“It’s simple, to live life emotions are very important so why should you suppress them?” Lesbian Love and Freedom Journeys with Maya Sharma

An interview with Maya Sharma

Illustrated by Shikha Sreenivas

Maya Sharma is a feminist and queer activist who is a part of the Indian Women’s Movement. She was born in Rajasthan and went on to study literature in Delhi. Her life changed radically when she came in contact with the Indian Women’s Movement and activism. She chose to leave her domestic life as a housewife in an urban middle class home and become an activist. It was the work she did here with people from Delhi’s resettlement colonies and working class women across India that brought the paper and pen together for her. She has co-authored a book on Single Women in Hindi and a path-breaking piece of work “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India” published in 2006. This book was a collection of ten stories of working class queer women, following their stories and their unique voices. The book is a unique work that brings together story and research, to show us a glimpse of the world of women loving women in working class India - and through it also opened up a multi-layered meditation on life, love and feminism for all of us. Currently, she is working with LBT community in Vikalp (Women’s Group) Vadodara. This interview is based on two conversations at different times that we, at Agents of Ishq, had with Maya Sharma. They have been lightly edited for clarity. What was your journey of becoming an activist, and then to having the conversations about sexuality, identity and gender that led to your book, “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged in India”? The best thing I discovered when I began working in the bastis and resettlement colonies, while talking to the women there is that they, who live so-called “non-political lives”, are able to talk about their lives the exact way in which they’re living them. We are not not able to speak in the same way, with the same simplicity. Maybe we have studied too much because of which our lives have moved far away from the real thing. Our lives are filled with impressing people, dressing up, going out… But there is a difference between the way in which these women get ready and we get ready. The women in the slum used to say that there are two kinds of hunger, one of the womb and the other of the stomach (ek kok ki bhook, ek pet ke bhook). When they say womb, it is expressive of sensualness, sexual desire. That’s why they’re so in touch with their lives and feelings. This realisation was so unique and important for me and it helped me in knowing many unknown things and learning a lot from them.

Maya Sharma is a feminist and queer activist who is a part of the Indian Women’s Movement. She was born in Rajasthan and went on to study literature in Delhi. Her life changed radically when she came in contact with the Indian Women’s Movement and activism. She chose to leave her domestic life as a housewife in an urban middle class home and become an activist. It was the work she did here with people from Delhi’s resettlement colonies and working class women across India that brought the paper and pen together for her. She has co-authored a book on Single Women in Hindi and a path-breaking piece of work “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India” published in 2006. This book was a collection of ten stories of working class queer women, following their stories and their unique voices. The book is a unique work that brings together story and research, to show us a glimpse of the world of women loving women in working class India - and through it also opened up a multi-layered meditation on life, love and feminism for all of us. Currently, she is working with LBT community in Vikalp (Women’s Group) Vadodara. This interview is based on two conversations at different times that we, at Agents of Ishq, had with Maya Sharma. They have been lightly edited for clarity. What was your journey of becoming an activist, and then to having the conversations about sexuality, identity and gender that led to your book, “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged in India”? The best thing I discovered when I began working in the bastis and resettlement colonies, while talking to the women there is that they, who live so-called “non-political lives”, are able to talk about their lives the exact way in which they’re living them. We are not not able to speak in the same way, with the same simplicity. Maybe we have studied too much because of which our lives have moved far away from the real thing. Our lives are filled with impressing people, dressing up, going out… But there is a difference between the way in which these women get ready and we get ready. The women in the slum used to say that there are two kinds of hunger, one of the womb and the other of the stomach (ek kok ki bhook, ek pet ke bhook). When they say womb, it is expressive of sensualness, sexual desire. That’s why they’re so in touch with their lives and feelings. This realisation was so unique and important for me and it helped me in knowing many unknown things and learning a lot from them. I would like to talk about Bhanvari. I learned a lot from her. She was a 60 year old woman and I was working in Delhi at that time. When I used to visit slums, that 60 year old woman told me that there were two women and the love between them was very deep, you also call it “one soul and two bodies”. The relationship was that strong. As we started meeting more frequently, she also confessed that she was in a relationship with the woman her husband was seeing. When I heard her story, it just stunned me. I used to think that there should be some moral values, one man-one woman. To understand this kind of relationship was difficult for me, I was in a dilemma. Since I too was in a similar situation that challenged all my ideas of moral values and marriage, I learnt a lot from her. After being married for 10 years, I fell in love with a woman. In fact, I fell in love with two women at the same time. To keep love bound and locked within yourself is difficult. Even though I’ve had experiences and loved women in school, I didn’t know living this life could be a reality. Because in a middle class upbringing, you are constantly pressured about getting married and having children. For the first time in my comfortable middle class life, I found the space for being able to talk about and express love and sexual desire. Earlier I used to think that love is bound by age and marriage. I’d never had the opportunity to observe such a world; it was in the slum that I experienced freedom and independence for the first time. The way they talked about marriage, love and life made me realise that we too, can soar high in the open sky like a free bird. Realising this really changes a person – it is not as simple as just coming out of these institutions, but to comprehend that this is a continuous process and struggle. The pillars of organisation and order contain and stifle us, and it is up to us to free ourselves from the chains of these systems. I thought that even I can be free from the constraints of a domestic existence and live life on my own terms. I learned this from the woman I met, from the love I felt, and maybe, from the desires that were awakening within me.

I would like to talk about Bhanvari. I learned a lot from her. She was a 60 year old woman and I was working in Delhi at that time. When I used to visit slums, that 60 year old woman told me that there were two women and the love between them was very deep, you also call it “one soul and two bodies”. The relationship was that strong. As we started meeting more frequently, she also confessed that she was in a relationship with the woman her husband was seeing. When I heard her story, it just stunned me. I used to think that there should be some moral values, one man-one woman. To understand this kind of relationship was difficult for me, I was in a dilemma. Since I too was in a similar situation that challenged all my ideas of moral values and marriage, I learnt a lot from her. After being married for 10 years, I fell in love with a woman. In fact, I fell in love with two women at the same time. To keep love bound and locked within yourself is difficult. Even though I’ve had experiences and loved women in school, I didn’t know living this life could be a reality. Because in a middle class upbringing, you are constantly pressured about getting married and having children. For the first time in my comfortable middle class life, I found the space for being able to talk about and express love and sexual desire. Earlier I used to think that love is bound by age and marriage. I’d never had the opportunity to observe such a world; it was in the slum that I experienced freedom and independence for the first time. The way they talked about marriage, love and life made me realise that we too, can soar high in the open sky like a free bird. Realising this really changes a person – it is not as simple as just coming out of these institutions, but to comprehend that this is a continuous process and struggle. The pillars of organisation and order contain and stifle us, and it is up to us to free ourselves from the chains of these systems. I thought that even I can be free from the constraints of a domestic existence and live life on my own terms. I learned this from the woman I met, from the love I felt, and maybe, from the desires that were awakening within me. And is that what led you to write a book about lesbian love in unprivileged India, about the love between women from working class backgrounds, even though in different geographical locations?In my experiences, I never fit in properly in the norms of society. So, where can I find women like me whom I could speak to? It was my wish to meet more women who were just like me, or like Bhanvari. I wanted to know them and write about them. They shared their experiences with me and I shared my experiences with them and in this entire experience of sharing, I saw how it all affected us and changed us as well. Then I realised that love has no gender, caste, religion, village or city, it's something that touches all of us. There was no image of a book in my mind. I never thought I’d write a book. When I was working with these women, the terrible mental state I’d been in was getting better as I tried to connect these issues and I thought of writing on this subject. My heart wanted to write about the kind of people I met in the slums, who were facing the same difficulties that I was facing because of my sexuality, even though my problems were much smaller in comparison. Shivers ran down my spine and I thought that it’s important to talk about us in this way to give strength to the people who’re going through tough times because of the same problems. When you say ‘talk about us in this way’ what do you mean, and why?Earlier, in the women’s movement whenever we talked about our desires or lesbian love – we were told to talk about labour. The newspapers didn’t talk explicitly about lesbians, because of which people goaded us to show them which lesbian working class women were the ones we were helping, to justify our contention that queer love mattered politically. A similar thinking presided over the women’s movement that said that this issue is not on the priority list… I wish our lives were so neatly divided in boxes. But it is not how reality works. I remember when there were few groups that were campaigning for the film Fire (1996) as a film that stood for lesbian rights. It was a peak moment in our lives. After so many fights and getting told that we cannot put a poster with ‘Lesbian’ word on it (by other feminists), we were still on the streets. There was a poster that all of us treasured a lot which said – “LESBIANS ARE INDIANS" because that time they were saying that Indians can’t be lesbians. But during the campaign I also realised that we were too urban. Where Bhanwari and I were working it was a different space and situation. I wanted to break this silence around the popular assumptions about the supposed non-existence of lesbianism among working class women for many reasons.We still think that we need to remove poverty first, then we will come to pleasure. But isn’t it against human rights and desires to not have pleasure? To understand that our sexual desires and our poverty are not two dimensions, just like the hunger of stomach and hunger of womb, can bring us closer. When you talk about these two types of hunger, it reminds me of how striking the emotional and dramatic quality of the stories and conversations are. Even though this is a book in the domain of research and academia, what pulses through the stories are emotions. Why was this important to you? It’s simple, to live life emotions are very important so why should we suppress them?We are already so repressed!The conversations were very emotionally saturated and I was worried that something that was so affecting in Bhojpuri or Gujarati, would sound clumsy in English, to evokeI the same emotions in readers’ hearts that had been evoked in my heart. because they too were not able to comprehend their sexual desires openly, what their body needed. You know often we aren’t able to articulate exactly what we are feeling in our bodies, what our sexual desires are, so I wanted to find a way to bring out the emotion and meaning of these accounts.The beauty of stories is that they’re able to speak about life in the truest way, which politics cannot say. I also feel that when we are unable to say something, then we have to tell it through a story, because stories are a form of data - numbers feel awkward to me- and numbers are not the only kind of data.To describe the stories as ‘true stories’ there would be a falsity in having to say it like that - you know? Because, yes, although these are true stories, I shoudn’t need to use the word "true" to make them meaningful. They carry their own weight.

And is that what led you to write a book about lesbian love in unprivileged India, about the love between women from working class backgrounds, even though in different geographical locations?In my experiences, I never fit in properly in the norms of society. So, where can I find women like me whom I could speak to? It was my wish to meet more women who were just like me, or like Bhanvari. I wanted to know them and write about them. They shared their experiences with me and I shared my experiences with them and in this entire experience of sharing, I saw how it all affected us and changed us as well. Then I realised that love has no gender, caste, religion, village or city, it's something that touches all of us. There was no image of a book in my mind. I never thought I’d write a book. When I was working with these women, the terrible mental state I’d been in was getting better as I tried to connect these issues and I thought of writing on this subject. My heart wanted to write about the kind of people I met in the slums, who were facing the same difficulties that I was facing because of my sexuality, even though my problems were much smaller in comparison. Shivers ran down my spine and I thought that it’s important to talk about us in this way to give strength to the people who’re going through tough times because of the same problems. When you say ‘talk about us in this way’ what do you mean, and why?Earlier, in the women’s movement whenever we talked about our desires or lesbian love – we were told to talk about labour. The newspapers didn’t talk explicitly about lesbians, because of which people goaded us to show them which lesbian working class women were the ones we were helping, to justify our contention that queer love mattered politically. A similar thinking presided over the women’s movement that said that this issue is not on the priority list… I wish our lives were so neatly divided in boxes. But it is not how reality works. I remember when there were few groups that were campaigning for the film Fire (1996) as a film that stood for lesbian rights. It was a peak moment in our lives. After so many fights and getting told that we cannot put a poster with ‘Lesbian’ word on it (by other feminists), we were still on the streets. There was a poster that all of us treasured a lot which said – “LESBIANS ARE INDIANS" because that time they were saying that Indians can’t be lesbians. But during the campaign I also realised that we were too urban. Where Bhanwari and I were working it was a different space and situation. I wanted to break this silence around the popular assumptions about the supposed non-existence of lesbianism among working class women for many reasons.We still think that we need to remove poverty first, then we will come to pleasure. But isn’t it against human rights and desires to not have pleasure? To understand that our sexual desires and our poverty are not two dimensions, just like the hunger of stomach and hunger of womb, can bring us closer. When you talk about these two types of hunger, it reminds me of how striking the emotional and dramatic quality of the stories and conversations are. Even though this is a book in the domain of research and academia, what pulses through the stories are emotions. Why was this important to you? It’s simple, to live life emotions are very important so why should we suppress them?We are already so repressed!The conversations were very emotionally saturated and I was worried that something that was so affecting in Bhojpuri or Gujarati, would sound clumsy in English, to evokeI the same emotions in readers’ hearts that had been evoked in my heart. because they too were not able to comprehend their sexual desires openly, what their body needed. You know often we aren’t able to articulate exactly what we are feeling in our bodies, what our sexual desires are, so I wanted to find a way to bring out the emotion and meaning of these accounts.The beauty of stories is that they’re able to speak about life in the truest way, which politics cannot say. I also feel that when we are unable to say something, then we have to tell it through a story, because stories are a form of data - numbers feel awkward to me- and numbers are not the only kind of data.To describe the stories as ‘true stories’ there would be a falsity in having to say it like that - you know? Because, yes, although these are true stories, I shoudn’t need to use the word "true" to make them meaningful. They carry their own weight. In almost 80% of the stories, people didn’t use the word “lesbian” to describe their queer love though they were living that relationship intensely and sometimes openly and other people too acknowledged those relationships as romantic and sexual. What do you think of the existence of terms like “lesbian”? I too came from a small town. I heard the word lesbian for the first time when I moved to Delhi. And since then we have been using this word only. We didn’t use the Trans word that much. Language has also changed in the context of HIV/AIDS activism, but I am also afraid that this change in the use of language is categorising us into different compartments. As an activist, I know that terminology is necessary to be able to go to the state and have an identifiable front. If we talk about the Transgender Board, the governmental employees didn’t know anything about the trans community till the time a term or word and an image related to that word was presented to them; they didn’t have a clue about the same. That’s why the use of such terms, in my opinion, should be understood as a necessity for dealing with the state. That said, these terms don’t have much of a relation with real lives and how they’re lived, not according to me. I think that we as a culture turn more to gestures than words to express ourselves. So to some extent we don’t have a verbal vocabulary which we can easily use in legalistic contexts. But it doesn’t mean that a practice is not understood or even accepted. I also saw in rural areas how transmen are referred to as “bhai” or “babu” in common practice. The way of describing it is different. Terminology has its own problems too. It really restricts us and creates many boundaries in order to fit things in boxes, like how society tries to fit ‘men’ and ‘women’ in boxes. They can tie us down.At the end of my book, I wondered why people chase terms and the identities associated with them so much, when what we want is to escape the boundaries of identities, especially as we progress in the queer movement. We are maturing in this movement and are understanding that our identities are complicated, messy and can’t be contained within different limits. And well, I really like that it is this way. It is true to life. Queer love and secrecy have always had to go hand-in-hand. But your book surprises us in the way you talk about the freedom in the lives of the people you met, alongside the violence and oppression some of them experience. It’s an intriguing duality.It is natural that when we are in love with someone, we want to get intimate with them and spend our lives with them. So, there are many couples who run away from their homes and begin a new life in cities together. And If we look at our history, we would see that people especially who are assigned female at birth have remained anonymous, completely left out of the history that we read. We don’t talk about their love that fluently. But as queer couples they would have to live under the radar in general.So, people like us (queer) or those who live on the margins in some way, or belong to a backward group, they live a dual life. They retain a deep understanding of themselves and those who live in the society. They live like a chameleon, with a deep understanding of themselves as well as the other heteronormative world - to protect themselves, and also, to be themselves. Once we get this understanding, we mould ourselves in such a way that we become that person they want us to be, while being ourselves.But one thing I want to say, though I may sound politically incorrect - secrecy has its own fun. It is like an adventure. And I am not implying that we should not love openly, but we should also look at the pleasures, the thrills of loving in secret. I hope we don’t lose those adventures in love.

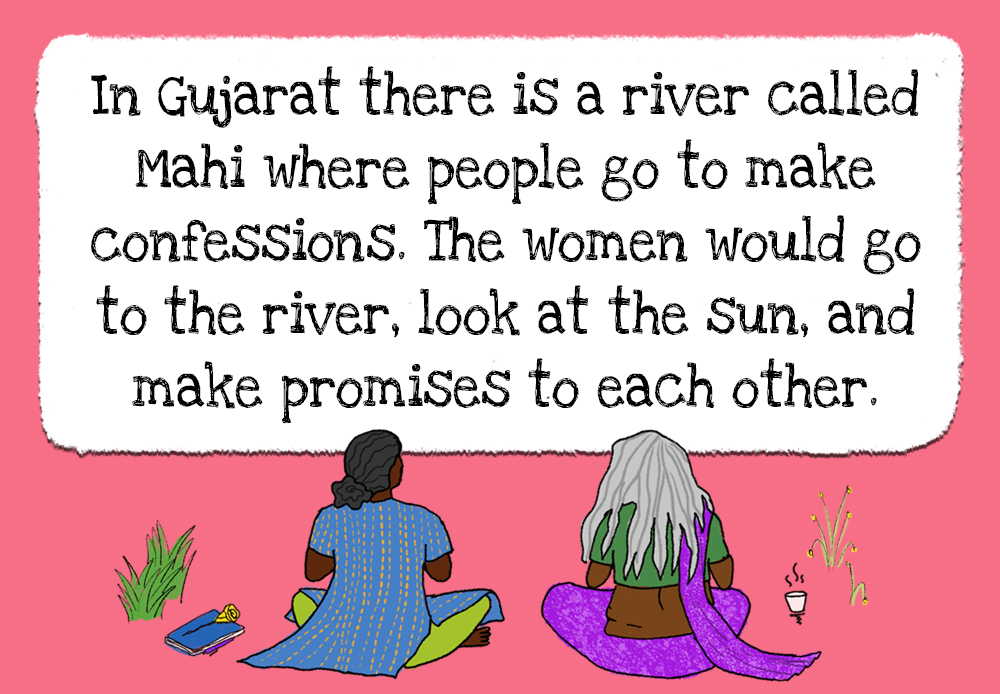

In almost 80% of the stories, people didn’t use the word “lesbian” to describe their queer love though they were living that relationship intensely and sometimes openly and other people too acknowledged those relationships as romantic and sexual. What do you think of the existence of terms like “lesbian”? I too came from a small town. I heard the word lesbian for the first time when I moved to Delhi. And since then we have been using this word only. We didn’t use the Trans word that much. Language has also changed in the context of HIV/AIDS activism, but I am also afraid that this change in the use of language is categorising us into different compartments. As an activist, I know that terminology is necessary to be able to go to the state and have an identifiable front. If we talk about the Transgender Board, the governmental employees didn’t know anything about the trans community till the time a term or word and an image related to that word was presented to them; they didn’t have a clue about the same. That’s why the use of such terms, in my opinion, should be understood as a necessity for dealing with the state. That said, these terms don’t have much of a relation with real lives and how they’re lived, not according to me. I think that we as a culture turn more to gestures than words to express ourselves. So to some extent we don’t have a verbal vocabulary which we can easily use in legalistic contexts. But it doesn’t mean that a practice is not understood or even accepted. I also saw in rural areas how transmen are referred to as “bhai” or “babu” in common practice. The way of describing it is different. Terminology has its own problems too. It really restricts us and creates many boundaries in order to fit things in boxes, like how society tries to fit ‘men’ and ‘women’ in boxes. They can tie us down.At the end of my book, I wondered why people chase terms and the identities associated with them so much, when what we want is to escape the boundaries of identities, especially as we progress in the queer movement. We are maturing in this movement and are understanding that our identities are complicated, messy and can’t be contained within different limits. And well, I really like that it is this way. It is true to life. Queer love and secrecy have always had to go hand-in-hand. But your book surprises us in the way you talk about the freedom in the lives of the people you met, alongside the violence and oppression some of them experience. It’s an intriguing duality.It is natural that when we are in love with someone, we want to get intimate with them and spend our lives with them. So, there are many couples who run away from their homes and begin a new life in cities together. And If we look at our history, we would see that people especially who are assigned female at birth have remained anonymous, completely left out of the history that we read. We don’t talk about their love that fluently. But as queer couples they would have to live under the radar in general.So, people like us (queer) or those who live on the margins in some way, or belong to a backward group, they live a dual life. They retain a deep understanding of themselves and those who live in the society. They live like a chameleon, with a deep understanding of themselves as well as the other heteronormative world - to protect themselves, and also, to be themselves. Once we get this understanding, we mould ourselves in such a way that we become that person they want us to be, while being ourselves.But one thing I want to say, though I may sound politically incorrect - secrecy has its own fun. It is like an adventure. And I am not implying that we should not love openly, but we should also look at the pleasures, the thrills of loving in secret. I hope we don’t lose those adventures in love.  Do you think rights to marriage could resolve some of these dualities? The thing about marriage is that it is a very complex system which is related to caste. It is tied to property, children, etc., so there are many factors that make marriage a very strong part of society. But it is necessary to talk about because many people are just forced into marrying which is why it is important to understand the inequalities in the system of marriage. But in life around us, there are many things that challenge marriage. Even in villages, there are many houses which are headed by women. Many Muslim and Dalit women don’t consider marriage religious and if they want to, they leave their husbands. Their views about marriage are very practical. They’ve left their marriages, or stayed with their husbands but maintained their relationships outside of marriage. I think if as a queer couple we are also asking for marriage rights, we also have to conceptualise marriage in a different way. How can we reconceptualise these relationships like marriage in a queer sense?When we fall in love with someone, we may want to celebrate the passion and love, and find a way to keep faith in each other. Women have created this space of possibilities by performing popular rituals in different cultures. For example, in Gujarat there is a river called Mahi where people would go and make confessions or you know speak a truth. Quite often, the women I have worked with, they would go to the river, look at the sun, and make promises to each other. And many years ago, Bhanwari too stood in that river and made such promises with her friends. As I said, we as a culture use more gestures and metaphors than words. I tried to find what it means when we say “I Love You” to someone and I asked different people too. We are more aural than verbal, often our way of expressing that love is through cooking or remembering the things our loved ones like. When you eat someone’s cooking, is this love for food, or for something else? This is what I have tried to find out in these stories - the different ways we express our love. We express ourselves by the pouring of the clouds, we’ll arrange the dining table beautifully...so I think there is a certain sense of excitement and romance in this silence as well.I think the meaning of sexual is quite varied for different people. Like Bhawri says she’d never been touched the way she’d been touched by these hardworking and proud hands, and talks about what she experienced in work and comradeship...what would we call that? That’s when I realized the definition of sexual is very diverse and it’s in our every being. To restrict this to the bedroom or just to our bodies, our genitals, is also a problem. It feels like you are a feminist and activist who loves talking about love. So what is love in your definition? And how can we open up to love? I think love is like water, it can take any form, but it is difficult to mould it into something like marriage, treasure it or contain it into something. That’s why, for people like us, who live on the margins, it is difficult to live everyday life without any struggles. Love, it is like a storm collapsed into a fold or the entire sky reflected in a tiny drop.Love has no road map to follow. You just have to really listen to each other.

Do you think rights to marriage could resolve some of these dualities? The thing about marriage is that it is a very complex system which is related to caste. It is tied to property, children, etc., so there are many factors that make marriage a very strong part of society. But it is necessary to talk about because many people are just forced into marrying which is why it is important to understand the inequalities in the system of marriage. But in life around us, there are many things that challenge marriage. Even in villages, there are many houses which are headed by women. Many Muslim and Dalit women don’t consider marriage religious and if they want to, they leave their husbands. Their views about marriage are very practical. They’ve left their marriages, or stayed with their husbands but maintained their relationships outside of marriage. I think if as a queer couple we are also asking for marriage rights, we also have to conceptualise marriage in a different way. How can we reconceptualise these relationships like marriage in a queer sense?When we fall in love with someone, we may want to celebrate the passion and love, and find a way to keep faith in each other. Women have created this space of possibilities by performing popular rituals in different cultures. For example, in Gujarat there is a river called Mahi where people would go and make confessions or you know speak a truth. Quite often, the women I have worked with, they would go to the river, look at the sun, and make promises to each other. And many years ago, Bhanwari too stood in that river and made such promises with her friends. As I said, we as a culture use more gestures and metaphors than words. I tried to find what it means when we say “I Love You” to someone and I asked different people too. We are more aural than verbal, often our way of expressing that love is through cooking or remembering the things our loved ones like. When you eat someone’s cooking, is this love for food, or for something else? This is what I have tried to find out in these stories - the different ways we express our love. We express ourselves by the pouring of the clouds, we’ll arrange the dining table beautifully...so I think there is a certain sense of excitement and romance in this silence as well.I think the meaning of sexual is quite varied for different people. Like Bhawri says she’d never been touched the way she’d been touched by these hardworking and proud hands, and talks about what she experienced in work and comradeship...what would we call that? That’s when I realized the definition of sexual is very diverse and it’s in our every being. To restrict this to the bedroom or just to our bodies, our genitals, is also a problem. It feels like you are a feminist and activist who loves talking about love. So what is love in your definition? And how can we open up to love? I think love is like water, it can take any form, but it is difficult to mould it into something like marriage, treasure it or contain it into something. That’s why, for people like us, who live on the margins, it is difficult to live everyday life without any struggles. Love, it is like a storm collapsed into a fold or the entire sky reflected in a tiny drop.Love has no road map to follow. You just have to really listen to each other.

Score:

0/

Maya Sharma is a feminist and queer activist who is a part of the Indian Women’s Movement. She was born in Rajasthan and went on to study literature in Delhi. Her life changed radically when she came in contact with the Indian Women’s Movement and activism. She chose to leave her domestic life as a housewife in an urban middle class home and become an activist. It was the work she did here with people from Delhi’s resettlement colonies and working class women across India that brought the paper and pen together for her. She has co-authored a book on Single Women in Hindi and a path-breaking piece of work “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India” published in 2006. This book was a collection of ten stories of working class queer women, following their stories and their unique voices. The book is a unique work that brings together story and research, to show us a glimpse of the world of women loving women in working class India - and through it also opened up a multi-layered meditation on life, love and feminism for all of us. Currently, she is working with LBT community in Vikalp (Women’s Group) Vadodara. This interview is based on two conversations at different times that we, at Agents of Ishq, had with Maya Sharma. They have been lightly edited for clarity. What was your journey of becoming an activist, and then to having the conversations about sexuality, identity and gender that led to your book, “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged in India”? The best thing I discovered when I began working in the bastis and resettlement colonies, while talking to the women there is that they, who live so-called “non-political lives”, are able to talk about their lives the exact way in which they’re living them. We are not not able to speak in the same way, with the same simplicity. Maybe we have studied too much because of which our lives have moved far away from the real thing. Our lives are filled with impressing people, dressing up, going out… But there is a difference between the way in which these women get ready and we get ready. The women in the slum used to say that there are two kinds of hunger, one of the womb and the other of the stomach (ek kok ki bhook, ek pet ke bhook). When they say womb, it is expressive of sensualness, sexual desire. That’s why they’re so in touch with their lives and feelings. This realisation was so unique and important for me and it helped me in knowing many unknown things and learning a lot from them.

Maya Sharma is a feminist and queer activist who is a part of the Indian Women’s Movement. She was born in Rajasthan and went on to study literature in Delhi. Her life changed radically when she came in contact with the Indian Women’s Movement and activism. She chose to leave her domestic life as a housewife in an urban middle class home and become an activist. It was the work she did here with people from Delhi’s resettlement colonies and working class women across India that brought the paper and pen together for her. She has co-authored a book on Single Women in Hindi and a path-breaking piece of work “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged India” published in 2006. This book was a collection of ten stories of working class queer women, following their stories and their unique voices. The book is a unique work that brings together story and research, to show us a glimpse of the world of women loving women in working class India - and through it also opened up a multi-layered meditation on life, love and feminism for all of us. Currently, she is working with LBT community in Vikalp (Women’s Group) Vadodara. This interview is based on two conversations at different times that we, at Agents of Ishq, had with Maya Sharma. They have been lightly edited for clarity. What was your journey of becoming an activist, and then to having the conversations about sexuality, identity and gender that led to your book, “Loving Women: Being Lesbian in Unprivileged in India”? The best thing I discovered when I began working in the bastis and resettlement colonies, while talking to the women there is that they, who live so-called “non-political lives”, are able to talk about their lives the exact way in which they’re living them. We are not not able to speak in the same way, with the same simplicity. Maybe we have studied too much because of which our lives have moved far away from the real thing. Our lives are filled with impressing people, dressing up, going out… But there is a difference between the way in which these women get ready and we get ready. The women in the slum used to say that there are two kinds of hunger, one of the womb and the other of the stomach (ek kok ki bhook, ek pet ke bhook). When they say womb, it is expressive of sensualness, sexual desire. That’s why they’re so in touch with their lives and feelings. This realisation was so unique and important for me and it helped me in knowing many unknown things and learning a lot from them. I would like to talk about Bhanvari. I learned a lot from her. She was a 60 year old woman and I was working in Delhi at that time. When I used to visit slums, that 60 year old woman told me that there were two women and the love between them was very deep, you also call it “one soul and two bodies”. The relationship was that strong. As we started meeting more frequently, she also confessed that she was in a relationship with the woman her husband was seeing. When I heard her story, it just stunned me. I used to think that there should be some moral values, one man-one woman. To understand this kind of relationship was difficult for me, I was in a dilemma. Since I too was in a similar situation that challenged all my ideas of moral values and marriage, I learnt a lot from her. After being married for 10 years, I fell in love with a woman. In fact, I fell in love with two women at the same time. To keep love bound and locked within yourself is difficult. Even though I’ve had experiences and loved women in school, I didn’t know living this life could be a reality. Because in a middle class upbringing, you are constantly pressured about getting married and having children. For the first time in my comfortable middle class life, I found the space for being able to talk about and express love and sexual desire. Earlier I used to think that love is bound by age and marriage. I’d never had the opportunity to observe such a world; it was in the slum that I experienced freedom and independence for the first time. The way they talked about marriage, love and life made me realise that we too, can soar high in the open sky like a free bird. Realising this really changes a person – it is not as simple as just coming out of these institutions, but to comprehend that this is a continuous process and struggle. The pillars of organisation and order contain and stifle us, and it is up to us to free ourselves from the chains of these systems. I thought that even I can be free from the constraints of a domestic existence and live life on my own terms. I learned this from the woman I met, from the love I felt, and maybe, from the desires that were awakening within me.

I would like to talk about Bhanvari. I learned a lot from her. She was a 60 year old woman and I was working in Delhi at that time. When I used to visit slums, that 60 year old woman told me that there were two women and the love between them was very deep, you also call it “one soul and two bodies”. The relationship was that strong. As we started meeting more frequently, she also confessed that she was in a relationship with the woman her husband was seeing. When I heard her story, it just stunned me. I used to think that there should be some moral values, one man-one woman. To understand this kind of relationship was difficult for me, I was in a dilemma. Since I too was in a similar situation that challenged all my ideas of moral values and marriage, I learnt a lot from her. After being married for 10 years, I fell in love with a woman. In fact, I fell in love with two women at the same time. To keep love bound and locked within yourself is difficult. Even though I’ve had experiences and loved women in school, I didn’t know living this life could be a reality. Because in a middle class upbringing, you are constantly pressured about getting married and having children. For the first time in my comfortable middle class life, I found the space for being able to talk about and express love and sexual desire. Earlier I used to think that love is bound by age and marriage. I’d never had the opportunity to observe such a world; it was in the slum that I experienced freedom and independence for the first time. The way they talked about marriage, love and life made me realise that we too, can soar high in the open sky like a free bird. Realising this really changes a person – it is not as simple as just coming out of these institutions, but to comprehend that this is a continuous process and struggle. The pillars of organisation and order contain and stifle us, and it is up to us to free ourselves from the chains of these systems. I thought that even I can be free from the constraints of a domestic existence and live life on my own terms. I learned this from the woman I met, from the love I felt, and maybe, from the desires that were awakening within me. And is that what led you to write a book about lesbian love in unprivileged India, about the love between women from working class backgrounds, even though in different geographical locations?In my experiences, I never fit in properly in the norms of society. So, where can I find women like me whom I could speak to? It was my wish to meet more women who were just like me, or like Bhanvari. I wanted to know them and write about them. They shared their experiences with me and I shared my experiences with them and in this entire experience of sharing, I saw how it all affected us and changed us as well. Then I realised that love has no gender, caste, religion, village or city, it's something that touches all of us. There was no image of a book in my mind. I never thought I’d write a book. When I was working with these women, the terrible mental state I’d been in was getting better as I tried to connect these issues and I thought of writing on this subject. My heart wanted to write about the kind of people I met in the slums, who were facing the same difficulties that I was facing because of my sexuality, even though my problems were much smaller in comparison. Shivers ran down my spine and I thought that it’s important to talk about us in this way to give strength to the people who’re going through tough times because of the same problems. When you say ‘talk about us in this way’ what do you mean, and why?Earlier, in the women’s movement whenever we talked about our desires or lesbian love – we were told to talk about labour. The newspapers didn’t talk explicitly about lesbians, because of which people goaded us to show them which lesbian working class women were the ones we were helping, to justify our contention that queer love mattered politically. A similar thinking presided over the women’s movement that said that this issue is not on the priority list… I wish our lives were so neatly divided in boxes. But it is not how reality works. I remember when there were few groups that were campaigning for the film Fire (1996) as a film that stood for lesbian rights. It was a peak moment in our lives. After so many fights and getting told that we cannot put a poster with ‘Lesbian’ word on it (by other feminists), we were still on the streets. There was a poster that all of us treasured a lot which said – “LESBIANS ARE INDIANS" because that time they were saying that Indians can’t be lesbians. But during the campaign I also realised that we were too urban. Where Bhanwari and I were working it was a different space and situation. I wanted to break this silence around the popular assumptions about the supposed non-existence of lesbianism among working class women for many reasons.We still think that we need to remove poverty first, then we will come to pleasure. But isn’t it against human rights and desires to not have pleasure? To understand that our sexual desires and our poverty are not two dimensions, just like the hunger of stomach and hunger of womb, can bring us closer. When you talk about these two types of hunger, it reminds me of how striking the emotional and dramatic quality of the stories and conversations are. Even though this is a book in the domain of research and academia, what pulses through the stories are emotions. Why was this important to you? It’s simple, to live life emotions are very important so why should we suppress them?We are already so repressed!The conversations were very emotionally saturated and I was worried that something that was so affecting in Bhojpuri or Gujarati, would sound clumsy in English, to evokeI the same emotions in readers’ hearts that had been evoked in my heart. because they too were not able to comprehend their sexual desires openly, what their body needed. You know often we aren’t able to articulate exactly what we are feeling in our bodies, what our sexual desires are, so I wanted to find a way to bring out the emotion and meaning of these accounts.The beauty of stories is that they’re able to speak about life in the truest way, which politics cannot say. I also feel that when we are unable to say something, then we have to tell it through a story, because stories are a form of data - numbers feel awkward to me- and numbers are not the only kind of data.To describe the stories as ‘true stories’ there would be a falsity in having to say it like that - you know? Because, yes, although these are true stories, I shoudn’t need to use the word "true" to make them meaningful. They carry their own weight.

And is that what led you to write a book about lesbian love in unprivileged India, about the love between women from working class backgrounds, even though in different geographical locations?In my experiences, I never fit in properly in the norms of society. So, where can I find women like me whom I could speak to? It was my wish to meet more women who were just like me, or like Bhanvari. I wanted to know them and write about them. They shared their experiences with me and I shared my experiences with them and in this entire experience of sharing, I saw how it all affected us and changed us as well. Then I realised that love has no gender, caste, religion, village or city, it's something that touches all of us. There was no image of a book in my mind. I never thought I’d write a book. When I was working with these women, the terrible mental state I’d been in was getting better as I tried to connect these issues and I thought of writing on this subject. My heart wanted to write about the kind of people I met in the slums, who were facing the same difficulties that I was facing because of my sexuality, even though my problems were much smaller in comparison. Shivers ran down my spine and I thought that it’s important to talk about us in this way to give strength to the people who’re going through tough times because of the same problems. When you say ‘talk about us in this way’ what do you mean, and why?Earlier, in the women’s movement whenever we talked about our desires or lesbian love – we were told to talk about labour. The newspapers didn’t talk explicitly about lesbians, because of which people goaded us to show them which lesbian working class women were the ones we were helping, to justify our contention that queer love mattered politically. A similar thinking presided over the women’s movement that said that this issue is not on the priority list… I wish our lives were so neatly divided in boxes. But it is not how reality works. I remember when there were few groups that were campaigning for the film Fire (1996) as a film that stood for lesbian rights. It was a peak moment in our lives. After so many fights and getting told that we cannot put a poster with ‘Lesbian’ word on it (by other feminists), we were still on the streets. There was a poster that all of us treasured a lot which said – “LESBIANS ARE INDIANS" because that time they were saying that Indians can’t be lesbians. But during the campaign I also realised that we were too urban. Where Bhanwari and I were working it was a different space and situation. I wanted to break this silence around the popular assumptions about the supposed non-existence of lesbianism among working class women for many reasons.We still think that we need to remove poverty first, then we will come to pleasure. But isn’t it against human rights and desires to not have pleasure? To understand that our sexual desires and our poverty are not two dimensions, just like the hunger of stomach and hunger of womb, can bring us closer. When you talk about these two types of hunger, it reminds me of how striking the emotional and dramatic quality of the stories and conversations are. Even though this is a book in the domain of research and academia, what pulses through the stories are emotions. Why was this important to you? It’s simple, to live life emotions are very important so why should we suppress them?We are already so repressed!The conversations were very emotionally saturated and I was worried that something that was so affecting in Bhojpuri or Gujarati, would sound clumsy in English, to evokeI the same emotions in readers’ hearts that had been evoked in my heart. because they too were not able to comprehend their sexual desires openly, what their body needed. You know often we aren’t able to articulate exactly what we are feeling in our bodies, what our sexual desires are, so I wanted to find a way to bring out the emotion and meaning of these accounts.The beauty of stories is that they’re able to speak about life in the truest way, which politics cannot say. I also feel that when we are unable to say something, then we have to tell it through a story, because stories are a form of data - numbers feel awkward to me- and numbers are not the only kind of data.To describe the stories as ‘true stories’ there would be a falsity in having to say it like that - you know? Because, yes, although these are true stories, I shoudn’t need to use the word "true" to make them meaningful. They carry their own weight. In almost 80% of the stories, people didn’t use the word “lesbian” to describe their queer love though they were living that relationship intensely and sometimes openly and other people too acknowledged those relationships as romantic and sexual. What do you think of the existence of terms like “lesbian”? I too came from a small town. I heard the word lesbian for the first time when I moved to Delhi. And since then we have been using this word only. We didn’t use the Trans word that much. Language has also changed in the context of HIV/AIDS activism, but I am also afraid that this change in the use of language is categorising us into different compartments. As an activist, I know that terminology is necessary to be able to go to the state and have an identifiable front. If we talk about the Transgender Board, the governmental employees didn’t know anything about the trans community till the time a term or word and an image related to that word was presented to them; they didn’t have a clue about the same. That’s why the use of such terms, in my opinion, should be understood as a necessity for dealing with the state. That said, these terms don’t have much of a relation with real lives and how they’re lived, not according to me. I think that we as a culture turn more to gestures than words to express ourselves. So to some extent we don’t have a verbal vocabulary which we can easily use in legalistic contexts. But it doesn’t mean that a practice is not understood or even accepted. I also saw in rural areas how transmen are referred to as “bhai” or “babu” in common practice. The way of describing it is different. Terminology has its own problems too. It really restricts us and creates many boundaries in order to fit things in boxes, like how society tries to fit ‘men’ and ‘women’ in boxes. They can tie us down.At the end of my book, I wondered why people chase terms and the identities associated with them so much, when what we want is to escape the boundaries of identities, especially as we progress in the queer movement. We are maturing in this movement and are understanding that our identities are complicated, messy and can’t be contained within different limits. And well, I really like that it is this way. It is true to life. Queer love and secrecy have always had to go hand-in-hand. But your book surprises us in the way you talk about the freedom in the lives of the people you met, alongside the violence and oppression some of them experience. It’s an intriguing duality.It is natural that when we are in love with someone, we want to get intimate with them and spend our lives with them. So, there are many couples who run away from their homes and begin a new life in cities together. And If we look at our history, we would see that people especially who are assigned female at birth have remained anonymous, completely left out of the history that we read. We don’t talk about their love that fluently. But as queer couples they would have to live under the radar in general.So, people like us (queer) or those who live on the margins in some way, or belong to a backward group, they live a dual life. They retain a deep understanding of themselves and those who live in the society. They live like a chameleon, with a deep understanding of themselves as well as the other heteronormative world - to protect themselves, and also, to be themselves. Once we get this understanding, we mould ourselves in such a way that we become that person they want us to be, while being ourselves.But one thing I want to say, though I may sound politically incorrect - secrecy has its own fun. It is like an adventure. And I am not implying that we should not love openly, but we should also look at the pleasures, the thrills of loving in secret. I hope we don’t lose those adventures in love.

In almost 80% of the stories, people didn’t use the word “lesbian” to describe their queer love though they were living that relationship intensely and sometimes openly and other people too acknowledged those relationships as romantic and sexual. What do you think of the existence of terms like “lesbian”? I too came from a small town. I heard the word lesbian for the first time when I moved to Delhi. And since then we have been using this word only. We didn’t use the Trans word that much. Language has also changed in the context of HIV/AIDS activism, but I am also afraid that this change in the use of language is categorising us into different compartments. As an activist, I know that terminology is necessary to be able to go to the state and have an identifiable front. If we talk about the Transgender Board, the governmental employees didn’t know anything about the trans community till the time a term or word and an image related to that word was presented to them; they didn’t have a clue about the same. That’s why the use of such terms, in my opinion, should be understood as a necessity for dealing with the state. That said, these terms don’t have much of a relation with real lives and how they’re lived, not according to me. I think that we as a culture turn more to gestures than words to express ourselves. So to some extent we don’t have a verbal vocabulary which we can easily use in legalistic contexts. But it doesn’t mean that a practice is not understood or even accepted. I also saw in rural areas how transmen are referred to as “bhai” or “babu” in common practice. The way of describing it is different. Terminology has its own problems too. It really restricts us and creates many boundaries in order to fit things in boxes, like how society tries to fit ‘men’ and ‘women’ in boxes. They can tie us down.At the end of my book, I wondered why people chase terms and the identities associated with them so much, when what we want is to escape the boundaries of identities, especially as we progress in the queer movement. We are maturing in this movement and are understanding that our identities are complicated, messy and can’t be contained within different limits. And well, I really like that it is this way. It is true to life. Queer love and secrecy have always had to go hand-in-hand. But your book surprises us in the way you talk about the freedom in the lives of the people you met, alongside the violence and oppression some of them experience. It’s an intriguing duality.It is natural that when we are in love with someone, we want to get intimate with them and spend our lives with them. So, there are many couples who run away from their homes and begin a new life in cities together. And If we look at our history, we would see that people especially who are assigned female at birth have remained anonymous, completely left out of the history that we read. We don’t talk about their love that fluently. But as queer couples they would have to live under the radar in general.So, people like us (queer) or those who live on the margins in some way, or belong to a backward group, they live a dual life. They retain a deep understanding of themselves and those who live in the society. They live like a chameleon, with a deep understanding of themselves as well as the other heteronormative world - to protect themselves, and also, to be themselves. Once we get this understanding, we mould ourselves in such a way that we become that person they want us to be, while being ourselves.But one thing I want to say, though I may sound politically incorrect - secrecy has its own fun. It is like an adventure. And I am not implying that we should not love openly, but we should also look at the pleasures, the thrills of loving in secret. I hope we don’t lose those adventures in love.  Do you think rights to marriage could resolve some of these dualities? The thing about marriage is that it is a very complex system which is related to caste. It is tied to property, children, etc., so there are many factors that make marriage a very strong part of society. But it is necessary to talk about because many people are just forced into marrying which is why it is important to understand the inequalities in the system of marriage. But in life around us, there are many things that challenge marriage. Even in villages, there are many houses which are headed by women. Many Muslim and Dalit women don’t consider marriage religious and if they want to, they leave their husbands. Their views about marriage are very practical. They’ve left their marriages, or stayed with their husbands but maintained their relationships outside of marriage. I think if as a queer couple we are also asking for marriage rights, we also have to conceptualise marriage in a different way. How can we reconceptualise these relationships like marriage in a queer sense?When we fall in love with someone, we may want to celebrate the passion and love, and find a way to keep faith in each other. Women have created this space of possibilities by performing popular rituals in different cultures. For example, in Gujarat there is a river called Mahi where people would go and make confessions or you know speak a truth. Quite often, the women I have worked with, they would go to the river, look at the sun, and make promises to each other. And many years ago, Bhanwari too stood in that river and made such promises with her friends. As I said, we as a culture use more gestures and metaphors than words. I tried to find what it means when we say “I Love You” to someone and I asked different people too. We are more aural than verbal, often our way of expressing that love is through cooking or remembering the things our loved ones like. When you eat someone’s cooking, is this love for food, or for something else? This is what I have tried to find out in these stories - the different ways we express our love. We express ourselves by the pouring of the clouds, we’ll arrange the dining table beautifully...so I think there is a certain sense of excitement and romance in this silence as well.I think the meaning of sexual is quite varied for different people. Like Bhawri says she’d never been touched the way she’d been touched by these hardworking and proud hands, and talks about what she experienced in work and comradeship...what would we call that? That’s when I realized the definition of sexual is very diverse and it’s in our every being. To restrict this to the bedroom or just to our bodies, our genitals, is also a problem. It feels like you are a feminist and activist who loves talking about love. So what is love in your definition? And how can we open up to love? I think love is like water, it can take any form, but it is difficult to mould it into something like marriage, treasure it or contain it into something. That’s why, for people like us, who live on the margins, it is difficult to live everyday life without any struggles. Love, it is like a storm collapsed into a fold or the entire sky reflected in a tiny drop.Love has no road map to follow. You just have to really listen to each other.

Do you think rights to marriage could resolve some of these dualities? The thing about marriage is that it is a very complex system which is related to caste. It is tied to property, children, etc., so there are many factors that make marriage a very strong part of society. But it is necessary to talk about because many people are just forced into marrying which is why it is important to understand the inequalities in the system of marriage. But in life around us, there are many things that challenge marriage. Even in villages, there are many houses which are headed by women. Many Muslim and Dalit women don’t consider marriage religious and if they want to, they leave their husbands. Their views about marriage are very practical. They’ve left their marriages, or stayed with their husbands but maintained their relationships outside of marriage. I think if as a queer couple we are also asking for marriage rights, we also have to conceptualise marriage in a different way. How can we reconceptualise these relationships like marriage in a queer sense?When we fall in love with someone, we may want to celebrate the passion and love, and find a way to keep faith in each other. Women have created this space of possibilities by performing popular rituals in different cultures. For example, in Gujarat there is a river called Mahi where people would go and make confessions or you know speak a truth. Quite often, the women I have worked with, they would go to the river, look at the sun, and make promises to each other. And many years ago, Bhanwari too stood in that river and made such promises with her friends. As I said, we as a culture use more gestures and metaphors than words. I tried to find what it means when we say “I Love You” to someone and I asked different people too. We are more aural than verbal, often our way of expressing that love is through cooking or remembering the things our loved ones like. When you eat someone’s cooking, is this love for food, or for something else? This is what I have tried to find out in these stories - the different ways we express our love. We express ourselves by the pouring of the clouds, we’ll arrange the dining table beautifully...so I think there is a certain sense of excitement and romance in this silence as well.I think the meaning of sexual is quite varied for different people. Like Bhawri says she’d never been touched the way she’d been touched by these hardworking and proud hands, and talks about what she experienced in work and comradeship...what would we call that? That’s when I realized the definition of sexual is very diverse and it’s in our every being. To restrict this to the bedroom or just to our bodies, our genitals, is also a problem. It feels like you are a feminist and activist who loves talking about love. So what is love in your definition? And how can we open up to love? I think love is like water, it can take any form, but it is difficult to mould it into something like marriage, treasure it or contain it into something. That’s why, for people like us, who live on the margins, it is difficult to live everyday life without any struggles. Love, it is like a storm collapsed into a fold or the entire sky reflected in a tiny drop.Love has no road map to follow. You just have to really listen to each other.