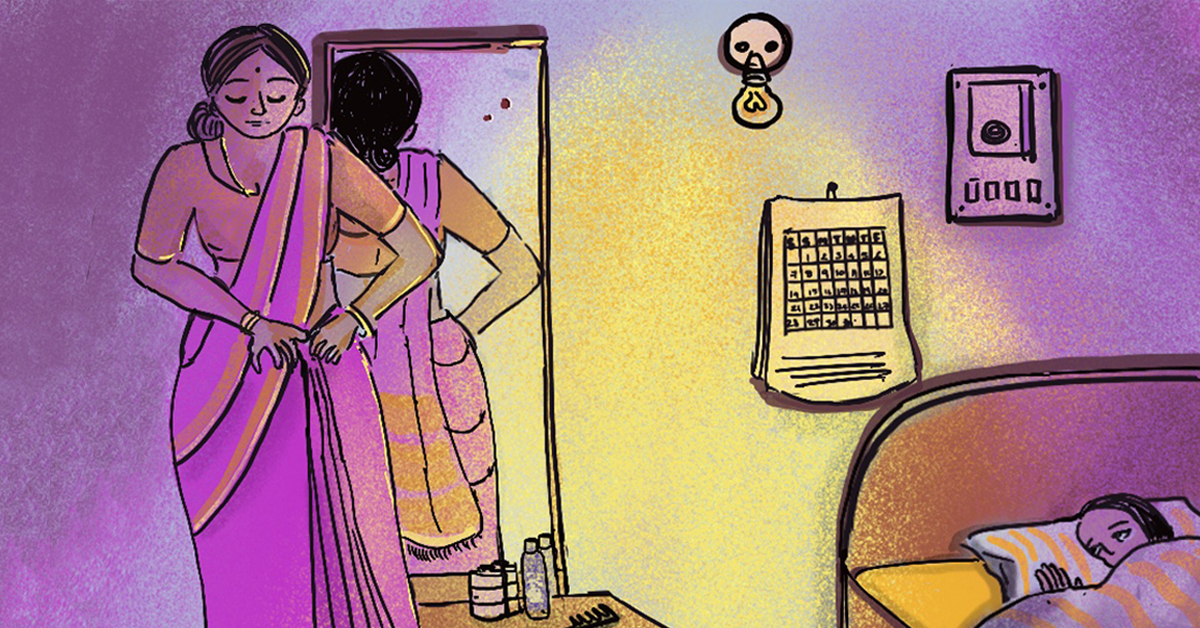

Amma used to drape me with her sarees.

It was the most observant I have been in everything she has tried to teach me and in hindsight, I felt if it was the pride of learning something in the first go. This would not happen often for me, and it made the activity of draping, wrapping, and wearing a saree a thrill.

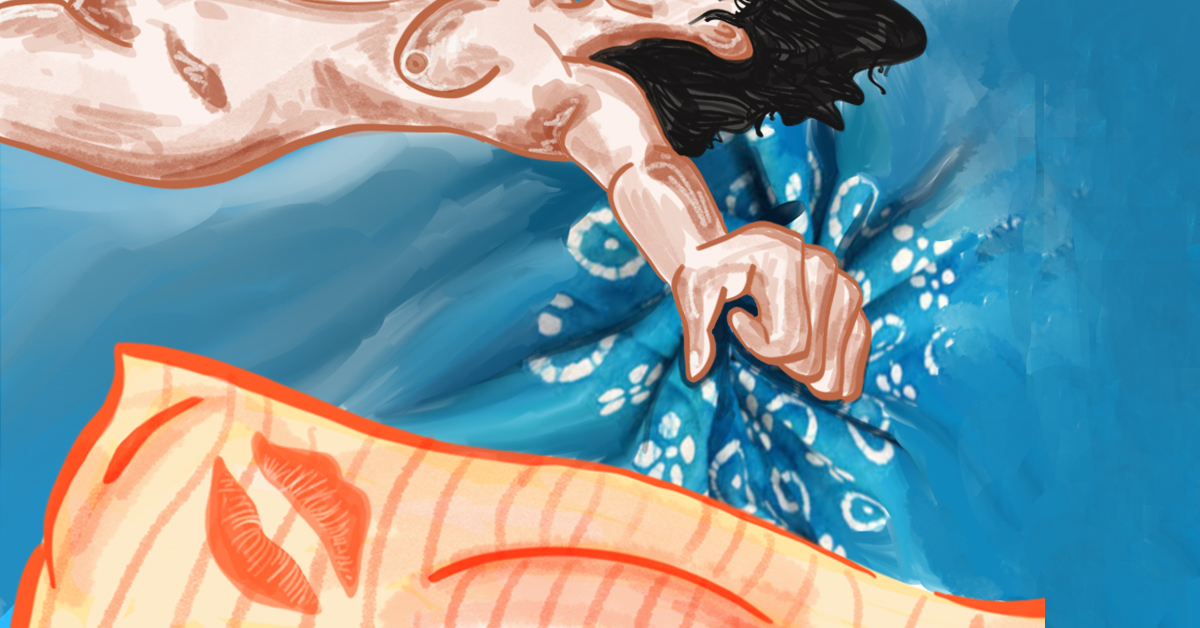

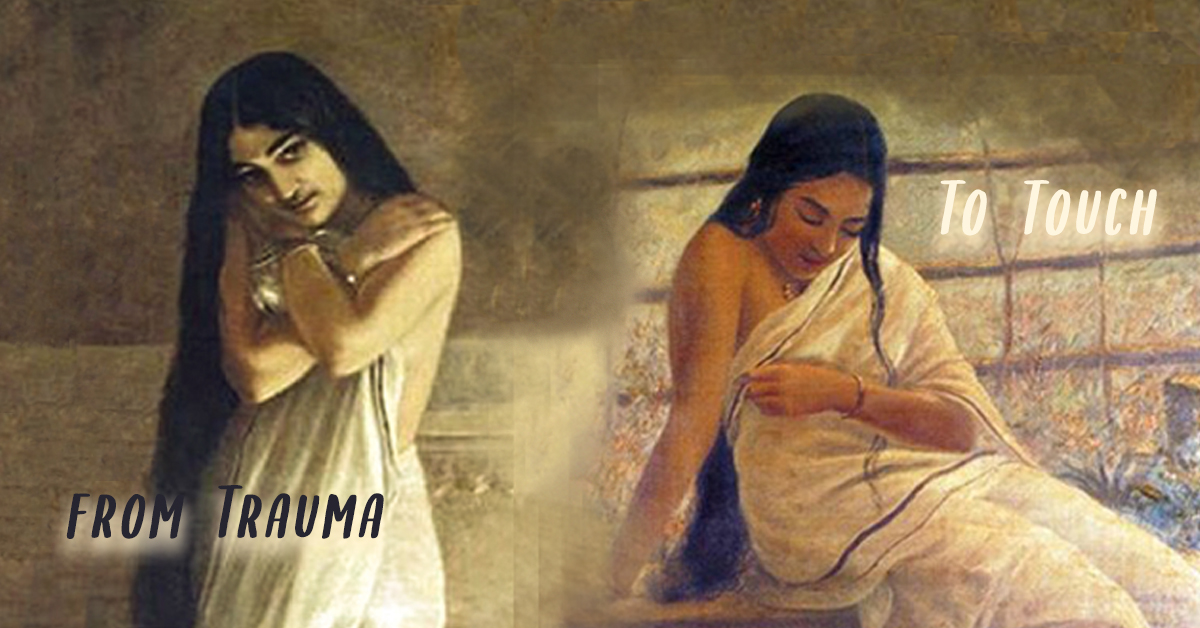

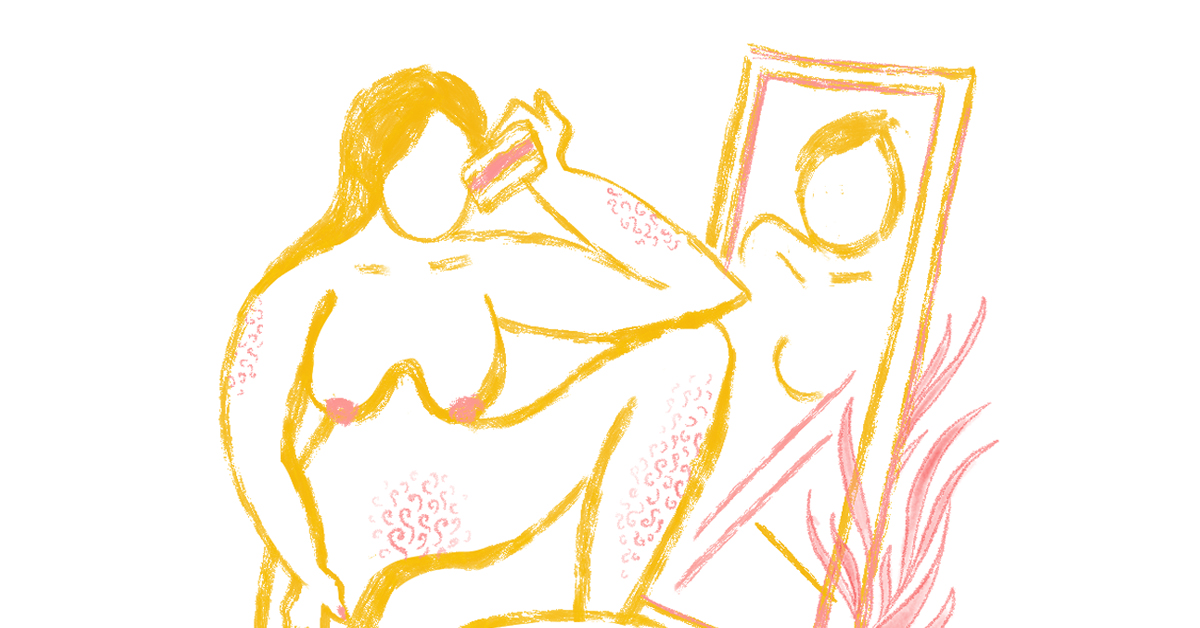

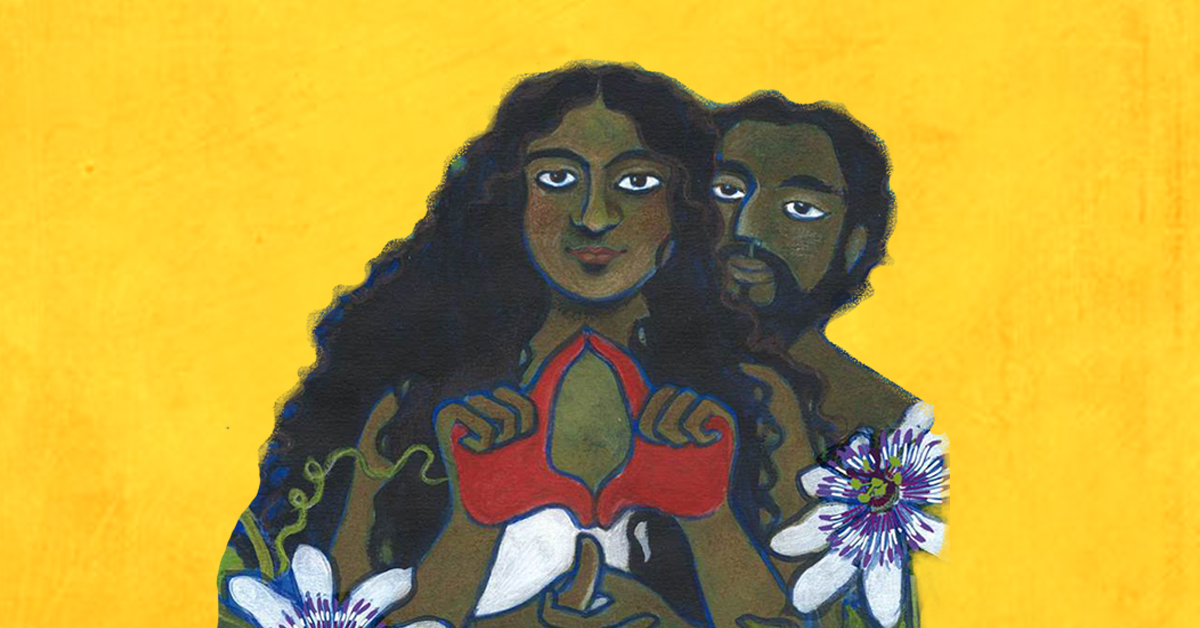

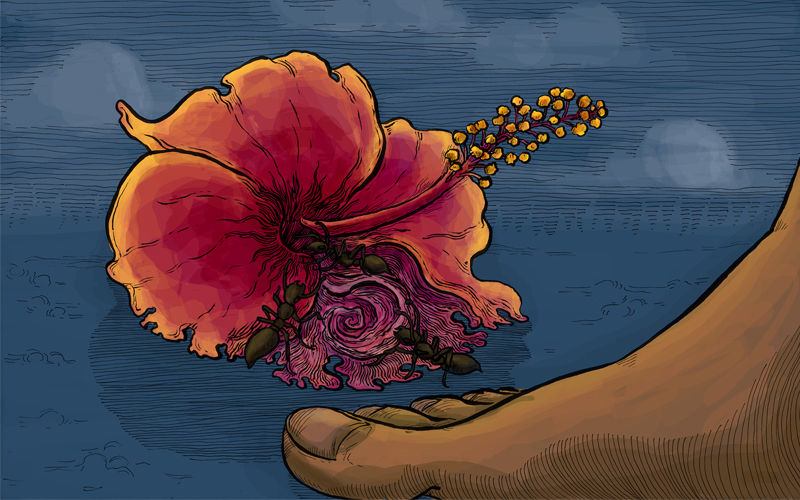

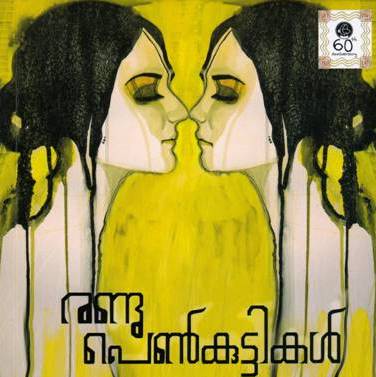

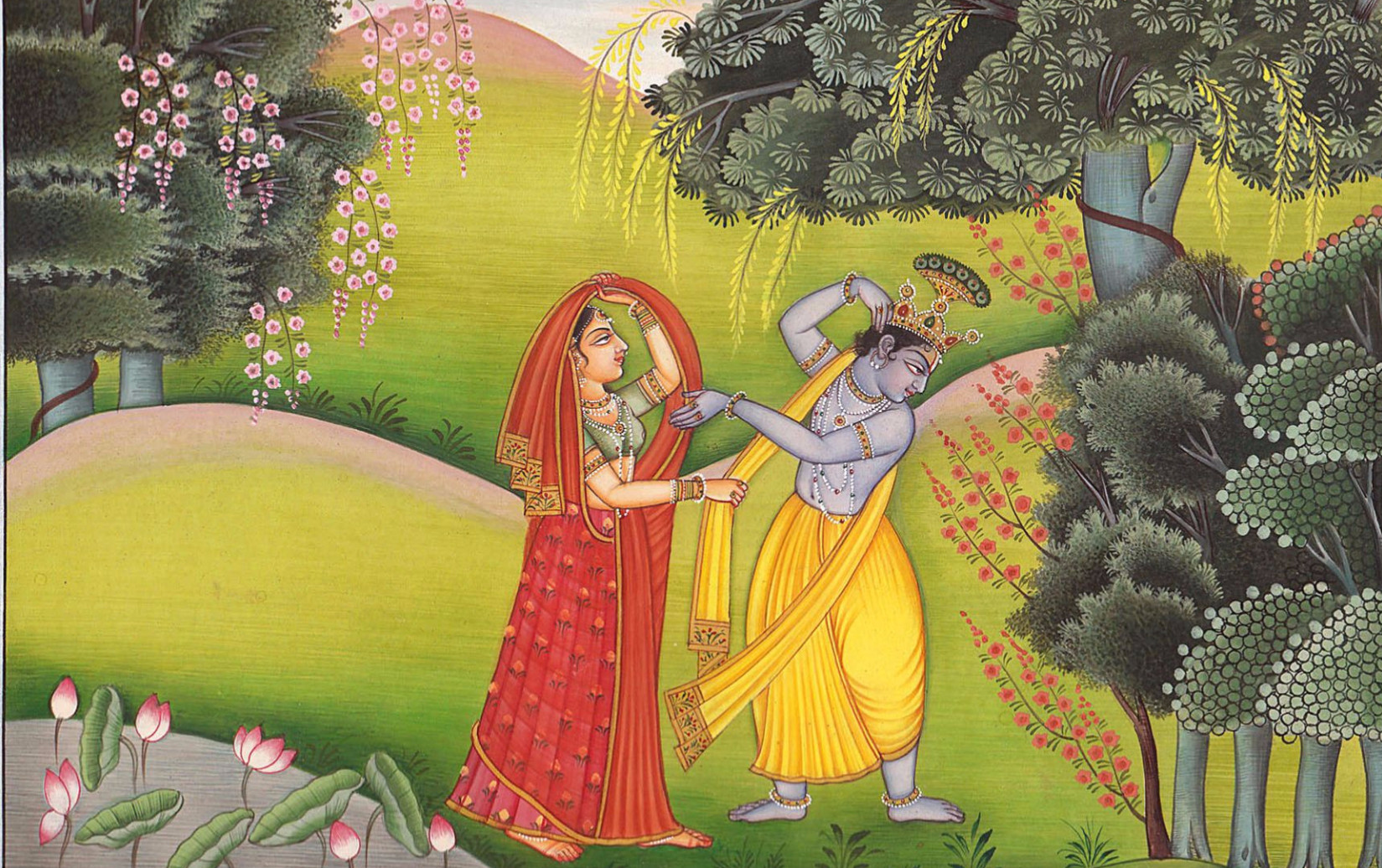

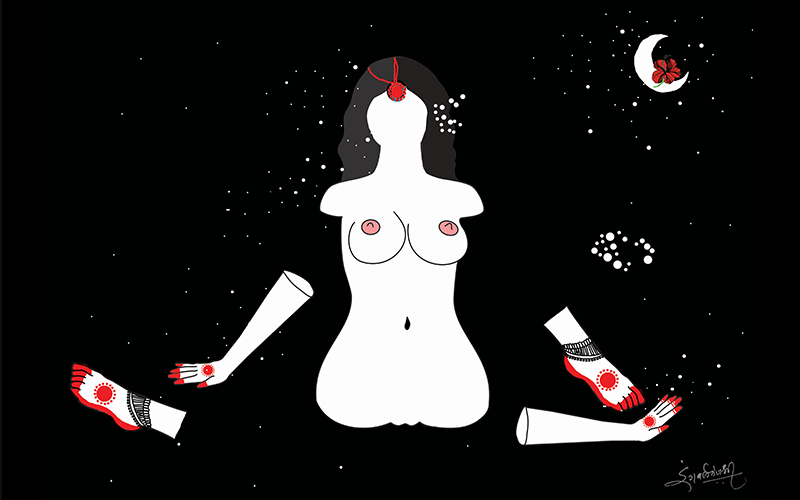

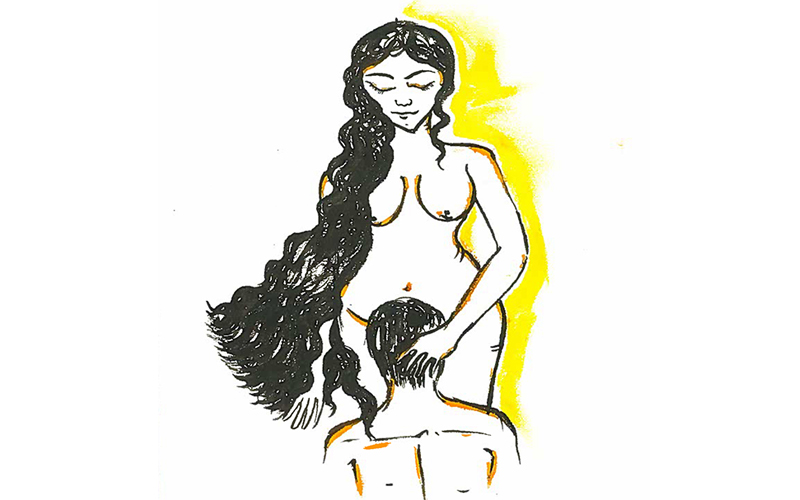

Later, I learned to drape them myself. My lengthy and longing fingers found pleasure in being able to hold all those drapes in one hand by the time I was in grade two. It was my getaway to dance in a saree—emulating my Shakti and Shiva. I always wanted long hair as I felt it echoed the abhinaya of Shakti and tamed the rage of Shiva.

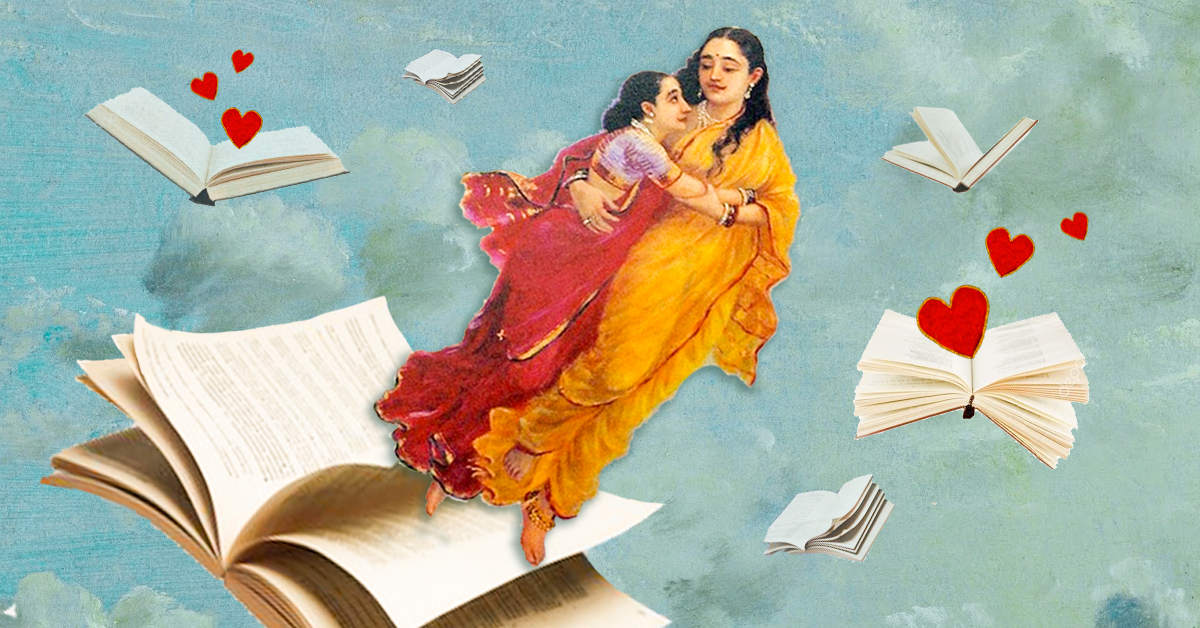

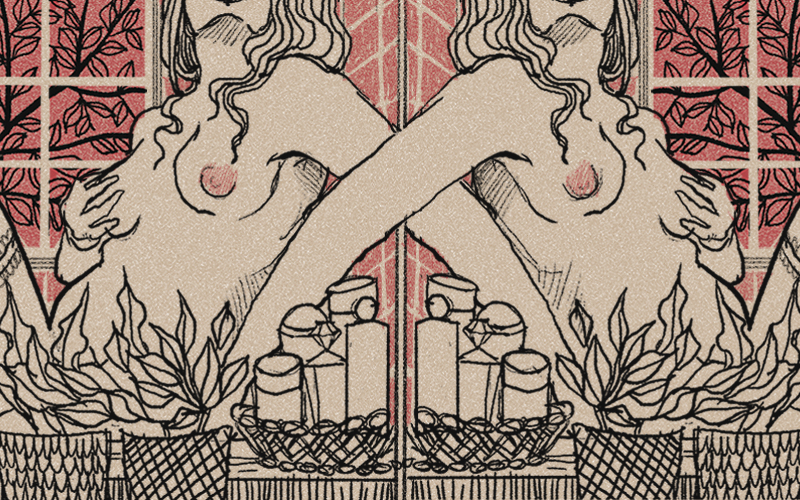

Amma would obsess with silk and gold when there was an event to attend or a family member’s wedding—that had always continued as an enigma about her. Her cotton was more rustic, earthy, and delicate, whereas her silks were dark, deep, and lustrous as they should be. She had her fake and pure silk kaithari saris (traditional Kerala weaves of white and zari borders). She often wore the fake ones to work, whereas the pure ones with silver thread zari border would be starched and ironed in advance before the auspicious occasion she donned them for.

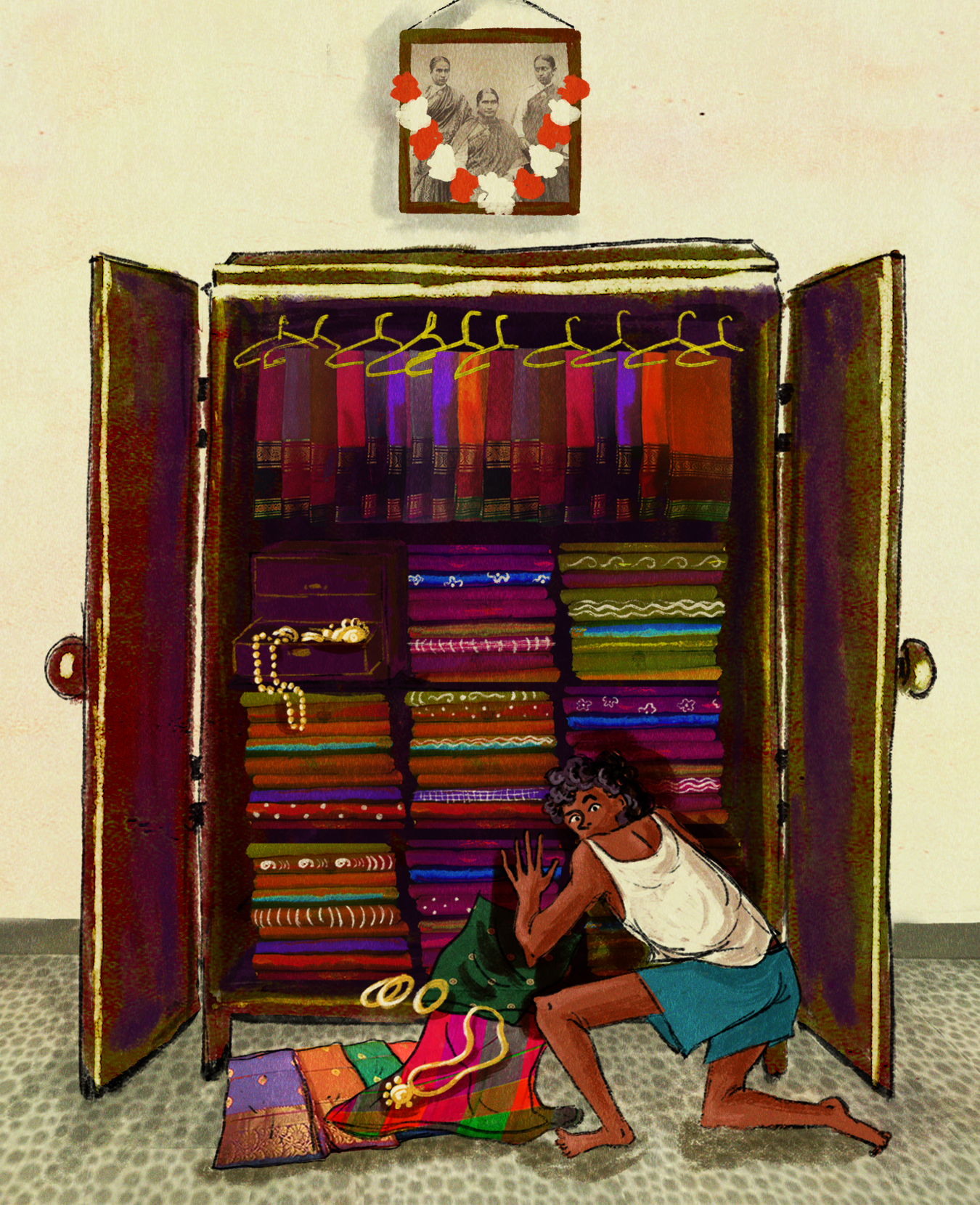

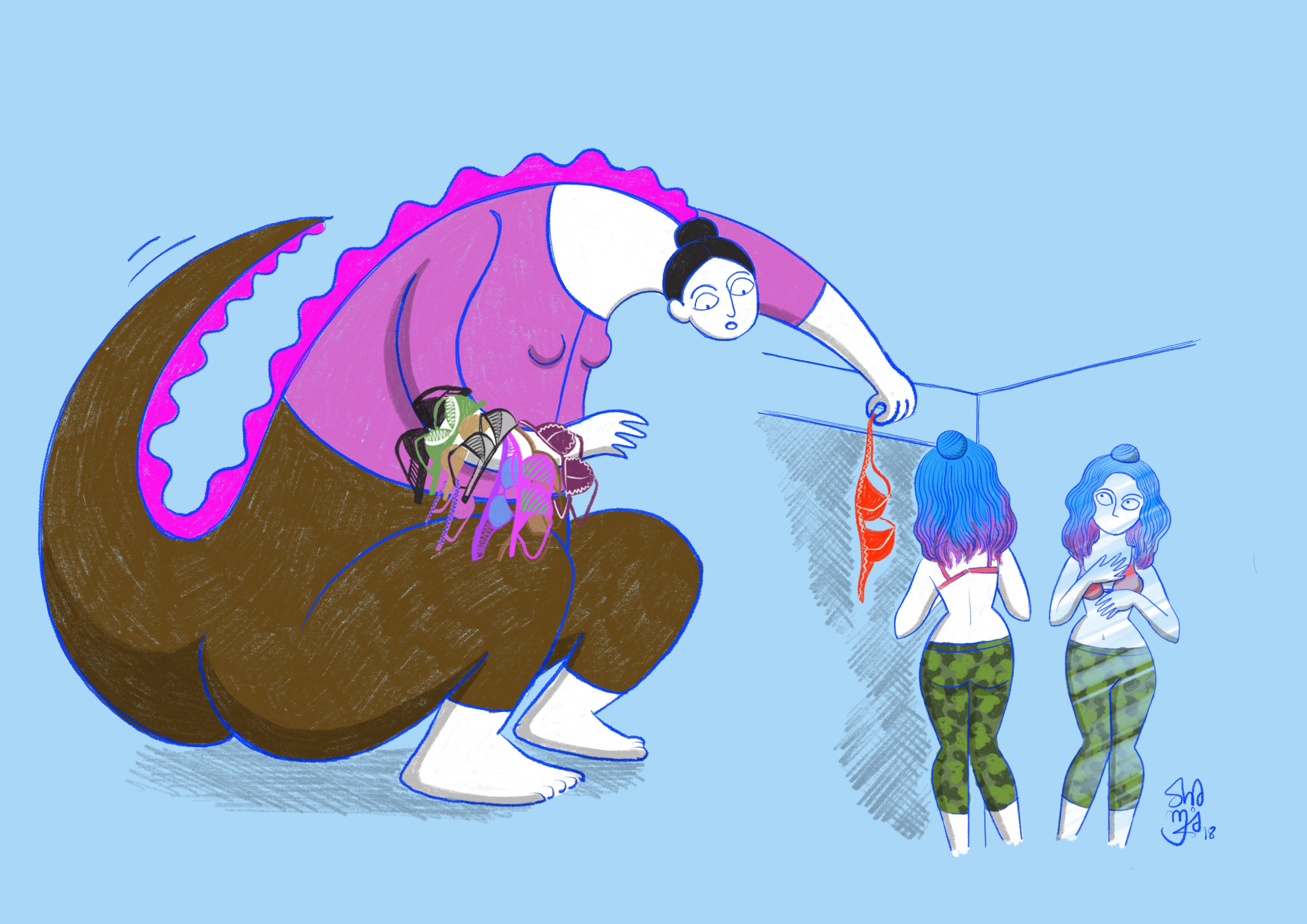

She started dreading my interfering with her dressing cupboard. I was a brat who had eyes on the bright colours of her silk from when I was in kindergarten. She would cleverly hang them on the top row, and my incessant pulling to wear them tore one saree which had ash in body and rustic red on the border. She was able to forgive me then as it was my first time.

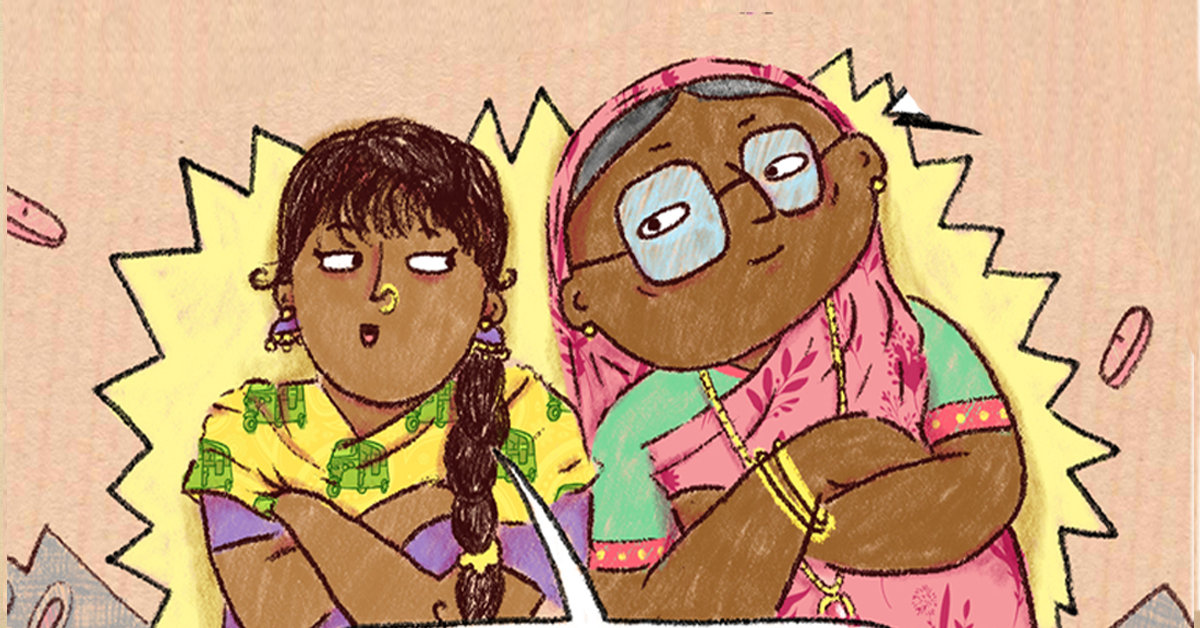

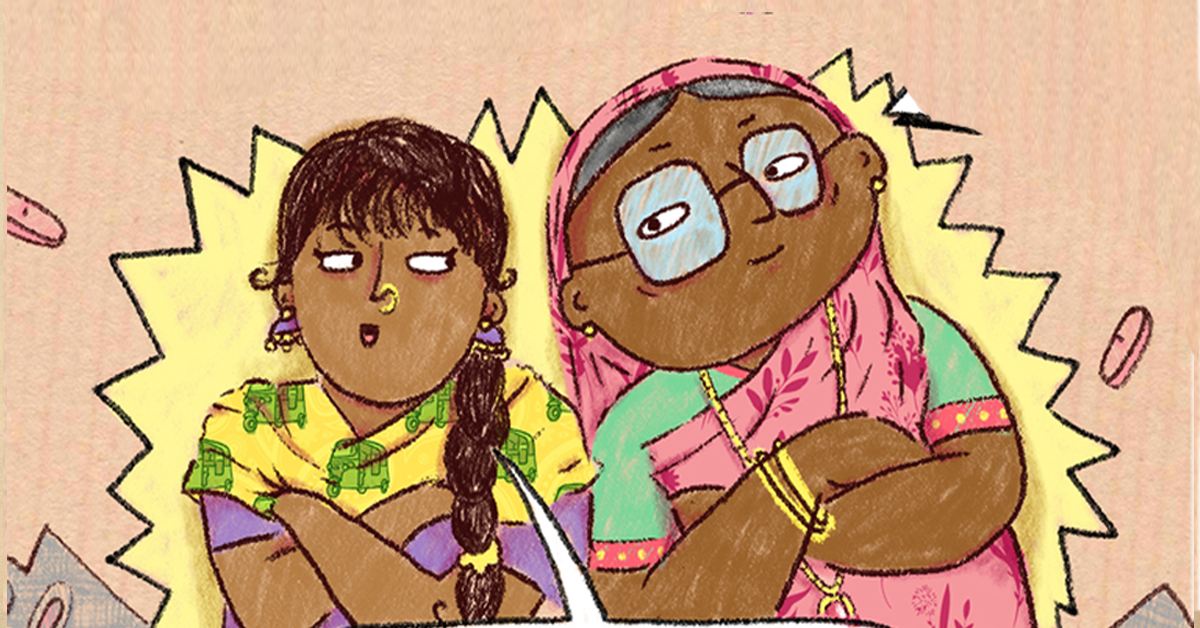

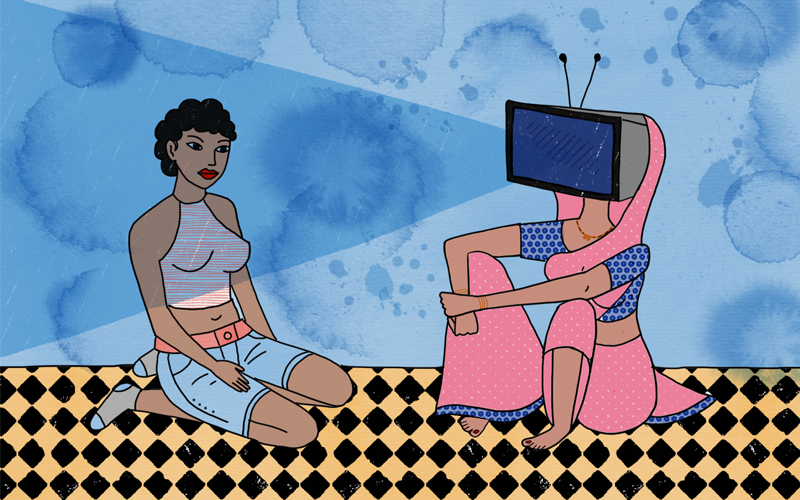

Around the time that we shifted from our happy ground floor apartment to a rented ground floor house, began our catfight or beauty wars (soundharya pinakkam) with each other. Clothes, jewellery and make-up—how my desires for her beauty, becoming mine and us having to share it, was a journey that somehow makes many of us grow up a little too early sometime.

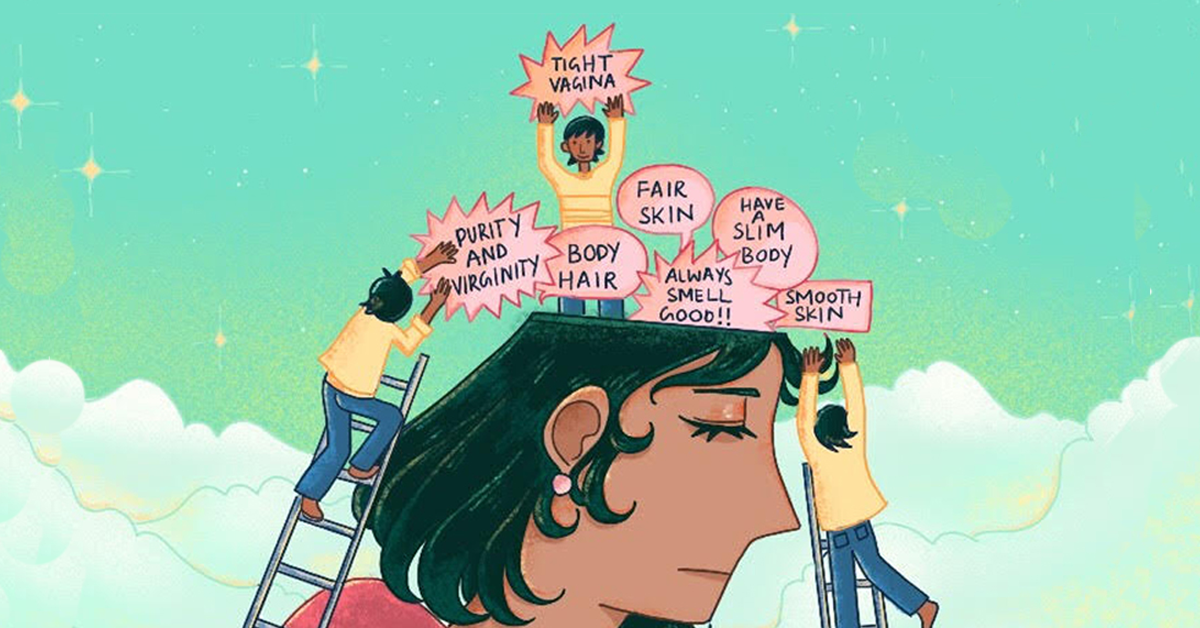

As much as she loved grooming me into a “sundhari” (beautiful girl in Malayalam), I’m not exactly sure of the moment she started resenting or scorning my interests in beauty as per my autonomy. She never allowed me to wear what I liked, even the boy/men’s clothes she always got for me, even in my combinations until I finished college.

When it came to her cupboard of clothes and other belongings—jewellery, beauty products, and other valuables—she would transition into the black and blue devi, commonly known as Badrakali in Kerala. Ready to rip apart everything with the most delirious expressions, phrases, and monosyllables.

She lost it the most when I stole a neighbour girl’s anklet. It was a silver-coloured anklet that was abandoned in their house. I was not the wise thief then and left it hanging on a doorknob in the room I shared with my brother, who found out when I took a break to go and pee.

As soon as I came out of the loo, he held the anklet in his hand and asked me whose it was. I said a classmate had given it to me and snatched it away from him. Later, I threw it away in a nearby plot overgrown with ferns and grass of all kinds.

When Amma got home, my brother told her. She confronted me.

We searched the plot, which ended up with her developing rashes on her feet. The skin around her toes has always been sensitive as her feet were once stamped upon. Anything happening to her toes or feet triggered her and she would break down or lash out.

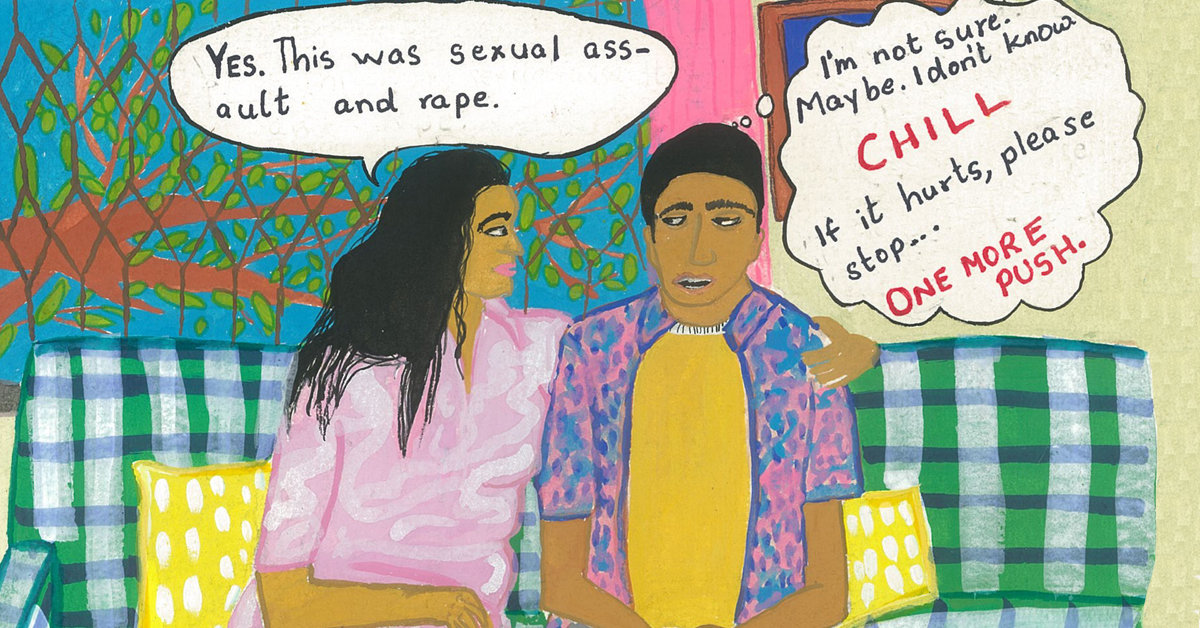

She kicked, hit, screamed, like usual. She bit and did a pirouette with only a part of me that I could only feel or not, with vision and sight dovetailed. She then pushed me to the diwan. She didn't care if I died in that push of hers.

She said, “Might as well die, if you are going to live a life of lies!”

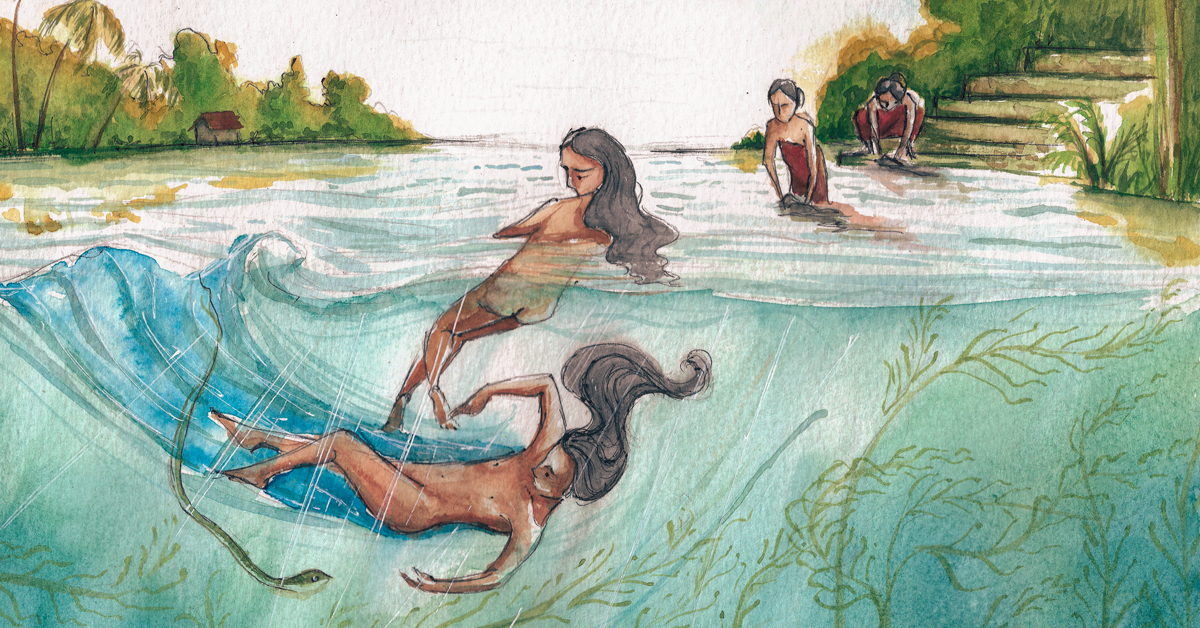

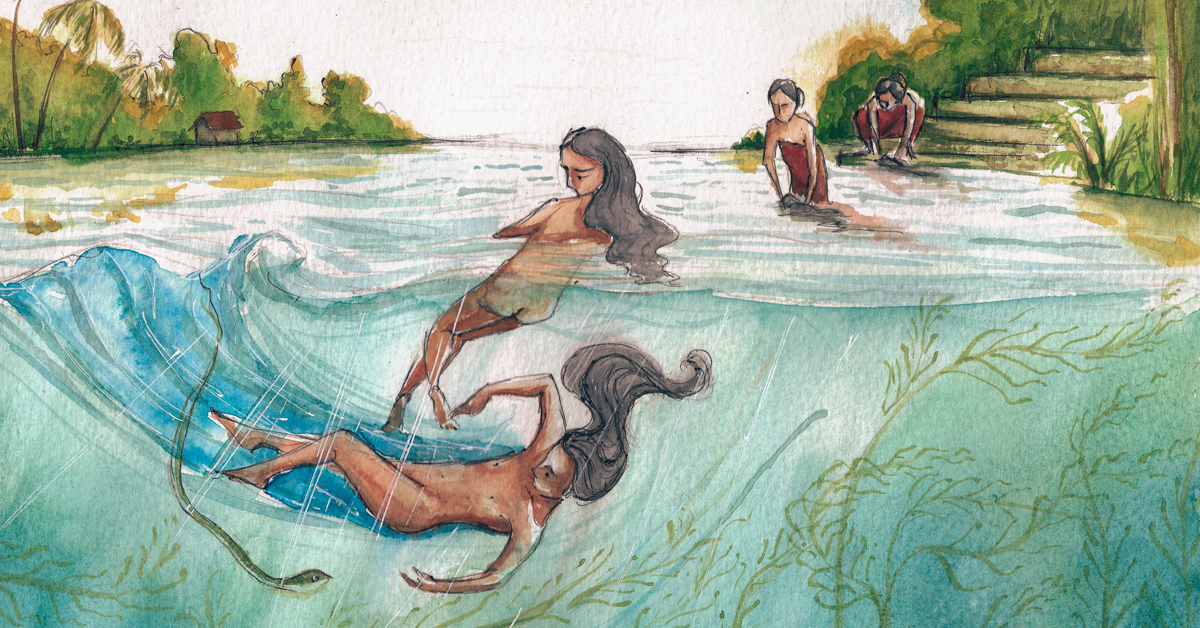

My ways of styling or mixing things while trying new ideas on my own in her room after arriving from school were priceless times of sheer joy. When the ghosts of the house were clear, my baby soul danced and pranced the scenarios ranging from weddings and global stages to the inauspicious undergoing of a Tamil wife’s funeral. Being drenched in countless pots of water was exciting for my soul as I enjoyed being part of the viscosity of water. The soft and clear water capable of cutting stones has always been my favourite amongst the elements. Also, it could be the same flow that inspired the gliding movements of dancers and creators that I too aspired and continues to achieve. Though, I never dared to touch any of her whites as I was sure of death if her whites even moved from the places she left them.

After the anklet incident, these dressed up joys became a shady affair that would happen only in the absence of others. The embarrassment of being caught while not anticipating these people, led me to kill that little performer in me who wanted to dance in my Amma’s saree.

I matched sarees with the shirts of my dad and the basketball jerseys of my brother. Maybe I turned out to be a weirdly wired mix of everyone’s flaws over their strengths. Therefore, it is still a fear to get attached to people as the anxiety of mirroring their flaws over their strengths have been one of my consistent patterns. Hence, my friends are my lovers, to quote writer and performer Alok Vaid Menon.

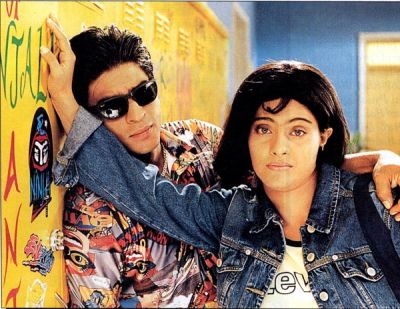

I enacted different scenarios ranging from being a bride to an actress. Sridevi in Devaraagam and Chaalbaaz, Madhuri in Anjaam and Devdas, Remya Krishnan in Padayappa and Panchathanthiram, and Bhanupriya in Azhakiya Raavanan, Azhakan, and Rajashilpi, to name a few.

Amma encouraged and enjoyed my saree-draping playfulness from kindergarten until I turned six or seven. Afterwards, it became a spectacle for my brother to bully me, and this part of wearing sarees and enjoying myself became a dream of the past as soon as I entered my adolescence, though the energy to dance was a fire that somehow always smouldered in me and never really went away and kept me alive along with music always.

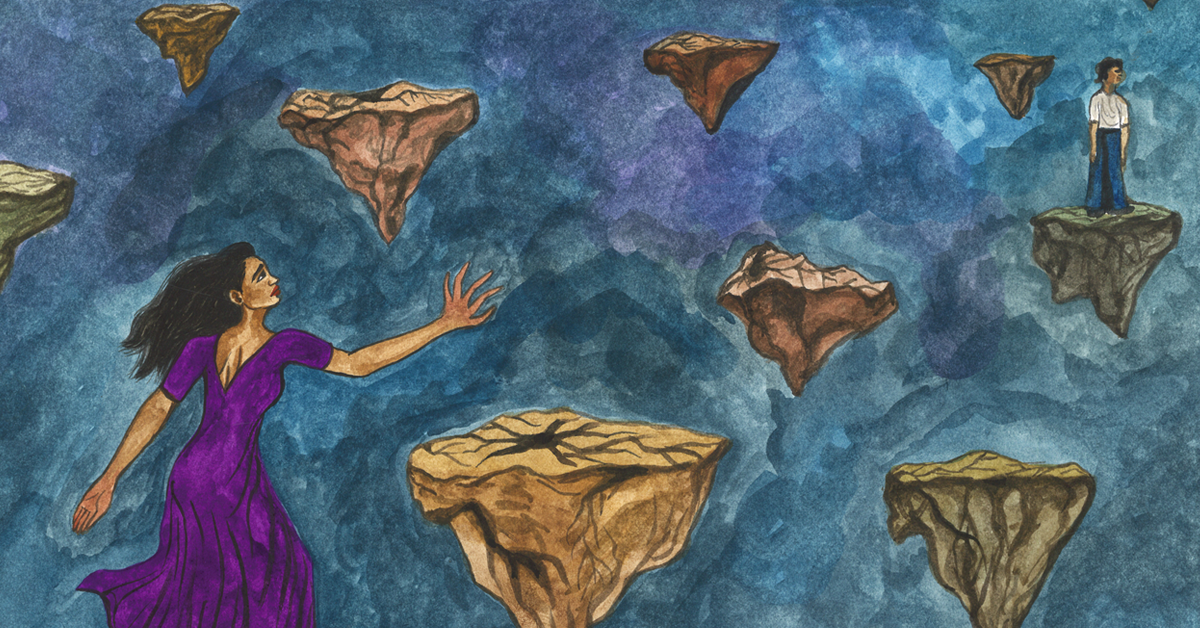

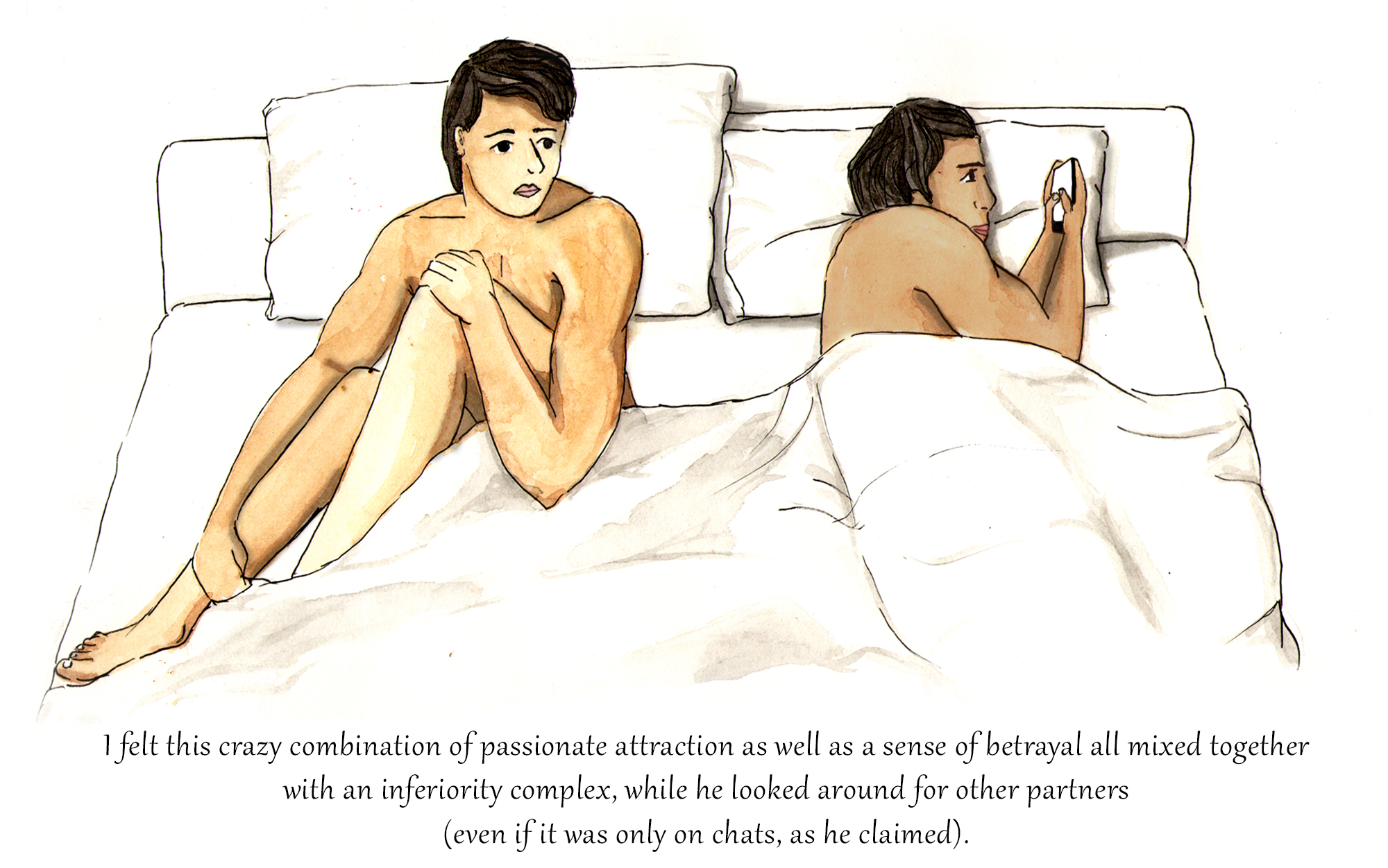

Much of my identity crisis or battles of understanding myself, my tastes, and my needs were hindered and deluded with the intent of wanting to hide this desire of celebrating my femininity by repressing it more than expressing it. This repression leads to major parts of early adulthood turning into a phase of trying to convince everyone “how I’m not like girls.”

To avoid being caught by the bullies and the ghosts of their lingering and evading words, I often avoided confrontations and conflicts. Bullies weren’t just my brother or schoolmates but also parents, who became stricter with me in critique, criticism, discipline, punishments, and eventually the age-old technique of surveying my interests and desires. Everything with good intent in the long run though. As a result of ensuring normalcy and normativity, a part of the self has become blemished. The unhealing of childhood has spilled over into my adult body and I often find that I am mimicking maturity in social and other formal situations without the pure confidence of conviction in owning who I actually am.

It is also a context-specific feeling. Yet, the fact that most of us are either too gay to be straight or too straight to be gay is a conflict of binary that we often face while trying to annihilate binaries or in disagreeing with labels or excessive visibility.

The power, intensity, and fertility of these stages of life were pivotal in shaping my dysregulated and dysfunctional self which still struggles to identify boundaries with people.

As my subtle nuances were punished and rehabilitated. I, too, internalised hate. Adolescence was a time that marked the essential beginning of isolation and solitude but also a point of owning my love for female goddesses and idols in my personal world that enabled and empowered me to escape this drag of performing the manly streak.

Amma’s sarees were a treasure chest waiting to be explored. Each fabric held a story, a texture, and a weight that felt like magic in my little hands. Madras checks with mustard yellow, crimson, brown, and cobalt blue. A sequestered sari in hot pink with silver thread, mirror and sequences in the shapes of tendrils and vines blossoming in different proportions. A Kanchipuram silk sari that she wore for her wedding. I don’t remember seeing her smile in that rustic and ochre golden Mysore silk sari and she seemed rather flustered. Later, when she wore a blue sari for a reception when my father sang an old Yesudas song; are the stories I now remember her telling me joyfully and the same joy reflected in those sepia pictures from the emerging cosmopolitanism of 80s and 90s.

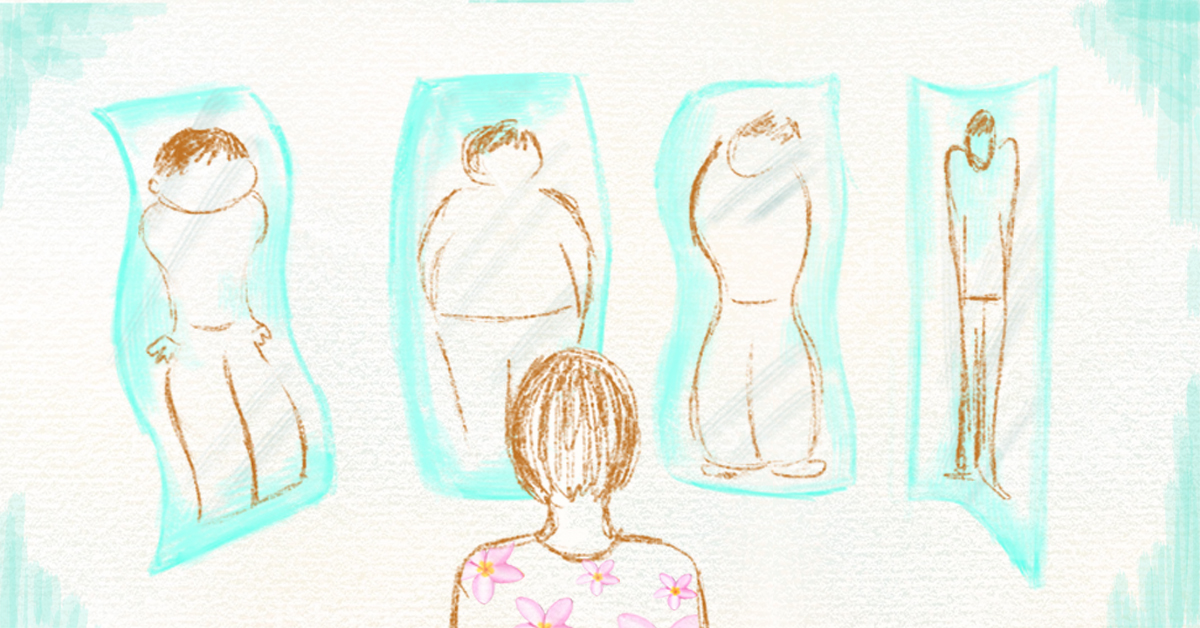

When she draped me in her wedding saree, I immediately felt the weight over it that restricted my antics that always inclined to cinematic dancing and movements. It was a saree I did not feel comfortable moving, performing, or playing around in, and had it removed as soon as I saw myself in it with a blue t-shirt. Amma insisted I tuck in the t-shirt along with the drapes and my shorts being my skirt to hold the saree. I insisted it be outside as always. This fight to tuck things in is a fight we continue to have and how it makes us look more formal and respectable, is still something I am unable to understand, forget practice.

Amma would smile indulgently while dressing me up. Her hands steady as they adjusted the pleats on my tiny frame. For her this was an extension of nurturing. For me it was a portal to a world where I could explore identities far removed from my own.

As I got older, the indulgence waned and now I only buy sarees and look at them or make bed covers out of them. The sarees that were once symbols of joy and dreams, went off-limits. What remained was a cupboard that was as much a fortress as it was a symbol of forbidden desires.

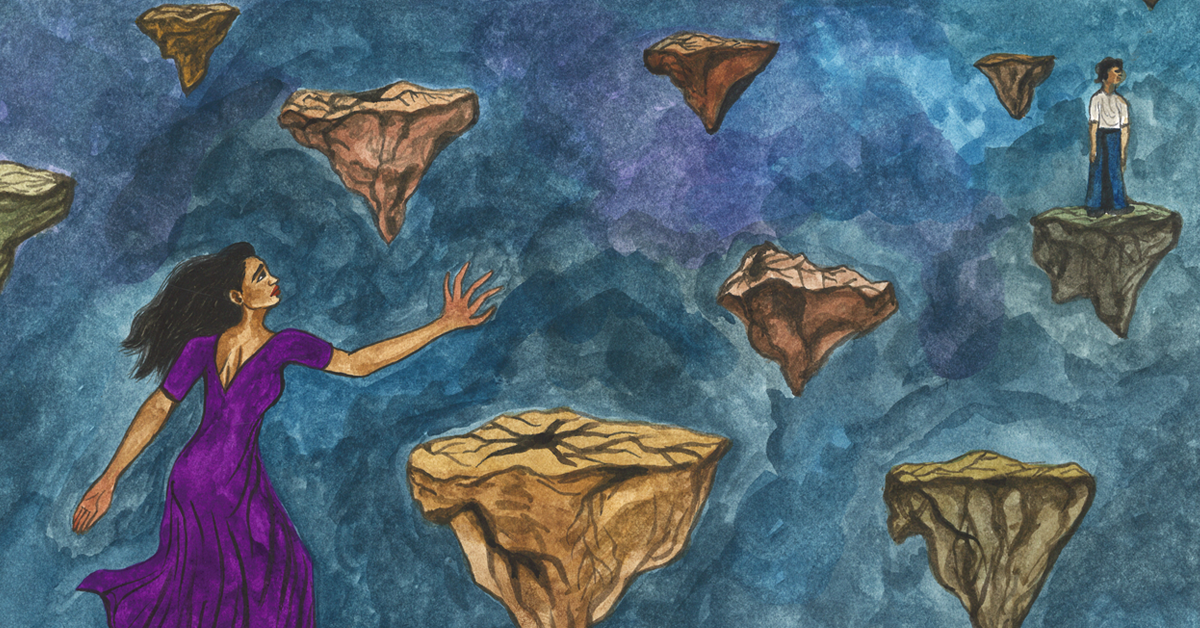

Adolescence brought with it a heightened sense of self-awareness and, unfortunately, the crushing weight of judgment. By this time, my playful experiments with Amma’s sarees had transformed into a secret act of rebellion. These rare moments as they got rarer, were acts of ecstatic thrill—partly because it was forbidden and partly because it allowed me to express a side of myself that I couldn’t show anyone else but myself.

My performances became more elaborate. I wasn’t just a bride or a dancer anymore; I was a movie star, a goddess, a queen. Each saree became a costume, and the mirror became my audience. Yet, this private joy was tinged with guilt and fear.

Amma’s wrath was not to be underestimated. The few times I was caught led to fiery confrontations, clatter of bottles and plates, and days and weeks and months of silences that sounded louder with time.

Her anger wasn’t just about the sarees; it was about control, boundaries, and the roles we were expected to play.

Amma’s sarees were more than garments; they were extensions of her identity. Each piece was chosen with care, reflecting her mood, her aspirations, and her place in the world. The cotton sarees for summer bore simple prints and light colours, while the heavy silks reserved for weddings and celebrations gleamed with gold zari work. To her the sarees represented dignity and decorum. Hence, she never wore even churidars or kurtas to work.

For me, they were freedom, transformation, and magical wings for flying and falling. This dichotomy lay at the heart of our conflicts. My desire to reinterpret the sarees clashed with her need to preserve them as they were—symbols of her hard work, her status, and her legacy.

The cupboard remained a battleground as its shelves holding more than sarees— held the weight of our unspoken expectations and consistently clashing identities. For Amma it was her realm of order with precision. For me it was a portal to becoming someone else.

Her sarees became a metaphor for our relationship—beautiful yet fraught and layered yet delicate.

It wasn’t until I started working in my early twenties that our relationship with the sarees began to shift. Even though I had moved out of parent’s house as a late teenager, I was still carrying the invisible scars of our conflicts. I began to understand Amma’s rigidity not as control but as a form of love wrapped in fear—the fear that I would suffer in a world that has been often unkind to those who deviate and fight and fight for receiving love.

Visiting home one day, I found myself drawn to the cupboard again. This time, it wasn’t to rebel or experiment but to understand. The sarees were the same, yet they looked different to me now. Each fold and pleat felt like a chapter in Amma’s life. I could see the logic in her combinations, the seasonal shifts in her choices, and the care with which she preserved them. Some of them were fraying at the edges and tattering inner parts. Our relationship with the sarees evolved into a shared bond that is often eased with time as the rushing of the process to save time has often led to the abortion of our process and purpose.

The last saree I got her was from Malleshwaram’s Oklipuram in Bangalore. A retailer selling wholesale saris of different types for different seasons and the saree that caught my eye was maroon border with annapakshi motifs placed facing against each other within temple embroidery on a beige-yellow body with tiny white bubbles. They call this design—Madurai Sungudi.

Vibhu is a Former English teacher hoping to become a full-time writer. A multi-talented Mallu juggling different caps and voices to make a film one day.