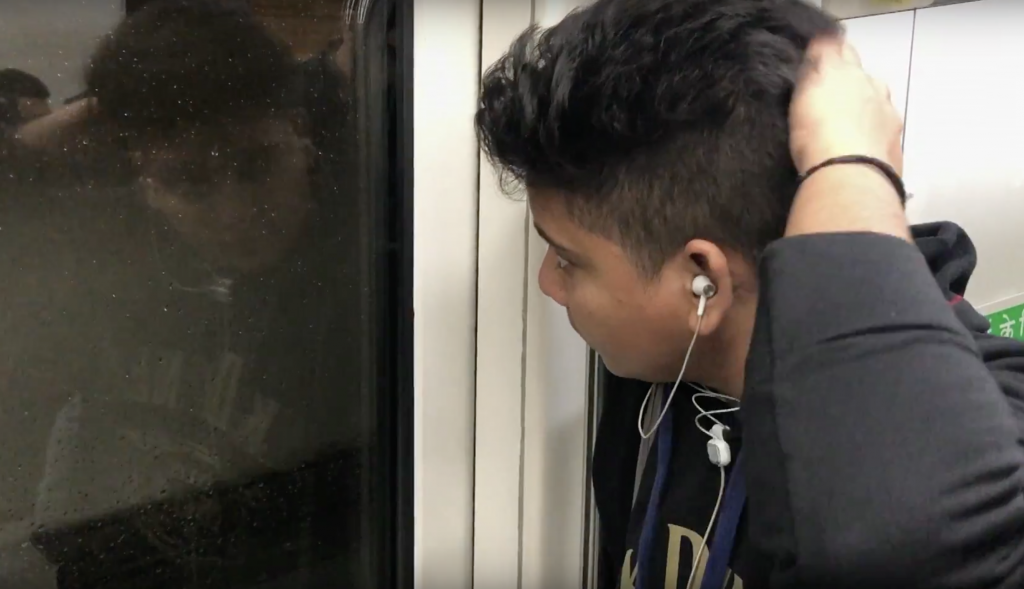

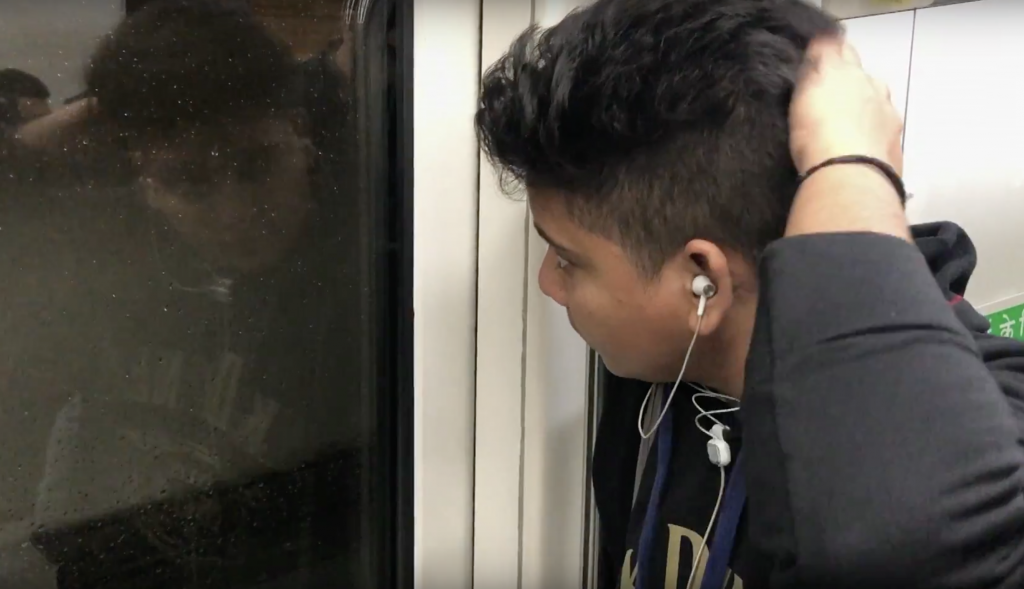

Please Mind the Gap is a short film about Anshuman, a young trans man in Delhi. We see him travel on the metro, navigating public space and constantly in transit alongside a rush of fellow passengers, while he tells us anecdotes from his life – his arrival in Delhi, the people he encounters on the metro, the instinctive gap he creates between himself and other men and women on the metro to avoid their prying, taking girls out for bike rides, and more. Delivered with warmth and humour, the film is a lovely portrait of it sparkling protagonist finding his way in the world, and will be shown this week at the Open Frame Film Festival in Delhi at 4:15 pm on September 16.We spoke to filmmakers Mitali Trivedi, a 26-year-old research scholar, and Gagandeep Singh, a 27-year-old lawyer, about their first-ever film.What was the starting point of the film? Did you set out to make a film about gender and sexuality, or did you set out to make a film about your protagonist, Anshuman?G: I had always been thinking about working on sexuality through arts, maybe in the form of a play or a movie. Mitali and I knew each other because we studied in the same university. I got in touch because I wanted to make a short film about cross dressing. We filled up a proposal for PSBT and that’s how we got to make our first movie.M: Our proposal looked really different from what the movie is all about now. We actually wanted to work on a film about public displays of affection by queer people on the Delhi Metro. Since the proposal was originally for a 10-minute film, we thought we would focus on people holding hands. We started hanging out with friends, had conversations about it, and in that process of exploring and getting to know folks and hearing their stories, we met Anshuman. And Anshuman used to introduce us to other people. One day while we were sitting and thinking about the film, we thought, why can’t we work with Anshuman, because he’s a great storyteller. Did this change in plan come about right at the research stage?G: Yes. Delhi is a place where many people migrate to because of their sexuality – the queer movement is very strong in Delhi. Right at the beginning we were told that because we were outsiders, and not from the queer community, we would have to make sure we did a lot of research – we couldn’t make any mistakes. That was great advice and it helped us a lot. We did a lot of research and didn’t just rely on our immediate circle of friends. At first, we didn’t meet Anshuman as the person we would work with so closely – he was initially introducing us to other people for our research because he worked with rights organisations.M: And also while researching, Anshuman was very forthcoming and eventually we became friends with him. So the process became easier because we would hang out with him all the time, and it became very natural for us to work with him.What about Anshuman drew you to him for this film?M: He was so forthcoming, he would always ensure that we were comfortable, if there was a serious moment he would crack a joke to lighten the mood – it was really beautiful. It felt like we were caring for him and he was caring for us. It became a relationship that was beyond this project. G: The film starts with the opening of a new metro line – he was the one who said, listen, there’s a new line opening, aaj chalte hain. He would give us suggestions and ideas.This film is largely about gender and sexuality, but it is not a narrow look at it by any means – when we see Anshuman, being trans might be a large facet of his identity, but it is still only one facet of many. We’re introduced to a charming, lovable person navigating a city, navigating identity, and navigating pleasure. Was that always the plan?M: As first-time filmmakers, we got a lot of advice from PSBT, and were encouraged to look at whatever we were making a film about as a whole. That was very ingrained in us – that we shouldn’t objectify the people we are working with for the film. Also, just given the kind of person Anshuman is, and the kind of bond we have with him, we couldn’t look at him just for his gender identity. We became friends, and you don’t see your friends as only one thing, right? So it happened naturally too.The entire film is shot on the Delhi metro, with Anshuman travelling up and down on its lines, talking about his life and interactions with other people on the metro. Why did you choose to focus on the metro?M: Because it’s a place in which I spend at least one-fourth of my day. It’s a space that feels so interesting – you get to see so much, and learn so much about other people, so I had always wanted to work on something related to the metro.

Did this change in plan come about right at the research stage?G: Yes. Delhi is a place where many people migrate to because of their sexuality – the queer movement is very strong in Delhi. Right at the beginning we were told that because we were outsiders, and not from the queer community, we would have to make sure we did a lot of research – we couldn’t make any mistakes. That was great advice and it helped us a lot. We did a lot of research and didn’t just rely on our immediate circle of friends. At first, we didn’t meet Anshuman as the person we would work with so closely – he was initially introducing us to other people for our research because he worked with rights organisations.M: And also while researching, Anshuman was very forthcoming and eventually we became friends with him. So the process became easier because we would hang out with him all the time, and it became very natural for us to work with him.What about Anshuman drew you to him for this film?M: He was so forthcoming, he would always ensure that we were comfortable, if there was a serious moment he would crack a joke to lighten the mood – it was really beautiful. It felt like we were caring for him and he was caring for us. It became a relationship that was beyond this project. G: The film starts with the opening of a new metro line – he was the one who said, listen, there’s a new line opening, aaj chalte hain. He would give us suggestions and ideas.This film is largely about gender and sexuality, but it is not a narrow look at it by any means – when we see Anshuman, being trans might be a large facet of his identity, but it is still only one facet of many. We’re introduced to a charming, lovable person navigating a city, navigating identity, and navigating pleasure. Was that always the plan?M: As first-time filmmakers, we got a lot of advice from PSBT, and were encouraged to look at whatever we were making a film about as a whole. That was very ingrained in us – that we shouldn’t objectify the people we are working with for the film. Also, just given the kind of person Anshuman is, and the kind of bond we have with him, we couldn’t look at him just for his gender identity. We became friends, and you don’t see your friends as only one thing, right? So it happened naturally too.The entire film is shot on the Delhi metro, with Anshuman travelling up and down on its lines, talking about his life and interactions with other people on the metro. Why did you choose to focus on the metro?M: Because it’s a place in which I spend at least one-fourth of my day. It’s a space that feels so interesting – you get to see so much, and learn so much about other people, so I had always wanted to work on something related to the metro. In your film, you include metro announcements, in which you have these very bland authoritative male and female voices politely but firmly telling you what to do, whether it is making sure you stand behind the yellow line or cautioning you to ‘mind the gap’. In what way does this tie into the world that the film’s protagonist is journeying through?M: When we started, we tried to sit down and think about the Metro – what was the most apparent thing that we experience on an everyday basis? And it was yellow lines – the lines of division – and the constant instruction of minding the gap. And these lines also give you the codes to conducting yourself in public space – they’re very instructive, very disciplining, from chaos they are trying to organise you. It seemed a good metaphor for gender. Anshuman is trying to conform to these lines, and at the same time trying to negotiate this space a lot. In many of the stories he told us he seemed to want to be invisible – like when he said that he tries not to speak on the phone in a compartment [lest people hear his voice and assume he is not male]. But when two Haryanvi boys on the metro wondered aloud about his gender, he wanted to grab them by the collar and beat them up and create a scene. He tries to follow as well as not follow strict gender divisions – it depends on how much energy he has at the start of that day and whether he wants to be invisible or not.G: There are two protagonists in the documentary – one is Anshuman, and one is the metro. The sounds of the metro help you understand the moralities of the metro. We wanted to juxtapose these sounds through the movie…M: There are also these visuals – there are ads inside and outside the metro that you can see , that are so heteronormative: the LIC ads, the Shaadi.com ads, the fairness cream ads. They are all trying to instruct in you in different ways. What was the best part of working on this film?M: I think it was the rush. The entire shoot was a guerrilla shoot, done on our phones, since photography is banned on the metro and we didn’t have permission. And we were supposed to ‘mind the gap’ and the rules on the metro for our filming, while trying to show Anshuman’s own attempts to mind a gap of a different sort. Were we actually minding the gap? None of us were!What have you learned from working with Anshuman on the film?M: I learned that when you imagine someone who is oppressed because of their identity, you tend to imagine them as being very sad about it and that it would only be a gloomy thing to talk about. But when I met Anshuman, our interactions were so colourful. Every day he would come up with something so interesting, and so joyful, and if there was sadness, he wasn’t bogged down by it. I think I learned that even though you might be someone who is oppressed, you don’t always have to be limited or defined only by that.G: For us, working on this film was a long process and along the way I shared a lot about my life with Anshuman and he shared a lot about his life with me. I think I learned how to be streetsmart, and how to navigate life and work, from him.

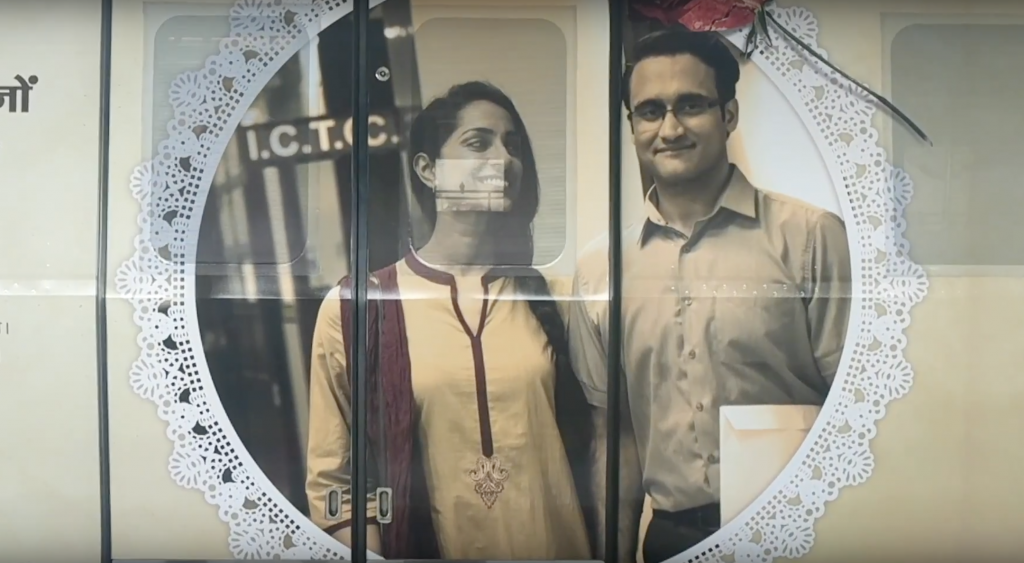

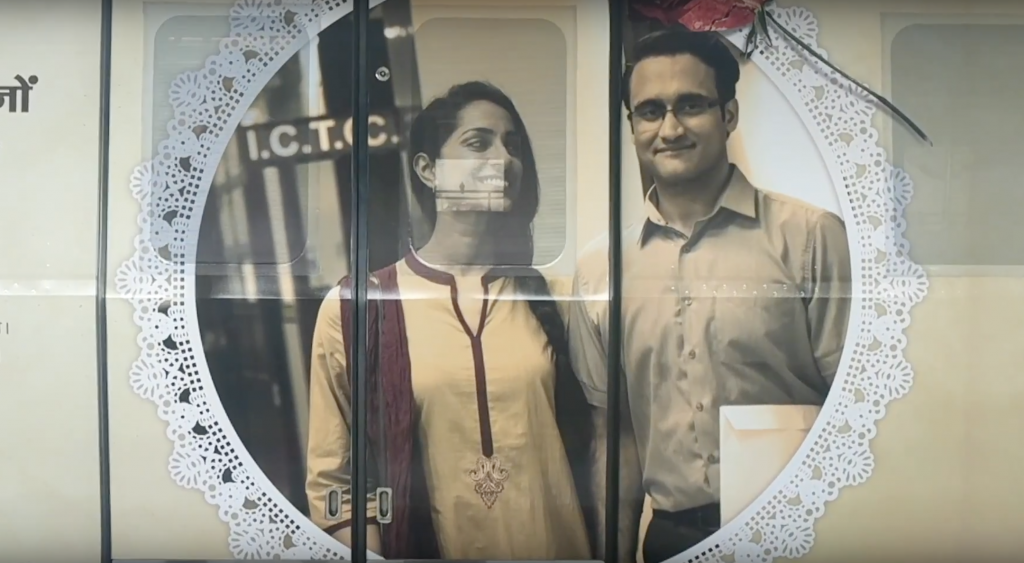

In your film, you include metro announcements, in which you have these very bland authoritative male and female voices politely but firmly telling you what to do, whether it is making sure you stand behind the yellow line or cautioning you to ‘mind the gap’. In what way does this tie into the world that the film’s protagonist is journeying through?M: When we started, we tried to sit down and think about the Metro – what was the most apparent thing that we experience on an everyday basis? And it was yellow lines – the lines of division – and the constant instruction of minding the gap. And these lines also give you the codes to conducting yourself in public space – they’re very instructive, very disciplining, from chaos they are trying to organise you. It seemed a good metaphor for gender. Anshuman is trying to conform to these lines, and at the same time trying to negotiate this space a lot. In many of the stories he told us he seemed to want to be invisible – like when he said that he tries not to speak on the phone in a compartment [lest people hear his voice and assume he is not male]. But when two Haryanvi boys on the metro wondered aloud about his gender, he wanted to grab them by the collar and beat them up and create a scene. He tries to follow as well as not follow strict gender divisions – it depends on how much energy he has at the start of that day and whether he wants to be invisible or not.G: There are two protagonists in the documentary – one is Anshuman, and one is the metro. The sounds of the metro help you understand the moralities of the metro. We wanted to juxtapose these sounds through the movie…M: There are also these visuals – there are ads inside and outside the metro that you can see , that are so heteronormative: the LIC ads, the Shaadi.com ads, the fairness cream ads. They are all trying to instruct in you in different ways. What was the best part of working on this film?M: I think it was the rush. The entire shoot was a guerrilla shoot, done on our phones, since photography is banned on the metro and we didn’t have permission. And we were supposed to ‘mind the gap’ and the rules on the metro for our filming, while trying to show Anshuman’s own attempts to mind a gap of a different sort. Were we actually minding the gap? None of us were!What have you learned from working with Anshuman on the film?M: I learned that when you imagine someone who is oppressed because of their identity, you tend to imagine them as being very sad about it and that it would only be a gloomy thing to talk about. But when I met Anshuman, our interactions were so colourful. Every day he would come up with something so interesting, and so joyful, and if there was sadness, he wasn’t bogged down by it. I think I learned that even though you might be someone who is oppressed, you don’t always have to be limited or defined only by that.G: For us, working on this film was a long process and along the way I shared a lot about my life with Anshuman and he shared a lot about his life with me. I think I learned how to be streetsmart, and how to navigate life and work, from him.

Did this change in plan come about right at the research stage?G: Yes. Delhi is a place where many people migrate to because of their sexuality – the queer movement is very strong in Delhi. Right at the beginning we were told that because we were outsiders, and not from the queer community, we would have to make sure we did a lot of research – we couldn’t make any mistakes. That was great advice and it helped us a lot. We did a lot of research and didn’t just rely on our immediate circle of friends. At first, we didn’t meet Anshuman as the person we would work with so closely – he was initially introducing us to other people for our research because he worked with rights organisations.M: And also while researching, Anshuman was very forthcoming and eventually we became friends with him. So the process became easier because we would hang out with him all the time, and it became very natural for us to work with him.What about Anshuman drew you to him for this film?M: He was so forthcoming, he would always ensure that we were comfortable, if there was a serious moment he would crack a joke to lighten the mood – it was really beautiful. It felt like we were caring for him and he was caring for us. It became a relationship that was beyond this project. G: The film starts with the opening of a new metro line – he was the one who said, listen, there’s a new line opening, aaj chalte hain. He would give us suggestions and ideas.This film is largely about gender and sexuality, but it is not a narrow look at it by any means – when we see Anshuman, being trans might be a large facet of his identity, but it is still only one facet of many. We’re introduced to a charming, lovable person navigating a city, navigating identity, and navigating pleasure. Was that always the plan?M: As first-time filmmakers, we got a lot of advice from PSBT, and were encouraged to look at whatever we were making a film about as a whole. That was very ingrained in us – that we shouldn’t objectify the people we are working with for the film. Also, just given the kind of person Anshuman is, and the kind of bond we have with him, we couldn’t look at him just for his gender identity. We became friends, and you don’t see your friends as only one thing, right? So it happened naturally too.The entire film is shot on the Delhi metro, with Anshuman travelling up and down on its lines, talking about his life and interactions with other people on the metro. Why did you choose to focus on the metro?M: Because it’s a place in which I spend at least one-fourth of my day. It’s a space that feels so interesting – you get to see so much, and learn so much about other people, so I had always wanted to work on something related to the metro.

Did this change in plan come about right at the research stage?G: Yes. Delhi is a place where many people migrate to because of their sexuality – the queer movement is very strong in Delhi. Right at the beginning we were told that because we were outsiders, and not from the queer community, we would have to make sure we did a lot of research – we couldn’t make any mistakes. That was great advice and it helped us a lot. We did a lot of research and didn’t just rely on our immediate circle of friends. At first, we didn’t meet Anshuman as the person we would work with so closely – he was initially introducing us to other people for our research because he worked with rights organisations.M: And also while researching, Anshuman was very forthcoming and eventually we became friends with him. So the process became easier because we would hang out with him all the time, and it became very natural for us to work with him.What about Anshuman drew you to him for this film?M: He was so forthcoming, he would always ensure that we were comfortable, if there was a serious moment he would crack a joke to lighten the mood – it was really beautiful. It felt like we were caring for him and he was caring for us. It became a relationship that was beyond this project. G: The film starts with the opening of a new metro line – he was the one who said, listen, there’s a new line opening, aaj chalte hain. He would give us suggestions and ideas.This film is largely about gender and sexuality, but it is not a narrow look at it by any means – when we see Anshuman, being trans might be a large facet of his identity, but it is still only one facet of many. We’re introduced to a charming, lovable person navigating a city, navigating identity, and navigating pleasure. Was that always the plan?M: As first-time filmmakers, we got a lot of advice from PSBT, and were encouraged to look at whatever we were making a film about as a whole. That was very ingrained in us – that we shouldn’t objectify the people we are working with for the film. Also, just given the kind of person Anshuman is, and the kind of bond we have with him, we couldn’t look at him just for his gender identity. We became friends, and you don’t see your friends as only one thing, right? So it happened naturally too.The entire film is shot on the Delhi metro, with Anshuman travelling up and down on its lines, talking about his life and interactions with other people on the metro. Why did you choose to focus on the metro?M: Because it’s a place in which I spend at least one-fourth of my day. It’s a space that feels so interesting – you get to see so much, and learn so much about other people, so I had always wanted to work on something related to the metro. In your film, you include metro announcements, in which you have these very bland authoritative male and female voices politely but firmly telling you what to do, whether it is making sure you stand behind the yellow line or cautioning you to ‘mind the gap’. In what way does this tie into the world that the film’s protagonist is journeying through?M: When we started, we tried to sit down and think about the Metro – what was the most apparent thing that we experience on an everyday basis? And it was yellow lines – the lines of division – and the constant instruction of minding the gap. And these lines also give you the codes to conducting yourself in public space – they’re very instructive, very disciplining, from chaos they are trying to organise you. It seemed a good metaphor for gender. Anshuman is trying to conform to these lines, and at the same time trying to negotiate this space a lot. In many of the stories he told us he seemed to want to be invisible – like when he said that he tries not to speak on the phone in a compartment [lest people hear his voice and assume he is not male]. But when two Haryanvi boys on the metro wondered aloud about his gender, he wanted to grab them by the collar and beat them up and create a scene. He tries to follow as well as not follow strict gender divisions – it depends on how much energy he has at the start of that day and whether he wants to be invisible or not.G: There are two protagonists in the documentary – one is Anshuman, and one is the metro. The sounds of the metro help you understand the moralities of the metro. We wanted to juxtapose these sounds through the movie…M: There are also these visuals – there are ads inside and outside the metro that you can see , that are so heteronormative: the LIC ads, the Shaadi.com ads, the fairness cream ads. They are all trying to instruct in you in different ways. What was the best part of working on this film?M: I think it was the rush. The entire shoot was a guerrilla shoot, done on our phones, since photography is banned on the metro and we didn’t have permission. And we were supposed to ‘mind the gap’ and the rules on the metro for our filming, while trying to show Anshuman’s own attempts to mind a gap of a different sort. Were we actually minding the gap? None of us were!What have you learned from working with Anshuman on the film?M: I learned that when you imagine someone who is oppressed because of their identity, you tend to imagine them as being very sad about it and that it would only be a gloomy thing to talk about. But when I met Anshuman, our interactions were so colourful. Every day he would come up with something so interesting, and so joyful, and if there was sadness, he wasn’t bogged down by it. I think I learned that even though you might be someone who is oppressed, you don’t always have to be limited or defined only by that.G: For us, working on this film was a long process and along the way I shared a lot about my life with Anshuman and he shared a lot about his life with me. I think I learned how to be streetsmart, and how to navigate life and work, from him.

In your film, you include metro announcements, in which you have these very bland authoritative male and female voices politely but firmly telling you what to do, whether it is making sure you stand behind the yellow line or cautioning you to ‘mind the gap’. In what way does this tie into the world that the film’s protagonist is journeying through?M: When we started, we tried to sit down and think about the Metro – what was the most apparent thing that we experience on an everyday basis? And it was yellow lines – the lines of division – and the constant instruction of minding the gap. And these lines also give you the codes to conducting yourself in public space – they’re very instructive, very disciplining, from chaos they are trying to organise you. It seemed a good metaphor for gender. Anshuman is trying to conform to these lines, and at the same time trying to negotiate this space a lot. In many of the stories he told us he seemed to want to be invisible – like when he said that he tries not to speak on the phone in a compartment [lest people hear his voice and assume he is not male]. But when two Haryanvi boys on the metro wondered aloud about his gender, he wanted to grab them by the collar and beat them up and create a scene. He tries to follow as well as not follow strict gender divisions – it depends on how much energy he has at the start of that day and whether he wants to be invisible or not.G: There are two protagonists in the documentary – one is Anshuman, and one is the metro. The sounds of the metro help you understand the moralities of the metro. We wanted to juxtapose these sounds through the movie…M: There are also these visuals – there are ads inside and outside the metro that you can see , that are so heteronormative: the LIC ads, the Shaadi.com ads, the fairness cream ads. They are all trying to instruct in you in different ways. What was the best part of working on this film?M: I think it was the rush. The entire shoot was a guerrilla shoot, done on our phones, since photography is banned on the metro and we didn’t have permission. And we were supposed to ‘mind the gap’ and the rules on the metro for our filming, while trying to show Anshuman’s own attempts to mind a gap of a different sort. Were we actually minding the gap? None of us were!What have you learned from working with Anshuman on the film?M: I learned that when you imagine someone who is oppressed because of their identity, you tend to imagine them as being very sad about it and that it would only be a gloomy thing to talk about. But when I met Anshuman, our interactions were so colourful. Every day he would come up with something so interesting, and so joyful, and if there was sadness, he wasn’t bogged down by it. I think I learned that even though you might be someone who is oppressed, you don’t always have to be limited or defined only by that.G: For us, working on this film was a long process and along the way I shared a lot about my life with Anshuman and he shared a lot about his life with me. I think I learned how to be streetsmart, and how to navigate life and work, from him.