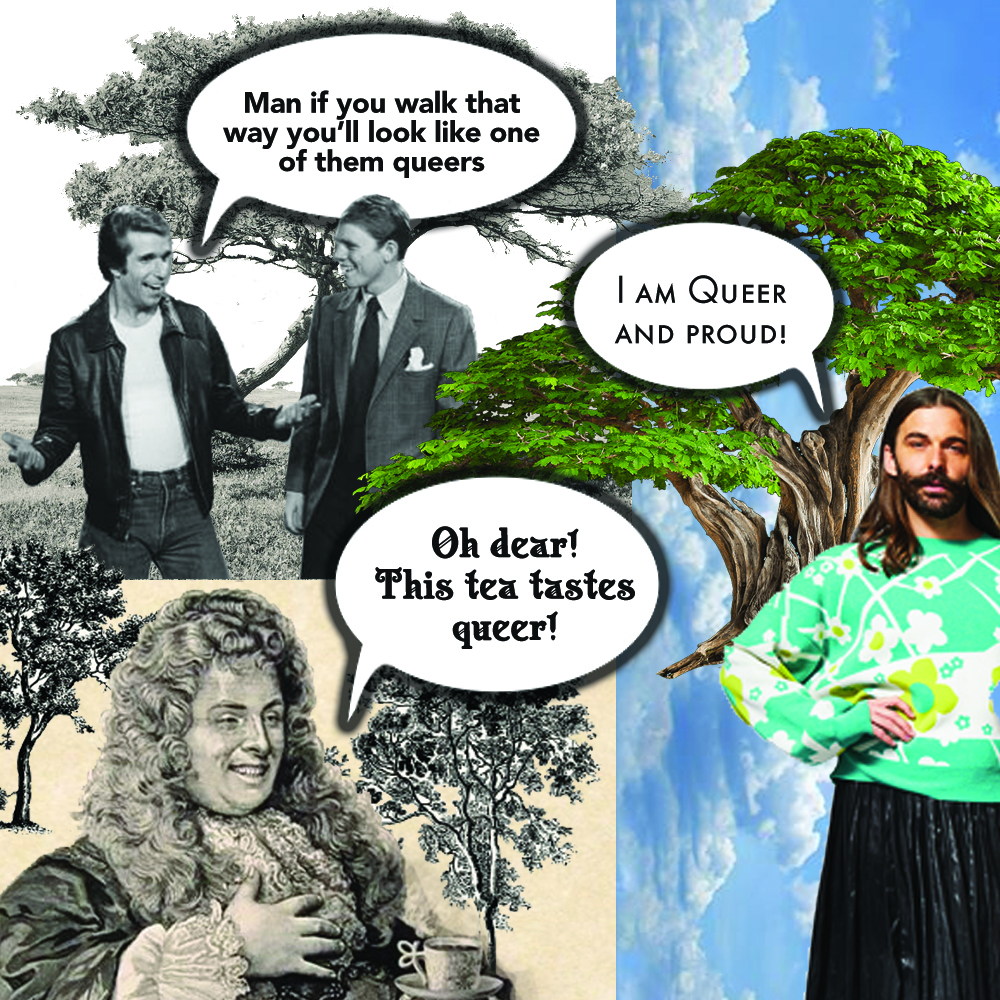

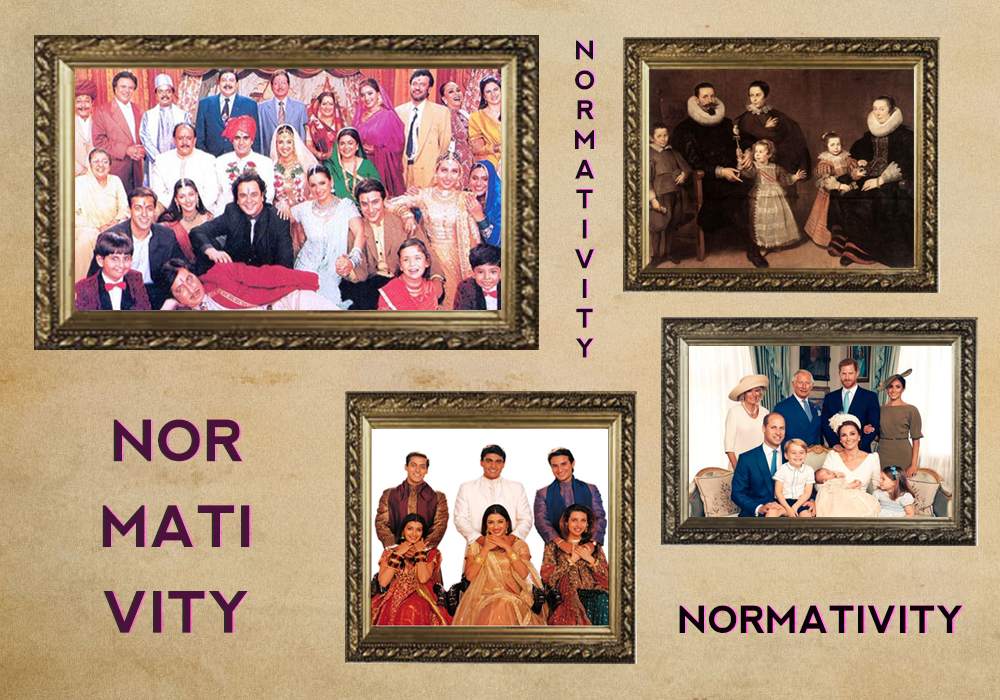

So, you’ve heard the term queer, and you think you know what it means but then do you suddenly feel a bit uncertain? Like, it seems to mean LGBT choices, but then it is also part of LGBTQI+, so is it something separate? Or you hear some people say ‘there is a difference between gay and queer’. Or at times people say ‘something’ is queer – like a film or a painting or a style element. If all this makes you feel a little shaky, worry not – your favourite agents are here with another #SuperSaralExplainer! HISTORY Idea se insult tak The word “queer” in everyday English actually means something odd, or weird, or strange – but not necessarily in a bad way. Like, “What a queer idea!” It was only in the late 19th century, that it began to be used as an insult in Britain, specifically for gay men or men who seemed ‘effeminate’.  You know the famous author and playwright, Oscar Wilde? He makes a guest appearance in the story of the first time ‘queer’ came to be recorded as a written insult referring to gay men. The Marquess of Queensberry – a man named John Douglas – found out that one of his sons was in a relationship with a man. In 1894, he wrote a letter disparaging “Snob Queers” to his other son, who, it turns out, was also in a gay relationship… with none other than Oscar Wilde! Douglas was furious and insulted Wilde, who sued him for libel, and later dropped the case. But this was only the start of a legal feud between them that led to Wilde’s ruin. Douglas’ letter with the term ‘queer’ emerged during the court cases. Over time, more and more people began to use the word as an abuse or pejorative. Turning an insult inside-out and turning the world ulta-pulta Roughly around the 1980s, LGBT activists began to reclaim the word for themselves. Matlab – instead of accepting the idea that being different was a bad thing and demanding that they not be called that, they turned the idea inside out. Being different was something to celebrate. Queer was upheld as a word that stood for a powerful and creative rejection of normativity. (Yes, we know you are thinking – yaar, so much English! Normativity kya hai? Normativity means deciding that only certain things are ‘normal’ or acceptable in society, whether it’s dressing a certain way or forming certain defined relationships. For example, love, sex and marriage are considered normal only between a man and a woman, or, everyone is expected to be married eventually. So any other choices – like a romantic relationship between two women, for instance – are seen as abnormal and inappropriate, and so, not normative.)

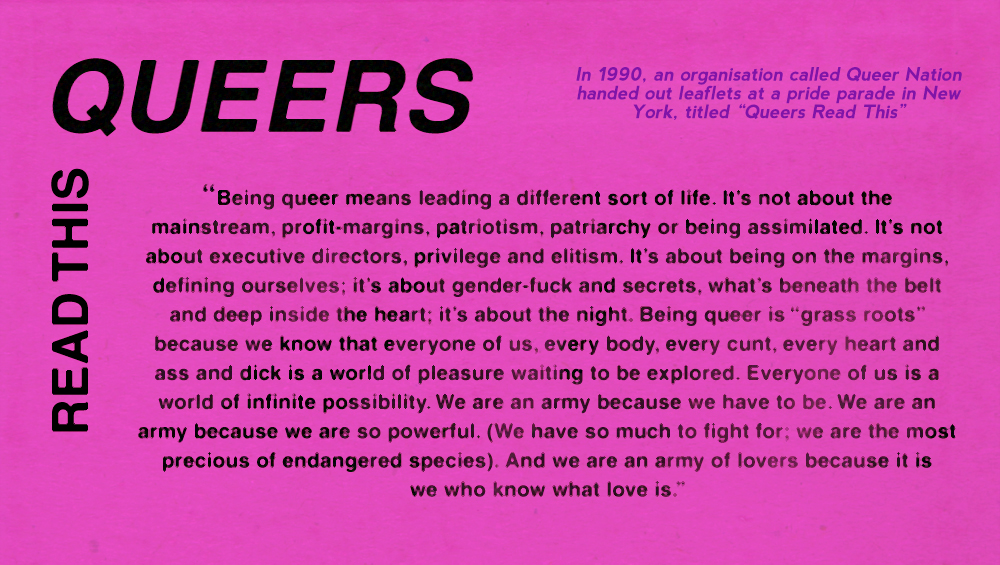

You know the famous author and playwright, Oscar Wilde? He makes a guest appearance in the story of the first time ‘queer’ came to be recorded as a written insult referring to gay men. The Marquess of Queensberry – a man named John Douglas – found out that one of his sons was in a relationship with a man. In 1894, he wrote a letter disparaging “Snob Queers” to his other son, who, it turns out, was also in a gay relationship… with none other than Oscar Wilde! Douglas was furious and insulted Wilde, who sued him for libel, and later dropped the case. But this was only the start of a legal feud between them that led to Wilde’s ruin. Douglas’ letter with the term ‘queer’ emerged during the court cases. Over time, more and more people began to use the word as an abuse or pejorative. Turning an insult inside-out and turning the world ulta-pulta Roughly around the 1980s, LGBT activists began to reclaim the word for themselves. Matlab – instead of accepting the idea that being different was a bad thing and demanding that they not be called that, they turned the idea inside out. Being different was something to celebrate. Queer was upheld as a word that stood for a powerful and creative rejection of normativity. (Yes, we know you are thinking – yaar, so much English! Normativity kya hai? Normativity means deciding that only certain things are ‘normal’ or acceptable in society, whether it’s dressing a certain way or forming certain defined relationships. For example, love, sex and marriage are considered normal only between a man and a woman, or, everyone is expected to be married eventually. So any other choices – like a romantic relationship between two women, for instance – are seen as abnormal and inappropriate, and so, not normative.)  Opening up a huge umbrella, singing in the rain In 1990, an organisation called Queer Nation handed out leaflets at a pride parade in New York, titled “Queers Read This”, in which they explained that they were using the term in reclamation and pride, and to refer to a wider community that wasn’t centred on just gay men. “Queer, unlike GAY, doesn’t mean MALE,” it read. In the leaflet, the members of Queer Nation expressed anger that people from the LGBT community were the targets of shaming and violence, and wanted to fight that with pride and assertion, and violence too, if needed. They were controversial then because of their confrontational tactics – and still are today. But in that pamphlet, they weren’t just calling for action against people who attacked them, or for more people to join them. They also put down some ideas about what being queer itself meant, not just as an expression of gender or sexuality that wasn’t considered ‘normal’, but as an expansive philosophy too:

Opening up a huge umbrella, singing in the rain In 1990, an organisation called Queer Nation handed out leaflets at a pride parade in New York, titled “Queers Read This”, in which they explained that they were using the term in reclamation and pride, and to refer to a wider community that wasn’t centred on just gay men. “Queer, unlike GAY, doesn’t mean MALE,” it read. In the leaflet, the members of Queer Nation expressed anger that people from the LGBT community were the targets of shaming and violence, and wanted to fight that with pride and assertion, and violence too, if needed. They were controversial then because of their confrontational tactics – and still are today. But in that pamphlet, they weren’t just calling for action against people who attacked them, or for more people to join them. They also put down some ideas about what being queer itself meant, not just as an expression of gender or sexuality that wasn’t considered ‘normal’, but as an expansive philosophy too:  Understood like this the term ‘queer’, even today, is considered by many to be radical and inclusive – not just a statement of sexuality, but a desire to celebrate everything that is considered un-fit or unfitting by society just because it does not conform to conventions – whether it comes to behaviour, to what gender or sexuality we are, how to love, make art or fashion or decide what matters. When queer is a theory it que(e)ries everything else! In the 1990s, “queer theory” developed through the work of feminists like Judith Butler, Eve Sedgewick, Teresa de Lauretis and Jack Halberstam. It used gender and sexuality to examine structures of power, tangible and intangible.

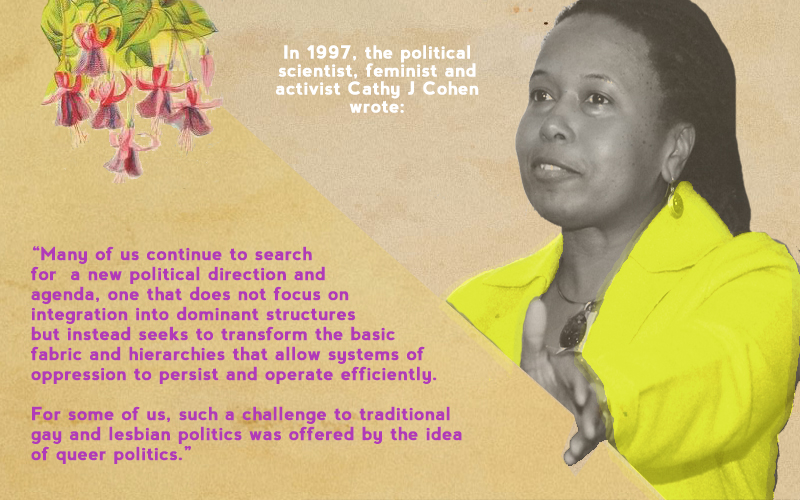

Understood like this the term ‘queer’, even today, is considered by many to be radical and inclusive – not just a statement of sexuality, but a desire to celebrate everything that is considered un-fit or unfitting by society just because it does not conform to conventions – whether it comes to behaviour, to what gender or sexuality we are, how to love, make art or fashion or decide what matters. When queer is a theory it que(e)ries everything else! In the 1990s, “queer theory” developed through the work of feminists like Judith Butler, Eve Sedgewick, Teresa de Lauretis and Jack Halberstam. It used gender and sexuality to examine structures of power, tangible and intangible.

Image Source

Queer politics expanded the ideas mentioned in the Queer Nation pamphlet to not only look at sex, sexuality and gender, but, to use these understandings to question other things too. So, for example, it encourages us to question not just personal freedoms and why only some people have the right to choose their sexual partner, but also question why governments have traditionally upheld heterosexuality as their model for the ideal citizen – in many countries, only heterosexual marriage is recognised, and inheritance rights, for example, apply in many cases only to married spouses without taking into account people in long-term relationships who are not married. Writer and academic John D’Emilio wrote in 1983 that one way to break this emphasis on families and marginalising all others was to create alternative structures of community – of housing, daycare, medical facilities – that “enlarge the social unit where each of us has a secure place. As we create structures beyond the nuclear family that provide a sense of belonging, the family will wane in significance. Less and less it will seem to make or break our emotional security.” He saw the building of support networks that were not based on ties of blood or state sanction, like the kind built by queer people, as an important and necessary political aim. In an essay about queer art, the writer and performer Cassie Peterson writes that instead of trying to fit into a gay and lesbian agenda that wanted to assimilate into the mainstream, “Queer is a radicalised politic and aesthetic practice that is more interested in diversifying the ways in which things come into being, rather than just working to include a greater diversity of people into the way things already are. Queer – movement out of stasis. Out of status quo.” In lived terms, as the cult filmmaker and comedian John Waters once joked about resisting assimilation:

Image Source

In a talk in 2019, the author, academic and queer activist R Raj Rao said:

Image Source

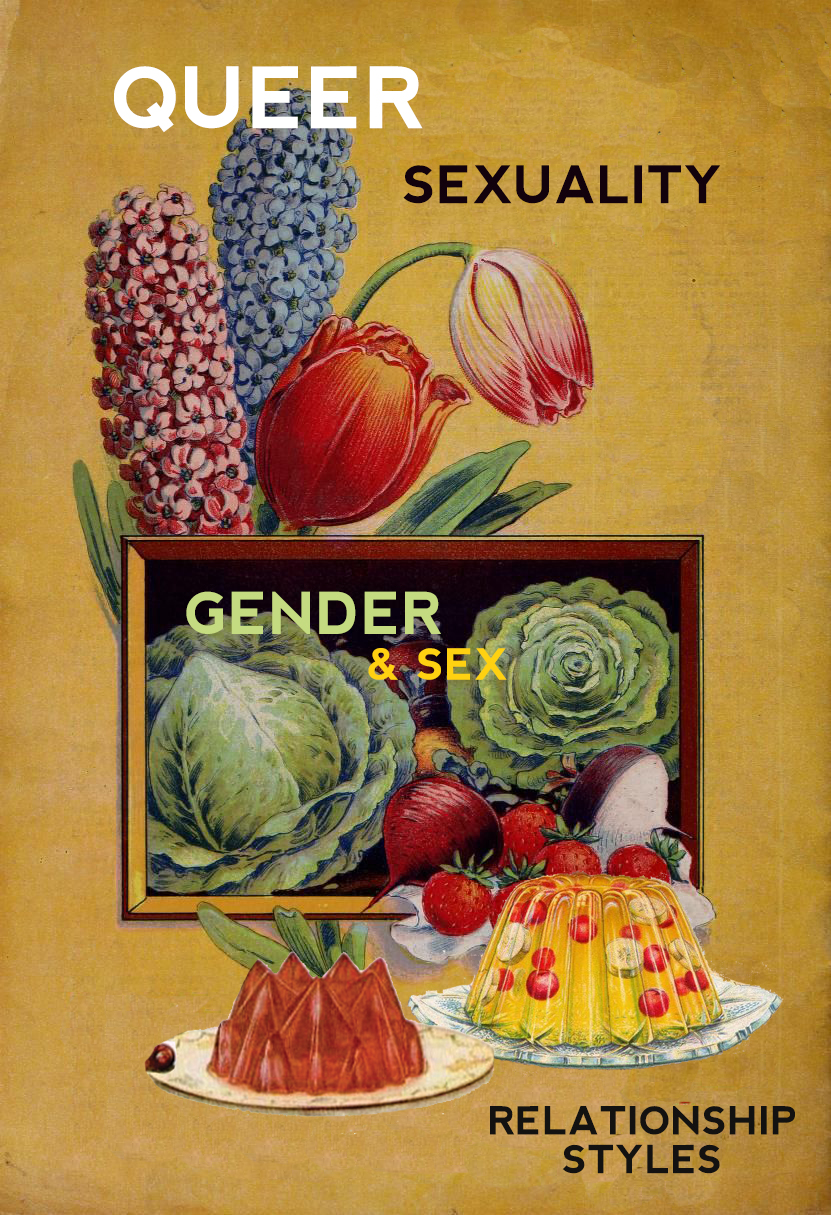

Queering Things ‘Queering’ something means to question the norm, and to question dominant power structures. For some, turning things ulta-pulta means recognising and accepting that big changes in the world are directly connected to small changes at a personal level – freedom to express oneself how one wants, freedom to love who one wants, freedom to have sex with someone who wants to have sex with you, and many more such freedoms. It also means accepting that we are all different, and that it is a good thing, not something to be afraid of or ashamed of. After all you know that saying, na, Variety is the Spice of Life! For many, being queer also means putting love and pleasure and fun at the centre of everything we do or treating the serious irreverently and taking what is considered trivial seriously. SO – IS EVERYONE QUEER? Not everyone is queer, nor claims to be, though people might have a queer element in their lives. For now, queer is used in a few contexts.  SEX AND GENDER IDENTITY We usually grow up being told that all people are either male or female – and that having a female body (aka breasts and a vagina) means that you must be a woman, and having a male body (aka a penis) means that you must be a man. But not everyone has a body that fits neatly into one sex. And not everyone is cisgender – matlab, people whose gender identity is the same as the bodies they were born with. Gender identity is now seen in a number of ways that isn’t always biological. And biological sex isn't limited to the binary.

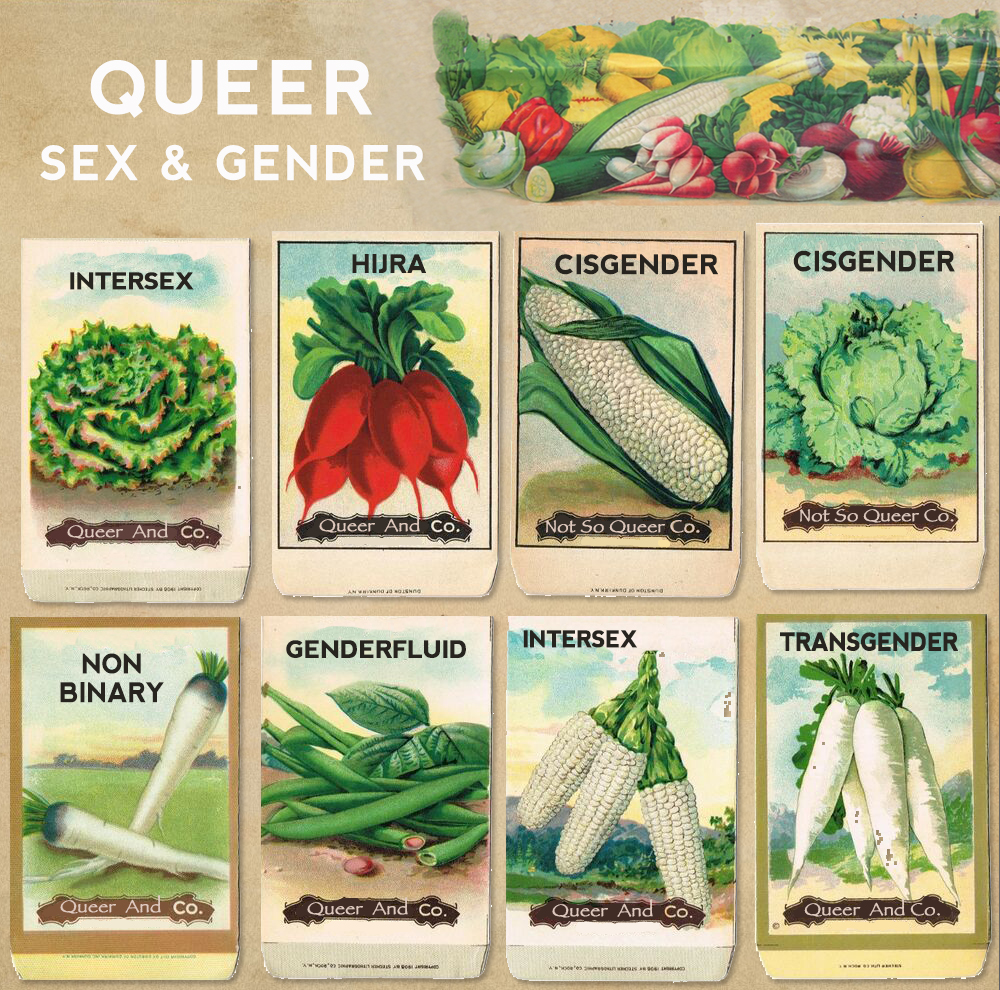

SEX AND GENDER IDENTITY We usually grow up being told that all people are either male or female – and that having a female body (aka breasts and a vagina) means that you must be a woman, and having a male body (aka a penis) means that you must be a man. But not everyone has a body that fits neatly into one sex. And not everyone is cisgender – matlab, people whose gender identity is the same as the bodies they were born with. Gender identity is now seen in a number of ways that isn’t always biological. And biological sex isn't limited to the binary.

- Intersex: A person who was born with some biological characteristics that are considered male, as well as some that are considered female. These characteristics are not restricted to genitalia – it could extend to variations in chromosomes or gonads or other aspects too.

- Transgender: People who do not identify with the gender they were given when they were born. Trans-men and trans-women may seek surgery and hormone therapy to change their genitalia and physical appearance, but not everyone does.

- Hijras: People in India and parts of South Asia with a specific cultural identity, many of whom identify as a “third gender”. There are many such groups in South Asia – such as Kinnars, Aravanis, Jogappas and so on – each with their own regional identities and traditions.

- Gender fluid (or genderqueer or non-binary): The term for having an identity that is not only masculine or only feminine. As the the term ‘fluid’ suggests, there is no strict identification with gender – some may feel like they belong to more than one gender at the same time, or have no gender at all, or fluctuate among genders from time to time.

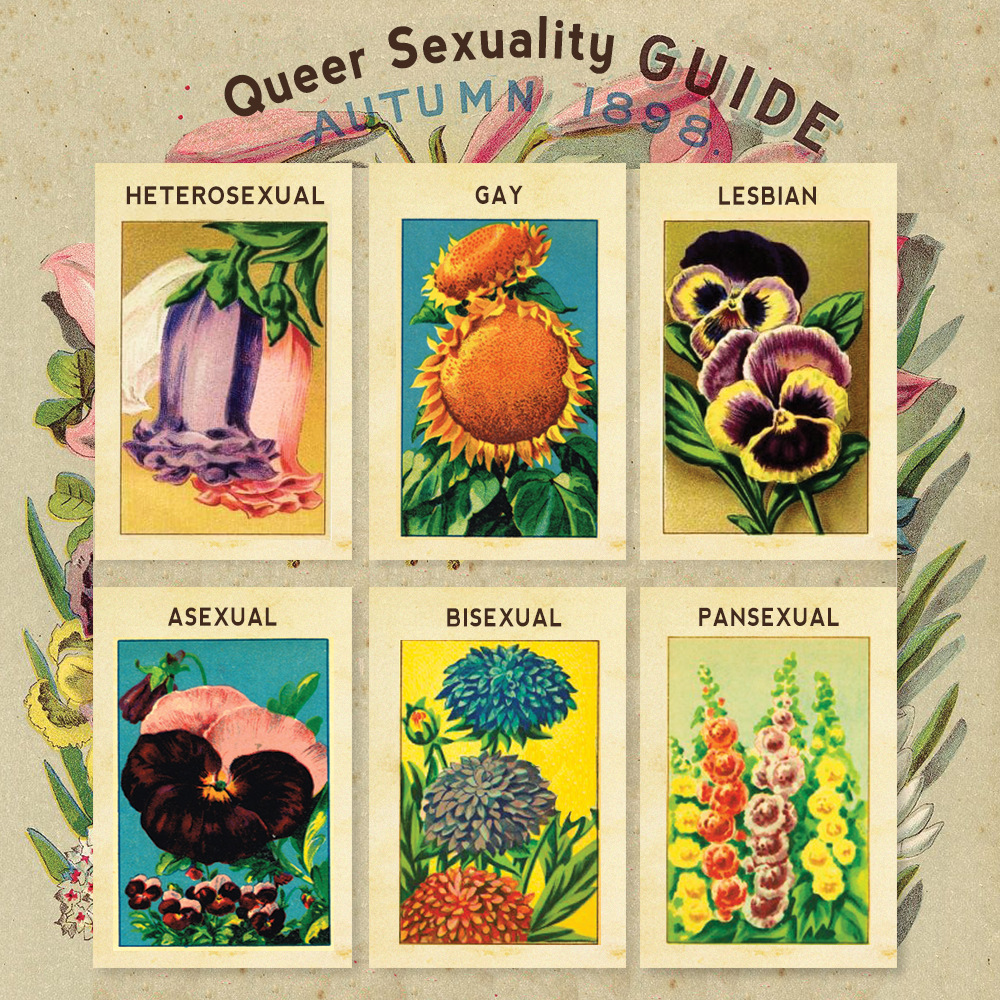

SEXUAL ORIENTATIONS Heterosexual monogamy is considered the norm – socially and by law, though that is changing. As gender itself is now seen much more diversely, so is the idea of who might be attracted to whom. Here are some kinds of sexual orientations: Homosexual: Sexual attraction between a man and another man (in which case they are said to be gay) or a woman and a woman (in which case they might be called lesbian). Bisexual or Bi: Sexual attraction to two genders. Pansexual: Sexual attraction irrespective of sex and gender. Asexual: A spectrum of identities in which people do not have sexual desires. This can include people who may want a romantic relationship with another person but not a sexual one, or people who might have sex occasionally with a partner, or even people who have no desire for either a romantic or sexual relationship, no matter what their sexual orientation is.

SEXUAL ORIENTATIONS Heterosexual monogamy is considered the norm – socially and by law, though that is changing. As gender itself is now seen much more diversely, so is the idea of who might be attracted to whom. Here are some kinds of sexual orientations: Homosexual: Sexual attraction between a man and another man (in which case they are said to be gay) or a woman and a woman (in which case they might be called lesbian). Bisexual or Bi: Sexual attraction to two genders. Pansexual: Sexual attraction irrespective of sex and gender. Asexual: A spectrum of identities in which people do not have sexual desires. This can include people who may want a romantic relationship with another person but not a sexual one, or people who might have sex occasionally with a partner, or even people who have no desire for either a romantic or sexual relationship, no matter what their sexual orientation is.  RELATIONSHIP STYLES AND EMOTIONAL APPROACHES Marriage and monogamy are considered the standard in heterosexual relationships. But there are several ways of forming relationships that may not have to do with marriage, be restricted to coupledom or or be restricted to forming a couple. Here are some of them:

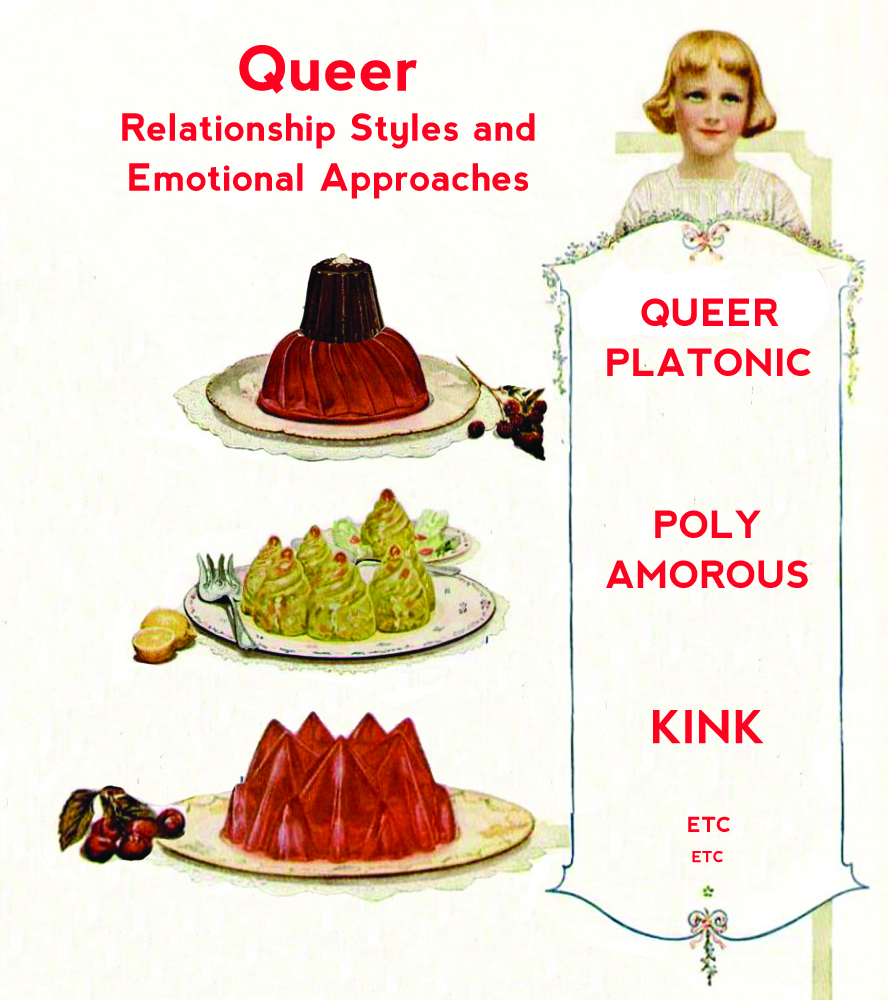

RELATIONSHIP STYLES AND EMOTIONAL APPROACHES Marriage and monogamy are considered the standard in heterosexual relationships. But there are several ways of forming relationships that may not have to do with marriage, be restricted to coupledom or or be restricted to forming a couple. Here are some of them:  Polyamorous relationships and open relationships: Relationships in which a person has more than one lover, with the consent of all partners. Queerplatonic relationships: Relationships between two people of the same sex who have an intense bond that seems to go beyond what we might usually think of as friendship, though it is not romantic or sexual. Kink: This refers to sexual desires and practices, or even fantasies, that are non-traditional. This could include bondage, domination/submission or group sex, for instance. Swinging: When people in a committed relationship consensually have sex with others. Relationship anarchy: When there is freedom and spontaneity in all romantic and sexual relations, and there is no hierarchy or partners and non-partners. Emotional fidelity: Where partners decide to keep emotional intimacy exclusive to their relationship, but physical intimacy may happen outside of it. For kinds of approaches to relationships, check out this and this. CAN STRAIGHT PEOPLE BE QUEER? This is often debated but many say, yes, if they do not participate in normative relationship styles, emotional approaches or gender presentation. Some, on the other hand, feel that straight people identifying with the term dilutes LGBT identity, as it allows straight people to claim elements of LGBT identity that are considered ‘cool’, without also having to deal with the shaming and persecution that LGBT people face. The controversial term “queer heterosexual” refers to people who may be heterosexual in orientation, but queer in outlook. At a 1997 conference on sexuality in Amsterdam, dancer Clyde Smith, who used this term to describe himself, said: “Not only was I learning that things are not as they seem and that human sexual activities are complex in ways that go beyond labels such as gay and straight but that many if not most of us have unrevealed potentials for experimentation. […] I claim the identity of queer heterosexual in order to further my own desires for a world of multiple possibilities rather than as a means of benefiting from queer chic.” Some straight artists may not claim the term, but are still considered queer icons for their transgressive art. Take Madonna, for instance. The author Matt Cain writes about what the singer and performer Madonna’s out-there performances meant to him: “People forget the role Madonna played in opening up gay culture to the mainstream. She wasn’t gay herself, but from the beginning she talked about how gay people were part of her life: her gay mentor, her dance teacher, Christopher Flynn; the artists and photographers she hung around with like Keith Haring and Herb Ritts; the gay dancers she paraded around so proudly in the film In Bed With Madonna. You cannot imagine what it was like to witness her doing that when you were being mercilessly bullied about your sexuality at school, as I was.” For many, it is a person’s way of living, ultimately, that appears to count as queer, rather than their identity. AESTHETICS AND STYLE

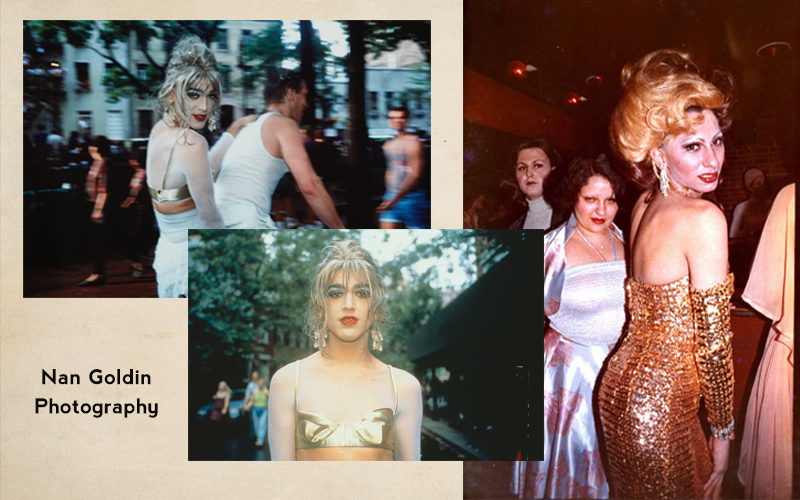

Polyamorous relationships and open relationships: Relationships in which a person has more than one lover, with the consent of all partners. Queerplatonic relationships: Relationships between two people of the same sex who have an intense bond that seems to go beyond what we might usually think of as friendship, though it is not romantic or sexual. Kink: This refers to sexual desires and practices, or even fantasies, that are non-traditional. This could include bondage, domination/submission or group sex, for instance. Swinging: When people in a committed relationship consensually have sex with others. Relationship anarchy: When there is freedom and spontaneity in all romantic and sexual relations, and there is no hierarchy or partners and non-partners. Emotional fidelity: Where partners decide to keep emotional intimacy exclusive to their relationship, but physical intimacy may happen outside of it. For kinds of approaches to relationships, check out this and this. CAN STRAIGHT PEOPLE BE QUEER? This is often debated but many say, yes, if they do not participate in normative relationship styles, emotional approaches or gender presentation. Some, on the other hand, feel that straight people identifying with the term dilutes LGBT identity, as it allows straight people to claim elements of LGBT identity that are considered ‘cool’, without also having to deal with the shaming and persecution that LGBT people face. The controversial term “queer heterosexual” refers to people who may be heterosexual in orientation, but queer in outlook. At a 1997 conference on sexuality in Amsterdam, dancer Clyde Smith, who used this term to describe himself, said: “Not only was I learning that things are not as they seem and that human sexual activities are complex in ways that go beyond labels such as gay and straight but that many if not most of us have unrevealed potentials for experimentation. […] I claim the identity of queer heterosexual in order to further my own desires for a world of multiple possibilities rather than as a means of benefiting from queer chic.” Some straight artists may not claim the term, but are still considered queer icons for their transgressive art. Take Madonna, for instance. The author Matt Cain writes about what the singer and performer Madonna’s out-there performances meant to him: “People forget the role Madonna played in opening up gay culture to the mainstream. She wasn’t gay herself, but from the beginning she talked about how gay people were part of her life: her gay mentor, her dance teacher, Christopher Flynn; the artists and photographers she hung around with like Keith Haring and Herb Ritts; the gay dancers she paraded around so proudly in the film In Bed With Madonna. You cannot imagine what it was like to witness her doing that when you were being mercilessly bullied about your sexuality at school, as I was.” For many, it is a person’s way of living, ultimately, that appears to count as queer, rather than their identity. AESTHETICS AND STYLE  What is queer aesthetics? One meaning of term evolved in the 1980s and usually refers to art that uses queer imagery. It was shaped by the times, which saw feminist debates as well as the AIDS crisis. An example of this which is often referred to is Nan Goldin’s photography of people of ambiguous gender.

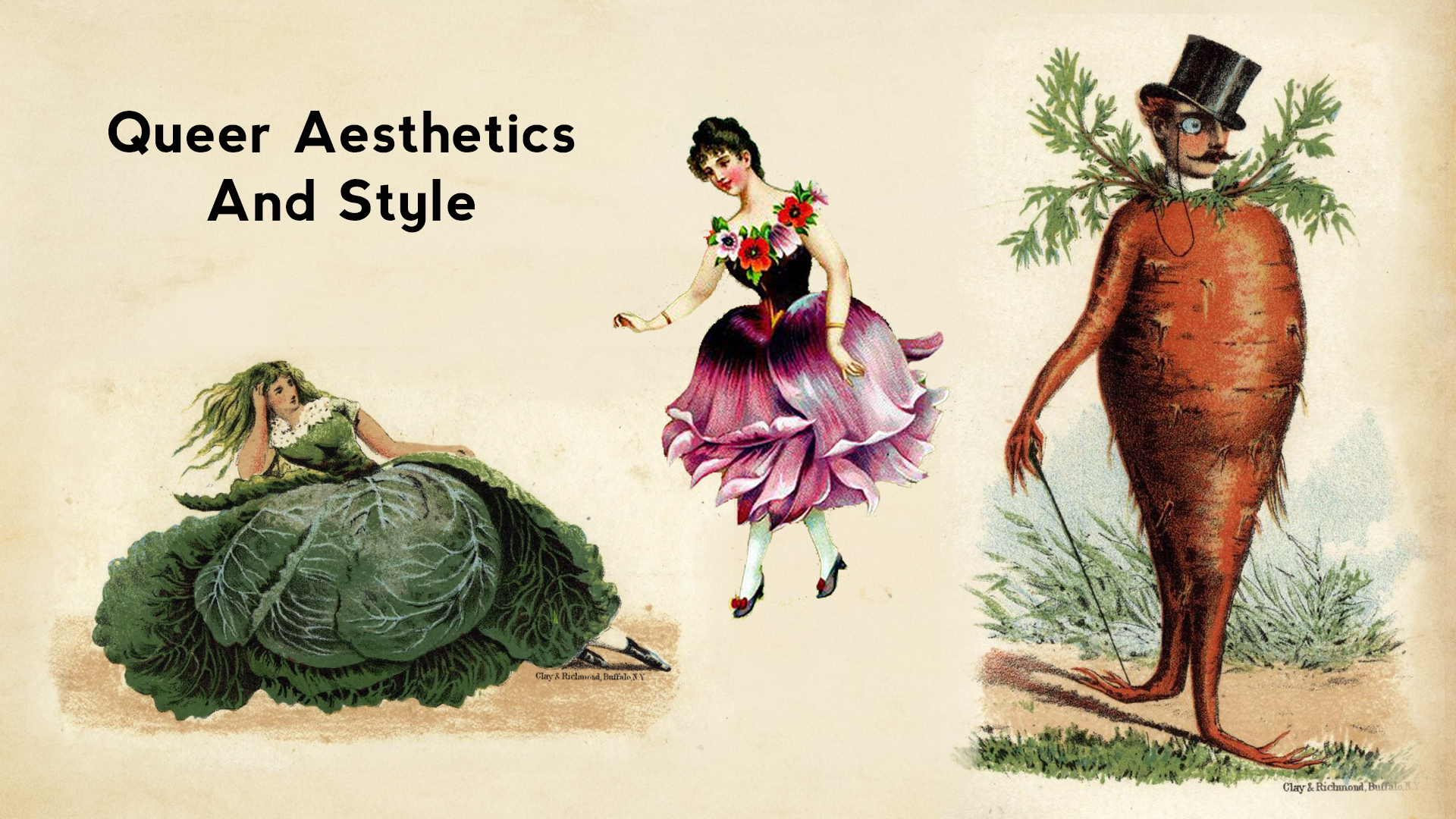

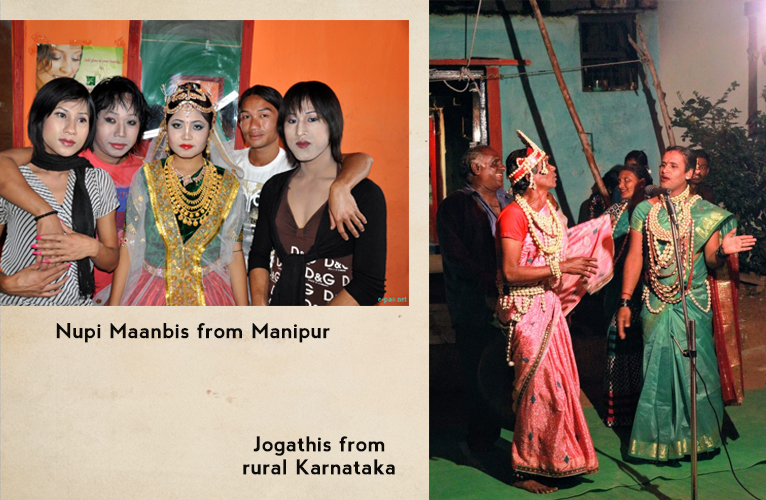

What is queer aesthetics? One meaning of term evolved in the 1980s and usually refers to art that uses queer imagery. It was shaped by the times, which saw feminist debates as well as the AIDS crisis. An example of this which is often referred to is Nan Goldin’s photography of people of ambiguous gender.  Queer aesthetics and style are are also about rejecting normativity, portraying queer politics, and mixing categories – mashing together popular and high art, fiction and non-fiction, the political and the pleasurable. Every culture has forms which reflect a queer aesthetic or approach. And it isn’t just in urban areas that different kinds of desi queer aesthetics exist – the lively songs of jogathis about the Goddess Yellamma sung in rural Karnataka, the male tamasha performers who tour Maharashtra to perform lavani, a dance usually done by women, and the nupi maanbis of Manipur who perform on stage in shumang leela troupes, all play with and question the boundaries of gender, respectability, and identity.

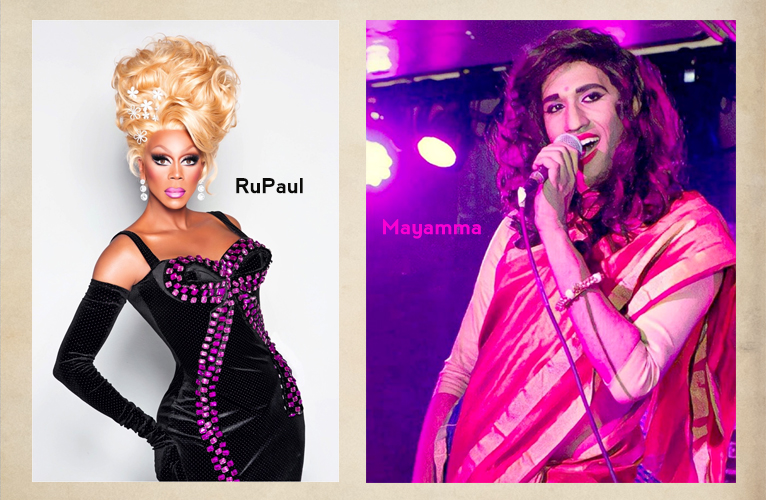

Queer aesthetics and style are are also about rejecting normativity, portraying queer politics, and mixing categories – mashing together popular and high art, fiction and non-fiction, the political and the pleasurable. Every culture has forms which reflect a queer aesthetic or approach. And it isn’t just in urban areas that different kinds of desi queer aesthetics exist – the lively songs of jogathis about the Goddess Yellamma sung in rural Karnataka, the male tamasha performers who tour Maharashtra to perform lavani, a dance usually done by women, and the nupi maanbis of Manipur who perform on stage in shumang leela troupes, all play with and question the boundaries of gender, respectability, and identity.  Here are some kinds of art that are considered part of a queer aesthetic – but the term is used for many forms that bend categories: Queercore: A sub-culture that originated in punk of the 1980s and included music, film, writing, and magazines characterised by a do-it-yourself style. Bands like Team Dresch, an all-lesbian American punk rock band, represent this genre. Drag: The practice of dressing up as another gender as part of a performance. The costumes and make-up in drag are usually brightly coloured and over-the-top, with an exaggerated performance of gender. (Did you know that the practice of applying contouring make-up, which everyone uses today from Kim Kardashian to Rakhi Sawant, originates from drag queens? So does the practice of using exaggerated eyelash extensions!)

Here are some kinds of art that are considered part of a queer aesthetic – but the term is used for many forms that bend categories: Queercore: A sub-culture that originated in punk of the 1980s and included music, film, writing, and magazines characterised by a do-it-yourself style. Bands like Team Dresch, an all-lesbian American punk rock band, represent this genre. Drag: The practice of dressing up as another gender as part of a performance. The costumes and make-up in drag are usually brightly coloured and over-the-top, with an exaggerated performance of gender. (Did you know that the practice of applying contouring make-up, which everyone uses today from Kim Kardashian to Rakhi Sawant, originates from drag queens? So does the practice of using exaggerated eyelash extensions!)  Camp: The writer and philosopher Susan Sontag describes the “essence” of camp as being “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Camp is an aesthetic that enjoys things that might be thought of as over-the-top or in bad taste – what the film scholar Richard Dyer calls “irony, exaggeration, trivialisation, theatricalisation and an ambivalent making fun of and out of the serious and respectable." Lots of people have tried to nail down what queer art is – is it something made only by people who are queer? Or people of any orientation but whose approach is queer? What defines it? Peterson writes that actually, it can’t be defined in a narrow sense, as there is no “essential queer art or subject”. Rather, Peterson sees it as “a contrast against which normalcy is produced and codified,” and “[a] strategy. A practice. And a disruption to business-as-usual.” For image sources, please follow the hyperlinks: RuPaul, Nupi Maanbis, Jogathis, Mayamma. For more reading, check out the following books and links: “The ‘Queer’ Queer-y: Violent Slur Or The Language Of Liberation?” by Justina Ashman No Outlaws in the Gender Galaxy by Chayanika Shah, Raj Merchant, Shals Mahajan, Smriti Nevatia “What It Means To Be Asexual, Bicurious — & Other Sexualities You Need To Know” by Kasandra Brabaw Criminal Love?: Queer Theory, Culture, and Politics in India by R Raj Rao “Contemporary Art and Queer Aesthetics” by Jarrett Earnest "Notes on Camp" by Susan Sontag “How I Became a Queer Heterosexual” by Clyde Smith “Capitalism and Gay Identity” by John D’Emilio “Punks, Bulldagger and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” by Cathy J Cohen "Critically Queer" by Judith Butler

Camp: The writer and philosopher Susan Sontag describes the “essence” of camp as being “its love of the unnatural: of artifice and exaggeration.” Camp is an aesthetic that enjoys things that might be thought of as over-the-top or in bad taste – what the film scholar Richard Dyer calls “irony, exaggeration, trivialisation, theatricalisation and an ambivalent making fun of and out of the serious and respectable." Lots of people have tried to nail down what queer art is – is it something made only by people who are queer? Or people of any orientation but whose approach is queer? What defines it? Peterson writes that actually, it can’t be defined in a narrow sense, as there is no “essential queer art or subject”. Rather, Peterson sees it as “a contrast against which normalcy is produced and codified,” and “[a] strategy. A practice. And a disruption to business-as-usual.” For image sources, please follow the hyperlinks: RuPaul, Nupi Maanbis, Jogathis, Mayamma. For more reading, check out the following books and links: “The ‘Queer’ Queer-y: Violent Slur Or The Language Of Liberation?” by Justina Ashman No Outlaws in the Gender Galaxy by Chayanika Shah, Raj Merchant, Shals Mahajan, Smriti Nevatia “What It Means To Be Asexual, Bicurious — & Other Sexualities You Need To Know” by Kasandra Brabaw Criminal Love?: Queer Theory, Culture, and Politics in India by R Raj Rao “Contemporary Art and Queer Aesthetics” by Jarrett Earnest "Notes on Camp" by Susan Sontag “How I Became a Queer Heterosexual” by Clyde Smith “Capitalism and Gay Identity” by John D’Emilio “Punks, Bulldagger and Welfare Queens: The Radical Potential of Queer Politics?” by Cathy J Cohen "Critically Queer" by Judith Butler