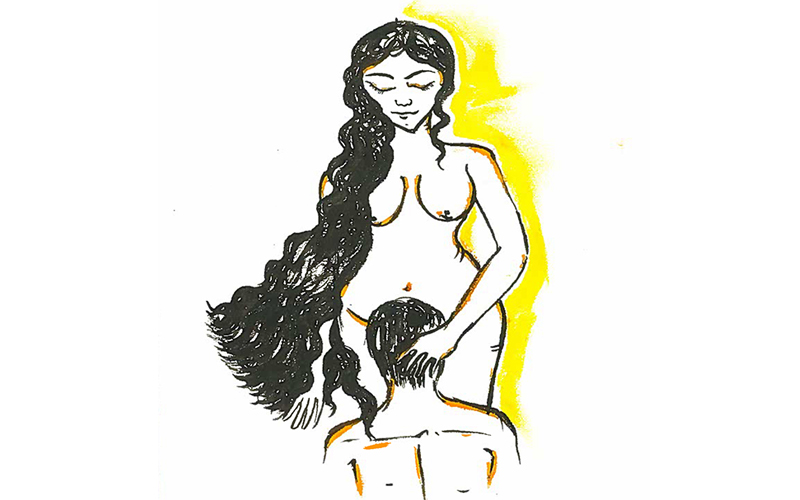

I was born on July 12, 1984. My birth story is nothing less than amazing. My mother survived the tedious, 12-hour labour and, contrary to how other babies are born, with the back of their heads descending from the womb and out the birth canal, I was born from my mother’s birth canal face first.

Also, mysteriously, the umbilical cord was tied to my face. That became the genesis of my facial deformity. The obstetrician had to maneuver my positioning in order to avoid contact of the umbilical cord fluids with my eyes, and prevent the fluids from concentrating and tightening around my head—both of which could have had a devastating effect on me. It would have left me with either a permanent disability in vision (blindness) or some terrible head disorder.

Instead, I have a facial deformity that has left one side of my face swollen.

Since the beginning, I have had many consultations with both traditional and modern approaches to medicine. My peculiar birth story somehow made the traditional stories more convincing. Visiting mediums became my parents’ routine.

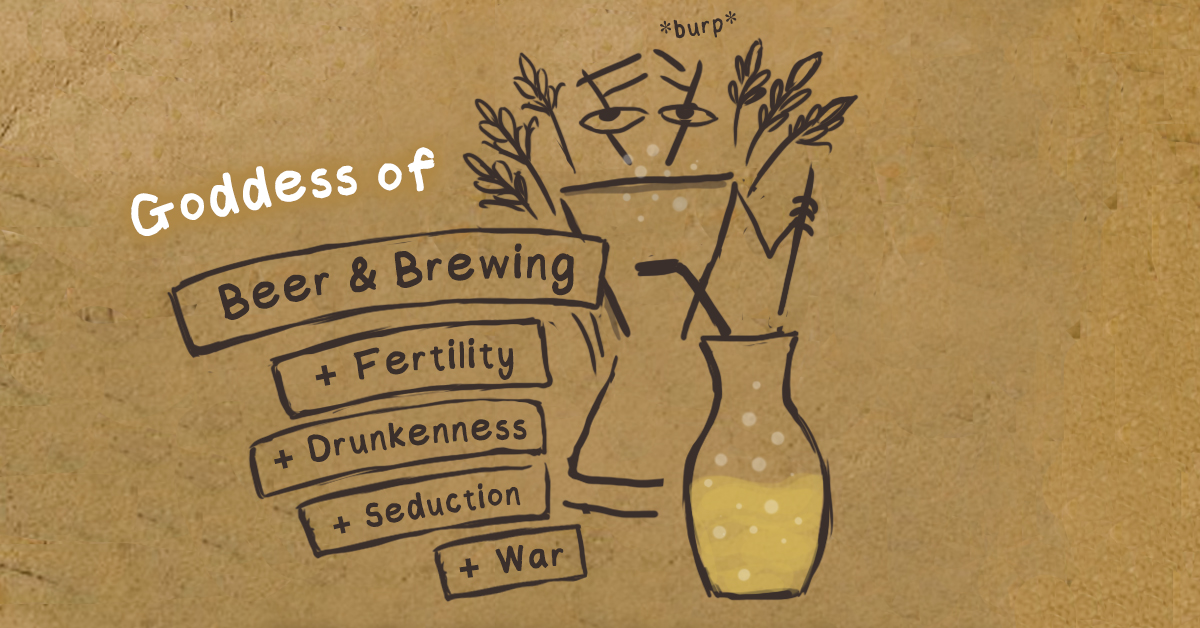

In Africa, whenever such a situation arises, the need for ‘seeing’ or ‘checking’, as it is called, becomes imperative. A traditional doctor—referred to as the ‘native doctor’—is saddled with the task of ‘checking’ or spiritually diagnosing the cause of the ailment and consequently prepares herbal medicines and gives instructions on usage.

My Christian background led my parents to visit several churches for prayers too for what was called ‘deliverance’. At the time, I was about three or four years old. From one native doctor to the other, one specialist health facility to another, one faith healer to another, I moved around to many places with my parents. All manner of substances as prescribed by the specialists were administered. I was three years old when I first had major facial surgery.

After the successful completion of the first surgical operation, that is, coming out of the theater alive, there was a need for a second major operation. I spent six months at the The Lagos Teaching Hospital (LUTH), where the first operation took place. I remember how my bed space was arranged. There was something like white Plaster of Paris tied all over my body, except for my eyes and nose. During that time, I was being fed through inserted pipes that passed through my nostrils. Not the best experience of my life! [how do you remember this?]

At the same hospital, I experienced my second surgical operation and the correction of the initial bandages and other healing elements—it was asserted that I eat fluid foods and live on the prescribed drugs for six months for the recuperation. According to what my father told me, years later, the management wanted to carry out subsequent minor operations. However, Dad refused, as he feared losing his son. The medical professionals assured my parents I would get better as I grew older. That the swollen side of my left cheek would witness a drastic ‘return to normal’. But that was not to be.

In the meanwhile, I would be at the receiving end of comments from the children in the neighbourhood. Some neigbours, kids and even adults, on seeing me come back to school after the surgery, would say, “Look at him with the big cheek, very swollen!’’

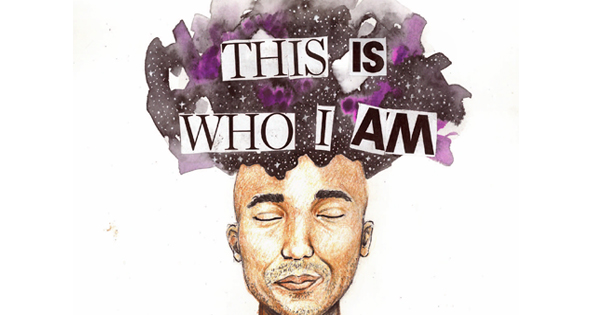

At six this felt humiliating and I felt isolated.

Though I was given the education my parents thought I deserved, care (with the help of house-help, as they were busy) and other material support, my experiences with peers, even school teachers and neighbors, left indelible marks on me—consciously and sub-consciously.

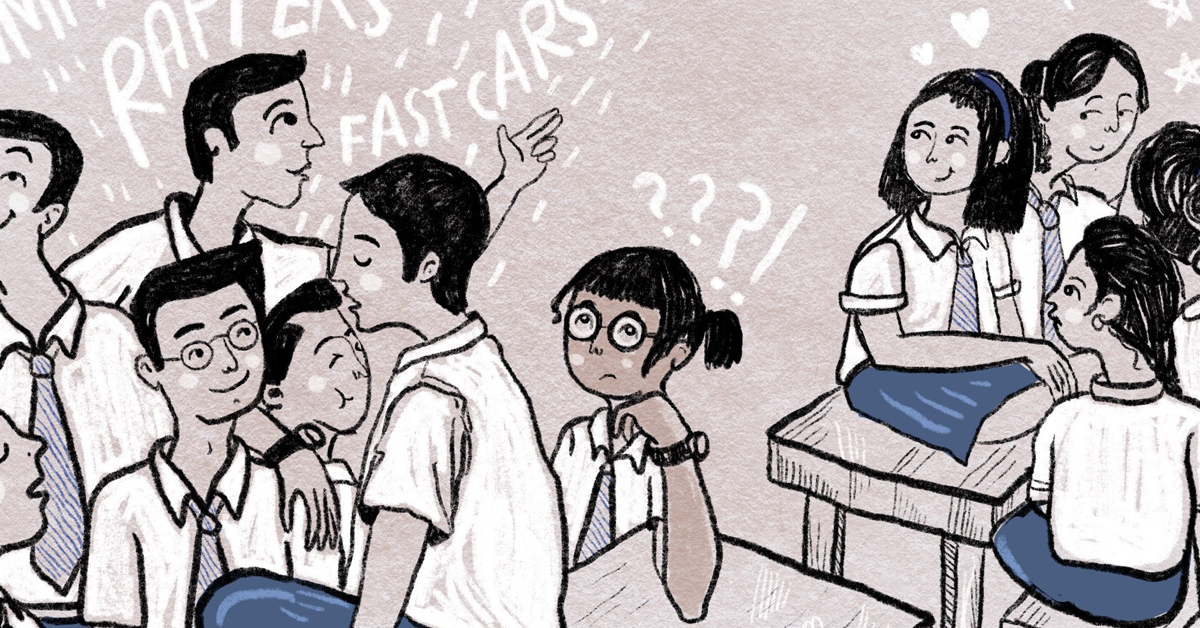

My childhood years were characterized by the bad and the ugly. I still remember a classmate in secondary school calling me ‘the big mouth guy’, right in the presence of a 20- pupil class. She made these remarks in the presence of our class teacher who did not seem to mind what she had said. The moment felt earth shattering to me and I swallowed my feelings of insult quietly.

I had no one to turn to for support. I had no friends to share my pains with. My parents were usually the busy type. I was raised partly under the tutelage of over 14 housemaids who didn’t understand what I was going through. They were all about business: doing all house duties as mandated and getting paid afterwards.

My mother later confessed to me that she and my dad thought I would grow up to be a dullard. All through my elementary school education, I struggled; the best I ever attained was a slightly-below average position. My promotion was like that of a camel passing through the eye of a needle!

The feat would always be achieved through consistent home coaching and after-school lessons—all arranged by my parents. To be candid, I didn’t take my schooling seriously throughout my elementary education.

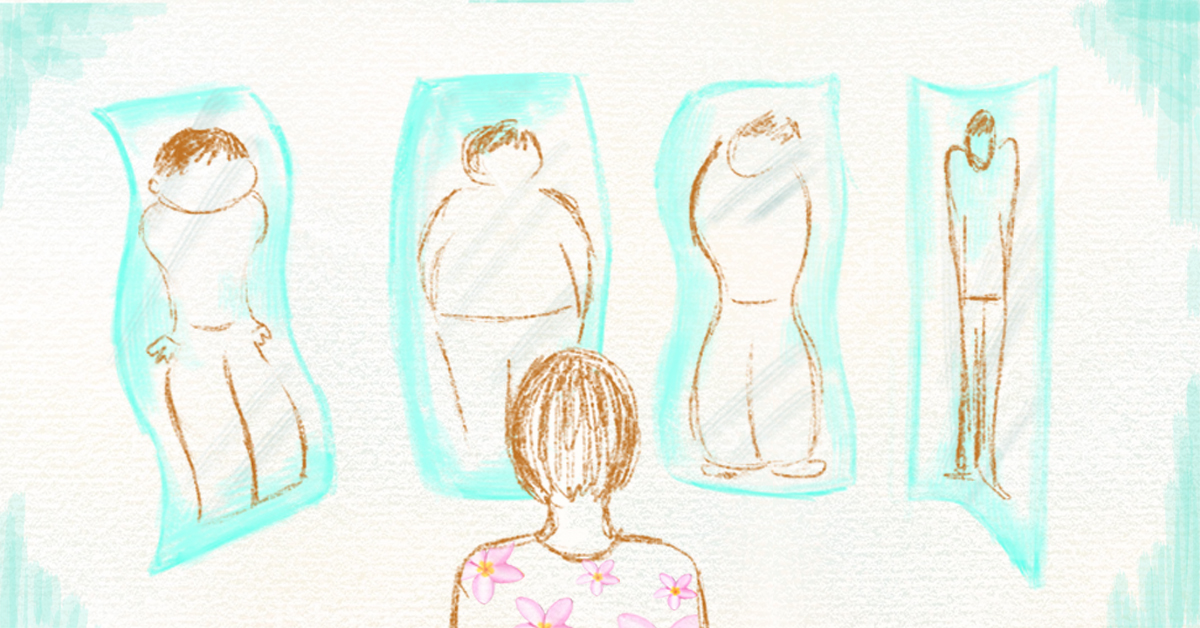

The psychological effects of living with a facial deformity were ever present. Staying alone, being unnecessarily shy and moody became my habits. My confidence dwindled over the years as my personality witnessed a plateau, compared to the mountains of my peers.

Sharing with the adults around me that I was insulted at the school wouldn’t help either. Their reply would be: “Don’t disturb me! The burden I am carrying is heavier than yours!”

It was terrible, and very disheartening. These repeated responses engendered a sense of aloneness. I had no one to confide in! And yet, being the first child, I had younger siblings looking up to me for inspiration…

My post-primary education saw me go through another phase of enduring the shame, degradation and humiliation of being around facially handsome and beautiful colleagues. Again, my parents, having the financial resources, sent me to what they thought was the best secondary school in Lagos, Nigeria. It was a privately-owned post-primary education outfit, There, I met students from diverse cultural and religious backgrounds. There, Idecided to take the bull by the horns and make friends (or at least talk mates. I eventually met two guys—Quadri and Emeka. They were quite understanding teenage men. They knew how to relate with me the best way they could, though they were far behind the brightest of students who couldn’t afford to talk to a facially deformed and an academically non-serious serious person like me.

Unfortunately, my friendship with Quadri and Emeka was shortlived. They both withdrew and left school at the second and third junior years respectively, due to family circumstances. They told me long before they left. And then I was in a world of my own. Interestingly, I started showing interest in my academics in my second junior year of secondary school. Till this day, I can’t fathom what caused this change or how I was able to transcend academic mediocrity to attain excellence in my studies. At that point, my academic skills attracted the company of handsome boys and beautiful girls—a dream-come-true experience.

But, they weren’t the friends I thought they ought to be; they actually ‘feasted’ on what I could offer—insight into the subject areas they found difficult to comprehend. To me, all I desired was company. After all, I believed it was better to be in the company of others than to be a loner. That became a way of coping with my deformity.

Meanwhile, I was finding it difficult to relate to my family on my facial deformity issue.

“Your swollen cheek will be a thing of the past as you grow older,” I had been assured.

This was when I was 14 years old.

I waited patiently for a time in my life when I could behold my face in the mirror and say, “the handsome me is here and has come to stay”.

“At what age do you think I’ll be facially alright?” I would ask curiously.

“Before long. I promise your face will be way better than it is now”.

But I needed a precise answer. “But what age do you think this will be?”

That’s when I received the biggest shock of my life!

“I don’t know! I’m not God” my Mother responded. It was a harsh one. I still remember.

“Okay.” I decided never to ask again.

As secondary school continued, I had more company come to me for assistance, not friendship. Yet, I was not perturbed; I was encouraged to do more for them. I was kept at arms length by girls I liked.

Mary was one who refused my relationship proposal We stood alone and had the following conversation.

Me: I’ve been looking forward to asking you something

Mary (curious): What do you mean?

Me (my heart beating faster): You know…I’ve been thinking about you.

Mary: Why think about me?

Me: I really want you.

Mary (chuckles): For what?

Me: A relationship (My hands holding hers).

Mary: I’m so sorry I can’t. I thought you wanted to call me for some kind of important chat (She looks at my face. I understand the body language).

Me: Okay. I’m sorry (shaking my head in utter disappointment).

Mary: I have to go (she lets go of my hand and walks away).

Me: Alright

I leave a disappointed man.

She was one of those beautiful girls who would come to me from time to time to help her with her Mathematics, a subject she was not good at. This continued until I completed my secondary schooling. Sadly, I couldn’t establish any form of intimate connection with her, all throughout my secondary school years. Until I was done with school, there were no other communication I had with her.

This was the first and last time I chased romance. There was no romance really after it. There was no conversation with Mary either.afterwards

In Nigeria, between 2001 and 2003, it was difficult to gain admission directly into university or even the polytechnic. After secondary school, unless parents or guardians knew ‘short-cuts’ to expedite the admission process, students were likely to spend years at home seeking admission into tertiary institutions. I finished secondary school in 2001, having excelled in my Senior studies.

I waited for two years before I sat for the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board to gain admission into university.

During this period at home, I joined my mother in her local business.

She traded in staple food items—rice, beans, cassava flakes, locally known as ‘garri’ and other things. It was yet another school of hard knocks. Customers would take a thorough look at my facial deformity and express compassion (audibly or in gestures). That didn’t help me at all, though I understood they meant well. I just had to learn to how to cope!

My parents’ financial resources were dwindling. Sixteen at the time, I knew things were not the way they used to be. Our standard of living had drastically declined. While at home during this period, I wondered if going overseas was the answer to my problems. Maybe other doctors or specialists could help with my facial deformity. Again, and against my inclination, I had to ‘open’ another conversation.

‘Do you know of anyone who would be able to handle my case? My left cheek is still swollen.” I asked my mother.

“I really have no idea!’ Was the reply. ‘And please, don’t ask me those questions! When you get into university and graduate, you can get a job and save your own money for treatment,” she answered. Bitterness was written over her face. My mother answered, more hasher than I’d have expected.

It was obvious that I was on my own. I approached various non-government organizations but my requests for help proved futile. I was never attended to!

I had to learn to be practical and cope with my deformity by tuning out from the negative things people would say, both to my face and behind my back. I have been on my own, in my childhood, youth and young adulthood. The scars remain.

I am trying to ensure that I remain healthy by taking more of organic foods, and ensuring I don’t over-think my current swollen-cheek predicament. I live with the moment as I press on, while taking my body just the way it is. After all, “such is life’’, they say.

Mr Ben, as he is fondly called, is a represented and published poet, playwright, essayist, children's author, novelist, lyricist, and voice over artiste. Based in Lagos, Nigeria, he delights in traveling, reading and meeting people.