My Mom ran the unforgiving blades of scissors through my grandmother’s hair. Locks of hair floated to the ground. Ammuma’s expression was nonchalant.

Parkinsonism had taken over my grandmother’s health and she was finding it increasingly difficult to take care of herself; a lifetime spent taking care of those around her coming full circle. It was decided that the first order of business after the diagnosis was to get her hair cut to manageable proportions, an attempt at a fashionable 20s flapper bob on her spring curls.

Watching her hair being cut, I remembered her elaborate yet simple hair care routine. It was almost an unspoken and unwritten ritual. And, it never ceased to pique my childish curiosity in the many summer vacations we spent at my grandparents’ place in Kottayam.

Ammuma made her own concoction with copious amounts of coconut oil with sauteed onions and squashed hibiscus leaves from the yard. She would run her fingers vigorously through her charcoal-black curls, massage her roots, and douse her hair with this concoction. She did this before her bath every morning, humming a broken tune all along. And, she was committed to this ritual without leave.

As she stared aimlessly into the air while vast amounts of her precious hair were chopped off, I wondered how that woman from my memories would react to the scene unfolding before me.

Ammuma’s hair had a life of its own. It has been the dutiful confidante for all her secrets. Her only constant that bore witness to every passing moment in her life of over seventy years. Ammuma had never cut her hair, but her hair fell of its own accord as if the secrets got too heavy for it to hold.

As she grew older, her voluminous curls started to shed more profusely. She worried about bequeathing pathological hair-fall genes to her daughters. So, she would ritualistically apply another concoction of bhringaraj leaves on their hair as a preemptive measure. These recipes now exist in my mother’s recollections, a tacit heirloom that must have traversed centuries within the women of this family.

Ammuma does not talk much about glorious triumphs or lived experiences that usually comes with age. She had a diffident and calm demeanor that would always be an obstacle to her getting her way in things. She strove to not be the least wanted person in any room she was in. She led a life expended in servitude, from the only girl child in her family, to her marriage, to motherhood, and later grandmotherhood, before the onset of this disease, and she did it all with only the veins in the back of her hands to show for it.

Maybe it is my self-indulgence that makes me believe she stole away moments from her day for herself, moments where it was just her and her hair in a clandestine friendship, a bond shared by them in isolation, in their own little spiritual world filled with scented oils and scalp massages.

To trace my grandmother back to the woman she was before she became my Ammuma is inconceivable to me. She was not from an era that would lend itself to pictures either. There is a solitary black and white photograph of her: a tall figure in a floral sari, her hair loosely pulled back. I don’t ever remember seeing her stand as tall.

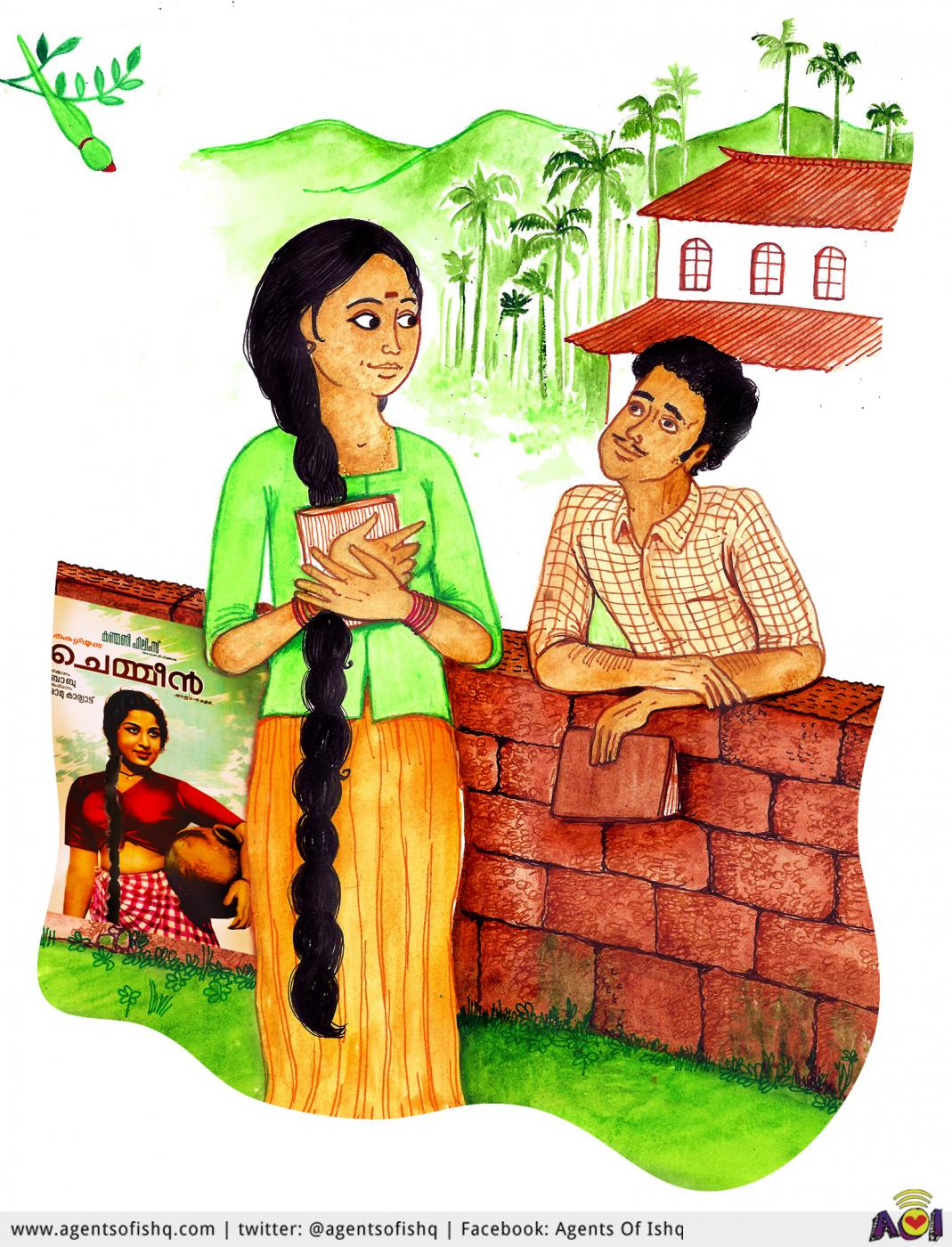

Ammuma is from an era where it was considered that the longer your plait grew, the more your charm would be. It was this same charm that enamored my grandfather. Ammuma was often compared to the actress Sheela, but in my Mom’s opinion Ammuma stood in her own league.

My Mom would talk of how Ammuma’s long luscious curls were her biggest asset. Even over the years of increasing personal neglect, Ammuma oiled and washed her hair every morning without break. I think it is the beauty of Ammuma’s hair and her relationship with her hair that makes for a fascinating story of this otherwise demure woman.

If her hair was one to divulge, it would talk about how she engaged in her own sorcery with food in her sanctum of a kitchen, how she took pleasure in playing cards so much so that she taught her grandchildren all the tactics of rummy, and how skillful she was when it came to needles and threads and the old timey sewing machine rusting away in the attic of my mother’s home. Her hair would harp about how a little schoolgirl used to tie it into pigtails with matching ribbons every morning as she made her way to her convent school, how her grandmother used to comb her all the clots of her thick curls back then. And, just like my mother does frequently, it would recite the story of my grandfather waiting outside my grandmother’s college to catch sight of her in a davani sari with her hair braided long when he was courting her. It would say all those things that people rarely ever talked about her, like how she sang along to that one folk song whenever it came on the radio, how she is a closeted chocolate aficionado who loves Cadbury’s and how she used to dedicatedly enjoy the novel spreads in the weekly lifestyle magazines. Her hair would applaud her for doing the best job at raising two generations, for holding our family together in a way no one else did, and it would do so proudly, for having been on that journey with her.

If my grandmother’s hair could talk, it would have also begged to not get cut.

Now as each tuft of hair fell against the air, victims one after the other of the sharp blades, I saw in them the lore of a life lived, never to be heard by another. It is not a look of helplessness that clouded my grandmother now, but one of resignation. I could not unsee the unfairness of this whole act. It is cruel and ungrateful of the universe to demand her hair - something that is so divine to my kind and selfless Ammuma.

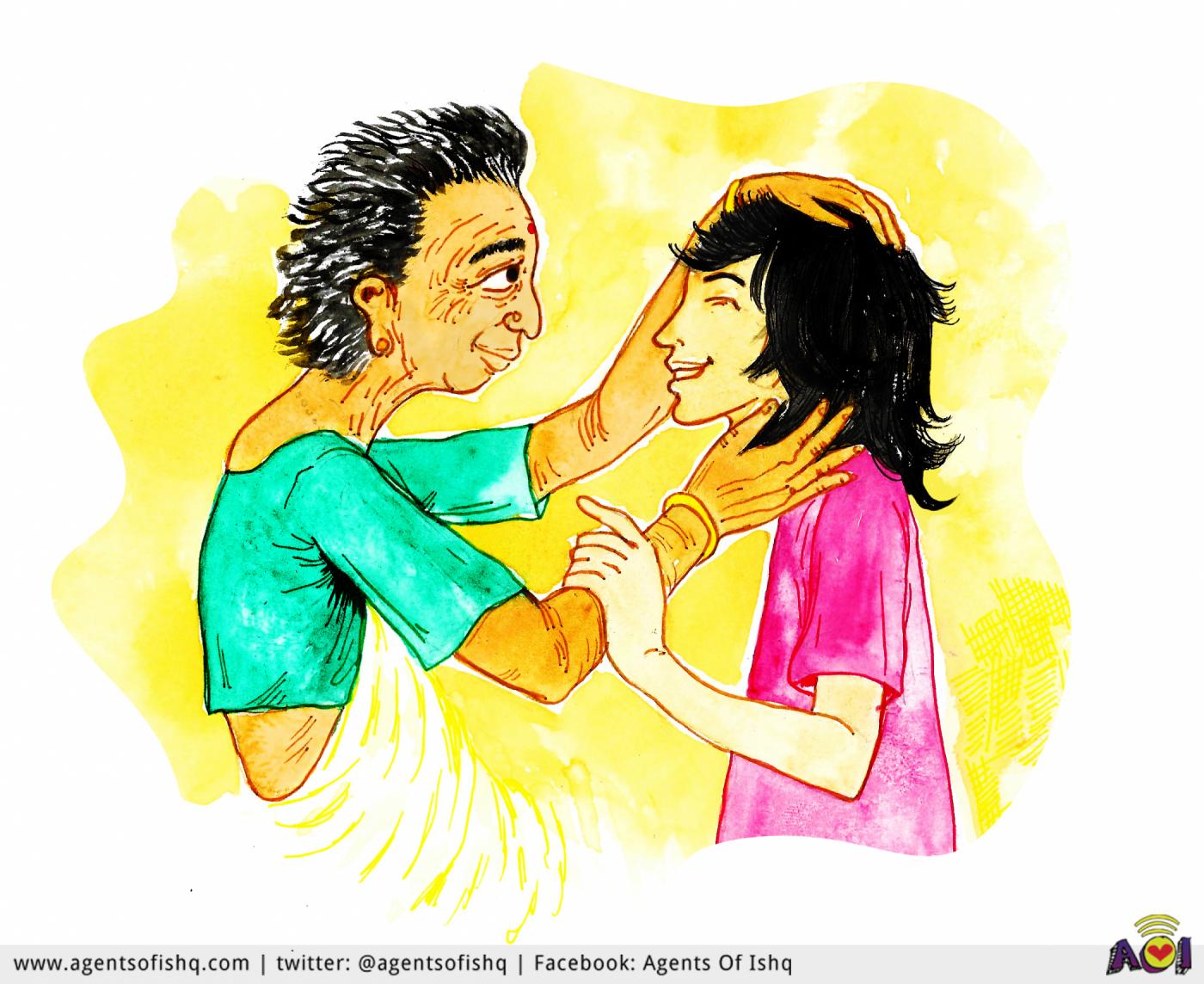

I don’t get to see her often now, as I live in Delhi far-away from the comfort of the weather and food at home. Returning home after six months, where I grew out my hair for a new look, I was met with all sorts of welcomes: comments on how much weight I had lost, enquiries about the flight journey, and even remarks on the political climate over there now.

My grandmother, however, held my hands, pulled me close, put both of her palms over my head and felt through my hair with a wide grin all along. I marveled at how a five-year old me could never have pictured having longer hair than Ammuma one day.

Hari is in an on again off again relationship with writing, whilst juggling his bachelor's studies in social sciences. When he's not busy on his quest to visit every monument in Delhi, you can find him obsessing over old Hollywood and rajma chawal.