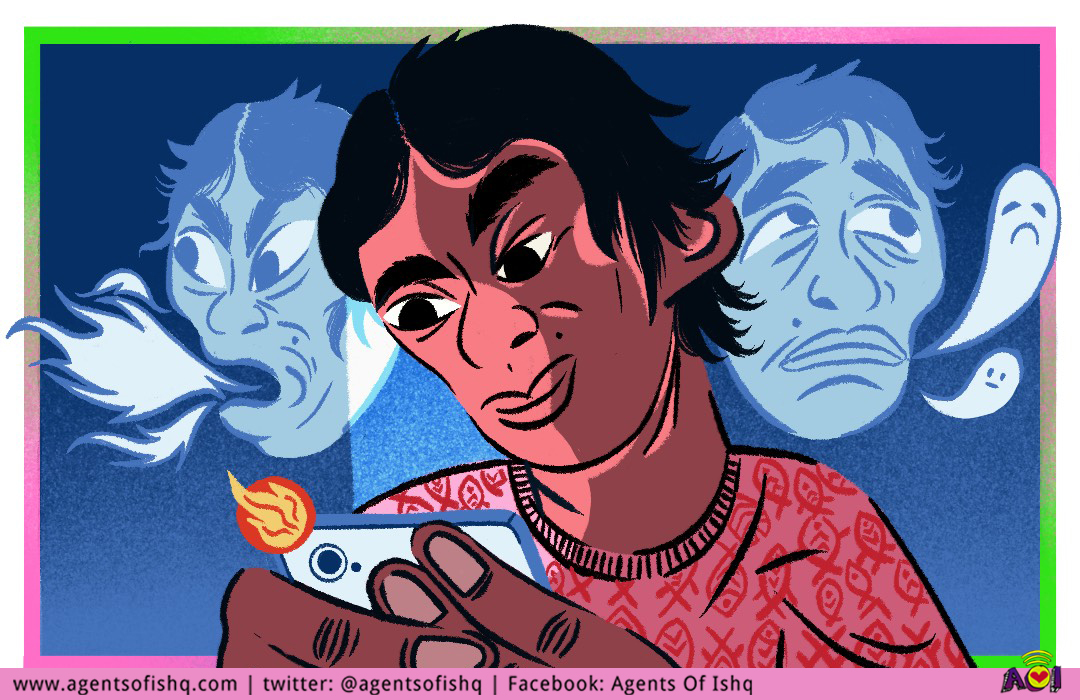

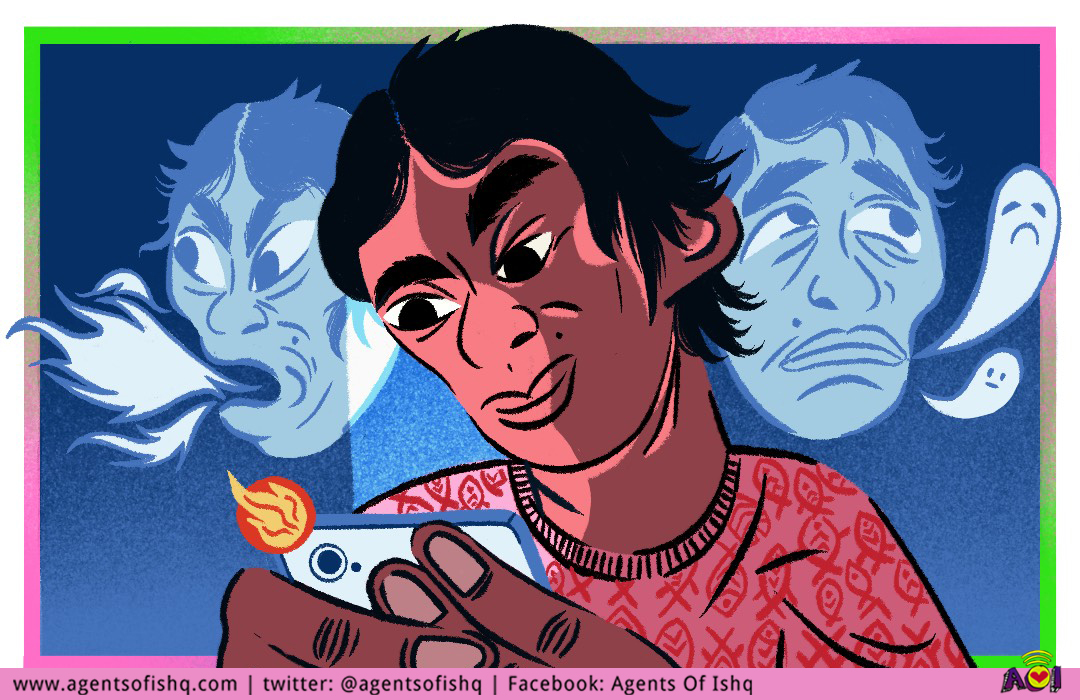

I recently received a message from one of my batch mates from school. Just an innocent “hello”, and a rather non-threatening “how have you been?” Not normally a message to make one sweat, but this scenario was different. No matter how innocent sounding the message, the voice of the person on the other end still rang clear and loud in my head, coloured with a sizeable litany of slurs and insults that had made fourteen-year-old me shiver and flush with embarrassment. The sender was none other than my old high school bully, and with his one hello, he had, just like that, managed to not only ruin my day, but also undo much of the healing and unlearning I had striven for in my adult life. I felt vulnerable, and my reflex was to be defensive.I did not respond to the message for weeks. I felt like I owed nothing to this spectre from the past who had brought me nothing but pain and trauma. The thought of engaging in conversation with him made my heart pound and the blood rush to my head in a poisonous mixture of shame and anger.I recall an incident where I was playing cricket during our school PT class. I was already a confused and uncoordinated kid, and my awkward gait and consistent inability to catch the ball properly had halted our game, much to the frustration of the other players. Ours was not a particularly progressive school, so naturally, this was a “girls team vs boys team” situation where the entire reputation of the boys’ team hinged on us winning the match. I vividly remember being in the centre of a large circle of boys who did not want me on their team, their jeering egged on by my bully who had declared me a “chakka” because of how hilariously girly I looked while running. I sat huddled in a heap on the ground, hot tears of embarrassment threatening to burst forth and confirm everyone’s suspicions. The term stuck, and I would spend the next six years of my life dreading every trip to the park for PT classes. I did not want to be in a space where I was once again vulnerable not only to the goading and the bullying, but also to the million other internalised societal biases around gender that came with being bullied in high school. That this person, who knew a version of me from the past that I no longer was, could disrupt my day and induce such panic so easily even after all these years, was scary and left me frustrated with my own inability to “move on” from the bullying. When I eventually responded to his message months after, I was surprised to received an instant reply. It was a long-ish message, full of buzz words like “accountability” and “self-improvement” that put my back up. To be honest, I still haven’t fully read it, and I’m not sure that I ever will. Regardless of the guilt that this person felt, I did not want the onus of his apology to fall on me. I did not want to assuage his guilt, I did not want to provide him with the comfort of “it’s okay, we were kids” (even though we were), and I certainly did not want to provide him with the closure of getting a proper reply from me. I won’t deny there was a vindictive, if petty, satisfaction leaving this person hanging. In fact, I turned my read notifications on specifically so that I could drive home the point that Yes, I have seen your little Paragraph, and I Don’t Care™. Let him wallow in his guilt for eternity, said I, in an imperious British accent in my head.In my school, much like in most other English medium schools in Mumbai, there was a very well established social hierarchy. This social hierarchy, among other things about one’s class and caste, was majorly fed by how well one was able to perform their assigned gender at birth. As a young person in school, I always felt an enormous amount of pressure to fit in with the rest of “the boys.” I was never the most masculine person in my class, and I instinctively knew that the more I was able to act like all the other boys, the more seriously I would be taken as a person. I would be someone everyone admired and supported, rather than being the constant butt of everybody’s jokes. As I understood it from what I saw, being a boy meant ticking specific boxes - being good at sports and gathering “laurels” for the school, being confident and brash and bantering with the class teacher, having an obsession with football and WWE, and getting into aggressive physical fights with other boys during recess. This was how that gender was meant to be performed. As I got older, I also slowly and dimly grew into the understanding that other people weren’t necessarily “performing” their genders as much as I consciously felt I had to every day. From this grew a toxic internal monologue of constantly “faking it till you make it,” a false sort of comfort that if I put in the effort to perform, eventually, it would become practiced and come naturally to me.

I did not want to be in a space where I was once again vulnerable not only to the goading and the bullying, but also to the million other internalised societal biases around gender that came with being bullied in high school. That this person, who knew a version of me from the past that I no longer was, could disrupt my day and induce such panic so easily even after all these years, was scary and left me frustrated with my own inability to “move on” from the bullying. When I eventually responded to his message months after, I was surprised to received an instant reply. It was a long-ish message, full of buzz words like “accountability” and “self-improvement” that put my back up. To be honest, I still haven’t fully read it, and I’m not sure that I ever will. Regardless of the guilt that this person felt, I did not want the onus of his apology to fall on me. I did not want to assuage his guilt, I did not want to provide him with the comfort of “it’s okay, we were kids” (even though we were), and I certainly did not want to provide him with the closure of getting a proper reply from me. I won’t deny there was a vindictive, if petty, satisfaction leaving this person hanging. In fact, I turned my read notifications on specifically so that I could drive home the point that Yes, I have seen your little Paragraph, and I Don’t Care™. Let him wallow in his guilt for eternity, said I, in an imperious British accent in my head.In my school, much like in most other English medium schools in Mumbai, there was a very well established social hierarchy. This social hierarchy, among other things about one’s class and caste, was majorly fed by how well one was able to perform their assigned gender at birth. As a young person in school, I always felt an enormous amount of pressure to fit in with the rest of “the boys.” I was never the most masculine person in my class, and I instinctively knew that the more I was able to act like all the other boys, the more seriously I would be taken as a person. I would be someone everyone admired and supported, rather than being the constant butt of everybody’s jokes. As I understood it from what I saw, being a boy meant ticking specific boxes - being good at sports and gathering “laurels” for the school, being confident and brash and bantering with the class teacher, having an obsession with football and WWE, and getting into aggressive physical fights with other boys during recess. This was how that gender was meant to be performed. As I got older, I also slowly and dimly grew into the understanding that other people weren’t necessarily “performing” their genders as much as I consciously felt I had to every day. From this grew a toxic internal monologue of constantly “faking it till you make it,” a false sort of comfort that if I put in the effort to perform, eventually, it would become practiced and come naturally to me. I also remember having the awareness that as long as it didn’t come naturally to me, my performance was going to be a painfully obvious one. This also meant that as long as I couldn’t convince everyone else (and especially the boys) that I was naturally masculine, the bullying would not stop, nor the mean jokes, wherever I went. Especially if that wherever was a PT class where one’s perceived weakness is put even more starkly on display.I understood that acting like a boy meant being the opposite of soft – that proving my masculinity meant being aggressive. Since all of my bullies were boys, I thought that if I were to successfully bully someone else, I would also likely qualify as one. Obviously I couldn’t bully a girl, that would just be too easy, because girls back then were considered weaker and if the point of my bullying was to prove my masculinity, bullying someone weaker wouldn’t really accomplish much.My quandary of “whom to bully” was eventually answered in the form of a new addition to our class. This person, also assigned boy at birth, was like me, not discernibly strong or masculine. Unlike me, though, this person seemingly did not have any shame or hang ups about being “feminine”. In a better, kinder time, the two of us probably would have gotten closer and helped each other deal with our shared experiences.But school is not a kind time or place for most people. I had found the perfect target for my bullying. I was just as vicious with my words as the other bullies were to me. I used the same slurs, the same taunts, to hurt and degrade this other person and to prove to my classmates that I, finally, was one of them. I was no longer the other. I was now allowed to laugh along with everyone else at the ridiculous inability of this person to be manly, instead of being the one laughed at. When I look back I think it was almost as if all the things I was taught to be ashamed of in myself - my “girlish” voice, my softness, my reserved nature - were reflected back at me through this one person, and I found a twisted satisfaction in beating down on my own shame. To me, I might be feminine, but hey, “at least I was not that gay.” This person eventually left my school and transferred over to another one within one year.I do not want to dwell on the things that I did and the trauma that I inflicted. When I think of it sometimes, my reaction is to just shut those memories out immediately. I wonder if that is a way for me to protect myself from a different vulnerability than the one I was protecting in school – the vulnerability of feeling guilty. In all the times that I have stayed up at night, unable to sleep, and my thoughts have strayed to the times when I was a less than ideal person, I have quickly turned away from thoughts about my time as a bully. It was easy, almost in a sort of self-effacing way, to think about my own gendered bullying, and to pat myself on the back for blossoming into the person I am today despite it. But I never really acknowledged the same cruelty that I had tried to inflict upon someone else. So, when I received the message from my own bully, I was shaken not only because of it forced me to relive my trauma, but also because it forced me to acknowledge that I too actively was the bully to someone else. I do not know whether I feel empathy or disdain for my bully. I do not even know whether I feel both, because I do not know whether I have the capacity for such generous empathy for the source of so much trauma and pain in my life.

I also remember having the awareness that as long as it didn’t come naturally to me, my performance was going to be a painfully obvious one. This also meant that as long as I couldn’t convince everyone else (and especially the boys) that I was naturally masculine, the bullying would not stop, nor the mean jokes, wherever I went. Especially if that wherever was a PT class where one’s perceived weakness is put even more starkly on display.I understood that acting like a boy meant being the opposite of soft – that proving my masculinity meant being aggressive. Since all of my bullies were boys, I thought that if I were to successfully bully someone else, I would also likely qualify as one. Obviously I couldn’t bully a girl, that would just be too easy, because girls back then were considered weaker and if the point of my bullying was to prove my masculinity, bullying someone weaker wouldn’t really accomplish much.My quandary of “whom to bully” was eventually answered in the form of a new addition to our class. This person, also assigned boy at birth, was like me, not discernibly strong or masculine. Unlike me, though, this person seemingly did not have any shame or hang ups about being “feminine”. In a better, kinder time, the two of us probably would have gotten closer and helped each other deal with our shared experiences.But school is not a kind time or place for most people. I had found the perfect target for my bullying. I was just as vicious with my words as the other bullies were to me. I used the same slurs, the same taunts, to hurt and degrade this other person and to prove to my classmates that I, finally, was one of them. I was no longer the other. I was now allowed to laugh along with everyone else at the ridiculous inability of this person to be manly, instead of being the one laughed at. When I look back I think it was almost as if all the things I was taught to be ashamed of in myself - my “girlish” voice, my softness, my reserved nature - were reflected back at me through this one person, and I found a twisted satisfaction in beating down on my own shame. To me, I might be feminine, but hey, “at least I was not that gay.” This person eventually left my school and transferred over to another one within one year.I do not want to dwell on the things that I did and the trauma that I inflicted. When I think of it sometimes, my reaction is to just shut those memories out immediately. I wonder if that is a way for me to protect myself from a different vulnerability than the one I was protecting in school – the vulnerability of feeling guilty. In all the times that I have stayed up at night, unable to sleep, and my thoughts have strayed to the times when I was a less than ideal person, I have quickly turned away from thoughts about my time as a bully. It was easy, almost in a sort of self-effacing way, to think about my own gendered bullying, and to pat myself on the back for blossoming into the person I am today despite it. But I never really acknowledged the same cruelty that I had tried to inflict upon someone else. So, when I received the message from my own bully, I was shaken not only because of it forced me to relive my trauma, but also because it forced me to acknowledge that I too actively was the bully to someone else. I do not know whether I feel empathy or disdain for my bully. I do not even know whether I feel both, because I do not know whether I have the capacity for such generous empathy for the source of so much trauma and pain in my life.  I do, finally, allow myself to feel guilt. I do not know what to do with this guilt, because I’m sure the person I bullied does not want to go through the same things I did when I was faced with an apology. I definitely do not want to continue feeling guilty. The feeling of guilt is difficult and agonizing and forces you to live with parts of yourself that you do not want to acknowledge or revisit. However, I also know that reaching out and conveying my apology to the person I bullied is more about me than them. I understand that it is unfair to expect the victim to forgive, just so I can feel less guilty and have closure.Guilt makes one acutely vulnerable too – because you have to see yourself for who you are or have been. It would be so easy if one could see oneself as a victim of circumstance – and we could all see ourselves as victims of masculinity. But in our hearts we also know we choose our actions and the knowledge of how our vulnerability can make us violent too is not an easy one. Anshumaan (they/them) is a queer particle hoping to become a crazy cat lady by age 25. They do illustration, graphic design and drink a lot of chai in their free time.

I do, finally, allow myself to feel guilt. I do not know what to do with this guilt, because I’m sure the person I bullied does not want to go through the same things I did when I was faced with an apology. I definitely do not want to continue feeling guilty. The feeling of guilt is difficult and agonizing and forces you to live with parts of yourself that you do not want to acknowledge or revisit. However, I also know that reaching out and conveying my apology to the person I bullied is more about me than them. I understand that it is unfair to expect the victim to forgive, just so I can feel less guilty and have closure.Guilt makes one acutely vulnerable too – because you have to see yourself for who you are or have been. It would be so easy if one could see oneself as a victim of circumstance – and we could all see ourselves as victims of masculinity. But in our hearts we also know we choose our actions and the knowledge of how our vulnerability can make us violent too is not an easy one. Anshumaan (they/them) is a queer particle hoping to become a crazy cat lady by age 25. They do illustration, graphic design and drink a lot of chai in their free time.

I did not want to be in a space where I was once again vulnerable not only to the goading and the bullying, but also to the million other internalised societal biases around gender that came with being bullied in high school. That this person, who knew a version of me from the past that I no longer was, could disrupt my day and induce such panic so easily even after all these years, was scary and left me frustrated with my own inability to “move on” from the bullying. When I eventually responded to his message months after, I was surprised to received an instant reply. It was a long-ish message, full of buzz words like “accountability” and “self-improvement” that put my back up. To be honest, I still haven’t fully read it, and I’m not sure that I ever will. Regardless of the guilt that this person felt, I did not want the onus of his apology to fall on me. I did not want to assuage his guilt, I did not want to provide him with the comfort of “it’s okay, we were kids” (even though we were), and I certainly did not want to provide him with the closure of getting a proper reply from me. I won’t deny there was a vindictive, if petty, satisfaction leaving this person hanging. In fact, I turned my read notifications on specifically so that I could drive home the point that Yes, I have seen your little Paragraph, and I Don’t Care™. Let him wallow in his guilt for eternity, said I, in an imperious British accent in my head.In my school, much like in most other English medium schools in Mumbai, there was a very well established social hierarchy. This social hierarchy, among other things about one’s class and caste, was majorly fed by how well one was able to perform their assigned gender at birth. As a young person in school, I always felt an enormous amount of pressure to fit in with the rest of “the boys.” I was never the most masculine person in my class, and I instinctively knew that the more I was able to act like all the other boys, the more seriously I would be taken as a person. I would be someone everyone admired and supported, rather than being the constant butt of everybody’s jokes. As I understood it from what I saw, being a boy meant ticking specific boxes - being good at sports and gathering “laurels” for the school, being confident and brash and bantering with the class teacher, having an obsession with football and WWE, and getting into aggressive physical fights with other boys during recess. This was how that gender was meant to be performed. As I got older, I also slowly and dimly grew into the understanding that other people weren’t necessarily “performing” their genders as much as I consciously felt I had to every day. From this grew a toxic internal monologue of constantly “faking it till you make it,” a false sort of comfort that if I put in the effort to perform, eventually, it would become practiced and come naturally to me.

I did not want to be in a space where I was once again vulnerable not only to the goading and the bullying, but also to the million other internalised societal biases around gender that came with being bullied in high school. That this person, who knew a version of me from the past that I no longer was, could disrupt my day and induce such panic so easily even after all these years, was scary and left me frustrated with my own inability to “move on” from the bullying. When I eventually responded to his message months after, I was surprised to received an instant reply. It was a long-ish message, full of buzz words like “accountability” and “self-improvement” that put my back up. To be honest, I still haven’t fully read it, and I’m not sure that I ever will. Regardless of the guilt that this person felt, I did not want the onus of his apology to fall on me. I did not want to assuage his guilt, I did not want to provide him with the comfort of “it’s okay, we were kids” (even though we were), and I certainly did not want to provide him with the closure of getting a proper reply from me. I won’t deny there was a vindictive, if petty, satisfaction leaving this person hanging. In fact, I turned my read notifications on specifically so that I could drive home the point that Yes, I have seen your little Paragraph, and I Don’t Care™. Let him wallow in his guilt for eternity, said I, in an imperious British accent in my head.In my school, much like in most other English medium schools in Mumbai, there was a very well established social hierarchy. This social hierarchy, among other things about one’s class and caste, was majorly fed by how well one was able to perform their assigned gender at birth. As a young person in school, I always felt an enormous amount of pressure to fit in with the rest of “the boys.” I was never the most masculine person in my class, and I instinctively knew that the more I was able to act like all the other boys, the more seriously I would be taken as a person. I would be someone everyone admired and supported, rather than being the constant butt of everybody’s jokes. As I understood it from what I saw, being a boy meant ticking specific boxes - being good at sports and gathering “laurels” for the school, being confident and brash and bantering with the class teacher, having an obsession with football and WWE, and getting into aggressive physical fights with other boys during recess. This was how that gender was meant to be performed. As I got older, I also slowly and dimly grew into the understanding that other people weren’t necessarily “performing” their genders as much as I consciously felt I had to every day. From this grew a toxic internal monologue of constantly “faking it till you make it,” a false sort of comfort that if I put in the effort to perform, eventually, it would become practiced and come naturally to me. I also remember having the awareness that as long as it didn’t come naturally to me, my performance was going to be a painfully obvious one. This also meant that as long as I couldn’t convince everyone else (and especially the boys) that I was naturally masculine, the bullying would not stop, nor the mean jokes, wherever I went. Especially if that wherever was a PT class where one’s perceived weakness is put even more starkly on display.I understood that acting like a boy meant being the opposite of soft – that proving my masculinity meant being aggressive. Since all of my bullies were boys, I thought that if I were to successfully bully someone else, I would also likely qualify as one. Obviously I couldn’t bully a girl, that would just be too easy, because girls back then were considered weaker and if the point of my bullying was to prove my masculinity, bullying someone weaker wouldn’t really accomplish much.My quandary of “whom to bully” was eventually answered in the form of a new addition to our class. This person, also assigned boy at birth, was like me, not discernibly strong or masculine. Unlike me, though, this person seemingly did not have any shame or hang ups about being “feminine”. In a better, kinder time, the two of us probably would have gotten closer and helped each other deal with our shared experiences.But school is not a kind time or place for most people. I had found the perfect target for my bullying. I was just as vicious with my words as the other bullies were to me. I used the same slurs, the same taunts, to hurt and degrade this other person and to prove to my classmates that I, finally, was one of them. I was no longer the other. I was now allowed to laugh along with everyone else at the ridiculous inability of this person to be manly, instead of being the one laughed at. When I look back I think it was almost as if all the things I was taught to be ashamed of in myself - my “girlish” voice, my softness, my reserved nature - were reflected back at me through this one person, and I found a twisted satisfaction in beating down on my own shame. To me, I might be feminine, but hey, “at least I was not that gay.” This person eventually left my school and transferred over to another one within one year.I do not want to dwell on the things that I did and the trauma that I inflicted. When I think of it sometimes, my reaction is to just shut those memories out immediately. I wonder if that is a way for me to protect myself from a different vulnerability than the one I was protecting in school – the vulnerability of feeling guilty. In all the times that I have stayed up at night, unable to sleep, and my thoughts have strayed to the times when I was a less than ideal person, I have quickly turned away from thoughts about my time as a bully. It was easy, almost in a sort of self-effacing way, to think about my own gendered bullying, and to pat myself on the back for blossoming into the person I am today despite it. But I never really acknowledged the same cruelty that I had tried to inflict upon someone else. So, when I received the message from my own bully, I was shaken not only because of it forced me to relive my trauma, but also because it forced me to acknowledge that I too actively was the bully to someone else. I do not know whether I feel empathy or disdain for my bully. I do not even know whether I feel both, because I do not know whether I have the capacity for such generous empathy for the source of so much trauma and pain in my life.

I also remember having the awareness that as long as it didn’t come naturally to me, my performance was going to be a painfully obvious one. This also meant that as long as I couldn’t convince everyone else (and especially the boys) that I was naturally masculine, the bullying would not stop, nor the mean jokes, wherever I went. Especially if that wherever was a PT class where one’s perceived weakness is put even more starkly on display.I understood that acting like a boy meant being the opposite of soft – that proving my masculinity meant being aggressive. Since all of my bullies were boys, I thought that if I were to successfully bully someone else, I would also likely qualify as one. Obviously I couldn’t bully a girl, that would just be too easy, because girls back then were considered weaker and if the point of my bullying was to prove my masculinity, bullying someone weaker wouldn’t really accomplish much.My quandary of “whom to bully” was eventually answered in the form of a new addition to our class. This person, also assigned boy at birth, was like me, not discernibly strong or masculine. Unlike me, though, this person seemingly did not have any shame or hang ups about being “feminine”. In a better, kinder time, the two of us probably would have gotten closer and helped each other deal with our shared experiences.But school is not a kind time or place for most people. I had found the perfect target for my bullying. I was just as vicious with my words as the other bullies were to me. I used the same slurs, the same taunts, to hurt and degrade this other person and to prove to my classmates that I, finally, was one of them. I was no longer the other. I was now allowed to laugh along with everyone else at the ridiculous inability of this person to be manly, instead of being the one laughed at. When I look back I think it was almost as if all the things I was taught to be ashamed of in myself - my “girlish” voice, my softness, my reserved nature - were reflected back at me through this one person, and I found a twisted satisfaction in beating down on my own shame. To me, I might be feminine, but hey, “at least I was not that gay.” This person eventually left my school and transferred over to another one within one year.I do not want to dwell on the things that I did and the trauma that I inflicted. When I think of it sometimes, my reaction is to just shut those memories out immediately. I wonder if that is a way for me to protect myself from a different vulnerability than the one I was protecting in school – the vulnerability of feeling guilty. In all the times that I have stayed up at night, unable to sleep, and my thoughts have strayed to the times when I was a less than ideal person, I have quickly turned away from thoughts about my time as a bully. It was easy, almost in a sort of self-effacing way, to think about my own gendered bullying, and to pat myself on the back for blossoming into the person I am today despite it. But I never really acknowledged the same cruelty that I had tried to inflict upon someone else. So, when I received the message from my own bully, I was shaken not only because of it forced me to relive my trauma, but also because it forced me to acknowledge that I too actively was the bully to someone else. I do not know whether I feel empathy or disdain for my bully. I do not even know whether I feel both, because I do not know whether I have the capacity for such generous empathy for the source of so much trauma and pain in my life.  I do, finally, allow myself to feel guilt. I do not know what to do with this guilt, because I’m sure the person I bullied does not want to go through the same things I did when I was faced with an apology. I definitely do not want to continue feeling guilty. The feeling of guilt is difficult and agonizing and forces you to live with parts of yourself that you do not want to acknowledge or revisit. However, I also know that reaching out and conveying my apology to the person I bullied is more about me than them. I understand that it is unfair to expect the victim to forgive, just so I can feel less guilty and have closure.Guilt makes one acutely vulnerable too – because you have to see yourself for who you are or have been. It would be so easy if one could see oneself as a victim of circumstance – and we could all see ourselves as victims of masculinity. But in our hearts we also know we choose our actions and the knowledge of how our vulnerability can make us violent too is not an easy one. Anshumaan (they/them) is a queer particle hoping to become a crazy cat lady by age 25. They do illustration, graphic design and drink a lot of chai in their free time.

I do, finally, allow myself to feel guilt. I do not know what to do with this guilt, because I’m sure the person I bullied does not want to go through the same things I did when I was faced with an apology. I definitely do not want to continue feeling guilty. The feeling of guilt is difficult and agonizing and forces you to live with parts of yourself that you do not want to acknowledge or revisit. However, I also know that reaching out and conveying my apology to the person I bullied is more about me than them. I understand that it is unfair to expect the victim to forgive, just so I can feel less guilty and have closure.Guilt makes one acutely vulnerable too – because you have to see yourself for who you are or have been. It would be so easy if one could see oneself as a victim of circumstance – and we could all see ourselves as victims of masculinity. But in our hearts we also know we choose our actions and the knowledge of how our vulnerability can make us violent too is not an easy one. Anshumaan (they/them) is a queer particle hoping to become a crazy cat lady by age 25. They do illustration, graphic design and drink a lot of chai in their free time.