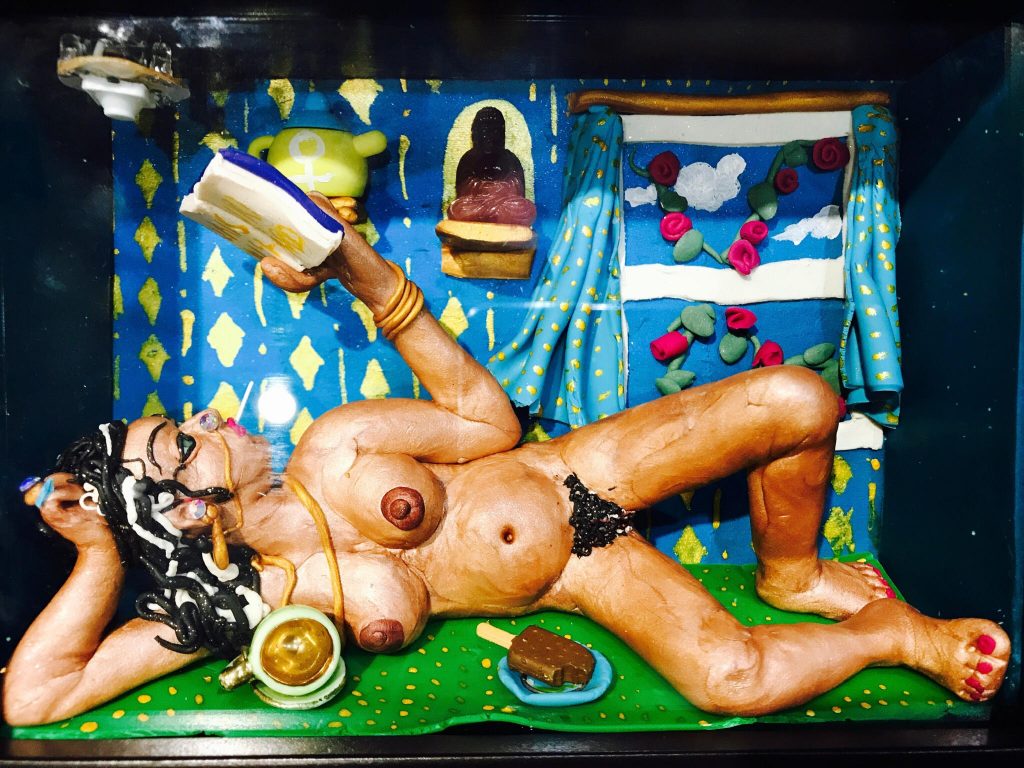

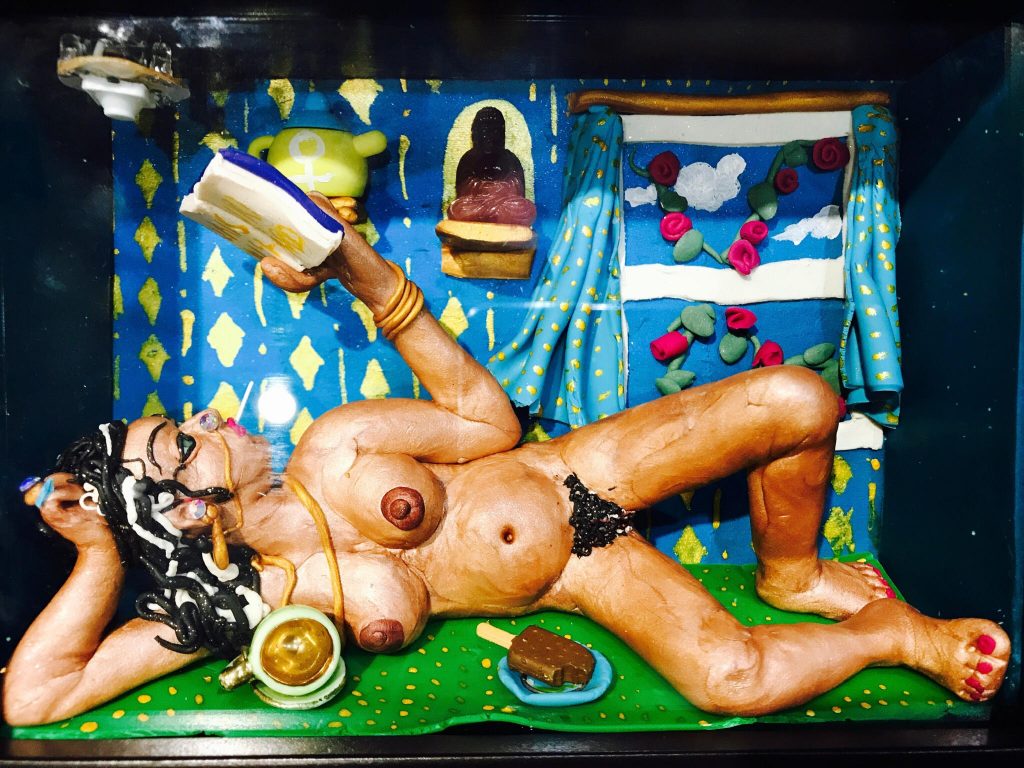

Love is pretty much the governing force of why I make what I do. In the (Western) contemporary art world, love is almost this taboo thing that we’re never meant to talk about. But at the end of the day, it is really what drives us to be in, create, and engage with the world in the way that we do. I explore my love of every thing that is, in a way, deemed the ‘other’, both by Hindutva or the BJP as well as Republican white supremacists (since I live in the US). So if they’re putting out a lot of hate in the world, I can try to put out a lot of love out into the world, towards the very people that they are hating – my queer friends, trans friends, Dalit and Muslim friends, feminists who are doing work that is in direct opposition to right wing fundamentalists. What I can do with my work is create things that counter that hate within my practice. Both as a maker and a consumer, the works that I respond to are the works that have a really big emotional impact on me, and so, when I’m making work, I try very much to think about what emotions that I’m feeling, whether it’s rage or love or lust, or whatever it may be, and I try to make sure that my work does communicate that (whether it’s through painting, or sculpture, or my curatorial work). Here are six of my works that mean a lot to me in that sense. Mum’s holiday, 2017I made this one while my child was away! It has a woman alone, enjoying the pleasure of solitude, and the freedom of solitude. There’s an open window and curtains fluttering in the breeze, and here she is, reading her book, eating her ice cream, having her joint. The figure of the woman itself is based on those little metal reading ladies from back in the 90s that were crafted by folk artists in India, like the lady lying down on a charpai with a book in her hand made of coiled metal. What I love so much about those reading ladies is how they represent pleasure and erotica and information and knowledge about one’s own body and sexuality and sensuality. To me this piece really speaks to that, the way she’s with her legs wide open and the breeze is going…wherever it needs to go! It has that element of being shameless, and on your own, and uninhibited and at ease with your body and with the pleasures that your body gives you.

Mum’s holiday, 2017I made this one while my child was away! It has a woman alone, enjoying the pleasure of solitude, and the freedom of solitude. There’s an open window and curtains fluttering in the breeze, and here she is, reading her book, eating her ice cream, having her joint. The figure of the woman itself is based on those little metal reading ladies from back in the 90s that were crafted by folk artists in India, like the lady lying down on a charpai with a book in her hand made of coiled metal. What I love so much about those reading ladies is how they represent pleasure and erotica and information and knowledge about one’s own body and sexuality and sensuality. To me this piece really speaks to that, the way she’s with her legs wide open and the breeze is going…wherever it needs to go! It has that element of being shameless, and on your own, and uninhibited and at ease with your body and with the pleasures that your body gives you. Holy family (left) and Swag (right), 2017Holy family was made because I’m always in love with watching all of my lesbian girlfriends who’ve gotten married and have kids together, and I get to see what intimacy and motherhood can look like without patriarchy being attached to it. I thought it was really important to reinvent the holy family, especially as it pertains to Hinduism in this specific way. I guess in a way I lost my faith and I’m trying to find it through my work.I thought instead of the usual Rama-Sita, Vishnu-Lakshmi and Krishna-Radha, we’ll have these two. And I thought it was important to have the intimacy between these two figures, they’re very close to a kiss, but then they also have their children in their arms, so there is love and sensuality and motherhood all perfectly intertwined. The idea of the child that has the lotus head is because so many of my friends have chosen not to have children and their life’s work is, to me, their child. It’s what they nurture and grow. The other sculpture in the picture is my homage to Kiran Gandhi, who ran the London marathon when she had her period and decided to freebleed. I was super inspired by her, and I called it Swag, just for the sheer self confidence she had to do that and give so many women joy around the world. That was fucking badass!I make the kind of goddesses that I want to see. I have had a very long and deep engagement with Hinduism before rejecting it, and the reality is that I’m constantly frustrated by the fact that temples – in America, at least – don’t have women priests. We can never, ever get to the inner sanctum – we always have males mediating between us and the gods. And what’s happening in Kerala infuriates me to the point where I feel absolutely compelled to make these deities for ourselves. It’s really my rage at religion that compels me over and over and over to make this vision of feminine … witchery, I guess (the writer Kavita Das called my work “sculptural manifestos to feminist witchery”, and I really love that), because I’ve had it with religious fundamentalism of all types. I’m on a mission to make as many fierce, naked, subversive, in-their-face goddesses as I possibly can.

Holy family (left) and Swag (right), 2017Holy family was made because I’m always in love with watching all of my lesbian girlfriends who’ve gotten married and have kids together, and I get to see what intimacy and motherhood can look like without patriarchy being attached to it. I thought it was really important to reinvent the holy family, especially as it pertains to Hinduism in this specific way. I guess in a way I lost my faith and I’m trying to find it through my work.I thought instead of the usual Rama-Sita, Vishnu-Lakshmi and Krishna-Radha, we’ll have these two. And I thought it was important to have the intimacy between these two figures, they’re very close to a kiss, but then they also have their children in their arms, so there is love and sensuality and motherhood all perfectly intertwined. The idea of the child that has the lotus head is because so many of my friends have chosen not to have children and their life’s work is, to me, their child. It’s what they nurture and grow. The other sculpture in the picture is my homage to Kiran Gandhi, who ran the London marathon when she had her period and decided to freebleed. I was super inspired by her, and I called it Swag, just for the sheer self confidence she had to do that and give so many women joy around the world. That was fucking badass!I make the kind of goddesses that I want to see. I have had a very long and deep engagement with Hinduism before rejecting it, and the reality is that I’m constantly frustrated by the fact that temples – in America, at least – don’t have women priests. We can never, ever get to the inner sanctum – we always have males mediating between us and the gods. And what’s happening in Kerala infuriates me to the point where I feel absolutely compelled to make these deities for ourselves. It’s really my rage at religion that compels me over and over and over to make this vision of feminine … witchery, I guess (the writer Kavita Das called my work “sculptural manifestos to feminist witchery”, and I really love that), because I’ve had it with religious fundamentalism of all types. I’m on a mission to make as many fierce, naked, subversive, in-their-face goddesses as I possibly can. Two boys in saris, 2018They’re a couple, Muhammad Ali and Amar, who live in Australia, they’re just this delightful pair of Muslim queens. I’ve never met them. They’re just so fashion forward, and they have a food truck, and they perform, and they serve up all this deliciousness and I’m endlessly inspired by them and so I decided to make this sculpture of them. It was about loving, celebrating, privileging these queer brown Muslim boys, who are doing what they do. To me, queerness is both a lived experience and a philosophy. I see queerness as the freedom to love the people that you love regardless of their gender, in a non-heteronormative way. I don’t feel qualified to define it for anyone else, but in my own life, I’m what’s now called pansexual, which means that I love people for who they are. In the past I’ve had boyfriends and girlfriends, and I may be married to a man now, but it doesn’t change who I have loved and been with, or who I have been in community with for a long time. I now live with the privilege of a cisgendered married woman, but my whole life I have been surrounded by queerness, and I am queer, and its part of my work and that’s really important to me.

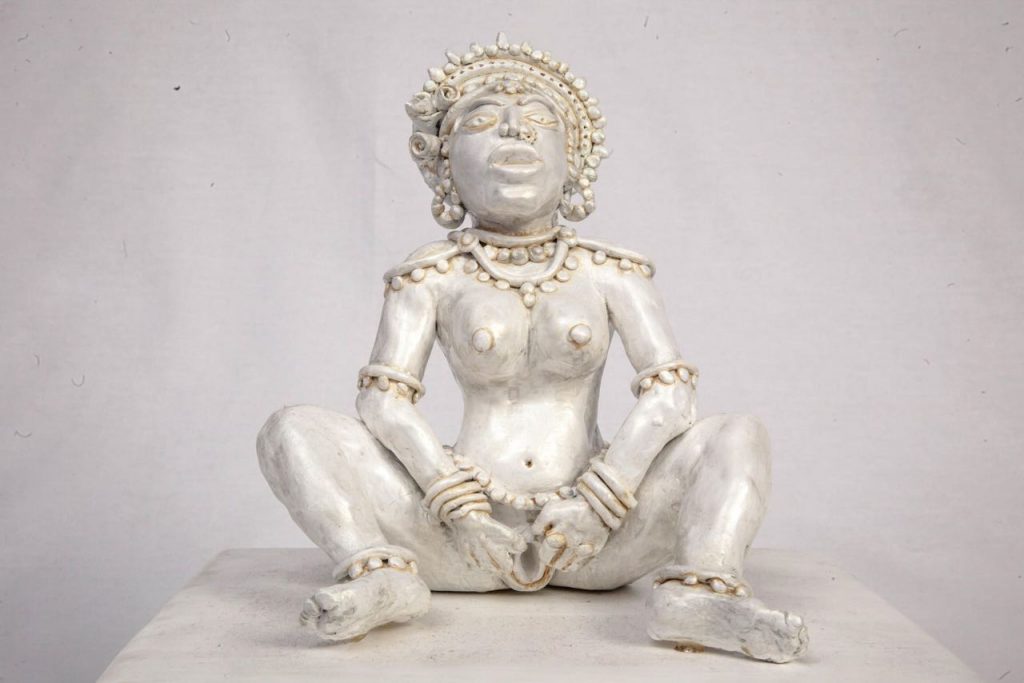

Two boys in saris, 2018They’re a couple, Muhammad Ali and Amar, who live in Australia, they’re just this delightful pair of Muslim queens. I’ve never met them. They’re just so fashion forward, and they have a food truck, and they perform, and they serve up all this deliciousness and I’m endlessly inspired by them and so I decided to make this sculpture of them. It was about loving, celebrating, privileging these queer brown Muslim boys, who are doing what they do. To me, queerness is both a lived experience and a philosophy. I see queerness as the freedom to love the people that you love regardless of their gender, in a non-heteronormative way. I don’t feel qualified to define it for anyone else, but in my own life, I’m what’s now called pansexual, which means that I love people for who they are. In the past I’ve had boyfriends and girlfriends, and I may be married to a man now, but it doesn’t change who I have loved and been with, or who I have been in community with for a long time. I now live with the privilege of a cisgendered married woman, but my whole life I have been surrounded by queerness, and I am queer, and its part of my work and that’s really important to me. Before Kali 107 (extreme left), 2015The idea in this sculpture is really to try and find that visual pleasure that I look for myself. I don’t really find much porn interesting – I find most of it to be boring, and creepy, and disgusting, and find it hard to be turned on by it. But my fantasies are pretty much always queer. And even when you look for women in porn, you find things that are basically made for the male gaze, not for the female gaze at all. This sculpture is based on a scene from a Pedro Almodovar film, between a woman and a drag queen which I found to be extremely erotic and beautiful and sexy. That made me think more about what women’s pleasure would look like without men, so I thought of having a column of endless female pleasure.This sculpture was done as part of my ‘Before Kali’ series, which is based on Indus Valley artefacts. It’s really important for me to represent bodies that are not traditionally represented in Indian sculpture anymore. In classical forms of Indian sculpture, things have been very codified and rigid for centuries, and to make a certain deity you have to follow a very prescribed set of measurements and proportions and signifiers. What I love so much about those Indus Valley artefacts is that they predated the Vedas and Sutras and prescriptions for what a woman’s body should look like, and they had this incredible plethora of diversity from one-breasted to almost-male to fat to thin to old to shriveled. That style of sculpture represented bodies as they are, and it is no longer so. And so for me to represent the type of body that I have – this sagging, overweight, middle-aged body – became necessary. There’s a way in which I, as a woman, have to teach myself to love myself through making this work and allowing everybody to love these bodies. It’s as much for me as it is for other women I know whose bodies have done similar things. I’m not interested in traditional representations of femininity, and I want my women to have the arms that grew on my body from lifting my child and wrestling with my materials and the belly that never went away from my child growing in it.

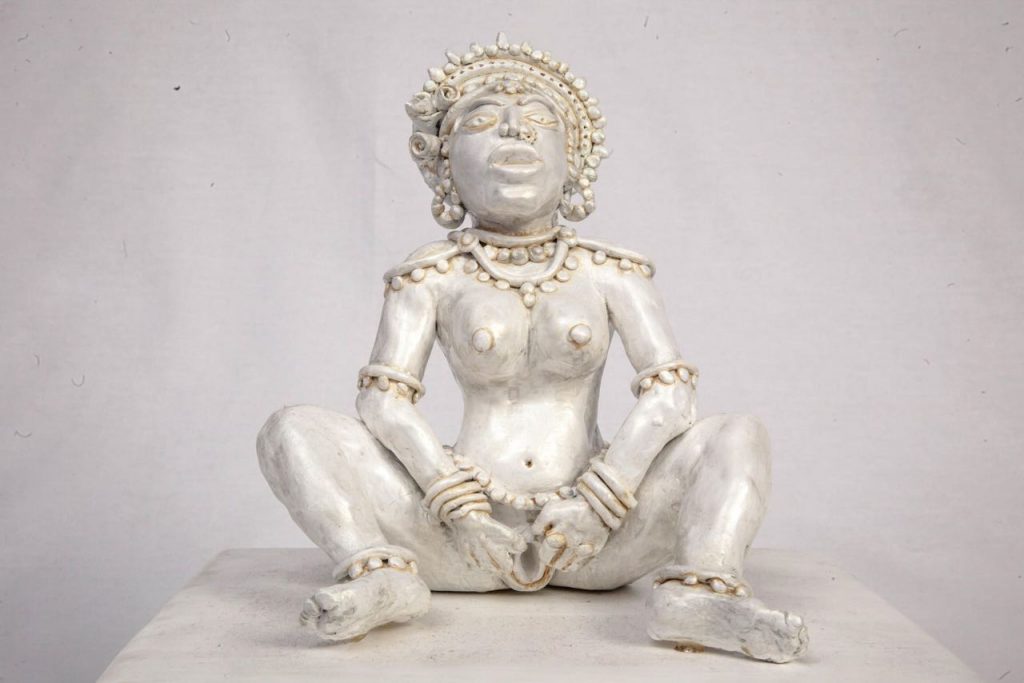

Before Kali 107 (extreme left), 2015The idea in this sculpture is really to try and find that visual pleasure that I look for myself. I don’t really find much porn interesting – I find most of it to be boring, and creepy, and disgusting, and find it hard to be turned on by it. But my fantasies are pretty much always queer. And even when you look for women in porn, you find things that are basically made for the male gaze, not for the female gaze at all. This sculpture is based on a scene from a Pedro Almodovar film, between a woman and a drag queen which I found to be extremely erotic and beautiful and sexy. That made me think more about what women’s pleasure would look like without men, so I thought of having a column of endless female pleasure.This sculpture was done as part of my ‘Before Kali’ series, which is based on Indus Valley artefacts. It’s really important for me to represent bodies that are not traditionally represented in Indian sculpture anymore. In classical forms of Indian sculpture, things have been very codified and rigid for centuries, and to make a certain deity you have to follow a very prescribed set of measurements and proportions and signifiers. What I love so much about those Indus Valley artefacts is that they predated the Vedas and Sutras and prescriptions for what a woman’s body should look like, and they had this incredible plethora of diversity from one-breasted to almost-male to fat to thin to old to shriveled. That style of sculpture represented bodies as they are, and it is no longer so. And so for me to represent the type of body that I have – this sagging, overweight, middle-aged body – became necessary. There’s a way in which I, as a woman, have to teach myself to love myself through making this work and allowing everybody to love these bodies. It’s as much for me as it is for other women I know whose bodies have done similar things. I’m not interested in traditional representations of femininity, and I want my women to have the arms that grew on my body from lifting my child and wrestling with my materials and the belly that never went away from my child growing in it.  Before Kali, 2018This was my last sculpture in the ‘Before Kali’ series, for which I wanted to do a kind of lajja-gauri-meets-sheela-na-gig. Lajja gauri is a form in which the goddess is lotus-headed, and she has her legs splayed wide open with her vulva entirely exposed. It’s a really old form and it’s used in India, Nepal, and several other countries all over the world. In European countries it’s this old hag opening up her giant vagina – in Ireland it’s called Sheela na gig. They’re both related female goddess figures – mother goddess archetypes. I think when I first saw that form I was a little taken aback myself by how bold it is, and it took me time to process this pose of such openness, this complete surrender that’s also an invitation. Right now, I think the world is really, really confused about love and sex in so many ways. You had feminists from the West (where I live) who said they were having a sexual revolution and liberating women. Certainly some women were allowed the privilege of owning their sexualities, but the reality is that it gave patriarchy a new script for how to control women’s bodies, and made women more available to men. And so men continued to be their abusive selves, and women have now come to a place where we recognise how deeply harmful this way of being is and we’re looking to find healthier ways of being. I think there has to be a reconfiguration of what all this means. The truth is that not everybody has a horrendous dysfunctional relationship or sexual experience, and I know from personal experience that it is possible to move on from trauma towards a wonderful sexual and emotional intimacy. People have to be taught to speak about consent and pleasure – can we please move beyond the pain to actually, like, how can we do this well? I think art is the perfect place for that: it allows people permission to look at and feel things that they may not necessarily give themselves the space to think about – like autonomy, pleasure, and joy. Jaishri Abichandani was born in Mumbai in 1969 and received her MFA from Goldsmith’s College, University of London. She is organising a trilogy of inaugural exhibitions for the Ford Foundation Gallery .

Before Kali, 2018This was my last sculpture in the ‘Before Kali’ series, for which I wanted to do a kind of lajja-gauri-meets-sheela-na-gig. Lajja gauri is a form in which the goddess is lotus-headed, and she has her legs splayed wide open with her vulva entirely exposed. It’s a really old form and it’s used in India, Nepal, and several other countries all over the world. In European countries it’s this old hag opening up her giant vagina – in Ireland it’s called Sheela na gig. They’re both related female goddess figures – mother goddess archetypes. I think when I first saw that form I was a little taken aback myself by how bold it is, and it took me time to process this pose of such openness, this complete surrender that’s also an invitation. Right now, I think the world is really, really confused about love and sex in so many ways. You had feminists from the West (where I live) who said they were having a sexual revolution and liberating women. Certainly some women were allowed the privilege of owning their sexualities, but the reality is that it gave patriarchy a new script for how to control women’s bodies, and made women more available to men. And so men continued to be their abusive selves, and women have now come to a place where we recognise how deeply harmful this way of being is and we’re looking to find healthier ways of being. I think there has to be a reconfiguration of what all this means. The truth is that not everybody has a horrendous dysfunctional relationship or sexual experience, and I know from personal experience that it is possible to move on from trauma towards a wonderful sexual and emotional intimacy. People have to be taught to speak about consent and pleasure – can we please move beyond the pain to actually, like, how can we do this well? I think art is the perfect place for that: it allows people permission to look at and feel things that they may not necessarily give themselves the space to think about – like autonomy, pleasure, and joy. Jaishri Abichandani was born in Mumbai in 1969 and received her MFA from Goldsmith’s College, University of London. She is organising a trilogy of inaugural exhibitions for the Ford Foundation Gallery .

Mum’s holiday, 2017I made this one while my child was away! It has a woman alone, enjoying the pleasure of solitude, and the freedom of solitude. There’s an open window and curtains fluttering in the breeze, and here she is, reading her book, eating her ice cream, having her joint. The figure of the woman itself is based on those little metal reading ladies from back in the 90s that were crafted by folk artists in India, like the lady lying down on a charpai with a book in her hand made of coiled metal. What I love so much about those reading ladies is how they represent pleasure and erotica and information and knowledge about one’s own body and sexuality and sensuality. To me this piece really speaks to that, the way she’s with her legs wide open and the breeze is going…wherever it needs to go! It has that element of being shameless, and on your own, and uninhibited and at ease with your body and with the pleasures that your body gives you.

Mum’s holiday, 2017I made this one while my child was away! It has a woman alone, enjoying the pleasure of solitude, and the freedom of solitude. There’s an open window and curtains fluttering in the breeze, and here she is, reading her book, eating her ice cream, having her joint. The figure of the woman itself is based on those little metal reading ladies from back in the 90s that were crafted by folk artists in India, like the lady lying down on a charpai with a book in her hand made of coiled metal. What I love so much about those reading ladies is how they represent pleasure and erotica and information and knowledge about one’s own body and sexuality and sensuality. To me this piece really speaks to that, the way she’s with her legs wide open and the breeze is going…wherever it needs to go! It has that element of being shameless, and on your own, and uninhibited and at ease with your body and with the pleasures that your body gives you. Holy family (left) and Swag (right), 2017Holy family was made because I’m always in love with watching all of my lesbian girlfriends who’ve gotten married and have kids together, and I get to see what intimacy and motherhood can look like without patriarchy being attached to it. I thought it was really important to reinvent the holy family, especially as it pertains to Hinduism in this specific way. I guess in a way I lost my faith and I’m trying to find it through my work.I thought instead of the usual Rama-Sita, Vishnu-Lakshmi and Krishna-Radha, we’ll have these two. And I thought it was important to have the intimacy between these two figures, they’re very close to a kiss, but then they also have their children in their arms, so there is love and sensuality and motherhood all perfectly intertwined. The idea of the child that has the lotus head is because so many of my friends have chosen not to have children and their life’s work is, to me, their child. It’s what they nurture and grow. The other sculpture in the picture is my homage to Kiran Gandhi, who ran the London marathon when she had her period and decided to freebleed. I was super inspired by her, and I called it Swag, just for the sheer self confidence she had to do that and give so many women joy around the world. That was fucking badass!I make the kind of goddesses that I want to see. I have had a very long and deep engagement with Hinduism before rejecting it, and the reality is that I’m constantly frustrated by the fact that temples – in America, at least – don’t have women priests. We can never, ever get to the inner sanctum – we always have males mediating between us and the gods. And what’s happening in Kerala infuriates me to the point where I feel absolutely compelled to make these deities for ourselves. It’s really my rage at religion that compels me over and over and over to make this vision of feminine … witchery, I guess (the writer Kavita Das called my work “sculptural manifestos to feminist witchery”, and I really love that), because I’ve had it with religious fundamentalism of all types. I’m on a mission to make as many fierce, naked, subversive, in-their-face goddesses as I possibly can.

Holy family (left) and Swag (right), 2017Holy family was made because I’m always in love with watching all of my lesbian girlfriends who’ve gotten married and have kids together, and I get to see what intimacy and motherhood can look like without patriarchy being attached to it. I thought it was really important to reinvent the holy family, especially as it pertains to Hinduism in this specific way. I guess in a way I lost my faith and I’m trying to find it through my work.I thought instead of the usual Rama-Sita, Vishnu-Lakshmi and Krishna-Radha, we’ll have these two. And I thought it was important to have the intimacy between these two figures, they’re very close to a kiss, but then they also have their children in their arms, so there is love and sensuality and motherhood all perfectly intertwined. The idea of the child that has the lotus head is because so many of my friends have chosen not to have children and their life’s work is, to me, their child. It’s what they nurture and grow. The other sculpture in the picture is my homage to Kiran Gandhi, who ran the London marathon when she had her period and decided to freebleed. I was super inspired by her, and I called it Swag, just for the sheer self confidence she had to do that and give so many women joy around the world. That was fucking badass!I make the kind of goddesses that I want to see. I have had a very long and deep engagement with Hinduism before rejecting it, and the reality is that I’m constantly frustrated by the fact that temples – in America, at least – don’t have women priests. We can never, ever get to the inner sanctum – we always have males mediating between us and the gods. And what’s happening in Kerala infuriates me to the point where I feel absolutely compelled to make these deities for ourselves. It’s really my rage at religion that compels me over and over and over to make this vision of feminine … witchery, I guess (the writer Kavita Das called my work “sculptural manifestos to feminist witchery”, and I really love that), because I’ve had it with religious fundamentalism of all types. I’m on a mission to make as many fierce, naked, subversive, in-their-face goddesses as I possibly can. Two boys in saris, 2018They’re a couple, Muhammad Ali and Amar, who live in Australia, they’re just this delightful pair of Muslim queens. I’ve never met them. They’re just so fashion forward, and they have a food truck, and they perform, and they serve up all this deliciousness and I’m endlessly inspired by them and so I decided to make this sculpture of them. It was about loving, celebrating, privileging these queer brown Muslim boys, who are doing what they do. To me, queerness is both a lived experience and a philosophy. I see queerness as the freedom to love the people that you love regardless of their gender, in a non-heteronormative way. I don’t feel qualified to define it for anyone else, but in my own life, I’m what’s now called pansexual, which means that I love people for who they are. In the past I’ve had boyfriends and girlfriends, and I may be married to a man now, but it doesn’t change who I have loved and been with, or who I have been in community with for a long time. I now live with the privilege of a cisgendered married woman, but my whole life I have been surrounded by queerness, and I am queer, and its part of my work and that’s really important to me.

Two boys in saris, 2018They’re a couple, Muhammad Ali and Amar, who live in Australia, they’re just this delightful pair of Muslim queens. I’ve never met them. They’re just so fashion forward, and they have a food truck, and they perform, and they serve up all this deliciousness and I’m endlessly inspired by them and so I decided to make this sculpture of them. It was about loving, celebrating, privileging these queer brown Muslim boys, who are doing what they do. To me, queerness is both a lived experience and a philosophy. I see queerness as the freedom to love the people that you love regardless of their gender, in a non-heteronormative way. I don’t feel qualified to define it for anyone else, but in my own life, I’m what’s now called pansexual, which means that I love people for who they are. In the past I’ve had boyfriends and girlfriends, and I may be married to a man now, but it doesn’t change who I have loved and been with, or who I have been in community with for a long time. I now live with the privilege of a cisgendered married woman, but my whole life I have been surrounded by queerness, and I am queer, and its part of my work and that’s really important to me. Before Kali 107 (extreme left), 2015The idea in this sculpture is really to try and find that visual pleasure that I look for myself. I don’t really find much porn interesting – I find most of it to be boring, and creepy, and disgusting, and find it hard to be turned on by it. But my fantasies are pretty much always queer. And even when you look for women in porn, you find things that are basically made for the male gaze, not for the female gaze at all. This sculpture is based on a scene from a Pedro Almodovar film, between a woman and a drag queen which I found to be extremely erotic and beautiful and sexy. That made me think more about what women’s pleasure would look like without men, so I thought of having a column of endless female pleasure.This sculpture was done as part of my ‘Before Kali’ series, which is based on Indus Valley artefacts. It’s really important for me to represent bodies that are not traditionally represented in Indian sculpture anymore. In classical forms of Indian sculpture, things have been very codified and rigid for centuries, and to make a certain deity you have to follow a very prescribed set of measurements and proportions and signifiers. What I love so much about those Indus Valley artefacts is that they predated the Vedas and Sutras and prescriptions for what a woman’s body should look like, and they had this incredible plethora of diversity from one-breasted to almost-male to fat to thin to old to shriveled. That style of sculpture represented bodies as they are, and it is no longer so. And so for me to represent the type of body that I have – this sagging, overweight, middle-aged body – became necessary. There’s a way in which I, as a woman, have to teach myself to love myself through making this work and allowing everybody to love these bodies. It’s as much for me as it is for other women I know whose bodies have done similar things. I’m not interested in traditional representations of femininity, and I want my women to have the arms that grew on my body from lifting my child and wrestling with my materials and the belly that never went away from my child growing in it.

Before Kali 107 (extreme left), 2015The idea in this sculpture is really to try and find that visual pleasure that I look for myself. I don’t really find much porn interesting – I find most of it to be boring, and creepy, and disgusting, and find it hard to be turned on by it. But my fantasies are pretty much always queer. And even when you look for women in porn, you find things that are basically made for the male gaze, not for the female gaze at all. This sculpture is based on a scene from a Pedro Almodovar film, between a woman and a drag queen which I found to be extremely erotic and beautiful and sexy. That made me think more about what women’s pleasure would look like without men, so I thought of having a column of endless female pleasure.This sculpture was done as part of my ‘Before Kali’ series, which is based on Indus Valley artefacts. It’s really important for me to represent bodies that are not traditionally represented in Indian sculpture anymore. In classical forms of Indian sculpture, things have been very codified and rigid for centuries, and to make a certain deity you have to follow a very prescribed set of measurements and proportions and signifiers. What I love so much about those Indus Valley artefacts is that they predated the Vedas and Sutras and prescriptions for what a woman’s body should look like, and they had this incredible plethora of diversity from one-breasted to almost-male to fat to thin to old to shriveled. That style of sculpture represented bodies as they are, and it is no longer so. And so for me to represent the type of body that I have – this sagging, overweight, middle-aged body – became necessary. There’s a way in which I, as a woman, have to teach myself to love myself through making this work and allowing everybody to love these bodies. It’s as much for me as it is for other women I know whose bodies have done similar things. I’m not interested in traditional representations of femininity, and I want my women to have the arms that grew on my body from lifting my child and wrestling with my materials and the belly that never went away from my child growing in it.  Before Kali, 2018This was my last sculpture in the ‘Before Kali’ series, for which I wanted to do a kind of lajja-gauri-meets-sheela-na-gig. Lajja gauri is a form in which the goddess is lotus-headed, and she has her legs splayed wide open with her vulva entirely exposed. It’s a really old form and it’s used in India, Nepal, and several other countries all over the world. In European countries it’s this old hag opening up her giant vagina – in Ireland it’s called Sheela na gig. They’re both related female goddess figures – mother goddess archetypes. I think when I first saw that form I was a little taken aback myself by how bold it is, and it took me time to process this pose of such openness, this complete surrender that’s also an invitation. Right now, I think the world is really, really confused about love and sex in so many ways. You had feminists from the West (where I live) who said they were having a sexual revolution and liberating women. Certainly some women were allowed the privilege of owning their sexualities, but the reality is that it gave patriarchy a new script for how to control women’s bodies, and made women more available to men. And so men continued to be their abusive selves, and women have now come to a place where we recognise how deeply harmful this way of being is and we’re looking to find healthier ways of being. I think there has to be a reconfiguration of what all this means. The truth is that not everybody has a horrendous dysfunctional relationship or sexual experience, and I know from personal experience that it is possible to move on from trauma towards a wonderful sexual and emotional intimacy. People have to be taught to speak about consent and pleasure – can we please move beyond the pain to actually, like, how can we do this well? I think art is the perfect place for that: it allows people permission to look at and feel things that they may not necessarily give themselves the space to think about – like autonomy, pleasure, and joy. Jaishri Abichandani was born in Mumbai in 1969 and received her MFA from Goldsmith’s College, University of London. She is organising a trilogy of inaugural exhibitions for the Ford Foundation Gallery .

Before Kali, 2018This was my last sculpture in the ‘Before Kali’ series, for which I wanted to do a kind of lajja-gauri-meets-sheela-na-gig. Lajja gauri is a form in which the goddess is lotus-headed, and she has her legs splayed wide open with her vulva entirely exposed. It’s a really old form and it’s used in India, Nepal, and several other countries all over the world. In European countries it’s this old hag opening up her giant vagina – in Ireland it’s called Sheela na gig. They’re both related female goddess figures – mother goddess archetypes. I think when I first saw that form I was a little taken aback myself by how bold it is, and it took me time to process this pose of such openness, this complete surrender that’s also an invitation. Right now, I think the world is really, really confused about love and sex in so many ways. You had feminists from the West (where I live) who said they were having a sexual revolution and liberating women. Certainly some women were allowed the privilege of owning their sexualities, but the reality is that it gave patriarchy a new script for how to control women’s bodies, and made women more available to men. And so men continued to be their abusive selves, and women have now come to a place where we recognise how deeply harmful this way of being is and we’re looking to find healthier ways of being. I think there has to be a reconfiguration of what all this means. The truth is that not everybody has a horrendous dysfunctional relationship or sexual experience, and I know from personal experience that it is possible to move on from trauma towards a wonderful sexual and emotional intimacy. People have to be taught to speak about consent and pleasure – can we please move beyond the pain to actually, like, how can we do this well? I think art is the perfect place for that: it allows people permission to look at and feel things that they may not necessarily give themselves the space to think about – like autonomy, pleasure, and joy. Jaishri Abichandani was born in Mumbai in 1969 and received her MFA from Goldsmith’s College, University of London. She is organising a trilogy of inaugural exhibitions for the Ford Foundation Gallery .