When the pandemic hit, I was away from home.In the midwestern American college town where I was living, with its long, bleak winters, it would get lonely even otherwise, and bring on pangs of longing for home. At the start of the academic year I had moved in with a flatmate. Life settled into the fairly typical routine of a grad student – classes and research work, teaching duties and domestic chores, all punctuated by a couple of social outings a month.I remember being at a diner and watching the news on television the day in March when a national emergency was finally announced in light of the pandemic. All of a sudden, campus life evaporated into an eerie shadow of itself, as if the academic year had ended. At first, there was a strange kind of thrill in things coming to a standstill. The thrill of evolving-by-the-day developments that impact your life but are also world events, out of proportion with the scale at which most of our lives are lived; of being part of something together, something all too rare as the world gets more stratified. The vestigial thrill, in part, of the child who does not want to go to school and wishes for a miracle, and all of a sudden has their wish granted.Then it began to sink in – what it meant to be indefinitely alone.

At first, there was a strange kind of thrill in things coming to a standstill. The thrill of evolving-by-the-day developments that impact your life but are also world events, out of proportion with the scale at which most of our lives are lived; of being part of something together, something all too rare as the world gets more stratified. The vestigial thrill, in part, of the child who does not want to go to school and wishes for a miracle, and all of a sudden has their wish granted.Then it began to sink in – what it meant to be indefinitely alone. At first, cut off from social interactions, I compulsively consumed news and podcasts, as a way to remain connected with the world, as if this glut of information could help defeat the virus. But underneath, this sense took hold that my body itself was caged and there was nothing I could do about it. It started to feel like my social biome was melting away.The feelings churned and morphed into a period of intense discomfort, even occasional anguish. Deep-seated feelings of anxiety around loneliness bubbled up to the surface and I’d feel physically stifled at times. Especially bad were moments when I wanted to just run out and be among people again, but had to simmer down. My mental health was reeling from the constant pendulum swings, but I didn’t know where to go or what to do to make myself feel better. Nothing seemed to work.The feelings would come in intense waves and leave me exhausted, like someone in withdrawal – but from what exactly? As classes moved online and some semblance of our previous lives began to take on a spectral form, I sought out all manner of mediated socialization. At the end of the day, despite all the virtual communion, this was a need that could only be filled by being physically proximate with other human beings. Nothing, however close, could replace the real thing.

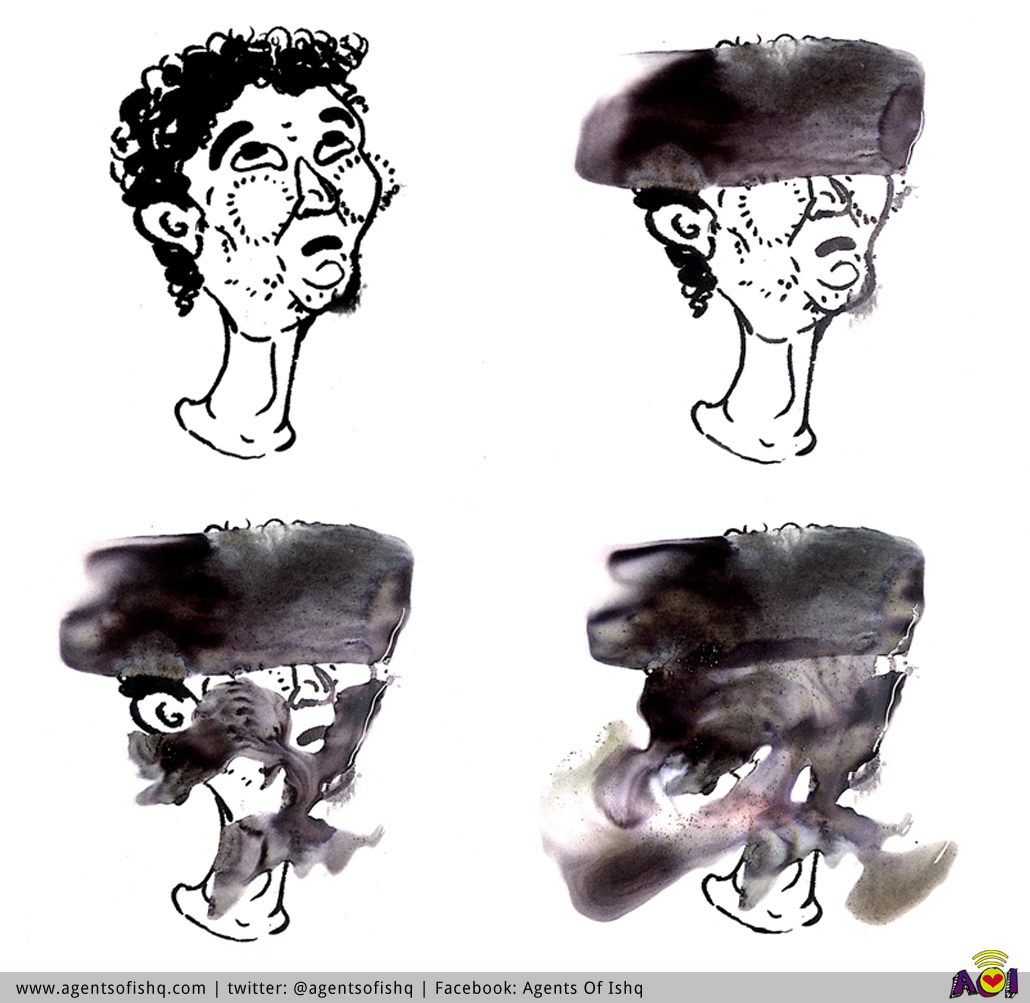

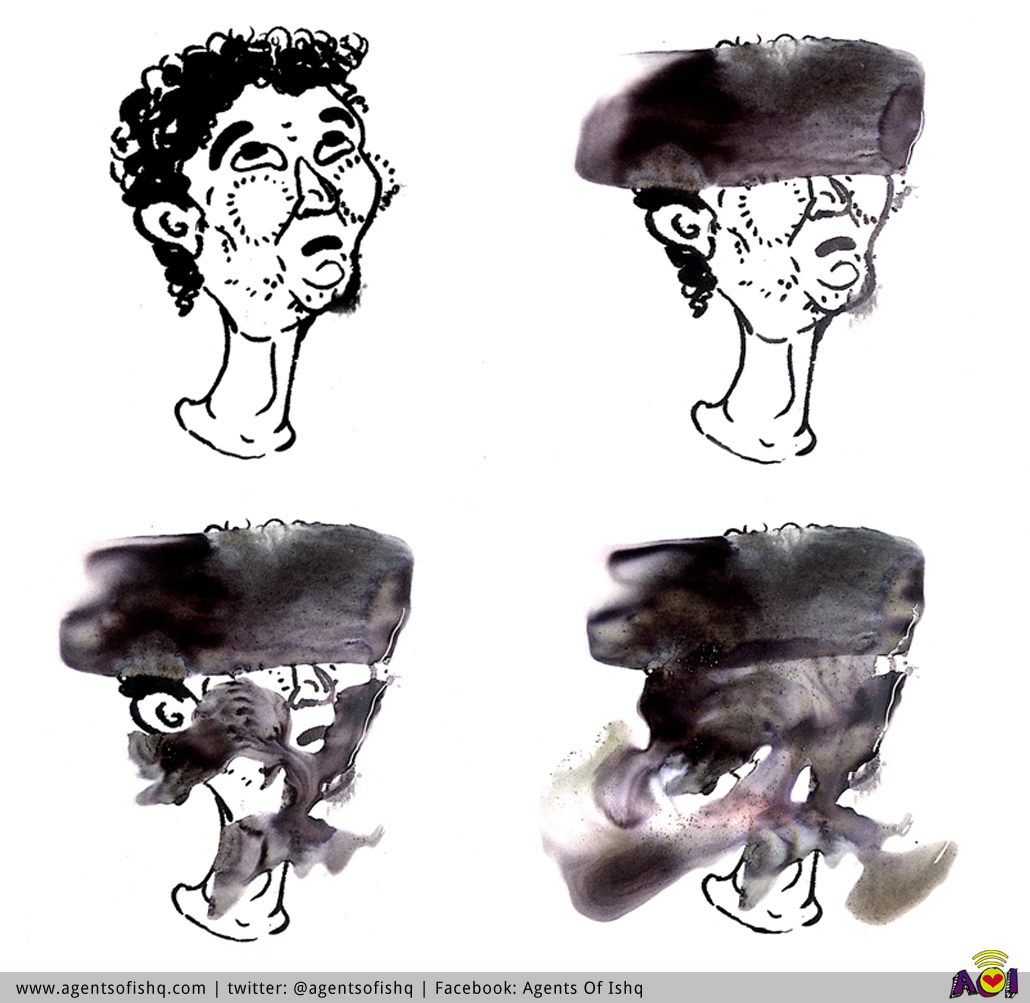

At first, cut off from social interactions, I compulsively consumed news and podcasts, as a way to remain connected with the world, as if this glut of information could help defeat the virus. But underneath, this sense took hold that my body itself was caged and there was nothing I could do about it. It started to feel like my social biome was melting away.The feelings churned and morphed into a period of intense discomfort, even occasional anguish. Deep-seated feelings of anxiety around loneliness bubbled up to the surface and I’d feel physically stifled at times. Especially bad were moments when I wanted to just run out and be among people again, but had to simmer down. My mental health was reeling from the constant pendulum swings, but I didn’t know where to go or what to do to make myself feel better. Nothing seemed to work.The feelings would come in intense waves and leave me exhausted, like someone in withdrawal – but from what exactly? As classes moved online and some semblance of our previous lives began to take on a spectral form, I sought out all manner of mediated socialization. At the end of the day, despite all the virtual communion, this was a need that could only be filled by being physically proximate with other human beings. Nothing, however close, could replace the real thing.  I want to be able to say in the ever-optimistic register of some pithy aphorisms that what doesn't kill you makes you stronger, but that would be glib. Being alone took its toll. But in return it taught me a great deal about myself, even allowed me to stretch the limits of what I thought I could tolerate. For one, it brought into stark relief the shape and texture of the life before, a balance of professional, social and personal time that I felt had worked to give me a sense of well-being, physical, mental and emotional. That was gone, but gone also was the structure that may have allowed me to be unreflective about what might make me teeter on edge, and a dozen other things. I could no longer be distracted from who I was in the absence of all the social roles that I had come to identify with. At one with our most undisguised selves, who are we? I had to start afresh. Here are some things I learned from being alone.First the big stuff. An important result of the isolation, at least in the early days when the peril was fresh and heightened, was that it became a sort of laboratory experiment in personal responsibility. I felt like I was looking down at myself as an isolated subject and my choices were under surveillance.

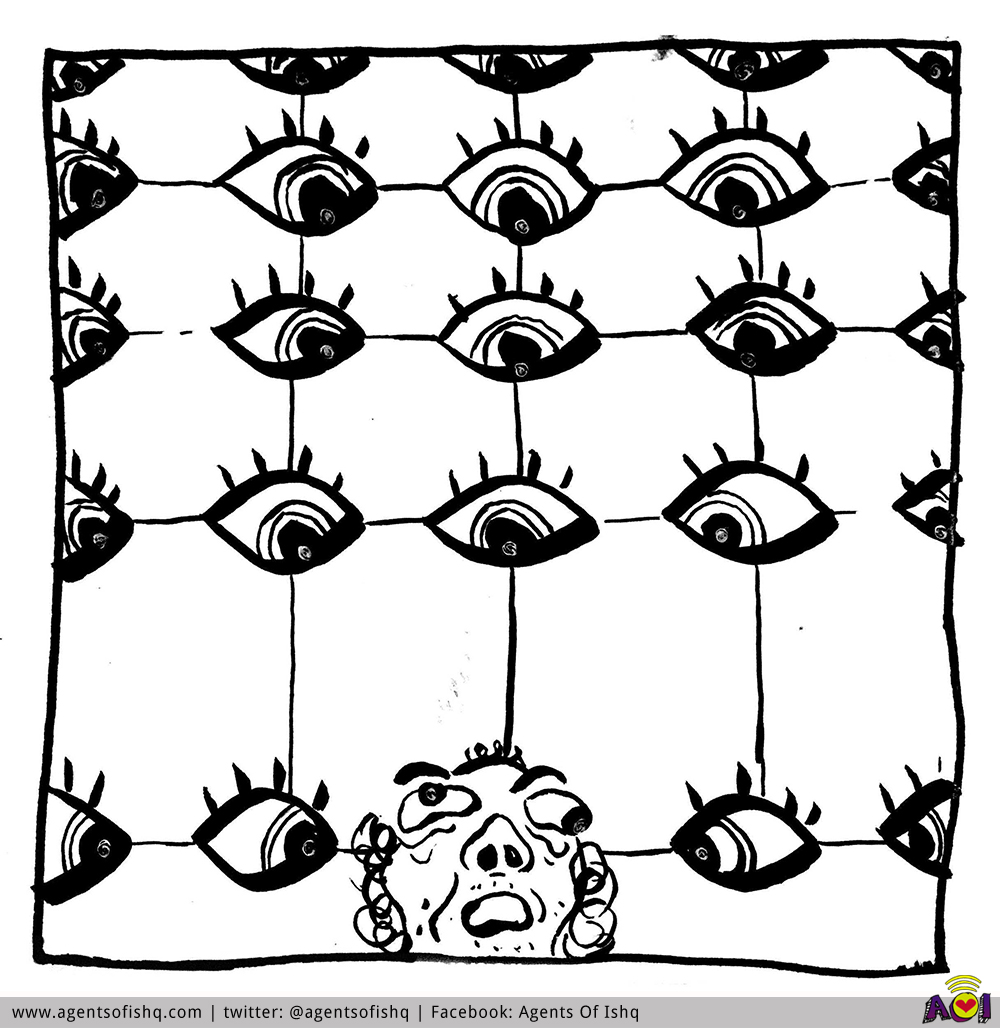

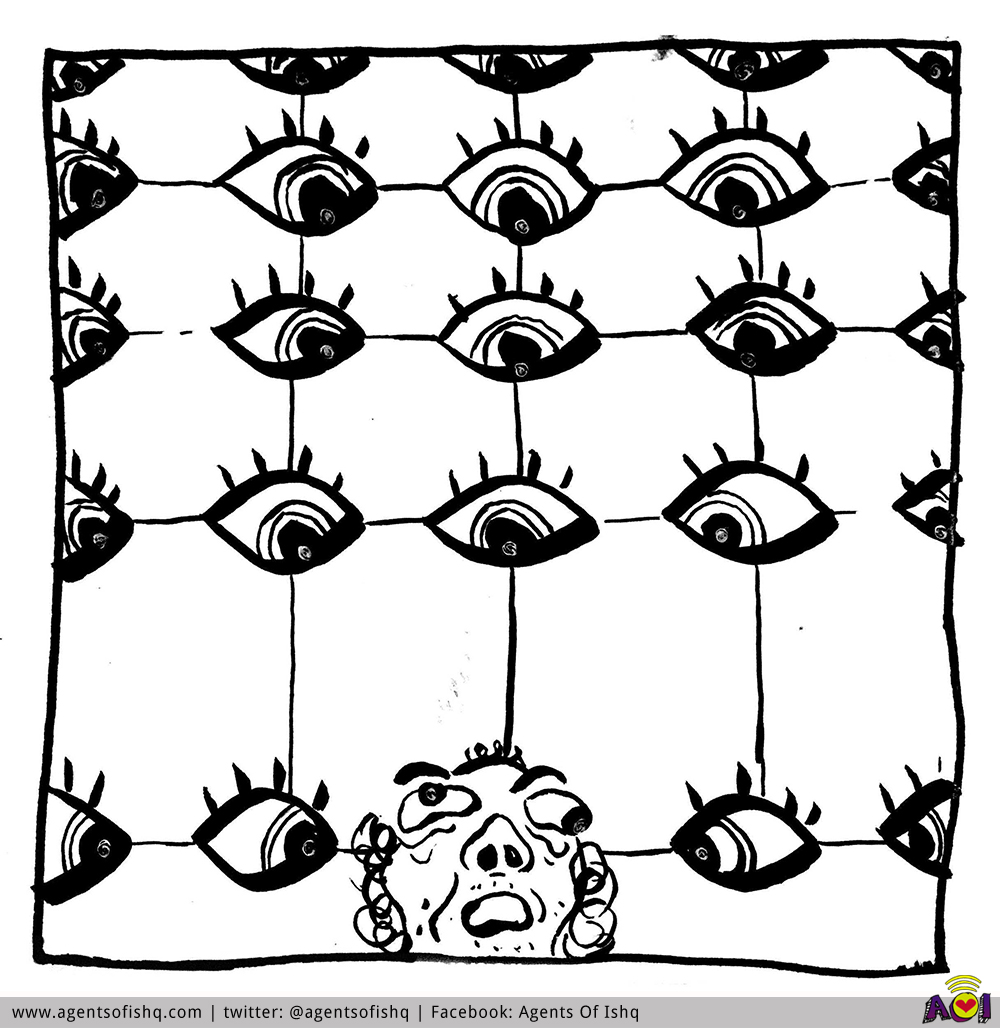

I want to be able to say in the ever-optimistic register of some pithy aphorisms that what doesn't kill you makes you stronger, but that would be glib. Being alone took its toll. But in return it taught me a great deal about myself, even allowed me to stretch the limits of what I thought I could tolerate. For one, it brought into stark relief the shape and texture of the life before, a balance of professional, social and personal time that I felt had worked to give me a sense of well-being, physical, mental and emotional. That was gone, but gone also was the structure that may have allowed me to be unreflective about what might make me teeter on edge, and a dozen other things. I could no longer be distracted from who I was in the absence of all the social roles that I had come to identify with. At one with our most undisguised selves, who are we? I had to start afresh. Here are some things I learned from being alone.First the big stuff. An important result of the isolation, at least in the early days when the peril was fresh and heightened, was that it became a sort of laboratory experiment in personal responsibility. I felt like I was looking down at myself as an isolated subject and my choices were under surveillance. When every action of yours can potentially contribute to the spread of contagion, it acquires a new weight, previously absent. Where secrets and trust and scrutiny and everything gets folded into the shared vulnerability that's dependent on contact, which for those of us who have never had to live through war, insurgency, occupation, or in a police state, was previously unknown. You were no longer responsible only for yourself but also for others known and unknown. Even passing the occasional senior made me think twice about whether my presence might pose a risk. The demands this situation places on us can bring what someone called “moral fatigue” – the idea that when each of your actions has a clear moral consequence for those around you, the stress can wear you out.

When every action of yours can potentially contribute to the spread of contagion, it acquires a new weight, previously absent. Where secrets and trust and scrutiny and everything gets folded into the shared vulnerability that's dependent on contact, which for those of us who have never had to live through war, insurgency, occupation, or in a police state, was previously unknown. You were no longer responsible only for yourself but also for others known and unknown. Even passing the occasional senior made me think twice about whether my presence might pose a risk. The demands this situation places on us can bring what someone called “moral fatigue” – the idea that when each of your actions has a clear moral consequence for those around you, the stress can wear you out. In the sanitized bubble of a thinly-populated American college town, I had the luxury of this introspection. I might have thought less of these risks at home where for hundreds of millions the cost of losing their livelihood is the greater of the two risks. In news from our part of the world, I read of one migrant worker in my hometown who, unable to earn for himself and his family, decided to put an end to it all. He was the same age as I. Regardless of location, it gave me a glimpse of our interdependence in all its fragility and on full display. Even when isolated, we never truly are.But equally important was the little stuff.As someone who is physically affectionate and has a deep need for not-necessarily-sexual physical contact – such as hugging, cuddling or the occasional touch, and no means to meeting these – being alone taught me to learn, painfully, to be comfortable with being alone by myself.When I realized what was missing, it stirred in me a memory from my recent past. One day, when I was leaving after having met someone I knew, they just extended their arms for a hug, like a child would. Of course I hugged them. But as even the simplest of things can seem to someone deprived of them, it struck me as a sort of special ability, one that I lacked. I remember thinking, this is so beautiful, that people are able to do that – reach out and have their needs met. I am convinced that they have been able to do that since they were children, because it came so naturally to them, and that I wasn’t able to because it had never been that way for me growing up. I wondered whether this was something I might be able to change.Being alone taught me about love. And that the love of people – even thousands of miles away – whether family or friends, partners, acquaintances, comrades or colleagues, is all transmitted and can sustain you.

In the sanitized bubble of a thinly-populated American college town, I had the luxury of this introspection. I might have thought less of these risks at home where for hundreds of millions the cost of losing their livelihood is the greater of the two risks. In news from our part of the world, I read of one migrant worker in my hometown who, unable to earn for himself and his family, decided to put an end to it all. He was the same age as I. Regardless of location, it gave me a glimpse of our interdependence in all its fragility and on full display. Even when isolated, we never truly are.But equally important was the little stuff.As someone who is physically affectionate and has a deep need for not-necessarily-sexual physical contact – such as hugging, cuddling or the occasional touch, and no means to meeting these – being alone taught me to learn, painfully, to be comfortable with being alone by myself.When I realized what was missing, it stirred in me a memory from my recent past. One day, when I was leaving after having met someone I knew, they just extended their arms for a hug, like a child would. Of course I hugged them. But as even the simplest of things can seem to someone deprived of them, it struck me as a sort of special ability, one that I lacked. I remember thinking, this is so beautiful, that people are able to do that – reach out and have their needs met. I am convinced that they have been able to do that since they were children, because it came so naturally to them, and that I wasn’t able to because it had never been that way for me growing up. I wondered whether this was something I might be able to change.Being alone taught me about love. And that the love of people – even thousands of miles away – whether family or friends, partners, acquaintances, comrades or colleagues, is all transmitted and can sustain you. I, who rarely called my parents before, began calling them frequently. It became a daily ritual, and one that I looked forward to. Having had my life pared down to the very bones made me value and cherish everyone who was connected to it so much more. I spent more time talking to my flatmate, and sharing the occasional meal or movie night became something far more special and invigorating than before. I had always been in the habit of checking in on friends I had not met for the longest time, but it began to take on a new significance when so many were grappling with mental health issues.I learned that there is love of all shapes and sizes to be shared in all manner of ways. It has taught me of the different ways there are of needing and being there for each other. It taught me to seek companionship with people wherever they are and where they are at in the moment and to the extent they are comfortable with, whether that is physical or virtual. You never want to impose on people, but especially when everyone is struggling with this collective trauma and the ensuing stress, to let people be unless they express or demonstrate a need for you or your company is a learning in emotional humility. Earlier I would sometimes wonder whether I was the only one that struggled with this, but seeing everyone struggling together allowed me to see the conflicts we experience in the light of our shared needs.During this period of intense reflection I was reminded of the words of a practitioner of Zen Buddhism living in town. He recalled his master telling him to be wary of two things: don't collect money [or material things], and don't collect people. Because I keep ticket stubs, plastic covers and receipts and can feel sentimentally attached to the smallest of things not for their material value but for their having been attached to a moment in life, the first is not simple. (I might have a hoarding problem.) But tougher still is the second. How do we not collect people in life? I can understand the wisdom in not wanting to collect a following or entourage and such (listen up, social media users), but the people who come into our lives in whatever way big or small – why is it so much easier for some to let go than it is for others? Let me just say that I would have disappointed the Zen master.As you grow older, life certainly teaches you that you have to let people go. But in the beginning alone-ness also struck me as a somewhat violent thing to do to yourself. Are some people more attuned to and accepting of the metaphor of each person being a satellite, encased in their own little shell and hurtling through space and occasionally passing close by others? Are people with stronger ties to community never really alone, and therefore more readily able to be physically alone? Do some of us need community, in all different senses of the word, more than others who are satisfied in their isolation and don’t experience it as loneliness? Is it really the balance of the shared (community) life and the personal (private) life that most of our pre-Covid lives had reached that keeps things on even keel? My thoughts were inundated with these reflections, and any answers that came forth were untested.

I, who rarely called my parents before, began calling them frequently. It became a daily ritual, and one that I looked forward to. Having had my life pared down to the very bones made me value and cherish everyone who was connected to it so much more. I spent more time talking to my flatmate, and sharing the occasional meal or movie night became something far more special and invigorating than before. I had always been in the habit of checking in on friends I had not met for the longest time, but it began to take on a new significance when so many were grappling with mental health issues.I learned that there is love of all shapes and sizes to be shared in all manner of ways. It has taught me of the different ways there are of needing and being there for each other. It taught me to seek companionship with people wherever they are and where they are at in the moment and to the extent they are comfortable with, whether that is physical or virtual. You never want to impose on people, but especially when everyone is struggling with this collective trauma and the ensuing stress, to let people be unless they express or demonstrate a need for you or your company is a learning in emotional humility. Earlier I would sometimes wonder whether I was the only one that struggled with this, but seeing everyone struggling together allowed me to see the conflicts we experience in the light of our shared needs.During this period of intense reflection I was reminded of the words of a practitioner of Zen Buddhism living in town. He recalled his master telling him to be wary of two things: don't collect money [or material things], and don't collect people. Because I keep ticket stubs, plastic covers and receipts and can feel sentimentally attached to the smallest of things not for their material value but for their having been attached to a moment in life, the first is not simple. (I might have a hoarding problem.) But tougher still is the second. How do we not collect people in life? I can understand the wisdom in not wanting to collect a following or entourage and such (listen up, social media users), but the people who come into our lives in whatever way big or small – why is it so much easier for some to let go than it is for others? Let me just say that I would have disappointed the Zen master.As you grow older, life certainly teaches you that you have to let people go. But in the beginning alone-ness also struck me as a somewhat violent thing to do to yourself. Are some people more attuned to and accepting of the metaphor of each person being a satellite, encased in their own little shell and hurtling through space and occasionally passing close by others? Are people with stronger ties to community never really alone, and therefore more readily able to be physically alone? Do some of us need community, in all different senses of the word, more than others who are satisfied in their isolation and don’t experience it as loneliness? Is it really the balance of the shared (community) life and the personal (private) life that most of our pre-Covid lives had reached that keeps things on even keel? My thoughts were inundated with these reflections, and any answers that came forth were untested.  I also learned something new about work. How certain kinds of work by their very nature (like the work some of us as researchers or writers do) can isolate you, take you deeper within to make you seem almost self-enclosed. But when there is no longer a social scaffolding to support you, the isolation is doubly felt. It might make it more comfortable for you to be on your own because the work itself, we like to believe, is worth something and its value enduring. On the flipside, does it also give you a deluded, inflated sense of your own worth? After a long period in which I was unable to bring myself to work, I grappled both with the sacrifices that this life calls for and the privilege of doing the sort of work that you could carry on with in these times. I saw around me people whom the isolation didn’t affect much in any obvious way. I know many who were perfectly happy being alone before and some have even come to enjoy having to see less of people. We have also discovered ways of doing without what was superfluous to us both as individuals and as an aggregate, granting that a lot of this comes with privilege. Are we all wired differently, or does the situation force us to adapt?Speaking for myself, I continue to find enforced isolation something I cannot do to myself in good conscience. But looking back now, I see that maybe, like a person going through withdrawal, I was also building endurance all along for something else: to be alone for longer periods. Is this what we call resilience?If one must reflect and grow, then this is as good or bad a circumstance to do that as any. It may or may not leave you changed, but there is a lot to learn. And it is not over yet.It’s been over five months since the weekend in March when the pandemic was declared, and a month since I returned home to all its warmth and the physical company of people I love. I value them more. I value our time spent together a lot more because I have yearned for it for half a year. I value personal sacrifices for collective well-being and solidarity in the face of danger. I value us all. The first time I went out to be among a crowd of people was for a Black Lives Matter protest. Despite the initial trepidation, it was heartening to see people wearing cloth masks out in numbers, with volunteers carrying sanitizers bobbing in and out amongst us. Even as we dealt with this new scourge, people had been facing epidemics less pathogenic, but as pathological, and battling those could not wait. At the end of the protest, a group of young people took to the streets dancing and their joy was infectious. There were things that were important enough for us to start easing the norms of social isolation. Navdeep has made one documentary, and finds that he enjoys research in media and film history more, for now. He just completed a master’s thesis on international non-theatrical sponsored film programs in post-independence India and is working on converting it into a form that fits people’s attention spans. He is a founding member of the Bi Collective Delhi. Sukh Mehak Kaur (BFA, MVA) is a comix artist and illustrator based in Ropar, Punjab. She is currently pursuing her goals to become a children's illustrator.

I also learned something new about work. How certain kinds of work by their very nature (like the work some of us as researchers or writers do) can isolate you, take you deeper within to make you seem almost self-enclosed. But when there is no longer a social scaffolding to support you, the isolation is doubly felt. It might make it more comfortable for you to be on your own because the work itself, we like to believe, is worth something and its value enduring. On the flipside, does it also give you a deluded, inflated sense of your own worth? After a long period in which I was unable to bring myself to work, I grappled both with the sacrifices that this life calls for and the privilege of doing the sort of work that you could carry on with in these times. I saw around me people whom the isolation didn’t affect much in any obvious way. I know many who were perfectly happy being alone before and some have even come to enjoy having to see less of people. We have also discovered ways of doing without what was superfluous to us both as individuals and as an aggregate, granting that a lot of this comes with privilege. Are we all wired differently, or does the situation force us to adapt?Speaking for myself, I continue to find enforced isolation something I cannot do to myself in good conscience. But looking back now, I see that maybe, like a person going through withdrawal, I was also building endurance all along for something else: to be alone for longer periods. Is this what we call resilience?If one must reflect and grow, then this is as good or bad a circumstance to do that as any. It may or may not leave you changed, but there is a lot to learn. And it is not over yet.It’s been over five months since the weekend in March when the pandemic was declared, and a month since I returned home to all its warmth and the physical company of people I love. I value them more. I value our time spent together a lot more because I have yearned for it for half a year. I value personal sacrifices for collective well-being and solidarity in the face of danger. I value us all. The first time I went out to be among a crowd of people was for a Black Lives Matter protest. Despite the initial trepidation, it was heartening to see people wearing cloth masks out in numbers, with volunteers carrying sanitizers bobbing in and out amongst us. Even as we dealt with this new scourge, people had been facing epidemics less pathogenic, but as pathological, and battling those could not wait. At the end of the protest, a group of young people took to the streets dancing and their joy was infectious. There were things that were important enough for us to start easing the norms of social isolation. Navdeep has made one documentary, and finds that he enjoys research in media and film history more, for now. He just completed a master’s thesis on international non-theatrical sponsored film programs in post-independence India and is working on converting it into a form that fits people’s attention spans. He is a founding member of the Bi Collective Delhi. Sukh Mehak Kaur (BFA, MVA) is a comix artist and illustrator based in Ropar, Punjab. She is currently pursuing her goals to become a children's illustrator.

At first, there was a strange kind of thrill in things coming to a standstill. The thrill of evolving-by-the-day developments that impact your life but are also world events, out of proportion with the scale at which most of our lives are lived; of being part of something together, something all too rare as the world gets more stratified. The vestigial thrill, in part, of the child who does not want to go to school and wishes for a miracle, and all of a sudden has their wish granted.Then it began to sink in – what it meant to be indefinitely alone.

At first, there was a strange kind of thrill in things coming to a standstill. The thrill of evolving-by-the-day developments that impact your life but are also world events, out of proportion with the scale at which most of our lives are lived; of being part of something together, something all too rare as the world gets more stratified. The vestigial thrill, in part, of the child who does not want to go to school and wishes for a miracle, and all of a sudden has their wish granted.Then it began to sink in – what it meant to be indefinitely alone. At first, cut off from social interactions, I compulsively consumed news and podcasts, as a way to remain connected with the world, as if this glut of information could help defeat the virus. But underneath, this sense took hold that my body itself was caged and there was nothing I could do about it. It started to feel like my social biome was melting away.The feelings churned and morphed into a period of intense discomfort, even occasional anguish. Deep-seated feelings of anxiety around loneliness bubbled up to the surface and I’d feel physically stifled at times. Especially bad were moments when I wanted to just run out and be among people again, but had to simmer down. My mental health was reeling from the constant pendulum swings, but I didn’t know where to go or what to do to make myself feel better. Nothing seemed to work.The feelings would come in intense waves and leave me exhausted, like someone in withdrawal – but from what exactly? As classes moved online and some semblance of our previous lives began to take on a spectral form, I sought out all manner of mediated socialization. At the end of the day, despite all the virtual communion, this was a need that could only be filled by being physically proximate with other human beings. Nothing, however close, could replace the real thing.

At first, cut off from social interactions, I compulsively consumed news and podcasts, as a way to remain connected with the world, as if this glut of information could help defeat the virus. But underneath, this sense took hold that my body itself was caged and there was nothing I could do about it. It started to feel like my social biome was melting away.The feelings churned and morphed into a period of intense discomfort, even occasional anguish. Deep-seated feelings of anxiety around loneliness bubbled up to the surface and I’d feel physically stifled at times. Especially bad were moments when I wanted to just run out and be among people again, but had to simmer down. My mental health was reeling from the constant pendulum swings, but I didn’t know where to go or what to do to make myself feel better. Nothing seemed to work.The feelings would come in intense waves and leave me exhausted, like someone in withdrawal – but from what exactly? As classes moved online and some semblance of our previous lives began to take on a spectral form, I sought out all manner of mediated socialization. At the end of the day, despite all the virtual communion, this was a need that could only be filled by being physically proximate with other human beings. Nothing, however close, could replace the real thing.  I want to be able to say in the ever-optimistic register of some pithy aphorisms that what doesn't kill you makes you stronger, but that would be glib. Being alone took its toll. But in return it taught me a great deal about myself, even allowed me to stretch the limits of what I thought I could tolerate. For one, it brought into stark relief the shape and texture of the life before, a balance of professional, social and personal time that I felt had worked to give me a sense of well-being, physical, mental and emotional. That was gone, but gone also was the structure that may have allowed me to be unreflective about what might make me teeter on edge, and a dozen other things. I could no longer be distracted from who I was in the absence of all the social roles that I had come to identify with. At one with our most undisguised selves, who are we? I had to start afresh. Here are some things I learned from being alone.First the big stuff. An important result of the isolation, at least in the early days when the peril was fresh and heightened, was that it became a sort of laboratory experiment in personal responsibility. I felt like I was looking down at myself as an isolated subject and my choices were under surveillance.

I want to be able to say in the ever-optimistic register of some pithy aphorisms that what doesn't kill you makes you stronger, but that would be glib. Being alone took its toll. But in return it taught me a great deal about myself, even allowed me to stretch the limits of what I thought I could tolerate. For one, it brought into stark relief the shape and texture of the life before, a balance of professional, social and personal time that I felt had worked to give me a sense of well-being, physical, mental and emotional. That was gone, but gone also was the structure that may have allowed me to be unreflective about what might make me teeter on edge, and a dozen other things. I could no longer be distracted from who I was in the absence of all the social roles that I had come to identify with. At one with our most undisguised selves, who are we? I had to start afresh. Here are some things I learned from being alone.First the big stuff. An important result of the isolation, at least in the early days when the peril was fresh and heightened, was that it became a sort of laboratory experiment in personal responsibility. I felt like I was looking down at myself as an isolated subject and my choices were under surveillance. When every action of yours can potentially contribute to the spread of contagion, it acquires a new weight, previously absent. Where secrets and trust and scrutiny and everything gets folded into the shared vulnerability that's dependent on contact, which for those of us who have never had to live through war, insurgency, occupation, or in a police state, was previously unknown. You were no longer responsible only for yourself but also for others known and unknown. Even passing the occasional senior made me think twice about whether my presence might pose a risk. The demands this situation places on us can bring what someone called “moral fatigue” – the idea that when each of your actions has a clear moral consequence for those around you, the stress can wear you out.

When every action of yours can potentially contribute to the spread of contagion, it acquires a new weight, previously absent. Where secrets and trust and scrutiny and everything gets folded into the shared vulnerability that's dependent on contact, which for those of us who have never had to live through war, insurgency, occupation, or in a police state, was previously unknown. You were no longer responsible only for yourself but also for others known and unknown. Even passing the occasional senior made me think twice about whether my presence might pose a risk. The demands this situation places on us can bring what someone called “moral fatigue” – the idea that when each of your actions has a clear moral consequence for those around you, the stress can wear you out. In the sanitized bubble of a thinly-populated American college town, I had the luxury of this introspection. I might have thought less of these risks at home where for hundreds of millions the cost of losing their livelihood is the greater of the two risks. In news from our part of the world, I read of one migrant worker in my hometown who, unable to earn for himself and his family, decided to put an end to it all. He was the same age as I. Regardless of location, it gave me a glimpse of our interdependence in all its fragility and on full display. Even when isolated, we never truly are.But equally important was the little stuff.As someone who is physically affectionate and has a deep need for not-necessarily-sexual physical contact – such as hugging, cuddling or the occasional touch, and no means to meeting these – being alone taught me to learn, painfully, to be comfortable with being alone by myself.When I realized what was missing, it stirred in me a memory from my recent past. One day, when I was leaving after having met someone I knew, they just extended their arms for a hug, like a child would. Of course I hugged them. But as even the simplest of things can seem to someone deprived of them, it struck me as a sort of special ability, one that I lacked. I remember thinking, this is so beautiful, that people are able to do that – reach out and have their needs met. I am convinced that they have been able to do that since they were children, because it came so naturally to them, and that I wasn’t able to because it had never been that way for me growing up. I wondered whether this was something I might be able to change.Being alone taught me about love. And that the love of people – even thousands of miles away – whether family or friends, partners, acquaintances, comrades or colleagues, is all transmitted and can sustain you.

In the sanitized bubble of a thinly-populated American college town, I had the luxury of this introspection. I might have thought less of these risks at home where for hundreds of millions the cost of losing their livelihood is the greater of the two risks. In news from our part of the world, I read of one migrant worker in my hometown who, unable to earn for himself and his family, decided to put an end to it all. He was the same age as I. Regardless of location, it gave me a glimpse of our interdependence in all its fragility and on full display. Even when isolated, we never truly are.But equally important was the little stuff.As someone who is physically affectionate and has a deep need for not-necessarily-sexual physical contact – such as hugging, cuddling or the occasional touch, and no means to meeting these – being alone taught me to learn, painfully, to be comfortable with being alone by myself.When I realized what was missing, it stirred in me a memory from my recent past. One day, when I was leaving after having met someone I knew, they just extended their arms for a hug, like a child would. Of course I hugged them. But as even the simplest of things can seem to someone deprived of them, it struck me as a sort of special ability, one that I lacked. I remember thinking, this is so beautiful, that people are able to do that – reach out and have their needs met. I am convinced that they have been able to do that since they were children, because it came so naturally to them, and that I wasn’t able to because it had never been that way for me growing up. I wondered whether this was something I might be able to change.Being alone taught me about love. And that the love of people – even thousands of miles away – whether family or friends, partners, acquaintances, comrades or colleagues, is all transmitted and can sustain you. I, who rarely called my parents before, began calling them frequently. It became a daily ritual, and one that I looked forward to. Having had my life pared down to the very bones made me value and cherish everyone who was connected to it so much more. I spent more time talking to my flatmate, and sharing the occasional meal or movie night became something far more special and invigorating than before. I had always been in the habit of checking in on friends I had not met for the longest time, but it began to take on a new significance when so many were grappling with mental health issues.I learned that there is love of all shapes and sizes to be shared in all manner of ways. It has taught me of the different ways there are of needing and being there for each other. It taught me to seek companionship with people wherever they are and where they are at in the moment and to the extent they are comfortable with, whether that is physical or virtual. You never want to impose on people, but especially when everyone is struggling with this collective trauma and the ensuing stress, to let people be unless they express or demonstrate a need for you or your company is a learning in emotional humility. Earlier I would sometimes wonder whether I was the only one that struggled with this, but seeing everyone struggling together allowed me to see the conflicts we experience in the light of our shared needs.During this period of intense reflection I was reminded of the words of a practitioner of Zen Buddhism living in town. He recalled his master telling him to be wary of two things: don't collect money [or material things], and don't collect people. Because I keep ticket stubs, plastic covers and receipts and can feel sentimentally attached to the smallest of things not for their material value but for their having been attached to a moment in life, the first is not simple. (I might have a hoarding problem.) But tougher still is the second. How do we not collect people in life? I can understand the wisdom in not wanting to collect a following or entourage and such (listen up, social media users), but the people who come into our lives in whatever way big or small – why is it so much easier for some to let go than it is for others? Let me just say that I would have disappointed the Zen master.As you grow older, life certainly teaches you that you have to let people go. But in the beginning alone-ness also struck me as a somewhat violent thing to do to yourself. Are some people more attuned to and accepting of the metaphor of each person being a satellite, encased in their own little shell and hurtling through space and occasionally passing close by others? Are people with stronger ties to community never really alone, and therefore more readily able to be physically alone? Do some of us need community, in all different senses of the word, more than others who are satisfied in their isolation and don’t experience it as loneliness? Is it really the balance of the shared (community) life and the personal (private) life that most of our pre-Covid lives had reached that keeps things on even keel? My thoughts were inundated with these reflections, and any answers that came forth were untested.

I, who rarely called my parents before, began calling them frequently. It became a daily ritual, and one that I looked forward to. Having had my life pared down to the very bones made me value and cherish everyone who was connected to it so much more. I spent more time talking to my flatmate, and sharing the occasional meal or movie night became something far more special and invigorating than before. I had always been in the habit of checking in on friends I had not met for the longest time, but it began to take on a new significance when so many were grappling with mental health issues.I learned that there is love of all shapes and sizes to be shared in all manner of ways. It has taught me of the different ways there are of needing and being there for each other. It taught me to seek companionship with people wherever they are and where they are at in the moment and to the extent they are comfortable with, whether that is physical or virtual. You never want to impose on people, but especially when everyone is struggling with this collective trauma and the ensuing stress, to let people be unless they express or demonstrate a need for you or your company is a learning in emotional humility. Earlier I would sometimes wonder whether I was the only one that struggled with this, but seeing everyone struggling together allowed me to see the conflicts we experience in the light of our shared needs.During this period of intense reflection I was reminded of the words of a practitioner of Zen Buddhism living in town. He recalled his master telling him to be wary of two things: don't collect money [or material things], and don't collect people. Because I keep ticket stubs, plastic covers and receipts and can feel sentimentally attached to the smallest of things not for their material value but for their having been attached to a moment in life, the first is not simple. (I might have a hoarding problem.) But tougher still is the second. How do we not collect people in life? I can understand the wisdom in not wanting to collect a following or entourage and such (listen up, social media users), but the people who come into our lives in whatever way big or small – why is it so much easier for some to let go than it is for others? Let me just say that I would have disappointed the Zen master.As you grow older, life certainly teaches you that you have to let people go. But in the beginning alone-ness also struck me as a somewhat violent thing to do to yourself. Are some people more attuned to and accepting of the metaphor of each person being a satellite, encased in their own little shell and hurtling through space and occasionally passing close by others? Are people with stronger ties to community never really alone, and therefore more readily able to be physically alone? Do some of us need community, in all different senses of the word, more than others who are satisfied in their isolation and don’t experience it as loneliness? Is it really the balance of the shared (community) life and the personal (private) life that most of our pre-Covid lives had reached that keeps things on even keel? My thoughts were inundated with these reflections, and any answers that came forth were untested.  I also learned something new about work. How certain kinds of work by their very nature (like the work some of us as researchers or writers do) can isolate you, take you deeper within to make you seem almost self-enclosed. But when there is no longer a social scaffolding to support you, the isolation is doubly felt. It might make it more comfortable for you to be on your own because the work itself, we like to believe, is worth something and its value enduring. On the flipside, does it also give you a deluded, inflated sense of your own worth? After a long period in which I was unable to bring myself to work, I grappled both with the sacrifices that this life calls for and the privilege of doing the sort of work that you could carry on with in these times. I saw around me people whom the isolation didn’t affect much in any obvious way. I know many who were perfectly happy being alone before and some have even come to enjoy having to see less of people. We have also discovered ways of doing without what was superfluous to us both as individuals and as an aggregate, granting that a lot of this comes with privilege. Are we all wired differently, or does the situation force us to adapt?Speaking for myself, I continue to find enforced isolation something I cannot do to myself in good conscience. But looking back now, I see that maybe, like a person going through withdrawal, I was also building endurance all along for something else: to be alone for longer periods. Is this what we call resilience?If one must reflect and grow, then this is as good or bad a circumstance to do that as any. It may or may not leave you changed, but there is a lot to learn. And it is not over yet.It’s been over five months since the weekend in March when the pandemic was declared, and a month since I returned home to all its warmth and the physical company of people I love. I value them more. I value our time spent together a lot more because I have yearned for it for half a year. I value personal sacrifices for collective well-being and solidarity in the face of danger. I value us all. The first time I went out to be among a crowd of people was for a Black Lives Matter protest. Despite the initial trepidation, it was heartening to see people wearing cloth masks out in numbers, with volunteers carrying sanitizers bobbing in and out amongst us. Even as we dealt with this new scourge, people had been facing epidemics less pathogenic, but as pathological, and battling those could not wait. At the end of the protest, a group of young people took to the streets dancing and their joy was infectious. There were things that were important enough for us to start easing the norms of social isolation. Navdeep has made one documentary, and finds that he enjoys research in media and film history more, for now. He just completed a master’s thesis on international non-theatrical sponsored film programs in post-independence India and is working on converting it into a form that fits people’s attention spans. He is a founding member of the Bi Collective Delhi. Sukh Mehak Kaur (BFA, MVA) is a comix artist and illustrator based in Ropar, Punjab. She is currently pursuing her goals to become a children's illustrator.

I also learned something new about work. How certain kinds of work by their very nature (like the work some of us as researchers or writers do) can isolate you, take you deeper within to make you seem almost self-enclosed. But when there is no longer a social scaffolding to support you, the isolation is doubly felt. It might make it more comfortable for you to be on your own because the work itself, we like to believe, is worth something and its value enduring. On the flipside, does it also give you a deluded, inflated sense of your own worth? After a long period in which I was unable to bring myself to work, I grappled both with the sacrifices that this life calls for and the privilege of doing the sort of work that you could carry on with in these times. I saw around me people whom the isolation didn’t affect much in any obvious way. I know many who were perfectly happy being alone before and some have even come to enjoy having to see less of people. We have also discovered ways of doing without what was superfluous to us both as individuals and as an aggregate, granting that a lot of this comes with privilege. Are we all wired differently, or does the situation force us to adapt?Speaking for myself, I continue to find enforced isolation something I cannot do to myself in good conscience. But looking back now, I see that maybe, like a person going through withdrawal, I was also building endurance all along for something else: to be alone for longer periods. Is this what we call resilience?If one must reflect and grow, then this is as good or bad a circumstance to do that as any. It may or may not leave you changed, but there is a lot to learn. And it is not over yet.It’s been over five months since the weekend in March when the pandemic was declared, and a month since I returned home to all its warmth and the physical company of people I love. I value them more. I value our time spent together a lot more because I have yearned for it for half a year. I value personal sacrifices for collective well-being and solidarity in the face of danger. I value us all. The first time I went out to be among a crowd of people was for a Black Lives Matter protest. Despite the initial trepidation, it was heartening to see people wearing cloth masks out in numbers, with volunteers carrying sanitizers bobbing in and out amongst us. Even as we dealt with this new scourge, people had been facing epidemics less pathogenic, but as pathological, and battling those could not wait. At the end of the protest, a group of young people took to the streets dancing and their joy was infectious. There were things that were important enough for us to start easing the norms of social isolation. Navdeep has made one documentary, and finds that he enjoys research in media and film history more, for now. He just completed a master’s thesis on international non-theatrical sponsored film programs in post-independence India and is working on converting it into a form that fits people’s attention spans. He is a founding member of the Bi Collective Delhi. Sukh Mehak Kaur (BFA, MVA) is a comix artist and illustrator based in Ropar, Punjab. She is currently pursuing her goals to become a children's illustrator.