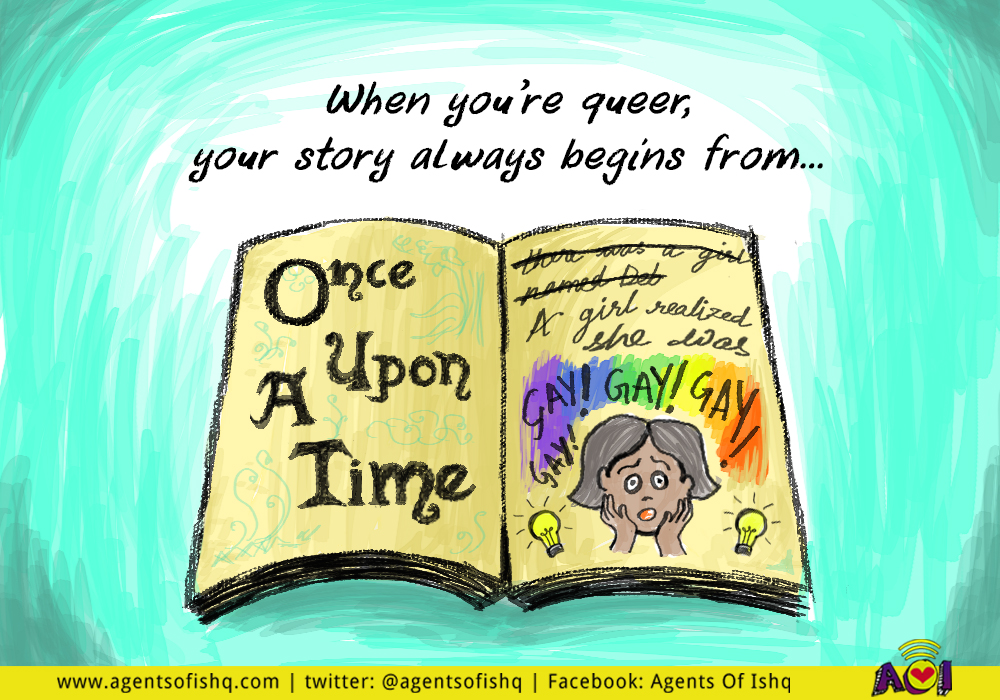

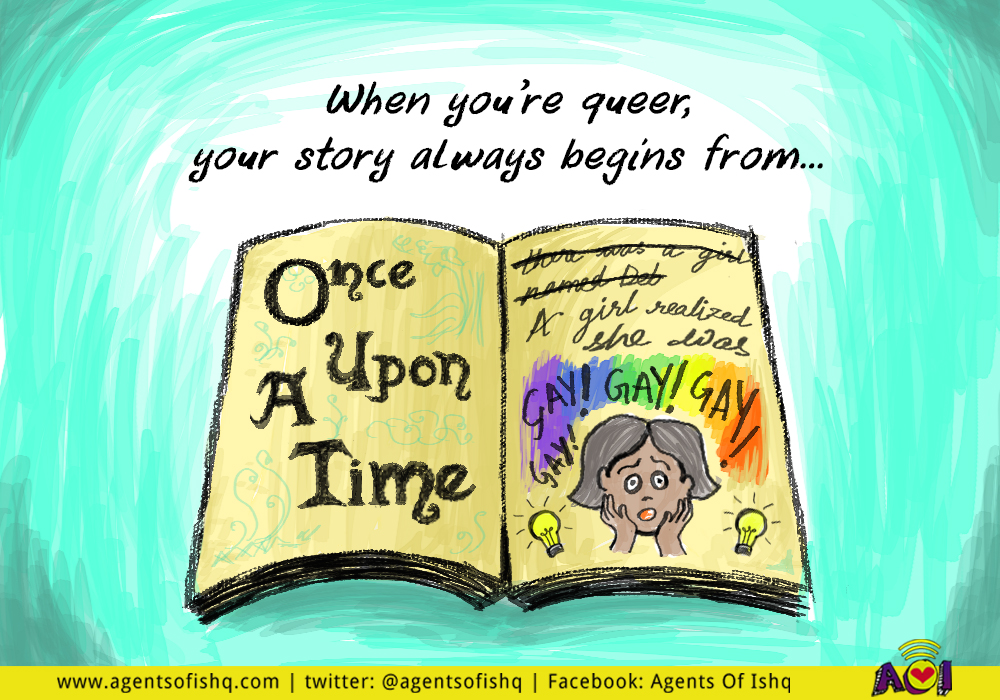

My identity as a queer person became a bit of a shield to protect myself from the turbulence that comes with one’s private life, in the world of love, in the world of sex It is little-known among those in my circle that I serially crushed on boys (one per year) upto Class 8. Maybe it’s because after the last boy I liked, I realised I was queer. And when you’re queer, your story always begins from the moment you knew you were gay. From the moment you identified yourself as something different. As someone whose ability to desire and love required a label to be explained to everyone else. What was my sexuality before I knew? I don’t know – and it seems no one is really curious.

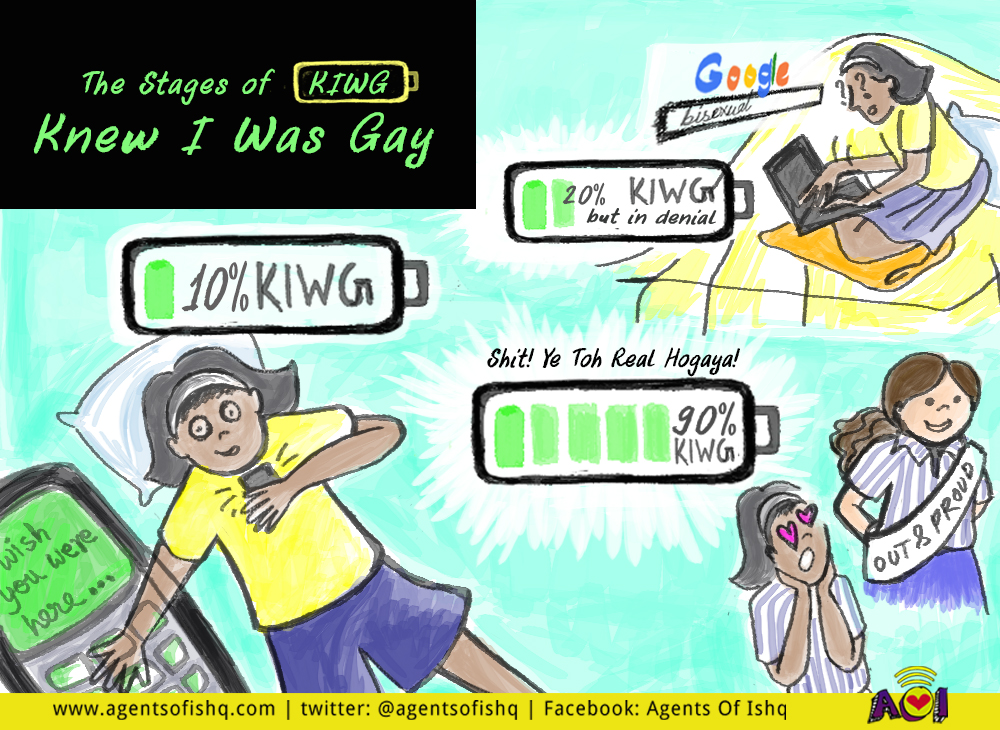

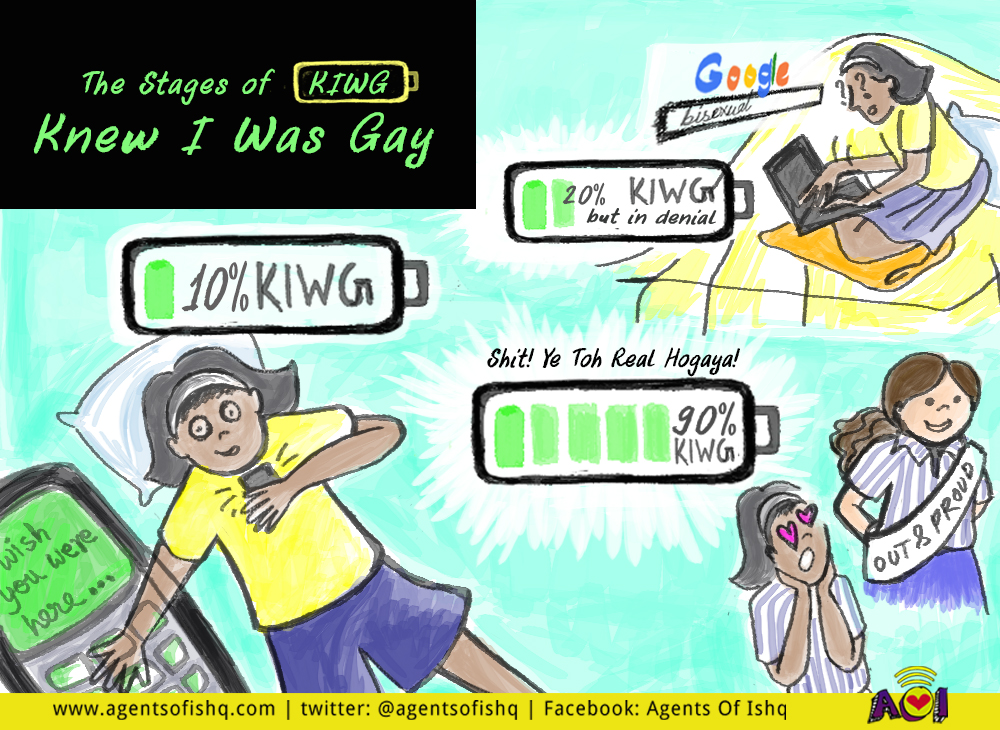

It is little-known among those in my circle that I serially crushed on boys (one per year) upto Class 8. Maybe it’s because after the last boy I liked, I realised I was queer. And when you’re queer, your story always begins from the moment you knew you were gay. From the moment you identified yourself as something different. As someone whose ability to desire and love required a label to be explained to everyone else. What was my sexuality before I knew? I don’t know – and it seems no one is really curious. I knew I was queer at different points in my life with different degrees of clarity. In 8th grade, when my heart did a somersault instead of the usual dhadko-fying when my Woman-Crush-Wednesday friend I was obsessed with sent me a text saying “I wish you were here”, I was at 10% “Knew I Was Gay (KIWG)”. When I googled bisexual and felt like, “Whoa, I can love love my friend?” I was at 20% but-in-denial KIWG. When in Class12 a girl told me she was a lesbian and I, ahem, promptly fell for her, I peaked at a 90% shit-ye-toh-real-ho-gaya KIWG.

I knew I was queer at different points in my life with different degrees of clarity. In 8th grade, when my heart did a somersault instead of the usual dhadko-fying when my Woman-Crush-Wednesday friend I was obsessed with sent me a text saying “I wish you were here”, I was at 10% “Knew I Was Gay (KIWG)”. When I googled bisexual and felt like, “Whoa, I can love love my friend?” I was at 20% but-in-denial KIWG. When in Class12 a girl told me she was a lesbian and I, ahem, promptly fell for her, I peaked at a 90% shit-ye-toh-real-ho-gaya KIWG. Thing is, I knew about LGBT rights and considered myself an ally very early. Before I even knew I was queer, I knew the term, the movement for their rights, the language of identity politics. I was already feministing, and when people called my best friend ‘corrupt’ (a word used generously in middle school) for having too many friends who were boys, I could call it “slut-shaming”. It was that time in my life when these words for experiences felt like they were liberating me. So when I finally knew I was gay, was I happy to have an identity that held some socio-political significance? A little I guess. It did make me feel a bit like a krantikari. But soon I just got really really confused.

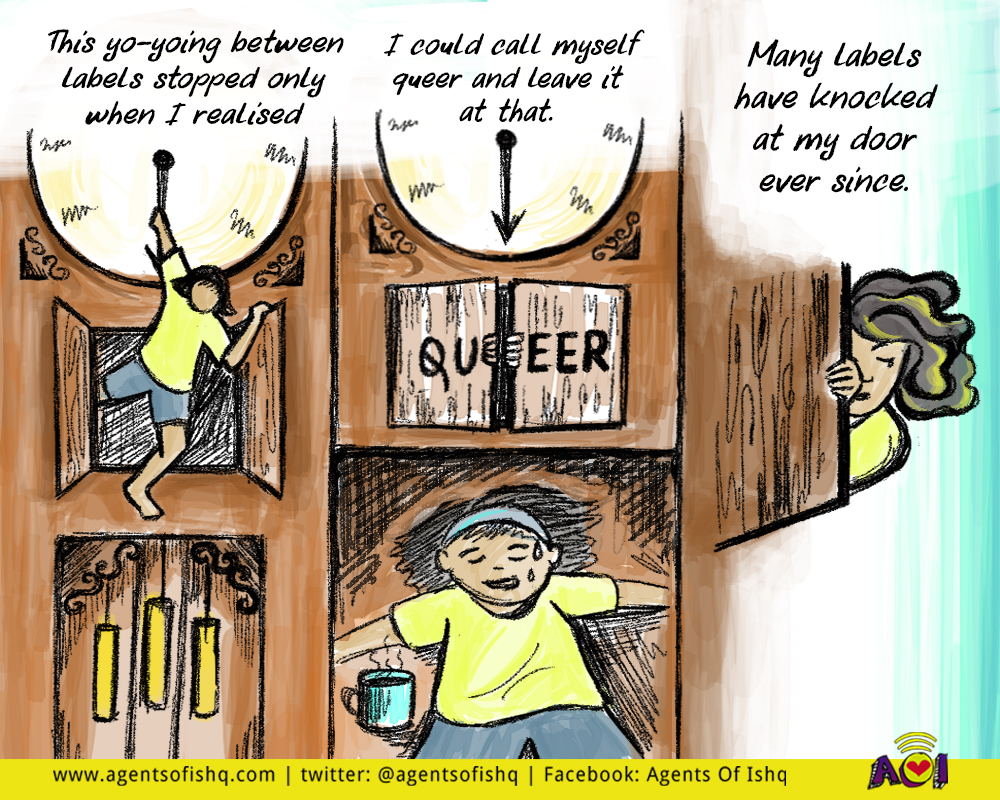

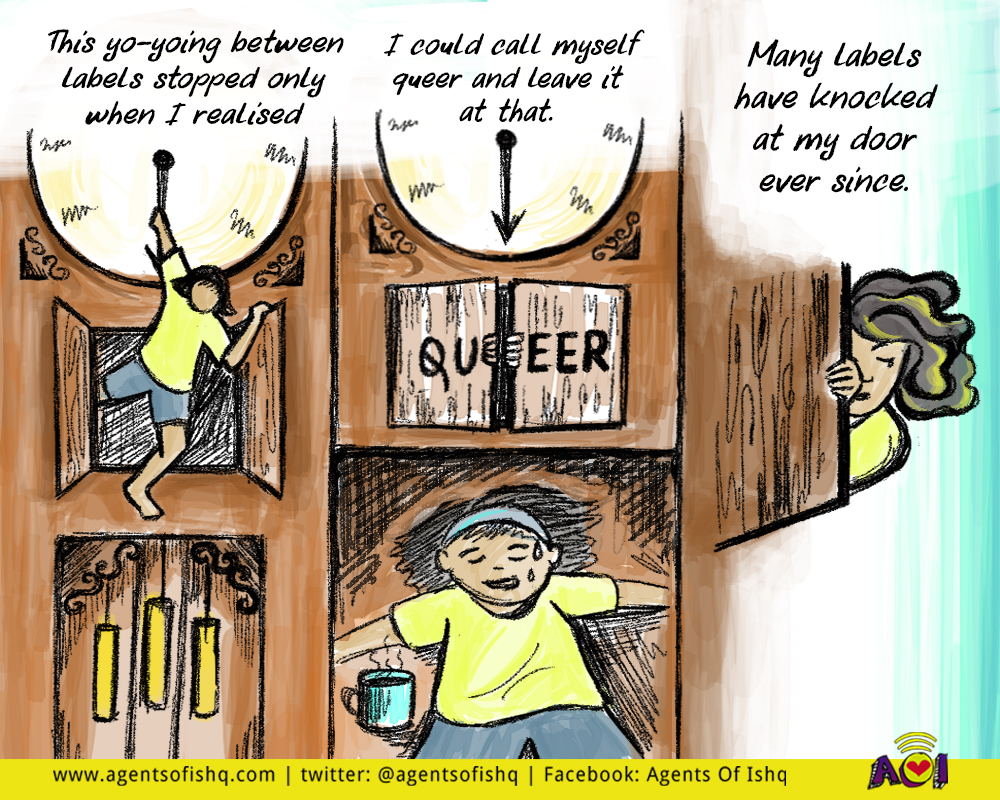

Thing is, I knew about LGBT rights and considered myself an ally very early. Before I even knew I was queer, I knew the term, the movement for their rights, the language of identity politics. I was already feministing, and when people called my best friend ‘corrupt’ (a word used generously in middle school) for having too many friends who were boys, I could call it “slut-shaming”. It was that time in my life when these words for experiences felt like they were liberating me. So when I finally knew I was gay, was I happy to have an identity that held some socio-political significance? A little I guess. It did make me feel a bit like a krantikari. But soon I just got really really confused. Was I bisexual? But I hadn’t liked guys in years by then. Was I *gasp* a homoromantic heterosexual? I seemed to fall in love with women more than lust after them. Lesbian? But what about that dirty history of light-eyed boys I had crushes on? Who’d believe me if I said lesbian? This yo-yoing between labels stopped only when I realised I could call myself queer and leave it at that. And yet – that finding of the perfect word never really stopped. Many labels have knocked at my door ever since. Gender-fluid. Asexual. Demi-sexual. Anorgasmic. Sensual-sexual (my invention). Woman. Lesbian pays a monthly visit, I swear. And in moments of sheer terror, Actually Straight (You’re Just Faking It) comes says hi. For a year or so before I entered college, every second thought was about this, occupying my mental space much more than I’d expected. I thought I was obsessed. In that time somewhere in that relentless negotiation of determining who I was, I left behind my ability to fall in love or desire without the baggage of my queer identity. I pretend that the era of liking boys is irrelevant but perhaps it was the only time my sexuality was really just mine. Not a part of a larger discourse. Not different. Not relevant to anything or anyone but myself.

Was I bisexual? But I hadn’t liked guys in years by then. Was I *gasp* a homoromantic heterosexual? I seemed to fall in love with women more than lust after them. Lesbian? But what about that dirty history of light-eyed boys I had crushes on? Who’d believe me if I said lesbian? This yo-yoing between labels stopped only when I realised I could call myself queer and leave it at that. And yet – that finding of the perfect word never really stopped. Many labels have knocked at my door ever since. Gender-fluid. Asexual. Demi-sexual. Anorgasmic. Sensual-sexual (my invention). Woman. Lesbian pays a monthly visit, I swear. And in moments of sheer terror, Actually Straight (You’re Just Faking It) comes says hi. For a year or so before I entered college, every second thought was about this, occupying my mental space much more than I’d expected. I thought I was obsessed. In that time somewhere in that relentless negotiation of determining who I was, I left behind my ability to fall in love or desire without the baggage of my queer identity. I pretend that the era of liking boys is irrelevant but perhaps it was the only time my sexuality was really just mine. Not a part of a larger discourse. Not different. Not relevant to anything or anyone but myself. When I went to college, I was starting to know who I was. Although if I have to phrase it more honestly, I was starting to get better at explaining what I identified as. I started coming out to people and found solace in making queer art that further cemented me in people’s eyes as that Queer person. My work really was my refuge. While I was falling in love with close friends who were straight, roommates, beautiful seniors (basically everyone, the emotional ho that I was), I’d try to find answers through my work. When I was confused about why I sucked at understanding romance or approaching it, I analysed my queerness to death and made an animation that explained how heterosexuals had unlimited media to guide them in their love life, but us queers had nothing to teach us. When I was heartbroken and no politics could explain it, I would draw, and dump it in my Instagram. I’m still mentioned in some articles as a queer Insta artist (I call myself gay Rupi Kaur in private).

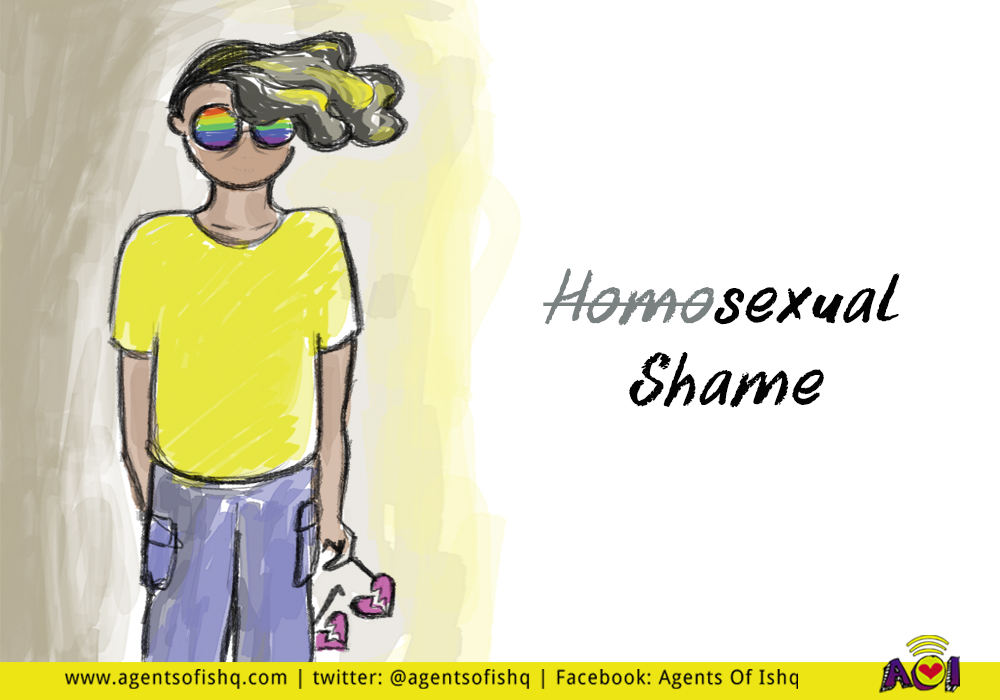

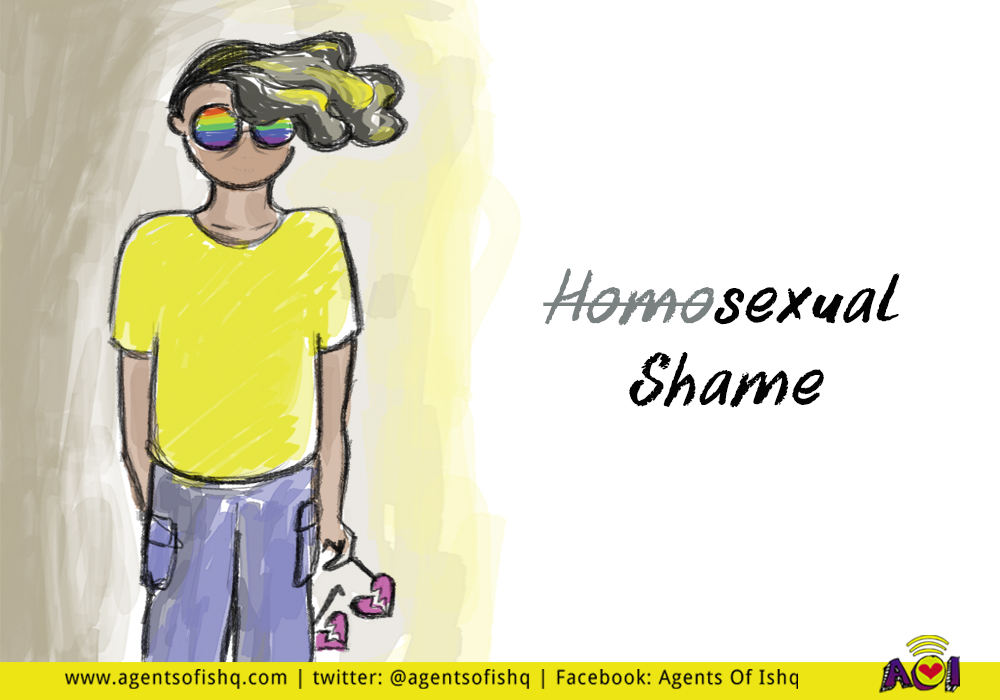

When I went to college, I was starting to know who I was. Although if I have to phrase it more honestly, I was starting to get better at explaining what I identified as. I started coming out to people and found solace in making queer art that further cemented me in people’s eyes as that Queer person. My work really was my refuge. While I was falling in love with close friends who were straight, roommates, beautiful seniors (basically everyone, the emotional ho that I was), I’d try to find answers through my work. When I was confused about why I sucked at understanding romance or approaching it, I analysed my queerness to death and made an animation that explained how heterosexuals had unlimited media to guide them in their love life, but us queers had nothing to teach us. When I was heartbroken and no politics could explain it, I would draw, and dump it in my Instagram. I’m still mentioned in some articles as a queer Insta artist (I call myself gay Rupi Kaur in private). My personal would always be political. So I took advantage of it and made a portfolio out of it. I was building a reputation as that Queer person, as that Queer artist, among my friends as that relentlessly gay friend. In truth just as a person, I had no clue how to navigate my love and sex life. I had placed all my value in making my identity useful – in changing the world, in articulating a politics, and I always prioritised it over (or perhaps even interchanged it with) my actual personal life. I was out and proud, but inside I found myself unexpectedly stumbling upon shame more and more. That shame though, was not about being queer.

My personal would always be political. So I took advantage of it and made a portfolio out of it. I was building a reputation as that Queer person, as that Queer artist, among my friends as that relentlessly gay friend. In truth just as a person, I had no clue how to navigate my love and sex life. I had placed all my value in making my identity useful – in changing the world, in articulating a politics, and I always prioritised it over (or perhaps even interchanged it with) my actual personal life. I was out and proud, but inside I found myself unexpectedly stumbling upon shame more and more. That shame though, was not about being queer. The better half of every ‘It Gets Better’ narrative starts with coming out. I had already done that. I already knew that liking, loving, desiring women was okay. But my personal life still felt...deeply sad. Whenever I fell for someone, the impossibility of it all would fall like a great weight on me. I was afraid of falling in love, because every time the person was either straight or not interested in me. I taught myself to confess my feelings but only did it when I was already in too deep. I didn’t know how to flirt or test the waters with someone because I was at a stage where just the prospect of befriending a queer person itself would freak me out, forget expressing romantic or sexual interest in them. In college we were surrounded by romancing and sexing and hormones flying around. But I felt completely in the dark about how sexual interactions happened, let alone know how to engage in them myself.

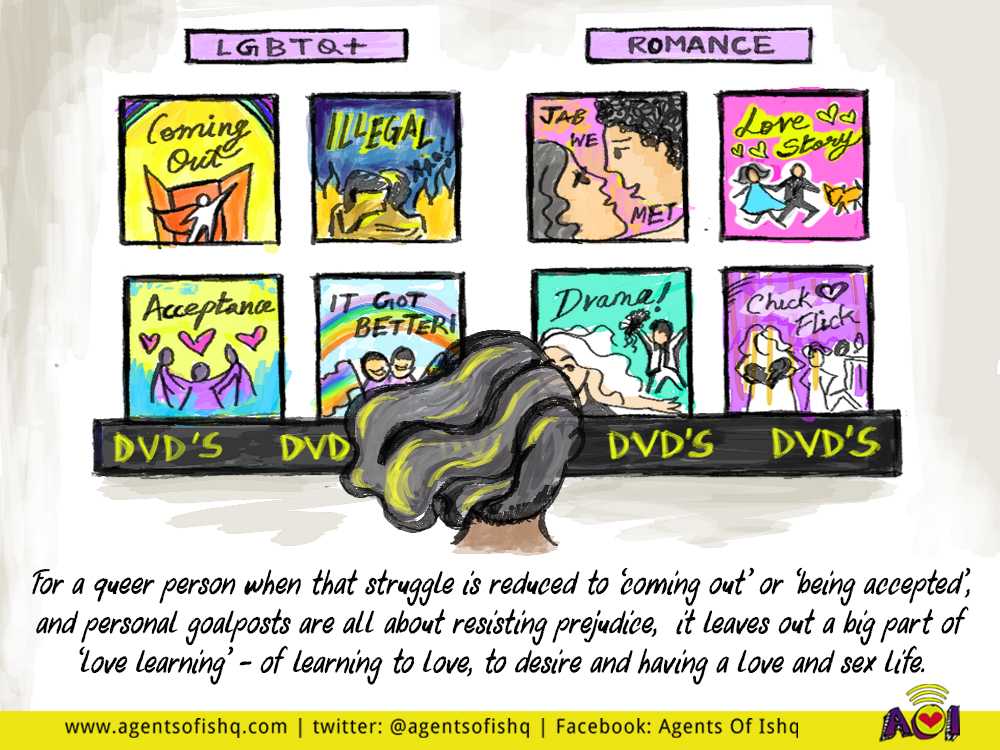

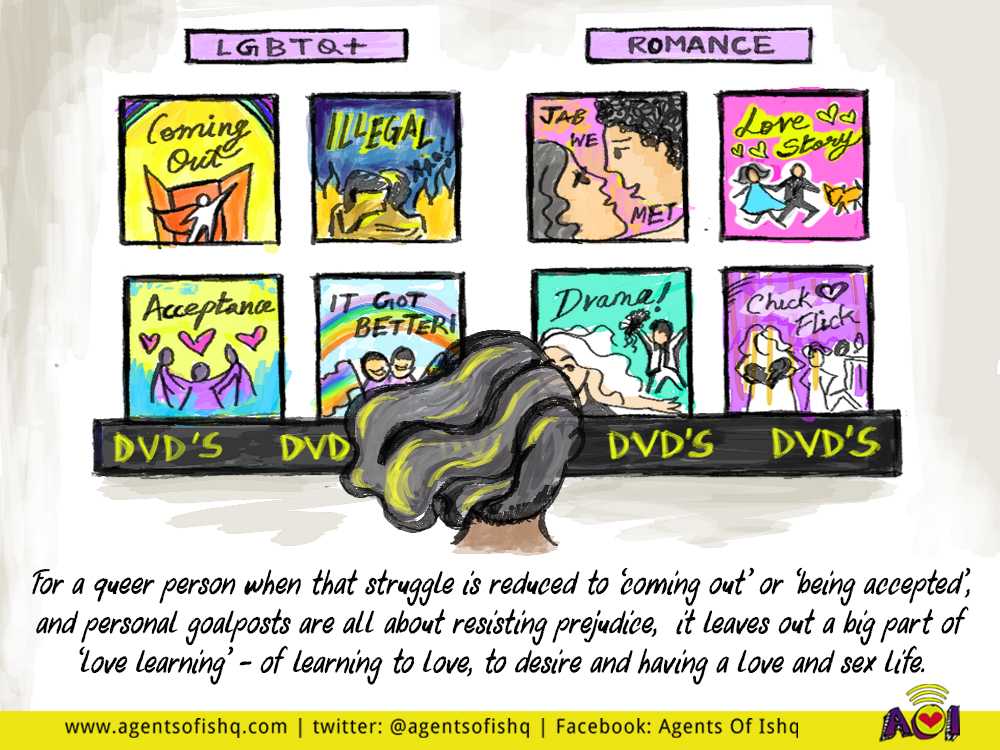

The better half of every ‘It Gets Better’ narrative starts with coming out. I had already done that. I already knew that liking, loving, desiring women was okay. But my personal life still felt...deeply sad. Whenever I fell for someone, the impossibility of it all would fall like a great weight on me. I was afraid of falling in love, because every time the person was either straight or not interested in me. I taught myself to confess my feelings but only did it when I was already in too deep. I didn’t know how to flirt or test the waters with someone because I was at a stage where just the prospect of befriending a queer person itself would freak me out, forget expressing romantic or sexual interest in them. In college we were surrounded by romancing and sexing and hormones flying around. But I felt completely in the dark about how sexual interactions happened, let alone know how to engage in them myself. I think I never was able to spot a queer person and just befriend them because somewhere I had convinced myself that if I was in a supportive environment, who was I to ask for more? I felt silly for wanting a community, wanting to seek out more queer people, for being single and utterly inexperienced in my personal life in spite of being in a liberal art school where according to other Bangaloreans, “every second person is bisexual”. If there was a word for cruising for queer women, I would have sucked at it. Whenever I went to queer events, the utter confidence with which people oozed sexuality or openly flirted with each other only served to reinforce my insecurities, because I just didn’t know how to get there. I was ashamed of struggling with my sexuality long after having done the entire I’m Out and Proud thing. I guess what I didn’t realise was that more than anything else, I was struggling with being sexual, not homosexual. Which may not be different from anyone else, but for a queer person when that struggle is reduced to ‘coming out’ or ‘being accepted’, and personal goalposts are all about resisting prejudice, it leaves out a big part of ‘love learning’ – of learning to love, to desire, and having a love and sex life.

I think I never was able to spot a queer person and just befriend them because somewhere I had convinced myself that if I was in a supportive environment, who was I to ask for more? I felt silly for wanting a community, wanting to seek out more queer people, for being single and utterly inexperienced in my personal life in spite of being in a liberal art school where according to other Bangaloreans, “every second person is bisexual”. If there was a word for cruising for queer women, I would have sucked at it. Whenever I went to queer events, the utter confidence with which people oozed sexuality or openly flirted with each other only served to reinforce my insecurities, because I just didn’t know how to get there. I was ashamed of struggling with my sexuality long after having done the entire I’m Out and Proud thing. I guess what I didn’t realise was that more than anything else, I was struggling with being sexual, not homosexual. Which may not be different from anyone else, but for a queer person when that struggle is reduced to ‘coming out’ or ‘being accepted’, and personal goalposts are all about resisting prejudice, it leaves out a big part of ‘love learning’ – of learning to love, to desire, and having a love and sex life. I used to try to find the answers to all my struggles in my queerness and to some extent it did help to be reassured that, yes, it was more difficult to find love as a queer person because – statistical odds, haha, and that, yes, I didn’t get any training from real life or media on dating as a queer woman. But this ended up blinding me to something more fundamental: that a lot of my insecurities stemmed from sexual shame, not necessarily because I was queer.

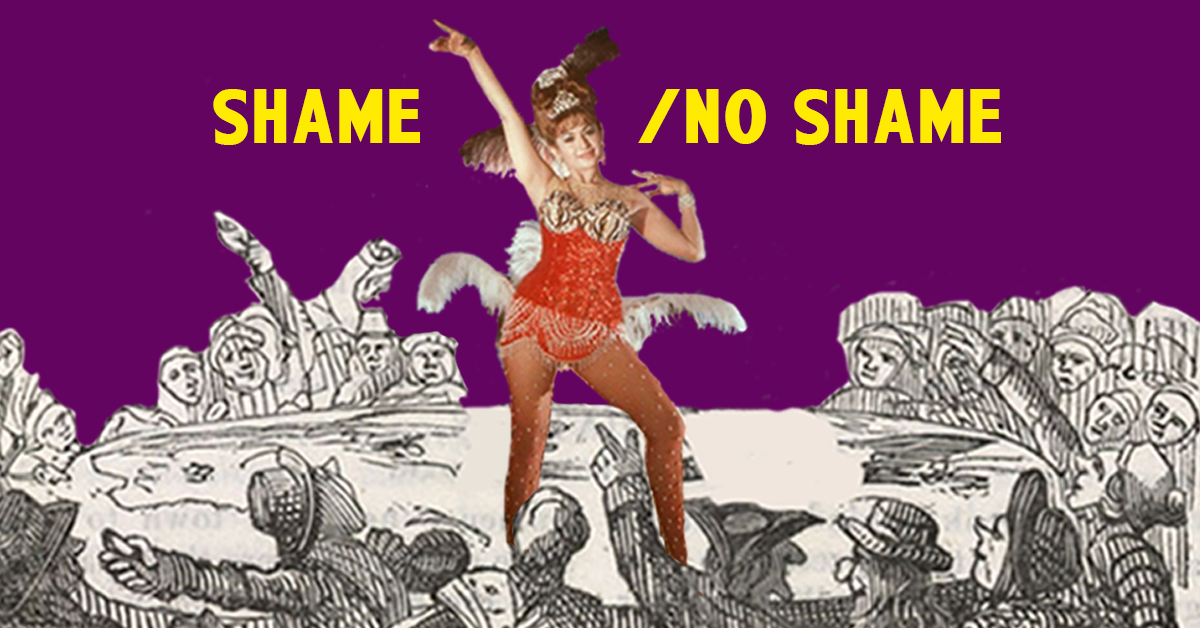

I used to try to find the answers to all my struggles in my queerness and to some extent it did help to be reassured that, yes, it was more difficult to find love as a queer person because – statistical odds, haha, and that, yes, I didn’t get any training from real life or media on dating as a queer woman. But this ended up blinding me to something more fundamental: that a lot of my insecurities stemmed from sexual shame, not necessarily because I was queer. I may have discovered myself straightaway in identity politics (and I am truly glad I skipped the “Oh shit I’m an abomination this isn’t normal” phase), but my identity as a queer person soon became a bit of a shield to protect myself from the turbulence that comes with one’s private life, in the world of love, in the world of sex. I didn’t take my steps into these worlds because it got easy to foreground my queerness and ignore the fact that I wanted love and sex as a person, not for the sake of ideology. And somewhere it was easy to ignore it, because I have in many ways been taught to think of relationships and sex as an indulgent and unimportant. It was easier to say I was queer and think it was socially and politically relevant, than to say I was queer and I wanted to know more people like me to befriend or date. Even when I tried to create a safe space in college, my first fear was, “What if people think I’m doing this just to find people to date?” To be seen as wanting love and pleasure at the most basic human level – that’s an emotional shame no one seemed to be talking about. Even the most woke of people around me would never be caught dead admitting to actively looking for intimacy (ahem ahem, Tinder shamers). To admit to being lonely was to let down ‘the cause’.

I may have discovered myself straightaway in identity politics (and I am truly glad I skipped the “Oh shit I’m an abomination this isn’t normal” phase), but my identity as a queer person soon became a bit of a shield to protect myself from the turbulence that comes with one’s private life, in the world of love, in the world of sex. I didn’t take my steps into these worlds because it got easy to foreground my queerness and ignore the fact that I wanted love and sex as a person, not for the sake of ideology. And somewhere it was easy to ignore it, because I have in many ways been taught to think of relationships and sex as an indulgent and unimportant. It was easier to say I was queer and think it was socially and politically relevant, than to say I was queer and I wanted to know more people like me to befriend or date. Even when I tried to create a safe space in college, my first fear was, “What if people think I’m doing this just to find people to date?” To be seen as wanting love and pleasure at the most basic human level – that’s an emotional shame no one seemed to be talking about. Even the most woke of people around me would never be caught dead admitting to actively looking for intimacy (ahem ahem, Tinder shamers). To admit to being lonely was to let down ‘the cause’. I think my turning point for acknowledging and dealing with this shame firsthand happened when I joined Tinder. I owe Tinder-Bhai a lot. It was my first and best wingman and pushed me to do what I desired in my private life more than anyone else. I did get some flak because of it because not many around me really took Tinder seriously. I first got on it during an exchange programme because it was so far away from home. I even managed to bring my date over for dinner at my dorm, and overcame that fear of being seen as a sexual dating being. Back in India it took some time and (yet another) glorious heartbreak to push me back into the dating world. Tinder allowed me to see myself as a queer being, but through a more personal lens. I sexted for the first time. Went on dates. Learnt to gauge and express interest. Sent pictures of the moon. Talked. Talked a lot. I not only started learning how people find sexual or romantic partners, but also ended up meeting a lot of queer women I had these personal conversations with, conversations I never realised I needed to have. Tinder made me overcome my shame of actively wanting more queer friends and made me take the first trembling steps to a support group. I don’t know how to express the utter relief that came with being able to do these without berating myself for “asking for too much”. I wish there was an easy way to explain to the world that wanting intimacy isn’t shameful, to tell my mother that my lovers are as important to me as family, and that Tinder is my favourite place sometimes.

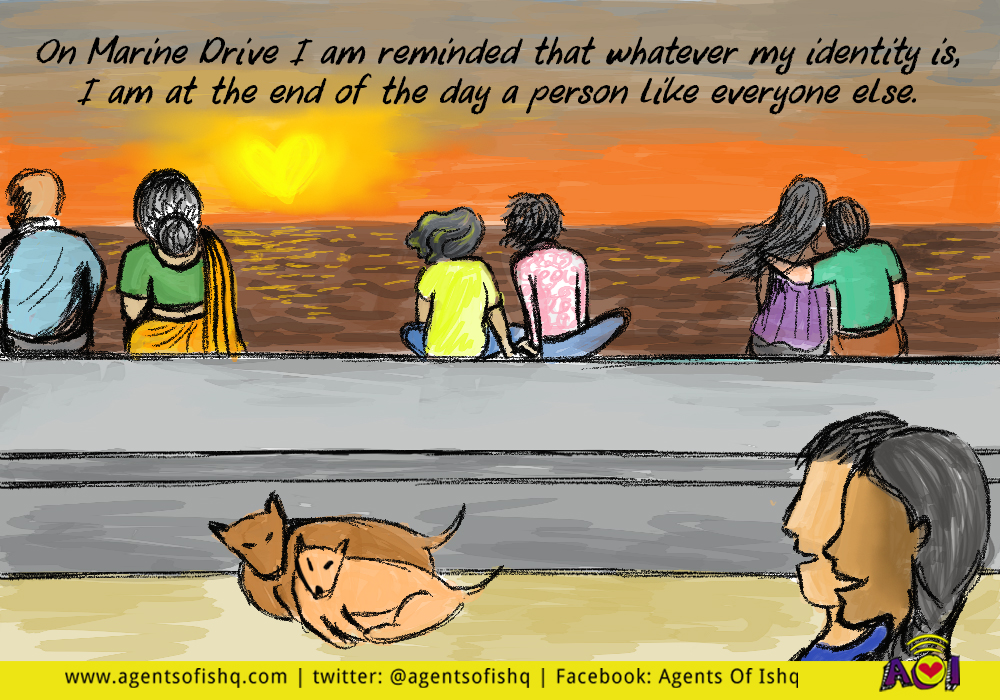

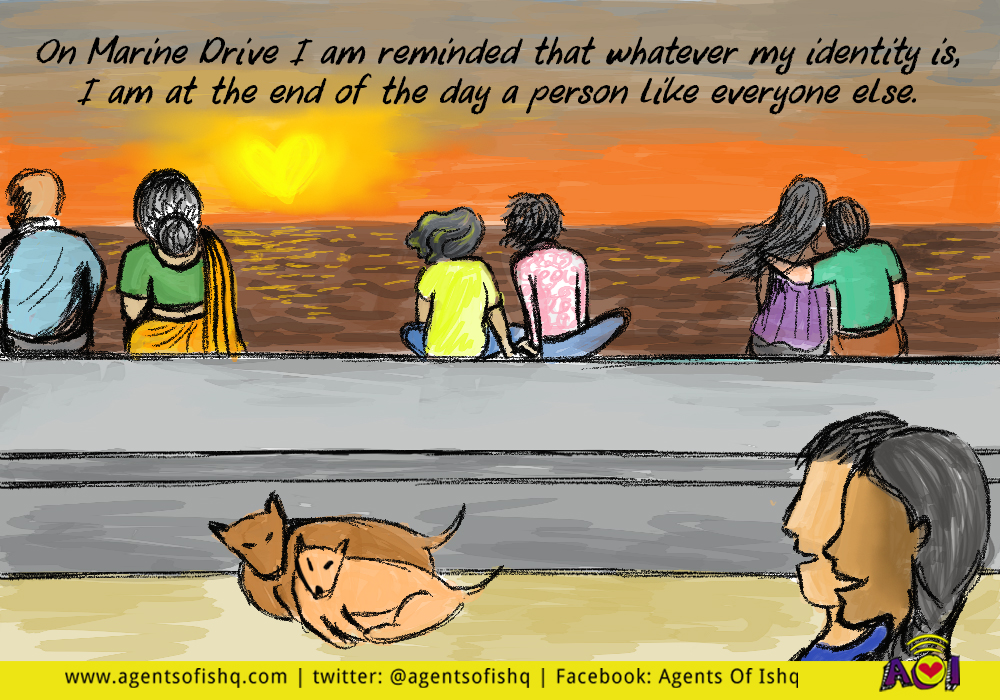

I think my turning point for acknowledging and dealing with this shame firsthand happened when I joined Tinder. I owe Tinder-Bhai a lot. It was my first and best wingman and pushed me to do what I desired in my private life more than anyone else. I did get some flak because of it because not many around me really took Tinder seriously. I first got on it during an exchange programme because it was so far away from home. I even managed to bring my date over for dinner at my dorm, and overcame that fear of being seen as a sexual dating being. Back in India it took some time and (yet another) glorious heartbreak to push me back into the dating world. Tinder allowed me to see myself as a queer being, but through a more personal lens. I sexted for the first time. Went on dates. Learnt to gauge and express interest. Sent pictures of the moon. Talked. Talked a lot. I not only started learning how people find sexual or romantic partners, but also ended up meeting a lot of queer women I had these personal conversations with, conversations I never realised I needed to have. Tinder made me overcome my shame of actively wanting more queer friends and made me take the first trembling steps to a support group. I don’t know how to express the utter relief that came with being able to do these without berating myself for “asking for too much”. I wish there was an easy way to explain to the world that wanting intimacy isn’t shameful, to tell my mother that my lovers are as important to me as family, and that Tinder is my favourite place sometimes. I’ve never been ashamed of being queer, but the moral obligation we attach to queer persons – expecting them to change the world and explain themselves to everyone else, or to present themselves as trophies for assimilation – made me craft an image for myself that made it easy to ignore my desires and let in shame. When I realised I was queer, I learnt the language of identity politics not just to find myself in it but also because I felt I’d never be accepted into the queer community without it. But somewhere it failed me, because it allowed me to hide my innermost desires for love and intimacy behind it. While I owe identity politics a lot, and I understand the need to define yourself within it, I still hope every queer person finds that peace that comes with acknowledging yourself as a person with love and desire like everyone else. In a world bent on politicising and othering us, even if only with the goal of ‘acceptance’, it helps to give yourself that space.It's still hard, but I'm learning to do things like hold my girlfriend's hand at Marine Drive without feeling weird, being comfortable being cheesy, and not judging people for being the same. I'm learning to prioritise love. I have always been told that family and work is priority and love is secondhand maal. That I'm a lesser person for wanting it. But I am unlearning. I am far more comfortable with hickeys showing and living peacefully in my private life without theorising too much about it or turning it into another queer art project. I guess I am now getting better at being a quieter queer.Earlier, I used to see queer people who were just living their lives without making too much of a hoo-haa about their identity and felt annoyed by them. I thought they weren't doing their duty by not being political about it. But lately when I see such people, I feel a reassurance and a certain liberation. To be reminded that whatever my identity is, I am at the end of the day a person like everyone else.

I’ve never been ashamed of being queer, but the moral obligation we attach to queer persons – expecting them to change the world and explain themselves to everyone else, or to present themselves as trophies for assimilation – made me craft an image for myself that made it easy to ignore my desires and let in shame. When I realised I was queer, I learnt the language of identity politics not just to find myself in it but also because I felt I’d never be accepted into the queer community without it. But somewhere it failed me, because it allowed me to hide my innermost desires for love and intimacy behind it. While I owe identity politics a lot, and I understand the need to define yourself within it, I still hope every queer person finds that peace that comes with acknowledging yourself as a person with love and desire like everyone else. In a world bent on politicising and othering us, even if only with the goal of ‘acceptance’, it helps to give yourself that space.It's still hard, but I'm learning to do things like hold my girlfriend's hand at Marine Drive without feeling weird, being comfortable being cheesy, and not judging people for being the same. I'm learning to prioritise love. I have always been told that family and work is priority and love is secondhand maal. That I'm a lesser person for wanting it. But I am unlearning. I am far more comfortable with hickeys showing and living peacefully in my private life without theorising too much about it or turning it into another queer art project. I guess I am now getting better at being a quieter queer.Earlier, I used to see queer people who were just living their lives without making too much of a hoo-haa about their identity and felt annoyed by them. I thought they weren't doing their duty by not being political about it. But lately when I see such people, I feel a reassurance and a certain liberation. To be reminded that whatever my identity is, I am at the end of the day a person like everyone else.

It is little-known among those in my circle that I serially crushed on boys (one per year) upto Class 8. Maybe it’s because after the last boy I liked, I realised I was queer. And when you’re queer, your story always begins from the moment you knew you were gay. From the moment you identified yourself as something different. As someone whose ability to desire and love required a label to be explained to everyone else. What was my sexuality before I knew? I don’t know – and it seems no one is really curious.

It is little-known among those in my circle that I serially crushed on boys (one per year) upto Class 8. Maybe it’s because after the last boy I liked, I realised I was queer. And when you’re queer, your story always begins from the moment you knew you were gay. From the moment you identified yourself as something different. As someone whose ability to desire and love required a label to be explained to everyone else. What was my sexuality before I knew? I don’t know – and it seems no one is really curious. I knew I was queer at different points in my life with different degrees of clarity. In 8th grade, when my heart did a somersault instead of the usual dhadko-fying when my Woman-Crush-Wednesday friend I was obsessed with sent me a text saying “I wish you were here”, I was at 10% “Knew I Was Gay (KIWG)”. When I googled bisexual and felt like, “Whoa, I can love love my friend?” I was at 20% but-in-denial KIWG. When in Class12 a girl told me she was a lesbian and I, ahem, promptly fell for her, I peaked at a 90% shit-ye-toh-real-ho-gaya KIWG.

I knew I was queer at different points in my life with different degrees of clarity. In 8th grade, when my heart did a somersault instead of the usual dhadko-fying when my Woman-Crush-Wednesday friend I was obsessed with sent me a text saying “I wish you were here”, I was at 10% “Knew I Was Gay (KIWG)”. When I googled bisexual and felt like, “Whoa, I can love love my friend?” I was at 20% but-in-denial KIWG. When in Class12 a girl told me she was a lesbian and I, ahem, promptly fell for her, I peaked at a 90% shit-ye-toh-real-ho-gaya KIWG. Thing is, I knew about LGBT rights and considered myself an ally very early. Before I even knew I was queer, I knew the term, the movement for their rights, the language of identity politics. I was already feministing, and when people called my best friend ‘corrupt’ (a word used generously in middle school) for having too many friends who were boys, I could call it “slut-shaming”. It was that time in my life when these words for experiences felt like they were liberating me. So when I finally knew I was gay, was I happy to have an identity that held some socio-political significance? A little I guess. It did make me feel a bit like a krantikari. But soon I just got really really confused.

Thing is, I knew about LGBT rights and considered myself an ally very early. Before I even knew I was queer, I knew the term, the movement for their rights, the language of identity politics. I was already feministing, and when people called my best friend ‘corrupt’ (a word used generously in middle school) for having too many friends who were boys, I could call it “slut-shaming”. It was that time in my life when these words for experiences felt like they were liberating me. So when I finally knew I was gay, was I happy to have an identity that held some socio-political significance? A little I guess. It did make me feel a bit like a krantikari. But soon I just got really really confused. Was I bisexual? But I hadn’t liked guys in years by then. Was I *gasp* a homoromantic heterosexual? I seemed to fall in love with women more than lust after them. Lesbian? But what about that dirty history of light-eyed boys I had crushes on? Who’d believe me if I said lesbian? This yo-yoing between labels stopped only when I realised I could call myself queer and leave it at that. And yet – that finding of the perfect word never really stopped. Many labels have knocked at my door ever since. Gender-fluid. Asexual. Demi-sexual. Anorgasmic. Sensual-sexual (my invention). Woman. Lesbian pays a monthly visit, I swear. And in moments of sheer terror, Actually Straight (You’re Just Faking It) comes says hi. For a year or so before I entered college, every second thought was about this, occupying my mental space much more than I’d expected. I thought I was obsessed. In that time somewhere in that relentless negotiation of determining who I was, I left behind my ability to fall in love or desire without the baggage of my queer identity. I pretend that the era of liking boys is irrelevant but perhaps it was the only time my sexuality was really just mine. Not a part of a larger discourse. Not different. Not relevant to anything or anyone but myself.

Was I bisexual? But I hadn’t liked guys in years by then. Was I *gasp* a homoromantic heterosexual? I seemed to fall in love with women more than lust after them. Lesbian? But what about that dirty history of light-eyed boys I had crushes on? Who’d believe me if I said lesbian? This yo-yoing between labels stopped only when I realised I could call myself queer and leave it at that. And yet – that finding of the perfect word never really stopped. Many labels have knocked at my door ever since. Gender-fluid. Asexual. Demi-sexual. Anorgasmic. Sensual-sexual (my invention). Woman. Lesbian pays a monthly visit, I swear. And in moments of sheer terror, Actually Straight (You’re Just Faking It) comes says hi. For a year or so before I entered college, every second thought was about this, occupying my mental space much more than I’d expected. I thought I was obsessed. In that time somewhere in that relentless negotiation of determining who I was, I left behind my ability to fall in love or desire without the baggage of my queer identity. I pretend that the era of liking boys is irrelevant but perhaps it was the only time my sexuality was really just mine. Not a part of a larger discourse. Not different. Not relevant to anything or anyone but myself. When I went to college, I was starting to know who I was. Although if I have to phrase it more honestly, I was starting to get better at explaining what I identified as. I started coming out to people and found solace in making queer art that further cemented me in people’s eyes as that Queer person. My work really was my refuge. While I was falling in love with close friends who were straight, roommates, beautiful seniors (basically everyone, the emotional ho that I was), I’d try to find answers through my work. When I was confused about why I sucked at understanding romance or approaching it, I analysed my queerness to death and made an animation that explained how heterosexuals had unlimited media to guide them in their love life, but us queers had nothing to teach us. When I was heartbroken and no politics could explain it, I would draw, and dump it in my Instagram. I’m still mentioned in some articles as a queer Insta artist (I call myself gay Rupi Kaur in private).

When I went to college, I was starting to know who I was. Although if I have to phrase it more honestly, I was starting to get better at explaining what I identified as. I started coming out to people and found solace in making queer art that further cemented me in people’s eyes as that Queer person. My work really was my refuge. While I was falling in love with close friends who were straight, roommates, beautiful seniors (basically everyone, the emotional ho that I was), I’d try to find answers through my work. When I was confused about why I sucked at understanding romance or approaching it, I analysed my queerness to death and made an animation that explained how heterosexuals had unlimited media to guide them in their love life, but us queers had nothing to teach us. When I was heartbroken and no politics could explain it, I would draw, and dump it in my Instagram. I’m still mentioned in some articles as a queer Insta artist (I call myself gay Rupi Kaur in private). My personal would always be political. So I took advantage of it and made a portfolio out of it. I was building a reputation as that Queer person, as that Queer artist, among my friends as that relentlessly gay friend. In truth just as a person, I had no clue how to navigate my love and sex life. I had placed all my value in making my identity useful – in changing the world, in articulating a politics, and I always prioritised it over (or perhaps even interchanged it with) my actual personal life. I was out and proud, but inside I found myself unexpectedly stumbling upon shame more and more. That shame though, was not about being queer.

My personal would always be political. So I took advantage of it and made a portfolio out of it. I was building a reputation as that Queer person, as that Queer artist, among my friends as that relentlessly gay friend. In truth just as a person, I had no clue how to navigate my love and sex life. I had placed all my value in making my identity useful – in changing the world, in articulating a politics, and I always prioritised it over (or perhaps even interchanged it with) my actual personal life. I was out and proud, but inside I found myself unexpectedly stumbling upon shame more and more. That shame though, was not about being queer. The better half of every ‘It Gets Better’ narrative starts with coming out. I had already done that. I already knew that liking, loving, desiring women was okay. But my personal life still felt...deeply sad. Whenever I fell for someone, the impossibility of it all would fall like a great weight on me. I was afraid of falling in love, because every time the person was either straight or not interested in me. I taught myself to confess my feelings but only did it when I was already in too deep. I didn’t know how to flirt or test the waters with someone because I was at a stage where just the prospect of befriending a queer person itself would freak me out, forget expressing romantic or sexual interest in them. In college we were surrounded by romancing and sexing and hormones flying around. But I felt completely in the dark about how sexual interactions happened, let alone know how to engage in them myself.

The better half of every ‘It Gets Better’ narrative starts with coming out. I had already done that. I already knew that liking, loving, desiring women was okay. But my personal life still felt...deeply sad. Whenever I fell for someone, the impossibility of it all would fall like a great weight on me. I was afraid of falling in love, because every time the person was either straight or not interested in me. I taught myself to confess my feelings but only did it when I was already in too deep. I didn’t know how to flirt or test the waters with someone because I was at a stage where just the prospect of befriending a queer person itself would freak me out, forget expressing romantic or sexual interest in them. In college we were surrounded by romancing and sexing and hormones flying around. But I felt completely in the dark about how sexual interactions happened, let alone know how to engage in them myself. I think I never was able to spot a queer person and just befriend them because somewhere I had convinced myself that if I was in a supportive environment, who was I to ask for more? I felt silly for wanting a community, wanting to seek out more queer people, for being single and utterly inexperienced in my personal life in spite of being in a liberal art school where according to other Bangaloreans, “every second person is bisexual”. If there was a word for cruising for queer women, I would have sucked at it. Whenever I went to queer events, the utter confidence with which people oozed sexuality or openly flirted with each other only served to reinforce my insecurities, because I just didn’t know how to get there. I was ashamed of struggling with my sexuality long after having done the entire I’m Out and Proud thing. I guess what I didn’t realise was that more than anything else, I was struggling with being sexual, not homosexual. Which may not be different from anyone else, but for a queer person when that struggle is reduced to ‘coming out’ or ‘being accepted’, and personal goalposts are all about resisting prejudice, it leaves out a big part of ‘love learning’ – of learning to love, to desire, and having a love and sex life.

I think I never was able to spot a queer person and just befriend them because somewhere I had convinced myself that if I was in a supportive environment, who was I to ask for more? I felt silly for wanting a community, wanting to seek out more queer people, for being single and utterly inexperienced in my personal life in spite of being in a liberal art school where according to other Bangaloreans, “every second person is bisexual”. If there was a word for cruising for queer women, I would have sucked at it. Whenever I went to queer events, the utter confidence with which people oozed sexuality or openly flirted with each other only served to reinforce my insecurities, because I just didn’t know how to get there. I was ashamed of struggling with my sexuality long after having done the entire I’m Out and Proud thing. I guess what I didn’t realise was that more than anything else, I was struggling with being sexual, not homosexual. Which may not be different from anyone else, but for a queer person when that struggle is reduced to ‘coming out’ or ‘being accepted’, and personal goalposts are all about resisting prejudice, it leaves out a big part of ‘love learning’ – of learning to love, to desire, and having a love and sex life. I used to try to find the answers to all my struggles in my queerness and to some extent it did help to be reassured that, yes, it was more difficult to find love as a queer person because – statistical odds, haha, and that, yes, I didn’t get any training from real life or media on dating as a queer woman. But this ended up blinding me to something more fundamental: that a lot of my insecurities stemmed from sexual shame, not necessarily because I was queer.

I used to try to find the answers to all my struggles in my queerness and to some extent it did help to be reassured that, yes, it was more difficult to find love as a queer person because – statistical odds, haha, and that, yes, I didn’t get any training from real life or media on dating as a queer woman. But this ended up blinding me to something more fundamental: that a lot of my insecurities stemmed from sexual shame, not necessarily because I was queer. I may have discovered myself straightaway in identity politics (and I am truly glad I skipped the “Oh shit I’m an abomination this isn’t normal” phase), but my identity as a queer person soon became a bit of a shield to protect myself from the turbulence that comes with one’s private life, in the world of love, in the world of sex. I didn’t take my steps into these worlds because it got easy to foreground my queerness and ignore the fact that I wanted love and sex as a person, not for the sake of ideology. And somewhere it was easy to ignore it, because I have in many ways been taught to think of relationships and sex as an indulgent and unimportant. It was easier to say I was queer and think it was socially and politically relevant, than to say I was queer and I wanted to know more people like me to befriend or date. Even when I tried to create a safe space in college, my first fear was, “What if people think I’m doing this just to find people to date?” To be seen as wanting love and pleasure at the most basic human level – that’s an emotional shame no one seemed to be talking about. Even the most woke of people around me would never be caught dead admitting to actively looking for intimacy (ahem ahem, Tinder shamers). To admit to being lonely was to let down ‘the cause’.

I may have discovered myself straightaway in identity politics (and I am truly glad I skipped the “Oh shit I’m an abomination this isn’t normal” phase), but my identity as a queer person soon became a bit of a shield to protect myself from the turbulence that comes with one’s private life, in the world of love, in the world of sex. I didn’t take my steps into these worlds because it got easy to foreground my queerness and ignore the fact that I wanted love and sex as a person, not for the sake of ideology. And somewhere it was easy to ignore it, because I have in many ways been taught to think of relationships and sex as an indulgent and unimportant. It was easier to say I was queer and think it was socially and politically relevant, than to say I was queer and I wanted to know more people like me to befriend or date. Even when I tried to create a safe space in college, my first fear was, “What if people think I’m doing this just to find people to date?” To be seen as wanting love and pleasure at the most basic human level – that’s an emotional shame no one seemed to be talking about. Even the most woke of people around me would never be caught dead admitting to actively looking for intimacy (ahem ahem, Tinder shamers). To admit to being lonely was to let down ‘the cause’. I think my turning point for acknowledging and dealing with this shame firsthand happened when I joined Tinder. I owe Tinder-Bhai a lot. It was my first and best wingman and pushed me to do what I desired in my private life more than anyone else. I did get some flak because of it because not many around me really took Tinder seriously. I first got on it during an exchange programme because it was so far away from home. I even managed to bring my date over for dinner at my dorm, and overcame that fear of being seen as a sexual dating being. Back in India it took some time and (yet another) glorious heartbreak to push me back into the dating world. Tinder allowed me to see myself as a queer being, but through a more personal lens. I sexted for the first time. Went on dates. Learnt to gauge and express interest. Sent pictures of the moon. Talked. Talked a lot. I not only started learning how people find sexual or romantic partners, but also ended up meeting a lot of queer women I had these personal conversations with, conversations I never realised I needed to have. Tinder made me overcome my shame of actively wanting more queer friends and made me take the first trembling steps to a support group. I don’t know how to express the utter relief that came with being able to do these without berating myself for “asking for too much”. I wish there was an easy way to explain to the world that wanting intimacy isn’t shameful, to tell my mother that my lovers are as important to me as family, and that Tinder is my favourite place sometimes.

I think my turning point for acknowledging and dealing with this shame firsthand happened when I joined Tinder. I owe Tinder-Bhai a lot. It was my first and best wingman and pushed me to do what I desired in my private life more than anyone else. I did get some flak because of it because not many around me really took Tinder seriously. I first got on it during an exchange programme because it was so far away from home. I even managed to bring my date over for dinner at my dorm, and overcame that fear of being seen as a sexual dating being. Back in India it took some time and (yet another) glorious heartbreak to push me back into the dating world. Tinder allowed me to see myself as a queer being, but through a more personal lens. I sexted for the first time. Went on dates. Learnt to gauge and express interest. Sent pictures of the moon. Talked. Talked a lot. I not only started learning how people find sexual or romantic partners, but also ended up meeting a lot of queer women I had these personal conversations with, conversations I never realised I needed to have. Tinder made me overcome my shame of actively wanting more queer friends and made me take the first trembling steps to a support group. I don’t know how to express the utter relief that came with being able to do these without berating myself for “asking for too much”. I wish there was an easy way to explain to the world that wanting intimacy isn’t shameful, to tell my mother that my lovers are as important to me as family, and that Tinder is my favourite place sometimes. I’ve never been ashamed of being queer, but the moral obligation we attach to queer persons – expecting them to change the world and explain themselves to everyone else, or to present themselves as trophies for assimilation – made me craft an image for myself that made it easy to ignore my desires and let in shame. When I realised I was queer, I learnt the language of identity politics not just to find myself in it but also because I felt I’d never be accepted into the queer community without it. But somewhere it failed me, because it allowed me to hide my innermost desires for love and intimacy behind it. While I owe identity politics a lot, and I understand the need to define yourself within it, I still hope every queer person finds that peace that comes with acknowledging yourself as a person with love and desire like everyone else. In a world bent on politicising and othering us, even if only with the goal of ‘acceptance’, it helps to give yourself that space.It's still hard, but I'm learning to do things like hold my girlfriend's hand at Marine Drive without feeling weird, being comfortable being cheesy, and not judging people for being the same. I'm learning to prioritise love. I have always been told that family and work is priority and love is secondhand maal. That I'm a lesser person for wanting it. But I am unlearning. I am far more comfortable with hickeys showing and living peacefully in my private life without theorising too much about it or turning it into another queer art project. I guess I am now getting better at being a quieter queer.Earlier, I used to see queer people who were just living their lives without making too much of a hoo-haa about their identity and felt annoyed by them. I thought they weren't doing their duty by not being political about it. But lately when I see such people, I feel a reassurance and a certain liberation. To be reminded that whatever my identity is, I am at the end of the day a person like everyone else.

I’ve never been ashamed of being queer, but the moral obligation we attach to queer persons – expecting them to change the world and explain themselves to everyone else, or to present themselves as trophies for assimilation – made me craft an image for myself that made it easy to ignore my desires and let in shame. When I realised I was queer, I learnt the language of identity politics not just to find myself in it but also because I felt I’d never be accepted into the queer community without it. But somewhere it failed me, because it allowed me to hide my innermost desires for love and intimacy behind it. While I owe identity politics a lot, and I understand the need to define yourself within it, I still hope every queer person finds that peace that comes with acknowledging yourself as a person with love and desire like everyone else. In a world bent on politicising and othering us, even if only with the goal of ‘acceptance’, it helps to give yourself that space.It's still hard, but I'm learning to do things like hold my girlfriend's hand at Marine Drive without feeling weird, being comfortable being cheesy, and not judging people for being the same. I'm learning to prioritise love. I have always been told that family and work is priority and love is secondhand maal. That I'm a lesser person for wanting it. But I am unlearning. I am far more comfortable with hickeys showing and living peacefully in my private life without theorising too much about it or turning it into another queer art project. I guess I am now getting better at being a quieter queer.Earlier, I used to see queer people who were just living their lives without making too much of a hoo-haa about their identity and felt annoyed by them. I thought they weren't doing their duty by not being political about it. But lately when I see such people, I feel a reassurance and a certain liberation. To be reminded that whatever my identity is, I am at the end of the day a person like everyone else.