At a friend’s place, two gin and tonics down, senses lulled enough to float through the space of the unsaid, the unbidden, legs stretched out on the blue couch, faintly dusted with dog and cat hair, feet being massaged by another friend as she scolds me for how tight my feet are, and into that space, that oasis of silence, she asks me, “Do you think in an alternate universe, Neha and you might have been lovers?”It comes like a comet streaking across the sky, the tail bright and beautiful – not the thought, no, I have heard this line so many times in the 21 years of knowing and loving Neha – but the idea, momentarily slicing through my sky, but not wounding, the idea of an alternate universe where perhaps love could be defined in another way; that idea was electrifying.***I have always wondered, what does it mean to be in love? What separates the idea of love from friendship? Does it always have to be reduced to a potent concentrate of physicality and sexuality, that can then, over time, be diluted with water to taste?We are a country where it isn’t uncommon to see friends of the same sex holding hands and walking down the road, their bodies plastered to each other as they go zipping down the roads in their motorbikes and scooters – even as gay rights and acceptance continue to inhabit an uneasy space.I grew up like most people with the binaries of gender and identity, where discovering who you were was intrinsically tied to how and who we love. Anything that fell in between, that inchoate space of friendship and love, was to be quickly categorised or swiftly denied. It is the binaries that exist in hushed whispers, as if uttering them somehow wakes up the slumbering air of gossip – “You are acting like you are obsessed, Neha. You need to stop talking to her for a week, do it like a test, to see if you can.” “Who do you love more? Me or Neha? This is not feeling like a normal friendship to me.” “Look at them, they are like girlfriend and boyfriend. It’s gross.”*** I met her in college. She was one year my junior, though we are of the same age (I don’t know why I feel compelled to state this). We were both pursuing a degree in English literature. The all-women college I was a part of, after 12 years of co-ed schooling, felt oddly refreshing, liberating even, this lack of male attention. We had a newly-introduced credit system, the choice of electives to make up the credits mostly like a pond of rubber ducks, open to both first and second year students. I was stuck with rubber duck exhibit 29 – biology. Ten minutes after class began and we had all settled in, Neha walked in. Short hair, cut close to the head, black jeans, and a long, oversized checked shirt over a T-shirt underneath, making her look shorter than she was, rounder than she was, a tall guitar case slung across her shoulder, round glasses and a mole on her face. She almost looked like a boy. She sat right in front.That same afternoon, I saw her at the auditions for the Western Music Club. I was already part of the Light Music Club. In Madras, the term 'Light Music' is used to define the music from our movies. To denote that which is obviously different from the heavier classical repertoire of Carnatic/Hindustani music, the notes settling around your feet like cement, demanding your full and complete attention. Light Music, on the other hand, was a lot more generous, a lot more lenient. You could commit the sacrilege of walking away half way.I auditioned with Celine Dion’s ‘My heart will go on’, a song already scratchy from the number of times I had listened to it on my Walkman. I was not selected. Neha, though, had been selected.Somewhere between my second year and her first year, we met. Properly. “Have you heard Neha play the guitar and sing? Oh you must!” And so, led by other friends, I made my way to her music, at break time, outside the canteen area, under the big Banyan tree, that later she would teach me to climb, holding my hand, guiding my step. I discovered the warmth of her hands. I also discovered Simon and Garfunkel, CSNY, Cat Stevens, Bread, and so many others through her.Somewhere between my third year and her second year, when she became the president of the Western Music club and I was finally selected (ha!), we spent countless hours of rehearsals in her house, as a group and alone, when I learnt to play the guitar - she the tutor, me the student - when I spent nights in her house - the two of us sharing a blanket, looking at the glow worms and stars and moon stuck on her ceiling, sharing stories of family, of history, of grief, of pain and love - when I melded into the rhythm of her life, her home, her family, when we couldn’t separate time spent together and time spent apart, somewhere between then, I became her music and she mine.***I rediscovered the art of letter-writing with Neha. We would write to each other constantly. Long letters. She still holds the record – 52 pages – front and back. But no, I did not fall asleep. I was swept into this world of antiquity and charm, of magic and make-believe, of finding letters snuck into post boxes or slipped under the door. When I left for Bombay, for my post-graduate diploma, the letters I received almost every week became my anchor against Bombay’s unforgiving harshness and the terrifying need to grow up. Amidst the thousands rushing to catch the train, I was just one more, being shoved and nudged and shoving and nudging in turn, and yet, I was different. I had Neha’s letters. In one of them she said, I am sending you a ‘musc grave’. When the letter came it had five dead mosquitoes stuck under transparent cello-tape. It was amusing then – we battle mosquitoes in Madras every monsoon, and countless mosquitoes are killed without second thought – but in retrospect it was an offering, a sacrifice of blood, seeping through the layers of devotion, of a friendship entering the nebulous space of love undefined. And so viscerally different from the other friendships in my life that, however close, never required or demanded so much of me.

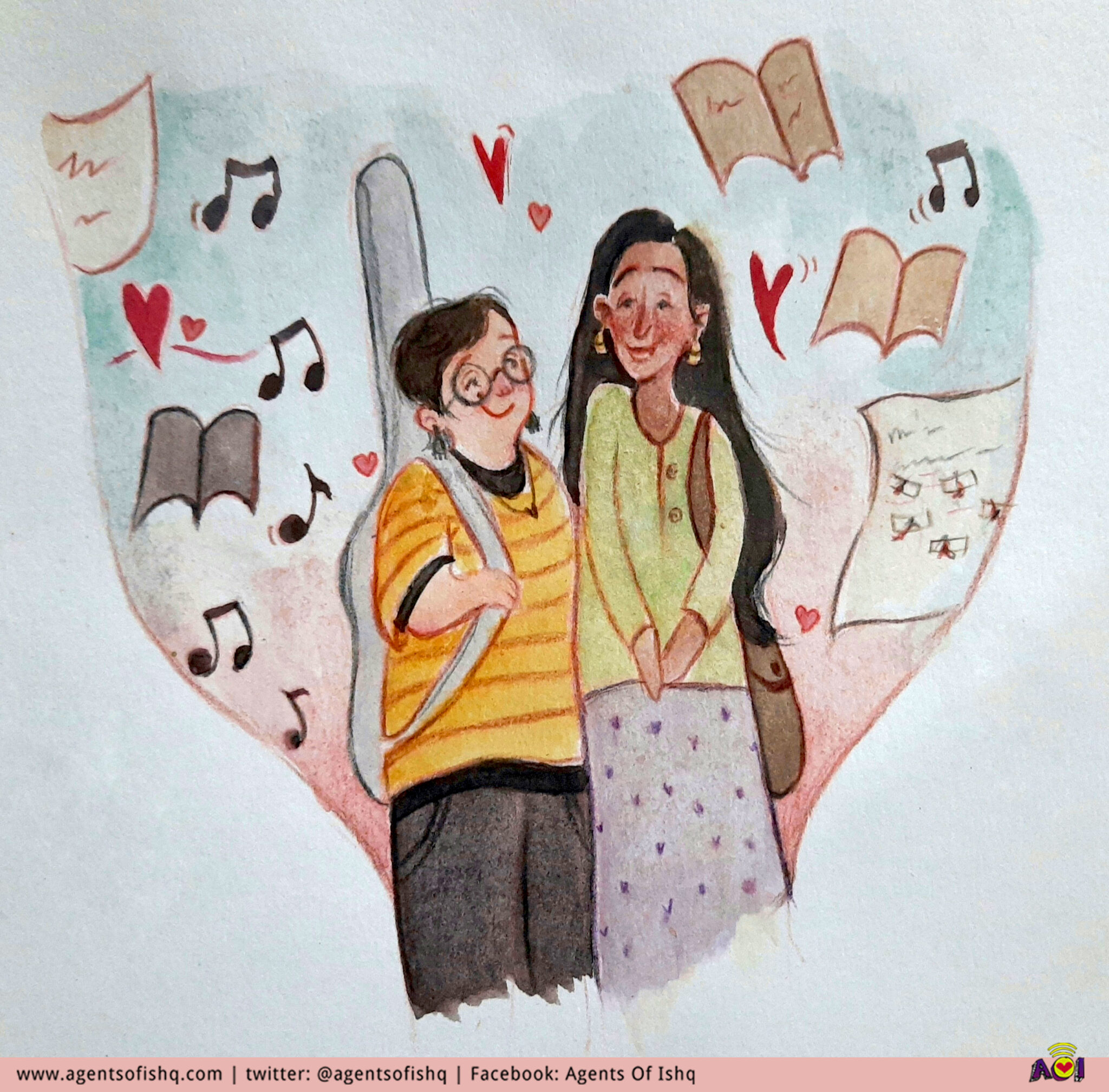

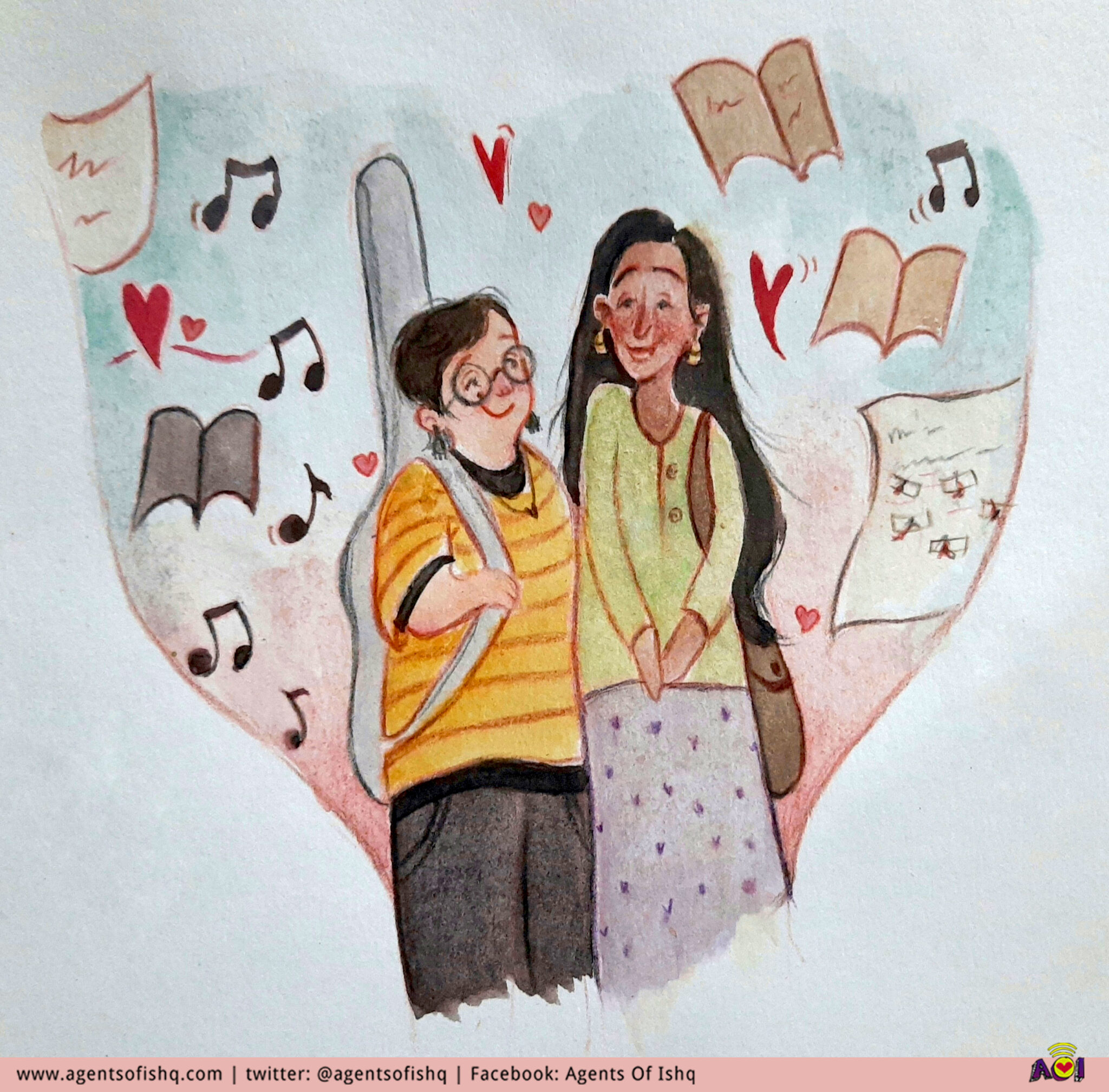

I met her in college. She was one year my junior, though we are of the same age (I don’t know why I feel compelled to state this). We were both pursuing a degree in English literature. The all-women college I was a part of, after 12 years of co-ed schooling, felt oddly refreshing, liberating even, this lack of male attention. We had a newly-introduced credit system, the choice of electives to make up the credits mostly like a pond of rubber ducks, open to both first and second year students. I was stuck with rubber duck exhibit 29 – biology. Ten minutes after class began and we had all settled in, Neha walked in. Short hair, cut close to the head, black jeans, and a long, oversized checked shirt over a T-shirt underneath, making her look shorter than she was, rounder than she was, a tall guitar case slung across her shoulder, round glasses and a mole on her face. She almost looked like a boy. She sat right in front.That same afternoon, I saw her at the auditions for the Western Music Club. I was already part of the Light Music Club. In Madras, the term 'Light Music' is used to define the music from our movies. To denote that which is obviously different from the heavier classical repertoire of Carnatic/Hindustani music, the notes settling around your feet like cement, demanding your full and complete attention. Light Music, on the other hand, was a lot more generous, a lot more lenient. You could commit the sacrilege of walking away half way.I auditioned with Celine Dion’s ‘My heart will go on’, a song already scratchy from the number of times I had listened to it on my Walkman. I was not selected. Neha, though, had been selected.Somewhere between my second year and her first year, we met. Properly. “Have you heard Neha play the guitar and sing? Oh you must!” And so, led by other friends, I made my way to her music, at break time, outside the canteen area, under the big Banyan tree, that later she would teach me to climb, holding my hand, guiding my step. I discovered the warmth of her hands. I also discovered Simon and Garfunkel, CSNY, Cat Stevens, Bread, and so many others through her.Somewhere between my third year and her second year, when she became the president of the Western Music club and I was finally selected (ha!), we spent countless hours of rehearsals in her house, as a group and alone, when I learnt to play the guitar - she the tutor, me the student - when I spent nights in her house - the two of us sharing a blanket, looking at the glow worms and stars and moon stuck on her ceiling, sharing stories of family, of history, of grief, of pain and love - when I melded into the rhythm of her life, her home, her family, when we couldn’t separate time spent together and time spent apart, somewhere between then, I became her music and she mine.***I rediscovered the art of letter-writing with Neha. We would write to each other constantly. Long letters. She still holds the record – 52 pages – front and back. But no, I did not fall asleep. I was swept into this world of antiquity and charm, of magic and make-believe, of finding letters snuck into post boxes or slipped under the door. When I left for Bombay, for my post-graduate diploma, the letters I received almost every week became my anchor against Bombay’s unforgiving harshness and the terrifying need to grow up. Amidst the thousands rushing to catch the train, I was just one more, being shoved and nudged and shoving and nudging in turn, and yet, I was different. I had Neha’s letters. In one of them she said, I am sending you a ‘musc grave’. When the letter came it had five dead mosquitoes stuck under transparent cello-tape. It was amusing then – we battle mosquitoes in Madras every monsoon, and countless mosquitoes are killed without second thought – but in retrospect it was an offering, a sacrifice of blood, seeping through the layers of devotion, of a friendship entering the nebulous space of love undefined. And so viscerally different from the other friendships in my life that, however close, never required or demanded so much of me. A year later, I would violently shun this as another intense relationship would take hold of my life – the clearly defined “lover” relationship – and I would let Neha go (she’s never even had a crush, what does she know about love?). Not gracefully, of course not. But with the anger of an avenging tribal chief – my swords were out, my armour in place, my eyes blazing, my words a rain of pins. The onslaught was brutal, I couldn’t control it. Stormy phone conversations; loud bangs of the then-landline phone; directed, deliberate and furious silences when in a group gathering, making everyone uncomfortable; and a constant need to attack. It was confusing, because I never knew what it was I was fighting – my own incapability of rising beyond definitions (who is Neha, now that I have a boyfriend?) or my inability to fully succumb to them?It felt like ancient anger, the other side of unconditional love, the depths of an almost satanic urge to see how far she would go in her love, how far would I go in my anger, and would we come out the other side? Friendship often accords that exit card; the stakes are never high enough and the platitudes many – things change, it is natural to drift apart, when life takes over, it’s hard to maintain close friendships, we picked up exactly where we left off – unlike a lover who would demand redemption – if you love me, you will forgive me.It was like I was standing on a far-away mountain watching Neha try and build a bridge from the opposite end, somewhere deeply relieved that she was willing to cross the rapidly growing chasm, but also, unable to stop myself from burning it down each time.Years later, in between her marriage and my divorce, we would talk about this several times over, and I would ask her what made her stay, she would simply say, “because I love you.” In her forgiveness I would find myself again.***Soon after we met in college, we went on our first Turtle Walk along the Besant Nagar beach, where turtle conservationists take a small group of people for a walk under the moonlight to save turtle nests from poachers. Neha had brought her guitar along, and on one of the rest stops along the way, she would play her music. Once we reached the hatchery, a good four hours later, we would all spread our sheets on the sand and fall asleep, waking up to a stunning sunrise marred by bums along the shore taking a shit.That morning, still heady from the salt and sand in our souls, we decided to walk back home, about six kilometres. At 6:30 am, after a quick tea from a roadside tea stall with very questionable teacups, we began walking, the roads relatively empty. Half-hour later, still nowhere close to home, the traffic surging past us, I can’t remember what it is we talked about, or even the exhaustion of the walk under Madras’ relentless sun, taking turns to carry the guitar, but I remember, as we neared my house, that we found a tree. The trunk of this tree was almost touching the ground before the branches pulled it up to meet the sky. We named this tree Lyd and the tree became, in many ways, the symbol of our friendship – we would return to it when we fought, or when we wanted to meet in between errands. But that first time, as we sat in a flushed silence, we felt that tingle of acceptance surge upward from the base of our spines, that blot of recognition spreading into an unrecognisable shape in our hearts – I see you and you see me – but we are not lovers. We did not inscribe our initials on that trunk. We did not need to.***During the Big Year of Separation, when I went to Bombay, Neha would surprise me with a five-day visit. She would sit in the playground on campus as I finished my classes and then we would take the bus or the train together to see not the sights that Bombay had to offer, but the paths I walked every day. When Neha left, and I went to drop her to the station, and we hugged outside, lingering just a bit longer, the auto-drivers around us would hoot. Maybe we were lovers – what they saw was a physical hug, but what we felt was the comfort of all of our silences that had and would punctuate our conversations, held together by two bodies.***

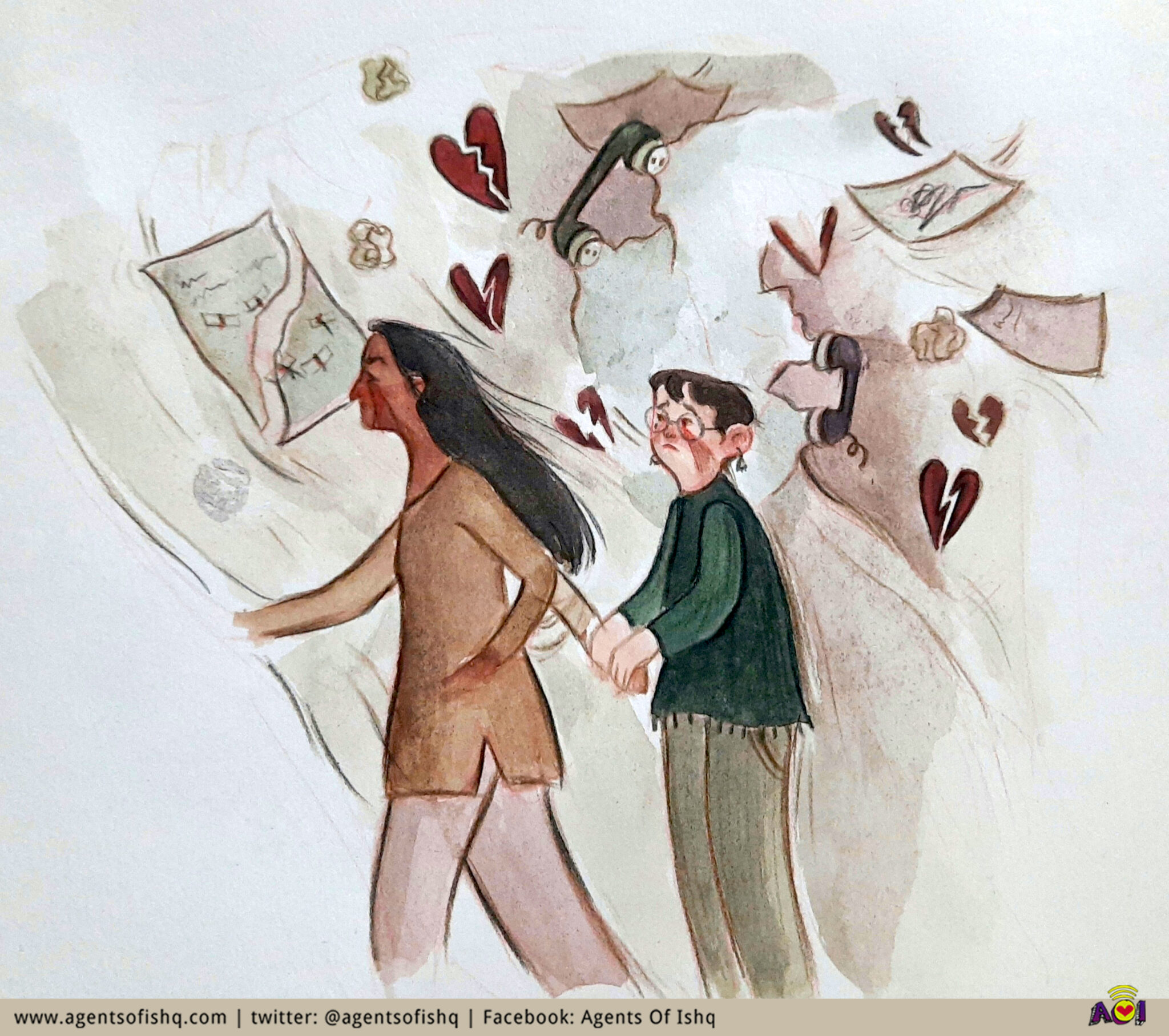

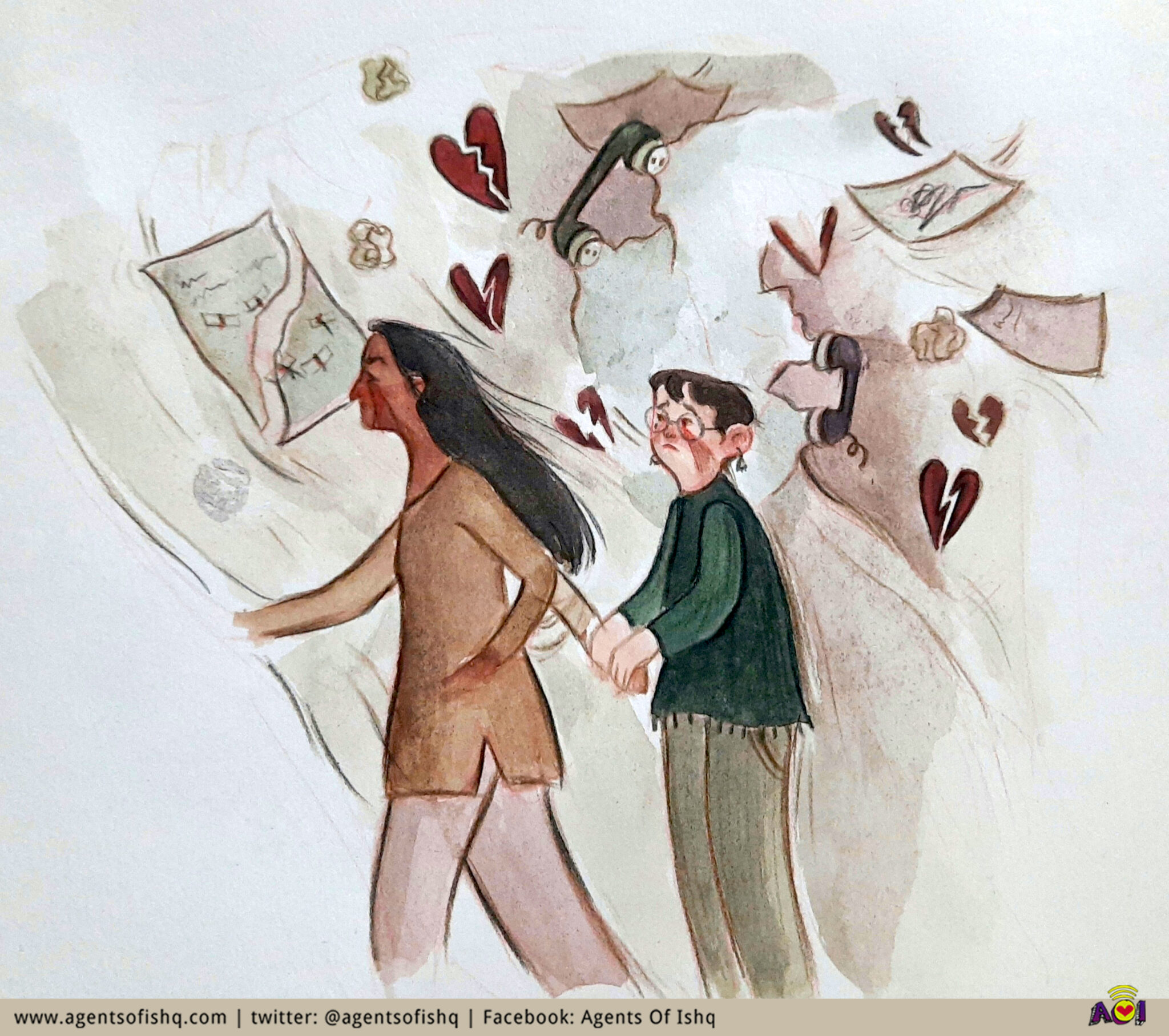

A year later, I would violently shun this as another intense relationship would take hold of my life – the clearly defined “lover” relationship – and I would let Neha go (she’s never even had a crush, what does she know about love?). Not gracefully, of course not. But with the anger of an avenging tribal chief – my swords were out, my armour in place, my eyes blazing, my words a rain of pins. The onslaught was brutal, I couldn’t control it. Stormy phone conversations; loud bangs of the then-landline phone; directed, deliberate and furious silences when in a group gathering, making everyone uncomfortable; and a constant need to attack. It was confusing, because I never knew what it was I was fighting – my own incapability of rising beyond definitions (who is Neha, now that I have a boyfriend?) or my inability to fully succumb to them?It felt like ancient anger, the other side of unconditional love, the depths of an almost satanic urge to see how far she would go in her love, how far would I go in my anger, and would we come out the other side? Friendship often accords that exit card; the stakes are never high enough and the platitudes many – things change, it is natural to drift apart, when life takes over, it’s hard to maintain close friendships, we picked up exactly where we left off – unlike a lover who would demand redemption – if you love me, you will forgive me.It was like I was standing on a far-away mountain watching Neha try and build a bridge from the opposite end, somewhere deeply relieved that she was willing to cross the rapidly growing chasm, but also, unable to stop myself from burning it down each time.Years later, in between her marriage and my divorce, we would talk about this several times over, and I would ask her what made her stay, she would simply say, “because I love you.” In her forgiveness I would find myself again.***Soon after we met in college, we went on our first Turtle Walk along the Besant Nagar beach, where turtle conservationists take a small group of people for a walk under the moonlight to save turtle nests from poachers. Neha had brought her guitar along, and on one of the rest stops along the way, she would play her music. Once we reached the hatchery, a good four hours later, we would all spread our sheets on the sand and fall asleep, waking up to a stunning sunrise marred by bums along the shore taking a shit.That morning, still heady from the salt and sand in our souls, we decided to walk back home, about six kilometres. At 6:30 am, after a quick tea from a roadside tea stall with very questionable teacups, we began walking, the roads relatively empty. Half-hour later, still nowhere close to home, the traffic surging past us, I can’t remember what it is we talked about, or even the exhaustion of the walk under Madras’ relentless sun, taking turns to carry the guitar, but I remember, as we neared my house, that we found a tree. The trunk of this tree was almost touching the ground before the branches pulled it up to meet the sky. We named this tree Lyd and the tree became, in many ways, the symbol of our friendship – we would return to it when we fought, or when we wanted to meet in between errands. But that first time, as we sat in a flushed silence, we felt that tingle of acceptance surge upward from the base of our spines, that blot of recognition spreading into an unrecognisable shape in our hearts – I see you and you see me – but we are not lovers. We did not inscribe our initials on that trunk. We did not need to.***During the Big Year of Separation, when I went to Bombay, Neha would surprise me with a five-day visit. She would sit in the playground on campus as I finished my classes and then we would take the bus or the train together to see not the sights that Bombay had to offer, but the paths I walked every day. When Neha left, and I went to drop her to the station, and we hugged outside, lingering just a bit longer, the auto-drivers around us would hoot. Maybe we were lovers – what they saw was a physical hug, but what we felt was the comfort of all of our silences that had and would punctuate our conversations, held together by two bodies.*** On one of the many afternoons I spent at Neha’s after college, we came up with a secret world – Bob, we called it – so we could escape into it whenever we wanted to. We never gave it a definitive form then – we drew it like an amoeba – but 21 years later, I think that amoeba-shaped world managed to fit into this one, precisely because it had the ability to keep changing and growing.“Are you my sister, or my friend, or are you my ‘di’?” Neha’s daughter asks mine, in between a game they are playing. They are the same age, my daughter younger than Neha’s by two-and-a-half months. In Tamil, ‘di’ (pronounced ‘dee’) is a colloquial suffix added to the ends of sentences between female friends, like ‘bro’, and yet, like the language itself, it carries a complexity that mothers my tongue; this word between the Hindi dosti and yaari ; between the sky that can contain the nuance of every word uttered and the sky that can be relentless in its chaos of understanding.. My daughter replies with a laugh saying ‘I am your di’, and it strikes me that perhaps that is what Neha is to me as well. My di. Two letters that straddle the sides of friendship and love, like a fearless warrior, hands on her hips and legs splayed, unwavering eyes meeting the world and absolving it of its own disdain. Two letters that become the womb of nebulous meaning shielding us from the stubborn import of definitions. Two letters that did not need an alternate universe to survive in. After all, it could, in fact, birth new ones. Praveena Shivram is an independent writer based in Madras. You can read her work here: praveenashivram.com.

On one of the many afternoons I spent at Neha’s after college, we came up with a secret world – Bob, we called it – so we could escape into it whenever we wanted to. We never gave it a definitive form then – we drew it like an amoeba – but 21 years later, I think that amoeba-shaped world managed to fit into this one, precisely because it had the ability to keep changing and growing.“Are you my sister, or my friend, or are you my ‘di’?” Neha’s daughter asks mine, in between a game they are playing. They are the same age, my daughter younger than Neha’s by two-and-a-half months. In Tamil, ‘di’ (pronounced ‘dee’) is a colloquial suffix added to the ends of sentences between female friends, like ‘bro’, and yet, like the language itself, it carries a complexity that mothers my tongue; this word between the Hindi dosti and yaari ; between the sky that can contain the nuance of every word uttered and the sky that can be relentless in its chaos of understanding.. My daughter replies with a laugh saying ‘I am your di’, and it strikes me that perhaps that is what Neha is to me as well. My di. Two letters that straddle the sides of friendship and love, like a fearless warrior, hands on her hips and legs splayed, unwavering eyes meeting the world and absolving it of its own disdain. Two letters that become the womb of nebulous meaning shielding us from the stubborn import of definitions. Two letters that did not need an alternate universe to survive in. After all, it could, in fact, birth new ones. Praveena Shivram is an independent writer based in Madras. You can read her work here: praveenashivram.com.

I met her in college. She was one year my junior, though we are of the same age (I don’t know why I feel compelled to state this). We were both pursuing a degree in English literature. The all-women college I was a part of, after 12 years of co-ed schooling, felt oddly refreshing, liberating even, this lack of male attention. We had a newly-introduced credit system, the choice of electives to make up the credits mostly like a pond of rubber ducks, open to both first and second year students. I was stuck with rubber duck exhibit 29 – biology. Ten minutes after class began and we had all settled in, Neha walked in. Short hair, cut close to the head, black jeans, and a long, oversized checked shirt over a T-shirt underneath, making her look shorter than she was, rounder than she was, a tall guitar case slung across her shoulder, round glasses and a mole on her face. She almost looked like a boy. She sat right in front.That same afternoon, I saw her at the auditions for the Western Music Club. I was already part of the Light Music Club. In Madras, the term 'Light Music' is used to define the music from our movies. To denote that which is obviously different from the heavier classical repertoire of Carnatic/Hindustani music, the notes settling around your feet like cement, demanding your full and complete attention. Light Music, on the other hand, was a lot more generous, a lot more lenient. You could commit the sacrilege of walking away half way.I auditioned with Celine Dion’s ‘My heart will go on’, a song already scratchy from the number of times I had listened to it on my Walkman. I was not selected. Neha, though, had been selected.Somewhere between my second year and her first year, we met. Properly. “Have you heard Neha play the guitar and sing? Oh you must!” And so, led by other friends, I made my way to her music, at break time, outside the canteen area, under the big Banyan tree, that later she would teach me to climb, holding my hand, guiding my step. I discovered the warmth of her hands. I also discovered Simon and Garfunkel, CSNY, Cat Stevens, Bread, and so many others through her.Somewhere between my third year and her second year, when she became the president of the Western Music club and I was finally selected (ha!), we spent countless hours of rehearsals in her house, as a group and alone, when I learnt to play the guitar - she the tutor, me the student - when I spent nights in her house - the two of us sharing a blanket, looking at the glow worms and stars and moon stuck on her ceiling, sharing stories of family, of history, of grief, of pain and love - when I melded into the rhythm of her life, her home, her family, when we couldn’t separate time spent together and time spent apart, somewhere between then, I became her music and she mine.***I rediscovered the art of letter-writing with Neha. We would write to each other constantly. Long letters. She still holds the record – 52 pages – front and back. But no, I did not fall asleep. I was swept into this world of antiquity and charm, of magic and make-believe, of finding letters snuck into post boxes or slipped under the door. When I left for Bombay, for my post-graduate diploma, the letters I received almost every week became my anchor against Bombay’s unforgiving harshness and the terrifying need to grow up. Amidst the thousands rushing to catch the train, I was just one more, being shoved and nudged and shoving and nudging in turn, and yet, I was different. I had Neha’s letters. In one of them she said, I am sending you a ‘musc grave’. When the letter came it had five dead mosquitoes stuck under transparent cello-tape. It was amusing then – we battle mosquitoes in Madras every monsoon, and countless mosquitoes are killed without second thought – but in retrospect it was an offering, a sacrifice of blood, seeping through the layers of devotion, of a friendship entering the nebulous space of love undefined. And so viscerally different from the other friendships in my life that, however close, never required or demanded so much of me.

I met her in college. She was one year my junior, though we are of the same age (I don’t know why I feel compelled to state this). We were both pursuing a degree in English literature. The all-women college I was a part of, after 12 years of co-ed schooling, felt oddly refreshing, liberating even, this lack of male attention. We had a newly-introduced credit system, the choice of electives to make up the credits mostly like a pond of rubber ducks, open to both first and second year students. I was stuck with rubber duck exhibit 29 – biology. Ten minutes after class began and we had all settled in, Neha walked in. Short hair, cut close to the head, black jeans, and a long, oversized checked shirt over a T-shirt underneath, making her look shorter than she was, rounder than she was, a tall guitar case slung across her shoulder, round glasses and a mole on her face. She almost looked like a boy. She sat right in front.That same afternoon, I saw her at the auditions for the Western Music Club. I was already part of the Light Music Club. In Madras, the term 'Light Music' is used to define the music from our movies. To denote that which is obviously different from the heavier classical repertoire of Carnatic/Hindustani music, the notes settling around your feet like cement, demanding your full and complete attention. Light Music, on the other hand, was a lot more generous, a lot more lenient. You could commit the sacrilege of walking away half way.I auditioned with Celine Dion’s ‘My heart will go on’, a song already scratchy from the number of times I had listened to it on my Walkman. I was not selected. Neha, though, had been selected.Somewhere between my second year and her first year, we met. Properly. “Have you heard Neha play the guitar and sing? Oh you must!” And so, led by other friends, I made my way to her music, at break time, outside the canteen area, under the big Banyan tree, that later she would teach me to climb, holding my hand, guiding my step. I discovered the warmth of her hands. I also discovered Simon and Garfunkel, CSNY, Cat Stevens, Bread, and so many others through her.Somewhere between my third year and her second year, when she became the president of the Western Music club and I was finally selected (ha!), we spent countless hours of rehearsals in her house, as a group and alone, when I learnt to play the guitar - she the tutor, me the student - when I spent nights in her house - the two of us sharing a blanket, looking at the glow worms and stars and moon stuck on her ceiling, sharing stories of family, of history, of grief, of pain and love - when I melded into the rhythm of her life, her home, her family, when we couldn’t separate time spent together and time spent apart, somewhere between then, I became her music and she mine.***I rediscovered the art of letter-writing with Neha. We would write to each other constantly. Long letters. She still holds the record – 52 pages – front and back. But no, I did not fall asleep. I was swept into this world of antiquity and charm, of magic and make-believe, of finding letters snuck into post boxes or slipped under the door. When I left for Bombay, for my post-graduate diploma, the letters I received almost every week became my anchor against Bombay’s unforgiving harshness and the terrifying need to grow up. Amidst the thousands rushing to catch the train, I was just one more, being shoved and nudged and shoving and nudging in turn, and yet, I was different. I had Neha’s letters. In one of them she said, I am sending you a ‘musc grave’. When the letter came it had five dead mosquitoes stuck under transparent cello-tape. It was amusing then – we battle mosquitoes in Madras every monsoon, and countless mosquitoes are killed without second thought – but in retrospect it was an offering, a sacrifice of blood, seeping through the layers of devotion, of a friendship entering the nebulous space of love undefined. And so viscerally different from the other friendships in my life that, however close, never required or demanded so much of me. A year later, I would violently shun this as another intense relationship would take hold of my life – the clearly defined “lover” relationship – and I would let Neha go (she’s never even had a crush, what does she know about love?). Not gracefully, of course not. But with the anger of an avenging tribal chief – my swords were out, my armour in place, my eyes blazing, my words a rain of pins. The onslaught was brutal, I couldn’t control it. Stormy phone conversations; loud bangs of the then-landline phone; directed, deliberate and furious silences when in a group gathering, making everyone uncomfortable; and a constant need to attack. It was confusing, because I never knew what it was I was fighting – my own incapability of rising beyond definitions (who is Neha, now that I have a boyfriend?) or my inability to fully succumb to them?It felt like ancient anger, the other side of unconditional love, the depths of an almost satanic urge to see how far she would go in her love, how far would I go in my anger, and would we come out the other side? Friendship often accords that exit card; the stakes are never high enough and the platitudes many – things change, it is natural to drift apart, when life takes over, it’s hard to maintain close friendships, we picked up exactly where we left off – unlike a lover who would demand redemption – if you love me, you will forgive me.It was like I was standing on a far-away mountain watching Neha try and build a bridge from the opposite end, somewhere deeply relieved that she was willing to cross the rapidly growing chasm, but also, unable to stop myself from burning it down each time.Years later, in between her marriage and my divorce, we would talk about this several times over, and I would ask her what made her stay, she would simply say, “because I love you.” In her forgiveness I would find myself again.***Soon after we met in college, we went on our first Turtle Walk along the Besant Nagar beach, where turtle conservationists take a small group of people for a walk under the moonlight to save turtle nests from poachers. Neha had brought her guitar along, and on one of the rest stops along the way, she would play her music. Once we reached the hatchery, a good four hours later, we would all spread our sheets on the sand and fall asleep, waking up to a stunning sunrise marred by bums along the shore taking a shit.That morning, still heady from the salt and sand in our souls, we decided to walk back home, about six kilometres. At 6:30 am, after a quick tea from a roadside tea stall with very questionable teacups, we began walking, the roads relatively empty. Half-hour later, still nowhere close to home, the traffic surging past us, I can’t remember what it is we talked about, or even the exhaustion of the walk under Madras’ relentless sun, taking turns to carry the guitar, but I remember, as we neared my house, that we found a tree. The trunk of this tree was almost touching the ground before the branches pulled it up to meet the sky. We named this tree Lyd and the tree became, in many ways, the symbol of our friendship – we would return to it when we fought, or when we wanted to meet in between errands. But that first time, as we sat in a flushed silence, we felt that tingle of acceptance surge upward from the base of our spines, that blot of recognition spreading into an unrecognisable shape in our hearts – I see you and you see me – but we are not lovers. We did not inscribe our initials on that trunk. We did not need to.***During the Big Year of Separation, when I went to Bombay, Neha would surprise me with a five-day visit. She would sit in the playground on campus as I finished my classes and then we would take the bus or the train together to see not the sights that Bombay had to offer, but the paths I walked every day. When Neha left, and I went to drop her to the station, and we hugged outside, lingering just a bit longer, the auto-drivers around us would hoot. Maybe we were lovers – what they saw was a physical hug, but what we felt was the comfort of all of our silences that had and would punctuate our conversations, held together by two bodies.***

A year later, I would violently shun this as another intense relationship would take hold of my life – the clearly defined “lover” relationship – and I would let Neha go (she’s never even had a crush, what does she know about love?). Not gracefully, of course not. But with the anger of an avenging tribal chief – my swords were out, my armour in place, my eyes blazing, my words a rain of pins. The onslaught was brutal, I couldn’t control it. Stormy phone conversations; loud bangs of the then-landline phone; directed, deliberate and furious silences when in a group gathering, making everyone uncomfortable; and a constant need to attack. It was confusing, because I never knew what it was I was fighting – my own incapability of rising beyond definitions (who is Neha, now that I have a boyfriend?) or my inability to fully succumb to them?It felt like ancient anger, the other side of unconditional love, the depths of an almost satanic urge to see how far she would go in her love, how far would I go in my anger, and would we come out the other side? Friendship often accords that exit card; the stakes are never high enough and the platitudes many – things change, it is natural to drift apart, when life takes over, it’s hard to maintain close friendships, we picked up exactly where we left off – unlike a lover who would demand redemption – if you love me, you will forgive me.It was like I was standing on a far-away mountain watching Neha try and build a bridge from the opposite end, somewhere deeply relieved that she was willing to cross the rapidly growing chasm, but also, unable to stop myself from burning it down each time.Years later, in between her marriage and my divorce, we would talk about this several times over, and I would ask her what made her stay, she would simply say, “because I love you.” In her forgiveness I would find myself again.***Soon after we met in college, we went on our first Turtle Walk along the Besant Nagar beach, where turtle conservationists take a small group of people for a walk under the moonlight to save turtle nests from poachers. Neha had brought her guitar along, and on one of the rest stops along the way, she would play her music. Once we reached the hatchery, a good four hours later, we would all spread our sheets on the sand and fall asleep, waking up to a stunning sunrise marred by bums along the shore taking a shit.That morning, still heady from the salt and sand in our souls, we decided to walk back home, about six kilometres. At 6:30 am, after a quick tea from a roadside tea stall with very questionable teacups, we began walking, the roads relatively empty. Half-hour later, still nowhere close to home, the traffic surging past us, I can’t remember what it is we talked about, or even the exhaustion of the walk under Madras’ relentless sun, taking turns to carry the guitar, but I remember, as we neared my house, that we found a tree. The trunk of this tree was almost touching the ground before the branches pulled it up to meet the sky. We named this tree Lyd and the tree became, in many ways, the symbol of our friendship – we would return to it when we fought, or when we wanted to meet in between errands. But that first time, as we sat in a flushed silence, we felt that tingle of acceptance surge upward from the base of our spines, that blot of recognition spreading into an unrecognisable shape in our hearts – I see you and you see me – but we are not lovers. We did not inscribe our initials on that trunk. We did not need to.***During the Big Year of Separation, when I went to Bombay, Neha would surprise me with a five-day visit. She would sit in the playground on campus as I finished my classes and then we would take the bus or the train together to see not the sights that Bombay had to offer, but the paths I walked every day. When Neha left, and I went to drop her to the station, and we hugged outside, lingering just a bit longer, the auto-drivers around us would hoot. Maybe we were lovers – what they saw was a physical hug, but what we felt was the comfort of all of our silences that had and would punctuate our conversations, held together by two bodies.*** On one of the many afternoons I spent at Neha’s after college, we came up with a secret world – Bob, we called it – so we could escape into it whenever we wanted to. We never gave it a definitive form then – we drew it like an amoeba – but 21 years later, I think that amoeba-shaped world managed to fit into this one, precisely because it had the ability to keep changing and growing.“Are you my sister, or my friend, or are you my ‘di’?” Neha’s daughter asks mine, in between a game they are playing. They are the same age, my daughter younger than Neha’s by two-and-a-half months. In Tamil, ‘di’ (pronounced ‘dee’) is a colloquial suffix added to the ends of sentences between female friends, like ‘bro’, and yet, like the language itself, it carries a complexity that mothers my tongue; this word between the Hindi dosti and yaari ; between the sky that can contain the nuance of every word uttered and the sky that can be relentless in its chaos of understanding.. My daughter replies with a laugh saying ‘I am your di’, and it strikes me that perhaps that is what Neha is to me as well. My di. Two letters that straddle the sides of friendship and love, like a fearless warrior, hands on her hips and legs splayed, unwavering eyes meeting the world and absolving it of its own disdain. Two letters that become the womb of nebulous meaning shielding us from the stubborn import of definitions. Two letters that did not need an alternate universe to survive in. After all, it could, in fact, birth new ones. Praveena Shivram is an independent writer based in Madras. You can read her work here: praveenashivram.com.

On one of the many afternoons I spent at Neha’s after college, we came up with a secret world – Bob, we called it – so we could escape into it whenever we wanted to. We never gave it a definitive form then – we drew it like an amoeba – but 21 years later, I think that amoeba-shaped world managed to fit into this one, precisely because it had the ability to keep changing and growing.“Are you my sister, or my friend, or are you my ‘di’?” Neha’s daughter asks mine, in between a game they are playing. They are the same age, my daughter younger than Neha’s by two-and-a-half months. In Tamil, ‘di’ (pronounced ‘dee’) is a colloquial suffix added to the ends of sentences between female friends, like ‘bro’, and yet, like the language itself, it carries a complexity that mothers my tongue; this word between the Hindi dosti and yaari ; between the sky that can contain the nuance of every word uttered and the sky that can be relentless in its chaos of understanding.. My daughter replies with a laugh saying ‘I am your di’, and it strikes me that perhaps that is what Neha is to me as well. My di. Two letters that straddle the sides of friendship and love, like a fearless warrior, hands on her hips and legs splayed, unwavering eyes meeting the world and absolving it of its own disdain. Two letters that become the womb of nebulous meaning shielding us from the stubborn import of definitions. Two letters that did not need an alternate universe to survive in. After all, it could, in fact, birth new ones. Praveena Shivram is an independent writer based in Madras. You can read her work here: praveenashivram.com.