodies, caring for loved ones, and climbing into cold beds by ourselves at the average day’s end whether that day was good or terrible, our COVID lives not that different from life otherwise. Where are these stories? I appreciated that Sindhuja walked away from an otherwise fulfilling partnership for fear that marriage would clip her professional wings in Pyaar Prema Kaadhal (2018); I would’ve liked more of her. Yashoda of Sillu Karupatti (2019) deserves her own full-length movie.  Yeah right. It remains hard enough to find a Tamil heroine who looks Tamil and speaks Tamil, and here I am, asking for the impossible, eh? I do have a note of appreciation, Bollywood-side in this case, specifically for Tara in Heer toh badi sad hai. Tamasha (2015), the movie this song features in, was rightfully called out for going down the overdone girl-as-muse to awaken the guy-as-creative-genius road for a mostly boring three hours. But this song is a rousing four minutes with so much good. Tara loves ardently and impractically, and is rewarded with a life of considerable loneliness for it. She has a job, and remains good at it, getting promotions along the way. She enjoys her comics, music, and the birthday cake she has presumably bought or baked for herself, that she will cut and eat by herself (yes, no sharing). She dresses up to go out, then comes back home and dances like no one is watching, because no one is. She pines, sometimes with a tiny smile on her face. That looks authentic to me, the existence of a practical life where skills are used, bills get paid, and fun is had, alongside a gnawing emptiness that seems just a little bit bigger than anything she tries to plug it with. There is longing and sadness, but without unrelenting tragedy; they sit alongside joy, self-reliance, and hope. The song identifies a truth: that it is indeed possible to be “happy sad,” and single. (Women don’t have to turn into vicious Neelambaris as a result of being unfulfilled.)

Yeah right. It remains hard enough to find a Tamil heroine who looks Tamil and speaks Tamil, and here I am, asking for the impossible, eh? I do have a note of appreciation, Bollywood-side in this case, specifically for Tara in Heer toh badi sad hai. Tamasha (2015), the movie this song features in, was rightfully called out for going down the overdone girl-as-muse to awaken the guy-as-creative-genius road for a mostly boring three hours. But this song is a rousing four minutes with so much good. Tara loves ardently and impractically, and is rewarded with a life of considerable loneliness for it. She has a job, and remains good at it, getting promotions along the way. She enjoys her comics, music, and the birthday cake she has presumably bought or baked for herself, that she will cut and eat by herself (yes, no sharing). She dresses up to go out, then comes back home and dances like no one is watching, because no one is. She pines, sometimes with a tiny smile on her face. That looks authentic to me, the existence of a practical life where skills are used, bills get paid, and fun is had, alongside a gnawing emptiness that seems just a little bit bigger than anything she tries to plug it with. There is longing and sadness, but without unrelenting tragedy; they sit alongside joy, self-reliance, and hope. The song identifies a truth: that it is indeed possible to be “happy sad,” and single. (Women don’t have to turn into vicious Neelambaris as a result of being unfulfilled.)

Sure, the song features a heroine who looks like that. She doesn’t seem to have to care for or support anyone or anything but herself (although I’ll admit there’s a part of me that is gratified to see her enjoy the privileges of self-absorption). She seems to have no close friends, which has to be the most baffling bit. I would throw in at least one, if not a whole crew of smart, supportive, spiritual sisters, navigating their own complex lives and passions alongside. (Soup boys always get a bunch of sympathetic drunk boys to commiserate with!) I wish we knew more about her job; she herself doesn’t seem particularly excited by it. But, but, this is more than I’ve had in so many movies. A shout-out also to Yazhini of Kadhalum Kadandhu Pogum (2016), who only seems to care about her independence and career, figuring out life on her own in the big city, until the man appears, only to help her get what she wants: a rare inversion of what women get to do in the movies. Even the movie is unsure if the leads are actually romantically involved.

Of many kinds of love

You could say this piece so far is guilty of the same thing as Tamil cinema: a singular preoccupation with romantic love. I suspect it is because of who I am and where I am at, a cis, straight, privileged-in-every-way woman in her early thirties, deliberating a whole lot on romantic love. As journalist and single woman Kalpana Sharma points out, some of us do spend many years assuming that marriage is indeed inevitable. Even as I draw a great deal of my self-worth from being fiercely independent, confronting the possibility of perhaps never finding romantic fulfillment or a long-term partnership, and aging alone in a society that doesn’t always offer support structures remains scary. However, while acknowledging that “single” is an unstable status, the truth is that contentment is possible as a single woman; marriage is indeed only one option. I think of the scores of women, socioeconomic status notwithstanding, who make the intentional, political choice to be single, a way of resisting the oppressions that heterosexual partnerships can impose on women. I learn about the Ekal Nari Shakti Sangathan that works against sexual harassment and caste norms against single women, while enabling property rights and alternate possibilities. I myself work with more than a dozen badass radical women, many of them single, who persevere every day to create more equitable communities and cities and lead very meaningful lives. I remind myself of the expansive love ethic bell hooks teaches us about, which I strive to practice in my own life, to deepen connection with people and nature, build community, work for justice, and forgive and accept myself as I am, imperfect, much like my life. I want these stories told on screen. I want more stories about womxn, their complicated desires, and all the possibilities in their lives, many of which I don’t see yet, and could really use. I trust Nayanthara to enable some, like she did with Aramm (2017) and Kolamaavu Kokila (2018). (Romantic love, what’s that?) I want more stories told by womxn. May we never settle.