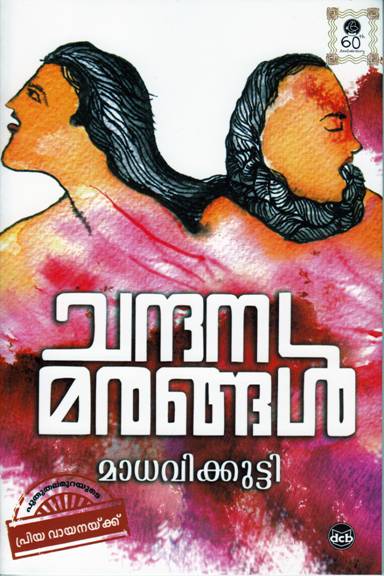

It’s Pride Month, and we get that feeling that it’s time for another zabardast AOI reading list (because books are cool and groovy, opening up whole new worlds and bringing to new life our familiar worlds). We know you loved our earlier reading list of queer books from India. But you are going to love this list even more because here’s a new list of queer books in various Indian languages so that we can discover new works by writers in our mothertongues, fathertongues, bestfriendtongues, and next-door-neighbourtongues.So banni, vaange, aaiye – and dive in!Chandana Marangal (1988) by Kamala Das – MalayalamThe novella Chandana Marangal, Malayalam for “Sandal Trees”, follows the relationship between Sheela, a girl from a well-off family, and Kalyanikutty, a girl from a poor family, who fall in love as teenagers. When their families find out, they try to marry them off to men, and on Sheela’s wedding day, Kalyani suggests running away. (Do they? Aha! We’re not going to tell you so easily!) We see the two women as they study medicine and grow older, contemplating their love and the social structures that try to prise them apart.But okay, we’ll tell you this much: this story has powerful, sensual descriptions of lesbian desire (it is a story by Kamal Das, after all, who caused something of an earthquake in Kerala in the 1970s, when her autobiography Enthe Katha, with its description of sexuality and same-sex love, came out). And here’s a clue about the title: the sandal trees that the story refers to are connected to Kalyani, who is described as having skin the colour of sandalwood. Mohanaswamy (2013) by Vasudhendra – KannadaThe stories in this book follow the journey of Mohanaswamy, a gay man navigating the worlds of love, loss, caste, class, and sexuality, and navigating the world quite literally, as we see him across geographical landscapes, from small town Karnataka to Mt Kilimanjaro.This story began in 2011 as a well-received 6,500 word story published under a pseudonym in Desha Kala, a Kannada literary magazine. In 2013, it resulted in a longer work – a collection of stories published under the author’s real name, Vasudhendra, and received widespread critical acclaim.Critic SR Vijayshankar credits Mohanaswamy with opening up space for a new literary genre in Kannada, and others have credited the book with introducing more openness towards queer people in Karnataka, citing other queer-themed Kannada literary works and films that were produced in its aftermath.

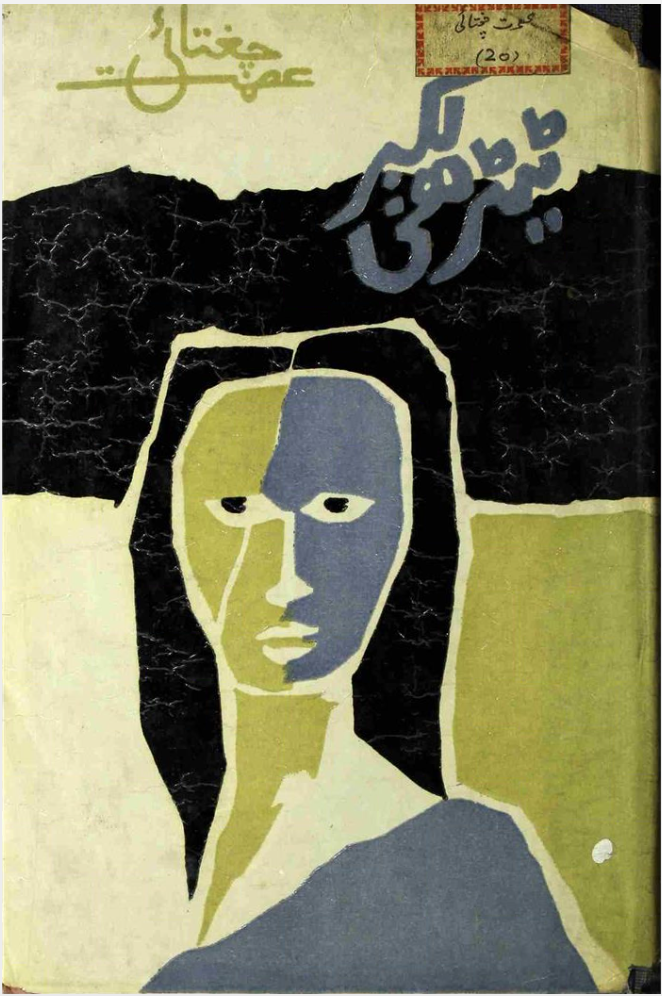

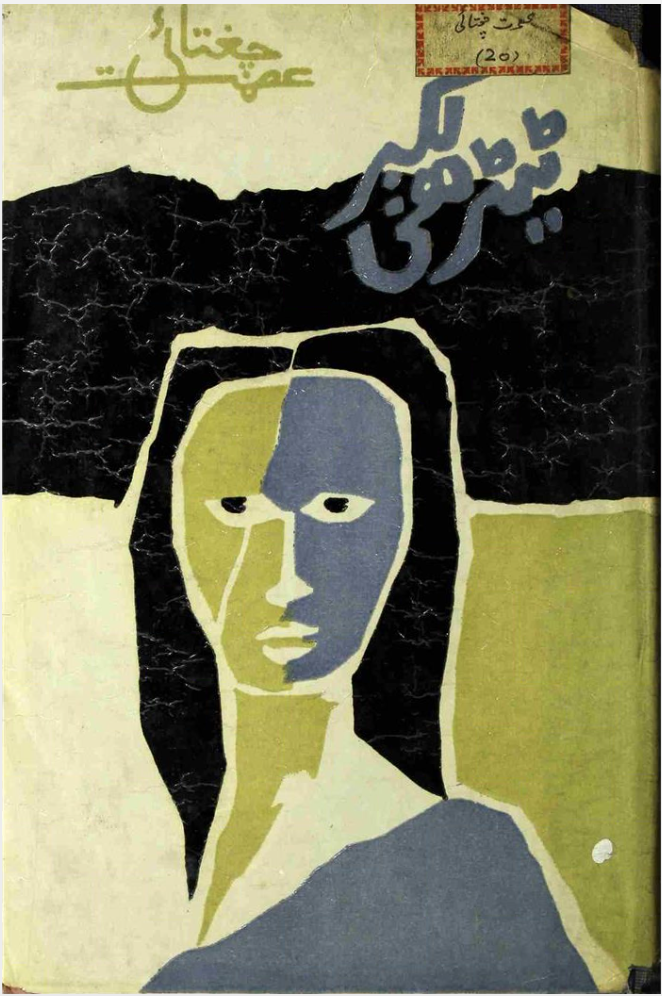

Mohanaswamy (2013) by Vasudhendra – KannadaThe stories in this book follow the journey of Mohanaswamy, a gay man navigating the worlds of love, loss, caste, class, and sexuality, and navigating the world quite literally, as we see him across geographical landscapes, from small town Karnataka to Mt Kilimanjaro.This story began in 2011 as a well-received 6,500 word story published under a pseudonym in Desha Kala, a Kannada literary magazine. In 2013, it resulted in a longer work – a collection of stories published under the author’s real name, Vasudhendra, and received widespread critical acclaim.Critic SR Vijayshankar credits Mohanaswamy with opening up space for a new literary genre in Kannada, and others have credited the book with introducing more openness towards queer people in Karnataka, citing other queer-themed Kannada literary works and films that were produced in its aftermath. Lihaaf (1942) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduBegum Jan, a prisoner in the rich Muslim household that she married into, finds that her husband “tucked her away in the house with his other possessions and promptly forgot her.” But in this Urdu short story, we don’t see her wither away. Begum Jan’s lihaaf (quilt) cannot keep her warm, but she finds warmth elsewhere – with her housemaid Rabbu, whose vigorous oil massages awaken something new within her.Chughtai was charged with obscenity for writing Lihaaf, although the story never makes the lesbian relationship explicit, and later said in her memoir that it had given her so much notoriety that it had overshadowed all of her other writing, including the quasi-autobiographical Tedhi Lakeer – which also includes queer relationships. The charges were dropped eventually, and Lihaaf remains one of the most well-known Indian works of lesbian erotic fiction, still open to new interpretations (including undertones of child sexual abuse in Begum Jan’s creepy treatment of the 9-year-old narrator). The story was also revisited in the 2014 film Dedh Ishqiya.

Lihaaf (1942) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduBegum Jan, a prisoner in the rich Muslim household that she married into, finds that her husband “tucked her away in the house with his other possessions and promptly forgot her.” But in this Urdu short story, we don’t see her wither away. Begum Jan’s lihaaf (quilt) cannot keep her warm, but she finds warmth elsewhere – with her housemaid Rabbu, whose vigorous oil massages awaken something new within her.Chughtai was charged with obscenity for writing Lihaaf, although the story never makes the lesbian relationship explicit, and later said in her memoir that it had given her so much notoriety that it had overshadowed all of her other writing, including the quasi-autobiographical Tedhi Lakeer – which also includes queer relationships. The charges were dropped eventually, and Lihaaf remains one of the most well-known Indian works of lesbian erotic fiction, still open to new interpretations (including undertones of child sexual abuse in Begum Jan’s creepy treatment of the 9-year-old narrator). The story was also revisited in the 2014 film Dedh Ishqiya. Vidupattavai (2018) by Gireesh – TamilThis contemporary collection of writing uses a mix of forms – poetry, short fiction, and non-fiction responding to homophobia, to centre the Tamil gay voice.In one of the poems from this collection, the narrator talks about trying to walk “the man walk” – the straight man walk – and he knows he’s being watched by a group of men at a table. Step by excruciating step, he makes an effort to change his posture, change his gait, as he crosses the room. The poem (in the English version translated by Sheiji Tadokoro) ends with the realisation that the struggle has been for nothing:I almost reached the doorsWith a triumphant smileI push the glass door, whereI see in reflections;you all are laughing behind meAgain, I miserably failedGireesh’s work focuses on what it’s like to be gay in Chennai, and serves as a weapon, in his words, against the violence and oppression he faced.

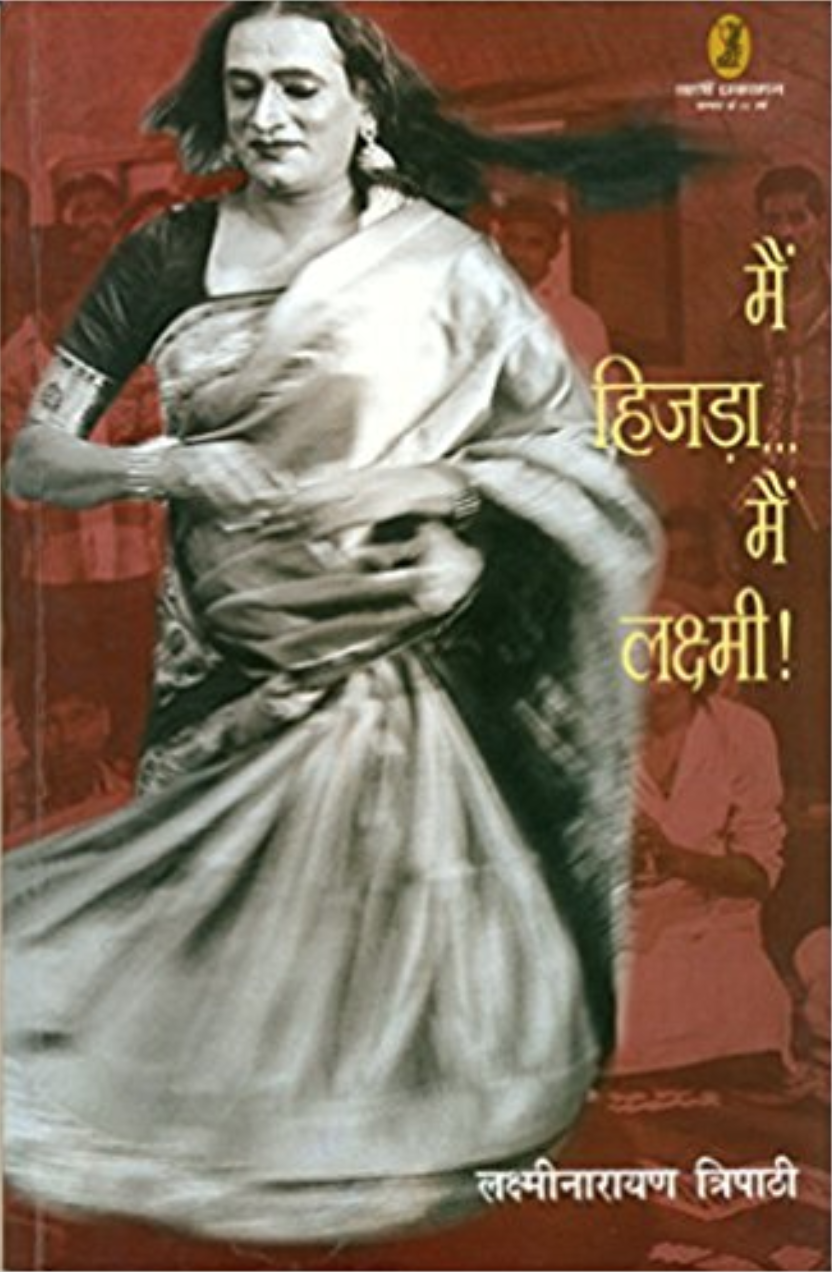

Vidupattavai (2018) by Gireesh – TamilThis contemporary collection of writing uses a mix of forms – poetry, short fiction, and non-fiction responding to homophobia, to centre the Tamil gay voice.In one of the poems from this collection, the narrator talks about trying to walk “the man walk” – the straight man walk – and he knows he’s being watched by a group of men at a table. Step by excruciating step, he makes an effort to change his posture, change his gait, as he crosses the room. The poem (in the English version translated by Sheiji Tadokoro) ends with the realisation that the struggle has been for nothing:I almost reached the doorsWith a triumphant smileI push the glass door, whereI see in reflections;you all are laughing behind meAgain, I miserably failedGireesh’s work focuses on what it’s like to be gay in Chennai, and serves as a weapon, in his words, against the violence and oppression he faced. Me Hijra…Me Laxmi (2012) by Laxmi Narayan Tripathi – MarathiLaxmi, an activist, actor and dancer, takes you through her life in this memoir – both the painful parts and the joyous ones. We see her as a young boy, suffering abuse and confused about sexuality; later, working as a dancer and choreographer, and eventually deciding to become a hijra. The book is as much a document of her life as it is a work of activism, and Laxmi often addresses the reader directly, assuring them that hijras are no different from the average person, and demanding that hijras be taken seriously.In Me Hijra…Me Laxmi, written with Vaishali Rode, Laxmi cautions a number of things: one is that there’s much more to her than what is contained in the covers of her book. Another is that all your questions about hijras will not be answered in just a few pages. But what this memoir by a woman who Salman Rushdie described as “a force of nature” does assure you of is the beauty of desire, fluid identities, doing what you love, and being true to oneself.

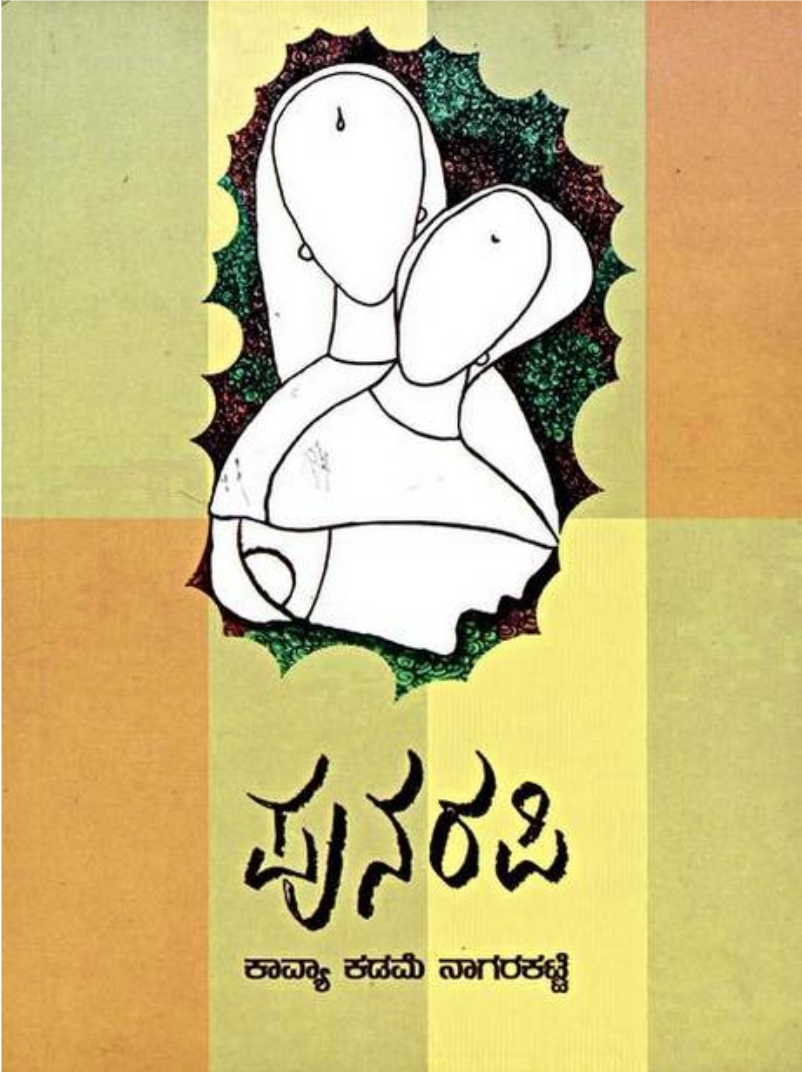

Me Hijra…Me Laxmi (2012) by Laxmi Narayan Tripathi – MarathiLaxmi, an activist, actor and dancer, takes you through her life in this memoir – both the painful parts and the joyous ones. We see her as a young boy, suffering abuse and confused about sexuality; later, working as a dancer and choreographer, and eventually deciding to become a hijra. The book is as much a document of her life as it is a work of activism, and Laxmi often addresses the reader directly, assuring them that hijras are no different from the average person, and demanding that hijras be taken seriously.In Me Hijra…Me Laxmi, written with Vaishali Rode, Laxmi cautions a number of things: one is that there’s much more to her than what is contained in the covers of her book. Another is that all your questions about hijras will not be answered in just a few pages. But what this memoir by a woman who Salman Rushdie described as “a force of nature” does assure you of is the beauty of desire, fluid identities, doing what you love, and being true to oneself. Punarapi (2017) by Kavya Kadame Nagarakatte – KannadaIn her first novel, award-winning young poet Kavya Kadame tells the story of Asma and Anusha who come from very different backgrounds and find themselves madly attracted to each other. Kadame has said that the idea for her novel grew out of reading Mohanaswamy and Julian Barnes’ Sense of An Ending. Punarapi has been admired for its beautiful prose and earnest young heroines.

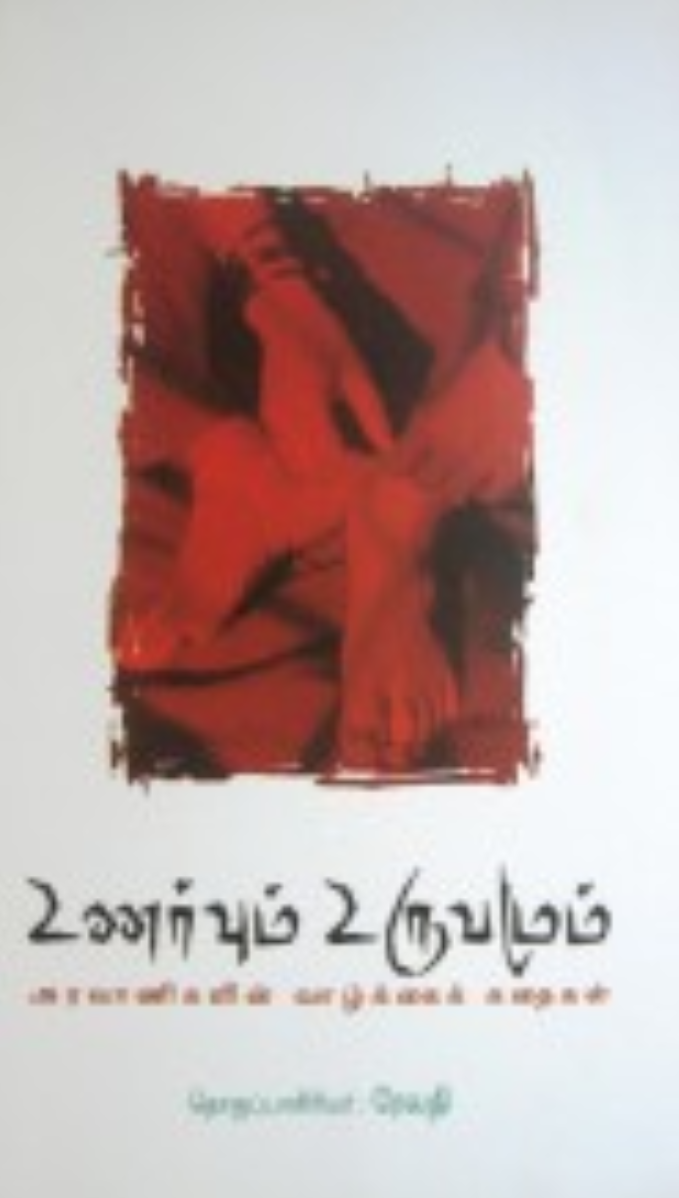

Punarapi (2017) by Kavya Kadame Nagarakatte – KannadaIn her first novel, award-winning young poet Kavya Kadame tells the story of Asma and Anusha who come from very different backgrounds and find themselves madly attracted to each other. Kadame has said that the idea for her novel grew out of reading Mohanaswamy and Julian Barnes’ Sense of An Ending. Punarapi has been admired for its beautiful prose and earnest young heroines. Chocolate (1927) by Ugra – HindiUgra was the pseudonym of the writer Pandey Bechan Sharma, a social reformer and nationalist. In Same-Sex Love in India, Ruth Vanita writes that Ugra “tends toward the didactic” in his fiction and had a reputation for inciting controversy. After a short story he published in 1924 called Chocolate caused uproar for its depiction of homosexuality, he wrote four more stories on the subject and published them as a collection in 1927. In the original story, he depicts a young man’s desire for an adolescent boy – to whom the term “chocolate” refers. They end up kissing passionately, and in the story, one of the characters invokes historical figures from Socrates and Shakespeare to Oscar Wilde to make the case that homosexuality is natural. But the story isn’t exactly sympathetic to homosexuality: Ugra also writes, “‘Chocolate’ is the name for those innocent, tender and beautiful boys of the country, whom society’s demons push into the mouth of ruin to quench their own lusts.” Love doesn’t end well in his queer stories, and although Vanita points out the ambivalence of his characterisations, Ugra (who was accused of being gay himself) claimed these tales were meant to expose homosexuality so that it could be addressed. Ultimately, Chocolate had an interesting effect: it led to public conversations and debate about homosexuality. Unarvum Uruvamum (2004) by A Revathi – TamilWritten in Tamil by Revathi, a Bangalore-based transgender activist, this book paints a portrait of hijra lives in South India (the book’s title translates loosely to “Feelings of the Entire Body”). The stories in this book were the result of her field studies and interviews with hijras in Tamil Nadu.In interviews, Revathi has said that she found it hard to get hijras to open up to her about their lives while working on this book, and that even when they did, she sometimes hesitated to include everything they said because it felt like an intrusion into someone else’s life. That, coupled with inspiration that she drew from reading Dalit writer Bama’s Karukku, led her to eventually write about herself (The Truth About Me – A Hijra Life Story, which hasn’t yet been published in Tamil), so that she could “talk about the complexity of our lives” and “fill in the many gaps” she had found in Unarvum Uruvamam.

Chocolate (1927) by Ugra – HindiUgra was the pseudonym of the writer Pandey Bechan Sharma, a social reformer and nationalist. In Same-Sex Love in India, Ruth Vanita writes that Ugra “tends toward the didactic” in his fiction and had a reputation for inciting controversy. After a short story he published in 1924 called Chocolate caused uproar for its depiction of homosexuality, he wrote four more stories on the subject and published them as a collection in 1927. In the original story, he depicts a young man’s desire for an adolescent boy – to whom the term “chocolate” refers. They end up kissing passionately, and in the story, one of the characters invokes historical figures from Socrates and Shakespeare to Oscar Wilde to make the case that homosexuality is natural. But the story isn’t exactly sympathetic to homosexuality: Ugra also writes, “‘Chocolate’ is the name for those innocent, tender and beautiful boys of the country, whom society’s demons push into the mouth of ruin to quench their own lusts.” Love doesn’t end well in his queer stories, and although Vanita points out the ambivalence of his characterisations, Ugra (who was accused of being gay himself) claimed these tales were meant to expose homosexuality so that it could be addressed. Ultimately, Chocolate had an interesting effect: it led to public conversations and debate about homosexuality. Unarvum Uruvamum (2004) by A Revathi – TamilWritten in Tamil by Revathi, a Bangalore-based transgender activist, this book paints a portrait of hijra lives in South India (the book’s title translates loosely to “Feelings of the Entire Body”). The stories in this book were the result of her field studies and interviews with hijras in Tamil Nadu.In interviews, Revathi has said that she found it hard to get hijras to open up to her about their lives while working on this book, and that even when they did, she sometimes hesitated to include everything they said because it felt like an intrusion into someone else’s life. That, coupled with inspiration that she drew from reading Dalit writer Bama’s Karukku, led her to eventually write about herself (The Truth About Me – A Hijra Life Story, which hasn’t yet been published in Tamil), so that she could “talk about the complexity of our lives” and “fill in the many gaps” she had found in Unarvum Uruvamam. Prateeksha (1962) by Rajendra Yadav – Hindi“Ever since Harsh has come, Nanda seems to have gone crazy. She is not on this earth, she is floating in the air, above time. She scarcely remembers that Geeta exists .... How quickly this girl changes color! Doesn't take her a minute!”That little snippet was from Ruth Vanita’s English translation. So here’s the backstory: Geeta lives with Nanda. Nanda has a boyfriend called Harsh who comes to stay with her, and Geeta is annoyed. She feels like she has to look after them both, even though she’s irritated that they are sleeping together, and can’t wait for Harsh to leave. But what are these feelings that she has for Nanda, with her stylish clothes and pretty face? Prateeksha depicts the lesbian relationship between its characters with frankness, tenderness and delicious detail. Cobalt Blue (2000) by Sachin Kundalkar – MarathiThe Joshi household had a new paying guest. He paid his rent on time. Tanay found him perfect. “We hit it off immediately; neither of us liked the kind of girl who would sing syrupy light classical music—bhav geet; nor the kind of boy who would wear banians with sleeves.” But what happened when Tanay’s sister Anuja found him perfect too? This is the premise of the stunning Marathi novel that award-winning filmmaker Sachin Kundalkar wrote when he was a mere 22. This is an elegant tale of a stranger who arrives in a quiet household and breaks its conventions and breaks hearts.

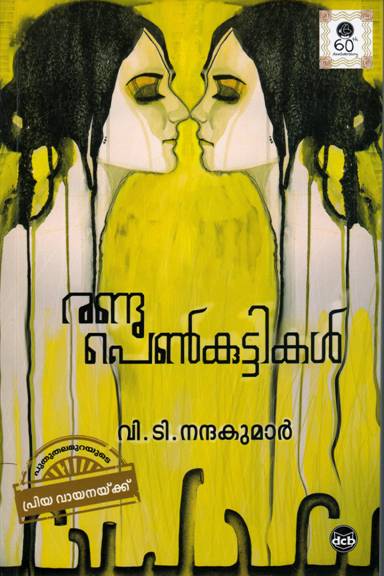

Prateeksha (1962) by Rajendra Yadav – Hindi“Ever since Harsh has come, Nanda seems to have gone crazy. She is not on this earth, she is floating in the air, above time. She scarcely remembers that Geeta exists .... How quickly this girl changes color! Doesn't take her a minute!”That little snippet was from Ruth Vanita’s English translation. So here’s the backstory: Geeta lives with Nanda. Nanda has a boyfriend called Harsh who comes to stay with her, and Geeta is annoyed. She feels like she has to look after them both, even though she’s irritated that they are sleeping together, and can’t wait for Harsh to leave. But what are these feelings that she has for Nanda, with her stylish clothes and pretty face? Prateeksha depicts the lesbian relationship between its characters with frankness, tenderness and delicious detail. Cobalt Blue (2000) by Sachin Kundalkar – MarathiThe Joshi household had a new paying guest. He paid his rent on time. Tanay found him perfect. “We hit it off immediately; neither of us liked the kind of girl who would sing syrupy light classical music—bhav geet; nor the kind of boy who would wear banians with sleeves.” But what happened when Tanay’s sister Anuja found him perfect too? This is the premise of the stunning Marathi novel that award-winning filmmaker Sachin Kundalkar wrote when he was a mere 22. This is an elegant tale of a stranger who arrives in a quiet household and breaks its conventions and breaks hearts. Randu Penkutikkal (1974) by VT Nandakumar – MalayalamVT Nandakumar’s Malayalam novel “Two Girls” first appeared in serialised form in Chitrakarthika Weekly. The novel traces the relationship between Girija, a schoolgirl who wants to be strong like the boy next door and kiss a beautiful girl, and who falls hard for Kokila, the gorgeous new student at her school. In his introduction to the second edition of the novel, Nandakumar makes an unusual plea: “Lesbianism – which means a love affair between women – is now ubiquitous. In my opinion this passion is likely to be widespread among the young women of Kerala who, by nature, are extraordinarily sensitive. Such relationships have some healthy and positive potential hence they are important. […] Let me conclude by praying for the growth and prosperity of lesbianism.”

Randu Penkutikkal (1974) by VT Nandakumar – MalayalamVT Nandakumar’s Malayalam novel “Two Girls” first appeared in serialised form in Chitrakarthika Weekly. The novel traces the relationship between Girija, a schoolgirl who wants to be strong like the boy next door and kiss a beautiful girl, and who falls hard for Kokila, the gorgeous new student at her school. In his introduction to the second edition of the novel, Nandakumar makes an unusual plea: “Lesbianism – which means a love affair between women – is now ubiquitous. In my opinion this passion is likely to be widespread among the young women of Kerala who, by nature, are extraordinarily sensitive. Such relationships have some healthy and positive potential hence they are important. […] Let me conclude by praying for the growth and prosperity of lesbianism.” Mitrachi Goshta (1974) by Vijay Tendulkar – Marathi‘Mitra’s Story’, a Marathi play first performed in 1981 with Rohini Hattangadi in the lead, follows the lives of three college students – Mitra, Bapu and Nanda. Mitra falls in love with Nama when they act in a play together. Bapu, Mitra’s friend, helps the two women out and lets them meet in his room when they want to… umm… get close. But things are complicated by the fact that Nama has a rowdy boyfriend, and that Nama sleeps with both Mitra and her boyfriend. A local newspaper publishes a story about the two women, revealing their relationship. Things begin to spiral and take a tragic turn.Annoyingly, the relationship between the two women is narrated to the audience by Bapu, a man, and the story ends badly for Mitra, like a morality tale in which those attempting to live outside society’s norms have to be punished. But Mitrachi Goshta is considered significant as Tendulkar was one of India’s best known playwrights, and the play was performed within the mainstream, raising homosexuality as a mainstream topic. Tedhi Lakeer (1945) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduThis novel deals with the lives of middle-class Muslim women using everyday language, a style that Salim Kidwai points out was not used in Urdu prose before Chughtai. Kidwai also writes that this is “the first important Urdu novel on Muslim women; it shows sex as an instrument both of women's oppression and of their rebellion.”We see two generations of women in the novel – the older one consists of women in purdah, whose choices and exposure to the world are limited. The younger women, Shamman (the protagonist) and her friends, lead lives less cloistered, but in a country heading towards independence, freedom isn’t quite theirs yet. What all the women do have, though, are their relationships with each other. In the novel’s description of Shamman’s childhood, in which anyone who went to an all-girls’ school might recognise their own little horny selves and fellow students, we see Shamman infatuated with her teacher, Miss Charan, and fantasise about the older woman, just as we see Shamman become the object of desire for other girls her age.

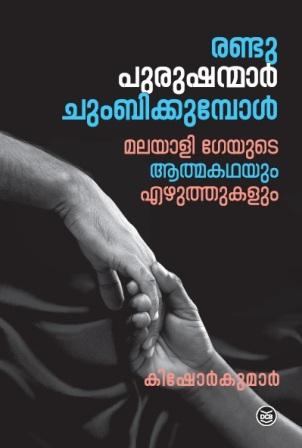

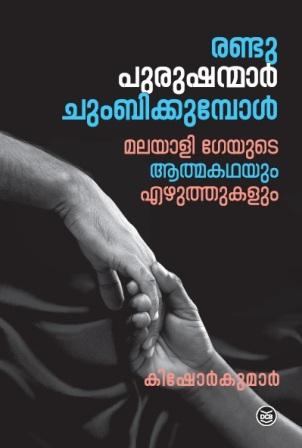

Mitrachi Goshta (1974) by Vijay Tendulkar – Marathi‘Mitra’s Story’, a Marathi play first performed in 1981 with Rohini Hattangadi in the lead, follows the lives of three college students – Mitra, Bapu and Nanda. Mitra falls in love with Nama when they act in a play together. Bapu, Mitra’s friend, helps the two women out and lets them meet in his room when they want to… umm… get close. But things are complicated by the fact that Nama has a rowdy boyfriend, and that Nama sleeps with both Mitra and her boyfriend. A local newspaper publishes a story about the two women, revealing their relationship. Things begin to spiral and take a tragic turn.Annoyingly, the relationship between the two women is narrated to the audience by Bapu, a man, and the story ends badly for Mitra, like a morality tale in which those attempting to live outside society’s norms have to be punished. But Mitrachi Goshta is considered significant as Tendulkar was one of India’s best known playwrights, and the play was performed within the mainstream, raising homosexuality as a mainstream topic. Tedhi Lakeer (1945) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduThis novel deals with the lives of middle-class Muslim women using everyday language, a style that Salim Kidwai points out was not used in Urdu prose before Chughtai. Kidwai also writes that this is “the first important Urdu novel on Muslim women; it shows sex as an instrument both of women's oppression and of their rebellion.”We see two generations of women in the novel – the older one consists of women in purdah, whose choices and exposure to the world are limited. The younger women, Shamman (the protagonist) and her friends, lead lives less cloistered, but in a country heading towards independence, freedom isn’t quite theirs yet. What all the women do have, though, are their relationships with each other. In the novel’s description of Shamman’s childhood, in which anyone who went to an all-girls’ school might recognise their own little horny selves and fellow students, we see Shamman infatuated with her teacher, Miss Charan, and fantasise about the older woman, just as we see Shamman become the object of desire for other girls her age.  Randu Purushanmar Chumbikkumbol (2017) by Kishor Kumar – MalayalamThis collection of Malayalam writing, whose title translates to “When Two Men Kiss”, spans the author’s personal experiences as well as a collection of essays on a range of subjects related to being queer.The personal portion of the book contains an autobiography – Kumar, an IIT graduate from Kerala, documents his life’s journey within India and abroad. We learn about his family, career, and his life as a gay man at various stages. The rest of the book is an assortment of interviews and Kumar’s essays exploring a range of topics including art and literature, politics, and psychology.

Randu Purushanmar Chumbikkumbol (2017) by Kishor Kumar – MalayalamThis collection of Malayalam writing, whose title translates to “When Two Men Kiss”, spans the author’s personal experiences as well as a collection of essays on a range of subjects related to being queer.The personal portion of the book contains an autobiography – Kumar, an IIT graduate from Kerala, documents his life’s journey within India and abroad. We learn about his family, career, and his life as a gay man at various stages. The rest of the book is an assortment of interviews and Kumar’s essays exploring a range of topics including art and literature, politics, and psychology. Untitled story (1968) by Bhupen Khakhar – GujaratiMohanlal is a middle-aged, reticent man, with a wife named Manjari and two children. When the story begins, we think it’s a story about Manjari and her relationship with her childhood flame Ratilal. But it’s also about Mohanlal’s gay relationship with a peon. This story was first published in the 1960s in a magazine called Kriti.Khakhar was better known for his paintings than for his writing, and according to Timothy Hyman, was “celebrated for his startling, visionary images of homosexual love”. Khakhar, who lived from 1934 to 2003, was open about being gay, and about the homoerotic themes in his work. Want more? Follow these online spaces to learn about new writing in regional languages: Xukia, Gaylaxy, Queer Ink, and Queer Chennai Chronicles.

Untitled story (1968) by Bhupen Khakhar – GujaratiMohanlal is a middle-aged, reticent man, with a wife named Manjari and two children. When the story begins, we think it’s a story about Manjari and her relationship with her childhood flame Ratilal. But it’s also about Mohanlal’s gay relationship with a peon. This story was first published in the 1960s in a magazine called Kriti.Khakhar was better known for his paintings than for his writing, and according to Timothy Hyman, was “celebrated for his startling, visionary images of homosexual love”. Khakhar, who lived from 1934 to 2003, was open about being gay, and about the homoerotic themes in his work. Want more? Follow these online spaces to learn about new writing in regional languages: Xukia, Gaylaxy, Queer Ink, and Queer Chennai Chronicles.

Mohanaswamy (2013) by Vasudhendra – KannadaThe stories in this book follow the journey of Mohanaswamy, a gay man navigating the worlds of love, loss, caste, class, and sexuality, and navigating the world quite literally, as we see him across geographical landscapes, from small town Karnataka to Mt Kilimanjaro.This story began in 2011 as a well-received 6,500 word story published under a pseudonym in Desha Kala, a Kannada literary magazine. In 2013, it resulted in a longer work – a collection of stories published under the author’s real name, Vasudhendra, and received widespread critical acclaim.Critic SR Vijayshankar credits Mohanaswamy with opening up space for a new literary genre in Kannada, and others have credited the book with introducing more openness towards queer people in Karnataka, citing other queer-themed Kannada literary works and films that were produced in its aftermath.

Mohanaswamy (2013) by Vasudhendra – KannadaThe stories in this book follow the journey of Mohanaswamy, a gay man navigating the worlds of love, loss, caste, class, and sexuality, and navigating the world quite literally, as we see him across geographical landscapes, from small town Karnataka to Mt Kilimanjaro.This story began in 2011 as a well-received 6,500 word story published under a pseudonym in Desha Kala, a Kannada literary magazine. In 2013, it resulted in a longer work – a collection of stories published under the author’s real name, Vasudhendra, and received widespread critical acclaim.Critic SR Vijayshankar credits Mohanaswamy with opening up space for a new literary genre in Kannada, and others have credited the book with introducing more openness towards queer people in Karnataka, citing other queer-themed Kannada literary works and films that were produced in its aftermath. Lihaaf (1942) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduBegum Jan, a prisoner in the rich Muslim household that she married into, finds that her husband “tucked her away in the house with his other possessions and promptly forgot her.” But in this Urdu short story, we don’t see her wither away. Begum Jan’s lihaaf (quilt) cannot keep her warm, but she finds warmth elsewhere – with her housemaid Rabbu, whose vigorous oil massages awaken something new within her.Chughtai was charged with obscenity for writing Lihaaf, although the story never makes the lesbian relationship explicit, and later said in her memoir that it had given her so much notoriety that it had overshadowed all of her other writing, including the quasi-autobiographical Tedhi Lakeer – which also includes queer relationships. The charges were dropped eventually, and Lihaaf remains one of the most well-known Indian works of lesbian erotic fiction, still open to new interpretations (including undertones of child sexual abuse in Begum Jan’s creepy treatment of the 9-year-old narrator). The story was also revisited in the 2014 film Dedh Ishqiya.

Lihaaf (1942) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduBegum Jan, a prisoner in the rich Muslim household that she married into, finds that her husband “tucked her away in the house with his other possessions and promptly forgot her.” But in this Urdu short story, we don’t see her wither away. Begum Jan’s lihaaf (quilt) cannot keep her warm, but she finds warmth elsewhere – with her housemaid Rabbu, whose vigorous oil massages awaken something new within her.Chughtai was charged with obscenity for writing Lihaaf, although the story never makes the lesbian relationship explicit, and later said in her memoir that it had given her so much notoriety that it had overshadowed all of her other writing, including the quasi-autobiographical Tedhi Lakeer – which also includes queer relationships. The charges were dropped eventually, and Lihaaf remains one of the most well-known Indian works of lesbian erotic fiction, still open to new interpretations (including undertones of child sexual abuse in Begum Jan’s creepy treatment of the 9-year-old narrator). The story was also revisited in the 2014 film Dedh Ishqiya. Vidupattavai (2018) by Gireesh – TamilThis contemporary collection of writing uses a mix of forms – poetry, short fiction, and non-fiction responding to homophobia, to centre the Tamil gay voice.In one of the poems from this collection, the narrator talks about trying to walk “the man walk” – the straight man walk – and he knows he’s being watched by a group of men at a table. Step by excruciating step, he makes an effort to change his posture, change his gait, as he crosses the room. The poem (in the English version translated by Sheiji Tadokoro) ends with the realisation that the struggle has been for nothing:I almost reached the doorsWith a triumphant smileI push the glass door, whereI see in reflections;you all are laughing behind meAgain, I miserably failedGireesh’s work focuses on what it’s like to be gay in Chennai, and serves as a weapon, in his words, against the violence and oppression he faced.

Vidupattavai (2018) by Gireesh – TamilThis contemporary collection of writing uses a mix of forms – poetry, short fiction, and non-fiction responding to homophobia, to centre the Tamil gay voice.In one of the poems from this collection, the narrator talks about trying to walk “the man walk” – the straight man walk – and he knows he’s being watched by a group of men at a table. Step by excruciating step, he makes an effort to change his posture, change his gait, as he crosses the room. The poem (in the English version translated by Sheiji Tadokoro) ends with the realisation that the struggle has been for nothing:I almost reached the doorsWith a triumphant smileI push the glass door, whereI see in reflections;you all are laughing behind meAgain, I miserably failedGireesh’s work focuses on what it’s like to be gay in Chennai, and serves as a weapon, in his words, against the violence and oppression he faced. Me Hijra…Me Laxmi (2012) by Laxmi Narayan Tripathi – MarathiLaxmi, an activist, actor and dancer, takes you through her life in this memoir – both the painful parts and the joyous ones. We see her as a young boy, suffering abuse and confused about sexuality; later, working as a dancer and choreographer, and eventually deciding to become a hijra. The book is as much a document of her life as it is a work of activism, and Laxmi often addresses the reader directly, assuring them that hijras are no different from the average person, and demanding that hijras be taken seriously.In Me Hijra…Me Laxmi, written with Vaishali Rode, Laxmi cautions a number of things: one is that there’s much more to her than what is contained in the covers of her book. Another is that all your questions about hijras will not be answered in just a few pages. But what this memoir by a woman who Salman Rushdie described as “a force of nature” does assure you of is the beauty of desire, fluid identities, doing what you love, and being true to oneself.

Me Hijra…Me Laxmi (2012) by Laxmi Narayan Tripathi – MarathiLaxmi, an activist, actor and dancer, takes you through her life in this memoir – both the painful parts and the joyous ones. We see her as a young boy, suffering abuse and confused about sexuality; later, working as a dancer and choreographer, and eventually deciding to become a hijra. The book is as much a document of her life as it is a work of activism, and Laxmi often addresses the reader directly, assuring them that hijras are no different from the average person, and demanding that hijras be taken seriously.In Me Hijra…Me Laxmi, written with Vaishali Rode, Laxmi cautions a number of things: one is that there’s much more to her than what is contained in the covers of her book. Another is that all your questions about hijras will not be answered in just a few pages. But what this memoir by a woman who Salman Rushdie described as “a force of nature” does assure you of is the beauty of desire, fluid identities, doing what you love, and being true to oneself. Punarapi (2017) by Kavya Kadame Nagarakatte – KannadaIn her first novel, award-winning young poet Kavya Kadame tells the story of Asma and Anusha who come from very different backgrounds and find themselves madly attracted to each other. Kadame has said that the idea for her novel grew out of reading Mohanaswamy and Julian Barnes’ Sense of An Ending. Punarapi has been admired for its beautiful prose and earnest young heroines.

Punarapi (2017) by Kavya Kadame Nagarakatte – KannadaIn her first novel, award-winning young poet Kavya Kadame tells the story of Asma and Anusha who come from very different backgrounds and find themselves madly attracted to each other. Kadame has said that the idea for her novel grew out of reading Mohanaswamy and Julian Barnes’ Sense of An Ending. Punarapi has been admired for its beautiful prose and earnest young heroines. Chocolate (1927) by Ugra – HindiUgra was the pseudonym of the writer Pandey Bechan Sharma, a social reformer and nationalist. In Same-Sex Love in India, Ruth Vanita writes that Ugra “tends toward the didactic” in his fiction and had a reputation for inciting controversy. After a short story he published in 1924 called Chocolate caused uproar for its depiction of homosexuality, he wrote four more stories on the subject and published them as a collection in 1927. In the original story, he depicts a young man’s desire for an adolescent boy – to whom the term “chocolate” refers. They end up kissing passionately, and in the story, one of the characters invokes historical figures from Socrates and Shakespeare to Oscar Wilde to make the case that homosexuality is natural. But the story isn’t exactly sympathetic to homosexuality: Ugra also writes, “‘Chocolate’ is the name for those innocent, tender and beautiful boys of the country, whom society’s demons push into the mouth of ruin to quench their own lusts.” Love doesn’t end well in his queer stories, and although Vanita points out the ambivalence of his characterisations, Ugra (who was accused of being gay himself) claimed these tales were meant to expose homosexuality so that it could be addressed. Ultimately, Chocolate had an interesting effect: it led to public conversations and debate about homosexuality. Unarvum Uruvamum (2004) by A Revathi – TamilWritten in Tamil by Revathi, a Bangalore-based transgender activist, this book paints a portrait of hijra lives in South India (the book’s title translates loosely to “Feelings of the Entire Body”). The stories in this book were the result of her field studies and interviews with hijras in Tamil Nadu.In interviews, Revathi has said that she found it hard to get hijras to open up to her about their lives while working on this book, and that even when they did, she sometimes hesitated to include everything they said because it felt like an intrusion into someone else’s life. That, coupled with inspiration that she drew from reading Dalit writer Bama’s Karukku, led her to eventually write about herself (The Truth About Me – A Hijra Life Story, which hasn’t yet been published in Tamil), so that she could “talk about the complexity of our lives” and “fill in the many gaps” she had found in Unarvum Uruvamam.

Chocolate (1927) by Ugra – HindiUgra was the pseudonym of the writer Pandey Bechan Sharma, a social reformer and nationalist. In Same-Sex Love in India, Ruth Vanita writes that Ugra “tends toward the didactic” in his fiction and had a reputation for inciting controversy. After a short story he published in 1924 called Chocolate caused uproar for its depiction of homosexuality, he wrote four more stories on the subject and published them as a collection in 1927. In the original story, he depicts a young man’s desire for an adolescent boy – to whom the term “chocolate” refers. They end up kissing passionately, and in the story, one of the characters invokes historical figures from Socrates and Shakespeare to Oscar Wilde to make the case that homosexuality is natural. But the story isn’t exactly sympathetic to homosexuality: Ugra also writes, “‘Chocolate’ is the name for those innocent, tender and beautiful boys of the country, whom society’s demons push into the mouth of ruin to quench their own lusts.” Love doesn’t end well in his queer stories, and although Vanita points out the ambivalence of his characterisations, Ugra (who was accused of being gay himself) claimed these tales were meant to expose homosexuality so that it could be addressed. Ultimately, Chocolate had an interesting effect: it led to public conversations and debate about homosexuality. Unarvum Uruvamum (2004) by A Revathi – TamilWritten in Tamil by Revathi, a Bangalore-based transgender activist, this book paints a portrait of hijra lives in South India (the book’s title translates loosely to “Feelings of the Entire Body”). The stories in this book were the result of her field studies and interviews with hijras in Tamil Nadu.In interviews, Revathi has said that she found it hard to get hijras to open up to her about their lives while working on this book, and that even when they did, she sometimes hesitated to include everything they said because it felt like an intrusion into someone else’s life. That, coupled with inspiration that she drew from reading Dalit writer Bama’s Karukku, led her to eventually write about herself (The Truth About Me – A Hijra Life Story, which hasn’t yet been published in Tamil), so that she could “talk about the complexity of our lives” and “fill in the many gaps” she had found in Unarvum Uruvamam. Prateeksha (1962) by Rajendra Yadav – Hindi“Ever since Harsh has come, Nanda seems to have gone crazy. She is not on this earth, she is floating in the air, above time. She scarcely remembers that Geeta exists .... How quickly this girl changes color! Doesn't take her a minute!”That little snippet was from Ruth Vanita’s English translation. So here’s the backstory: Geeta lives with Nanda. Nanda has a boyfriend called Harsh who comes to stay with her, and Geeta is annoyed. She feels like she has to look after them both, even though she’s irritated that they are sleeping together, and can’t wait for Harsh to leave. But what are these feelings that she has for Nanda, with her stylish clothes and pretty face? Prateeksha depicts the lesbian relationship between its characters with frankness, tenderness and delicious detail. Cobalt Blue (2000) by Sachin Kundalkar – MarathiThe Joshi household had a new paying guest. He paid his rent on time. Tanay found him perfect. “We hit it off immediately; neither of us liked the kind of girl who would sing syrupy light classical music—bhav geet; nor the kind of boy who would wear banians with sleeves.” But what happened when Tanay’s sister Anuja found him perfect too? This is the premise of the stunning Marathi novel that award-winning filmmaker Sachin Kundalkar wrote when he was a mere 22. This is an elegant tale of a stranger who arrives in a quiet household and breaks its conventions and breaks hearts.

Prateeksha (1962) by Rajendra Yadav – Hindi“Ever since Harsh has come, Nanda seems to have gone crazy. She is not on this earth, she is floating in the air, above time. She scarcely remembers that Geeta exists .... How quickly this girl changes color! Doesn't take her a minute!”That little snippet was from Ruth Vanita’s English translation. So here’s the backstory: Geeta lives with Nanda. Nanda has a boyfriend called Harsh who comes to stay with her, and Geeta is annoyed. She feels like she has to look after them both, even though she’s irritated that they are sleeping together, and can’t wait for Harsh to leave. But what are these feelings that she has for Nanda, with her stylish clothes and pretty face? Prateeksha depicts the lesbian relationship between its characters with frankness, tenderness and delicious detail. Cobalt Blue (2000) by Sachin Kundalkar – MarathiThe Joshi household had a new paying guest. He paid his rent on time. Tanay found him perfect. “We hit it off immediately; neither of us liked the kind of girl who would sing syrupy light classical music—bhav geet; nor the kind of boy who would wear banians with sleeves.” But what happened when Tanay’s sister Anuja found him perfect too? This is the premise of the stunning Marathi novel that award-winning filmmaker Sachin Kundalkar wrote when he was a mere 22. This is an elegant tale of a stranger who arrives in a quiet household and breaks its conventions and breaks hearts. Randu Penkutikkal (1974) by VT Nandakumar – MalayalamVT Nandakumar’s Malayalam novel “Two Girls” first appeared in serialised form in Chitrakarthika Weekly. The novel traces the relationship between Girija, a schoolgirl who wants to be strong like the boy next door and kiss a beautiful girl, and who falls hard for Kokila, the gorgeous new student at her school. In his introduction to the second edition of the novel, Nandakumar makes an unusual plea: “Lesbianism – which means a love affair between women – is now ubiquitous. In my opinion this passion is likely to be widespread among the young women of Kerala who, by nature, are extraordinarily sensitive. Such relationships have some healthy and positive potential hence they are important. […] Let me conclude by praying for the growth and prosperity of lesbianism.”

Randu Penkutikkal (1974) by VT Nandakumar – MalayalamVT Nandakumar’s Malayalam novel “Two Girls” first appeared in serialised form in Chitrakarthika Weekly. The novel traces the relationship between Girija, a schoolgirl who wants to be strong like the boy next door and kiss a beautiful girl, and who falls hard for Kokila, the gorgeous new student at her school. In his introduction to the second edition of the novel, Nandakumar makes an unusual plea: “Lesbianism – which means a love affair between women – is now ubiquitous. In my opinion this passion is likely to be widespread among the young women of Kerala who, by nature, are extraordinarily sensitive. Such relationships have some healthy and positive potential hence they are important. […] Let me conclude by praying for the growth and prosperity of lesbianism.” Mitrachi Goshta (1974) by Vijay Tendulkar – Marathi‘Mitra’s Story’, a Marathi play first performed in 1981 with Rohini Hattangadi in the lead, follows the lives of three college students – Mitra, Bapu and Nanda. Mitra falls in love with Nama when they act in a play together. Bapu, Mitra’s friend, helps the two women out and lets them meet in his room when they want to… umm… get close. But things are complicated by the fact that Nama has a rowdy boyfriend, and that Nama sleeps with both Mitra and her boyfriend. A local newspaper publishes a story about the two women, revealing their relationship. Things begin to spiral and take a tragic turn.Annoyingly, the relationship between the two women is narrated to the audience by Bapu, a man, and the story ends badly for Mitra, like a morality tale in which those attempting to live outside society’s norms have to be punished. But Mitrachi Goshta is considered significant as Tendulkar was one of India’s best known playwrights, and the play was performed within the mainstream, raising homosexuality as a mainstream topic. Tedhi Lakeer (1945) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduThis novel deals with the lives of middle-class Muslim women using everyday language, a style that Salim Kidwai points out was not used in Urdu prose before Chughtai. Kidwai also writes that this is “the first important Urdu novel on Muslim women; it shows sex as an instrument both of women's oppression and of their rebellion.”We see two generations of women in the novel – the older one consists of women in purdah, whose choices and exposure to the world are limited. The younger women, Shamman (the protagonist) and her friends, lead lives less cloistered, but in a country heading towards independence, freedom isn’t quite theirs yet. What all the women do have, though, are their relationships with each other. In the novel’s description of Shamman’s childhood, in which anyone who went to an all-girls’ school might recognise their own little horny selves and fellow students, we see Shamman infatuated with her teacher, Miss Charan, and fantasise about the older woman, just as we see Shamman become the object of desire for other girls her age.

Mitrachi Goshta (1974) by Vijay Tendulkar – Marathi‘Mitra’s Story’, a Marathi play first performed in 1981 with Rohini Hattangadi in the lead, follows the lives of three college students – Mitra, Bapu and Nanda. Mitra falls in love with Nama when they act in a play together. Bapu, Mitra’s friend, helps the two women out and lets them meet in his room when they want to… umm… get close. But things are complicated by the fact that Nama has a rowdy boyfriend, and that Nama sleeps with both Mitra and her boyfriend. A local newspaper publishes a story about the two women, revealing their relationship. Things begin to spiral and take a tragic turn.Annoyingly, the relationship between the two women is narrated to the audience by Bapu, a man, and the story ends badly for Mitra, like a morality tale in which those attempting to live outside society’s norms have to be punished. But Mitrachi Goshta is considered significant as Tendulkar was one of India’s best known playwrights, and the play was performed within the mainstream, raising homosexuality as a mainstream topic. Tedhi Lakeer (1945) by Ismat Chughtai – UrduThis novel deals with the lives of middle-class Muslim women using everyday language, a style that Salim Kidwai points out was not used in Urdu prose before Chughtai. Kidwai also writes that this is “the first important Urdu novel on Muslim women; it shows sex as an instrument both of women's oppression and of their rebellion.”We see two generations of women in the novel – the older one consists of women in purdah, whose choices and exposure to the world are limited. The younger women, Shamman (the protagonist) and her friends, lead lives less cloistered, but in a country heading towards independence, freedom isn’t quite theirs yet. What all the women do have, though, are their relationships with each other. In the novel’s description of Shamman’s childhood, in which anyone who went to an all-girls’ school might recognise their own little horny selves and fellow students, we see Shamman infatuated with her teacher, Miss Charan, and fantasise about the older woman, just as we see Shamman become the object of desire for other girls her age.  Randu Purushanmar Chumbikkumbol (2017) by Kishor Kumar – MalayalamThis collection of Malayalam writing, whose title translates to “When Two Men Kiss”, spans the author’s personal experiences as well as a collection of essays on a range of subjects related to being queer.The personal portion of the book contains an autobiography – Kumar, an IIT graduate from Kerala, documents his life’s journey within India and abroad. We learn about his family, career, and his life as a gay man at various stages. The rest of the book is an assortment of interviews and Kumar’s essays exploring a range of topics including art and literature, politics, and psychology.

Randu Purushanmar Chumbikkumbol (2017) by Kishor Kumar – MalayalamThis collection of Malayalam writing, whose title translates to “When Two Men Kiss”, spans the author’s personal experiences as well as a collection of essays on a range of subjects related to being queer.The personal portion of the book contains an autobiography – Kumar, an IIT graduate from Kerala, documents his life’s journey within India and abroad. We learn about his family, career, and his life as a gay man at various stages. The rest of the book is an assortment of interviews and Kumar’s essays exploring a range of topics including art and literature, politics, and psychology. Untitled story (1968) by Bhupen Khakhar – GujaratiMohanlal is a middle-aged, reticent man, with a wife named Manjari and two children. When the story begins, we think it’s a story about Manjari and her relationship with her childhood flame Ratilal. But it’s also about Mohanlal’s gay relationship with a peon. This story was first published in the 1960s in a magazine called Kriti.Khakhar was better known for his paintings than for his writing, and according to Timothy Hyman, was “celebrated for his startling, visionary images of homosexual love”. Khakhar, who lived from 1934 to 2003, was open about being gay, and about the homoerotic themes in his work. Want more? Follow these online spaces to learn about new writing in regional languages: Xukia, Gaylaxy, Queer Ink, and Queer Chennai Chronicles.

Untitled story (1968) by Bhupen Khakhar – GujaratiMohanlal is a middle-aged, reticent man, with a wife named Manjari and two children. When the story begins, we think it’s a story about Manjari and her relationship with her childhood flame Ratilal. But it’s also about Mohanlal’s gay relationship with a peon. This story was first published in the 1960s in a magazine called Kriti.Khakhar was better known for his paintings than for his writing, and according to Timothy Hyman, was “celebrated for his startling, visionary images of homosexual love”. Khakhar, who lived from 1934 to 2003, was open about being gay, and about the homoerotic themes in his work. Want more? Follow these online spaces to learn about new writing in regional languages: Xukia, Gaylaxy, Queer Ink, and Queer Chennai Chronicles.