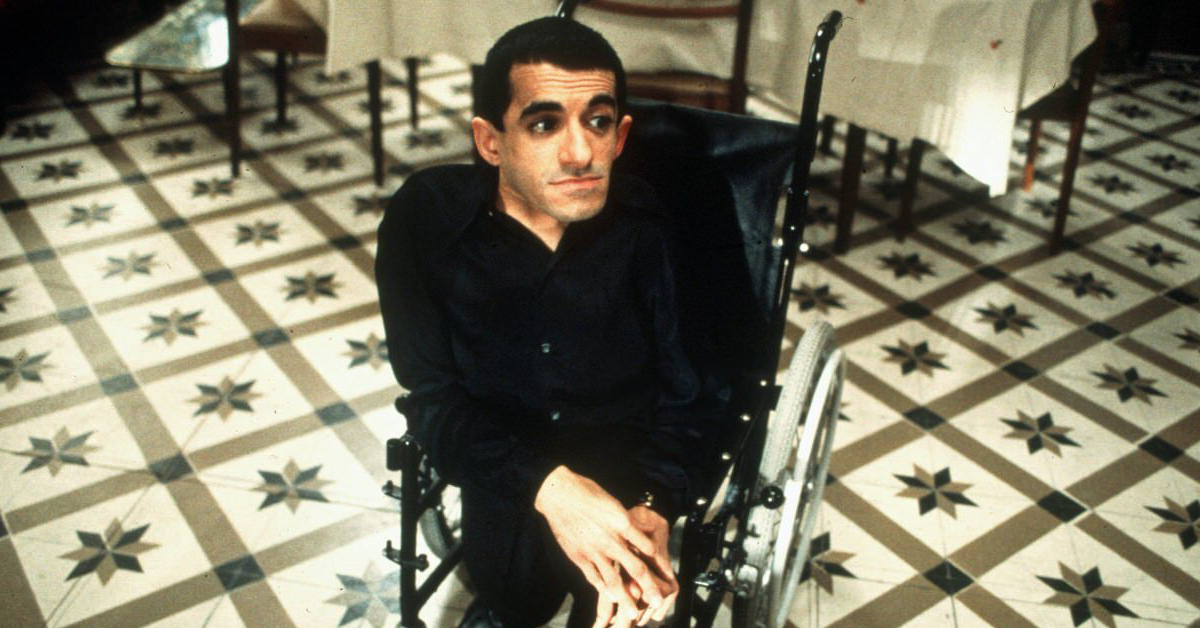

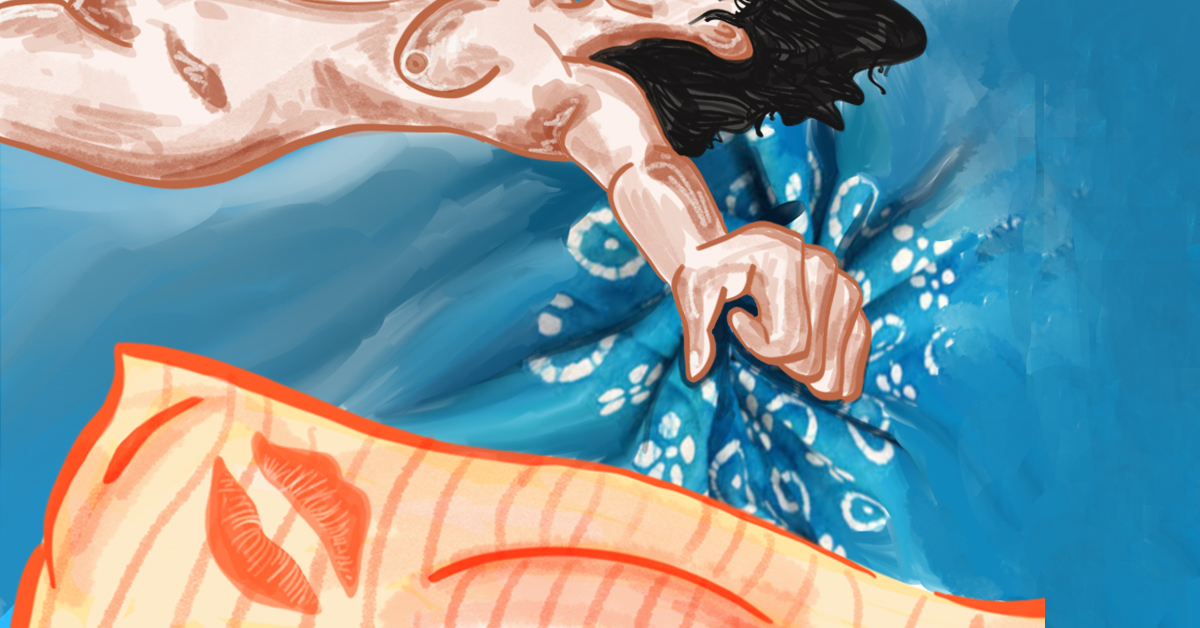

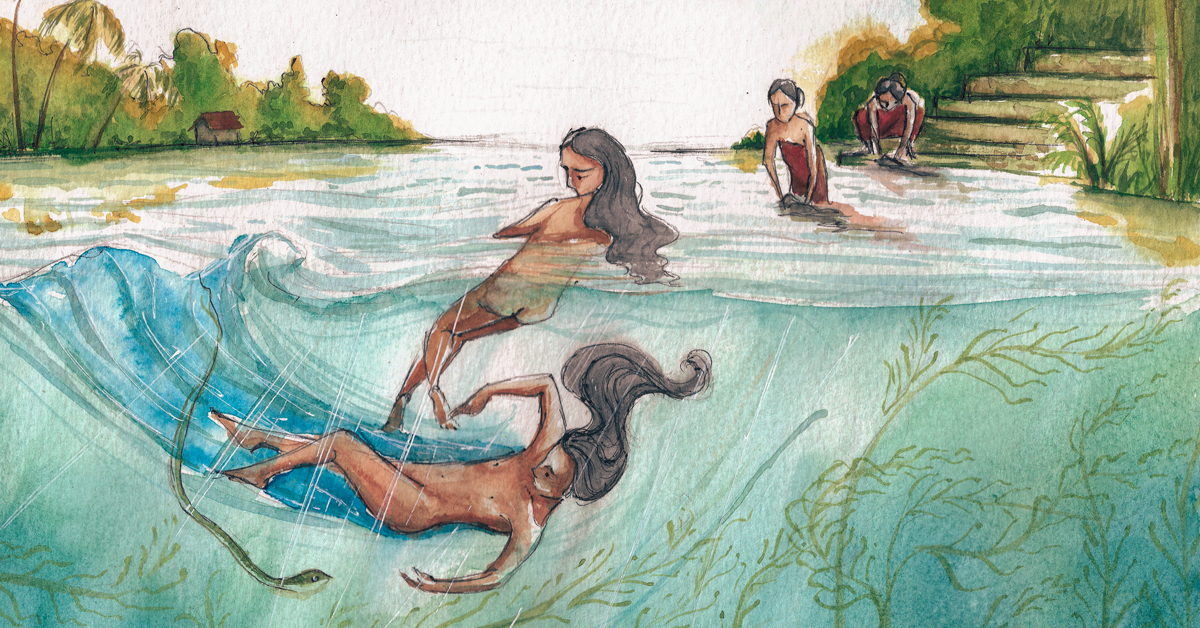

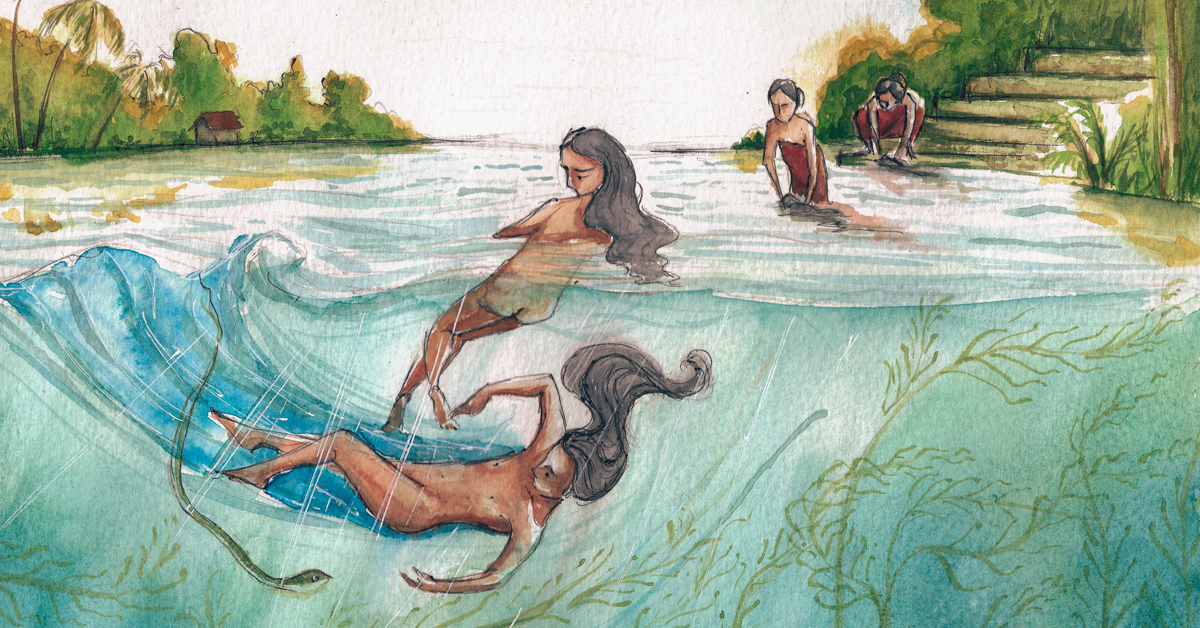

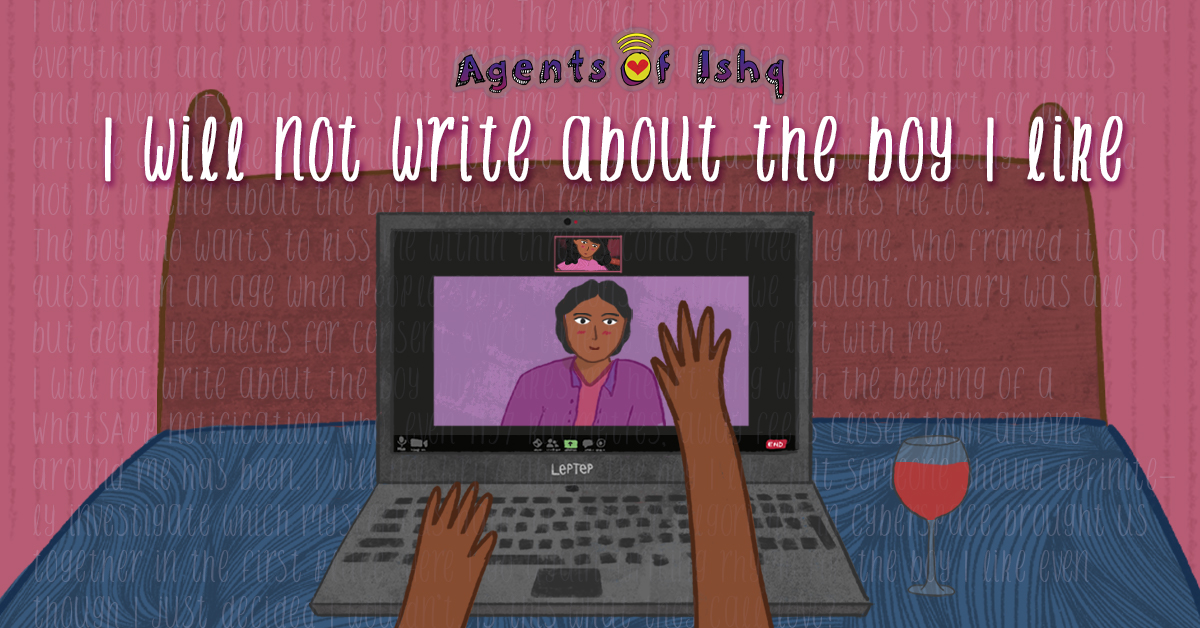

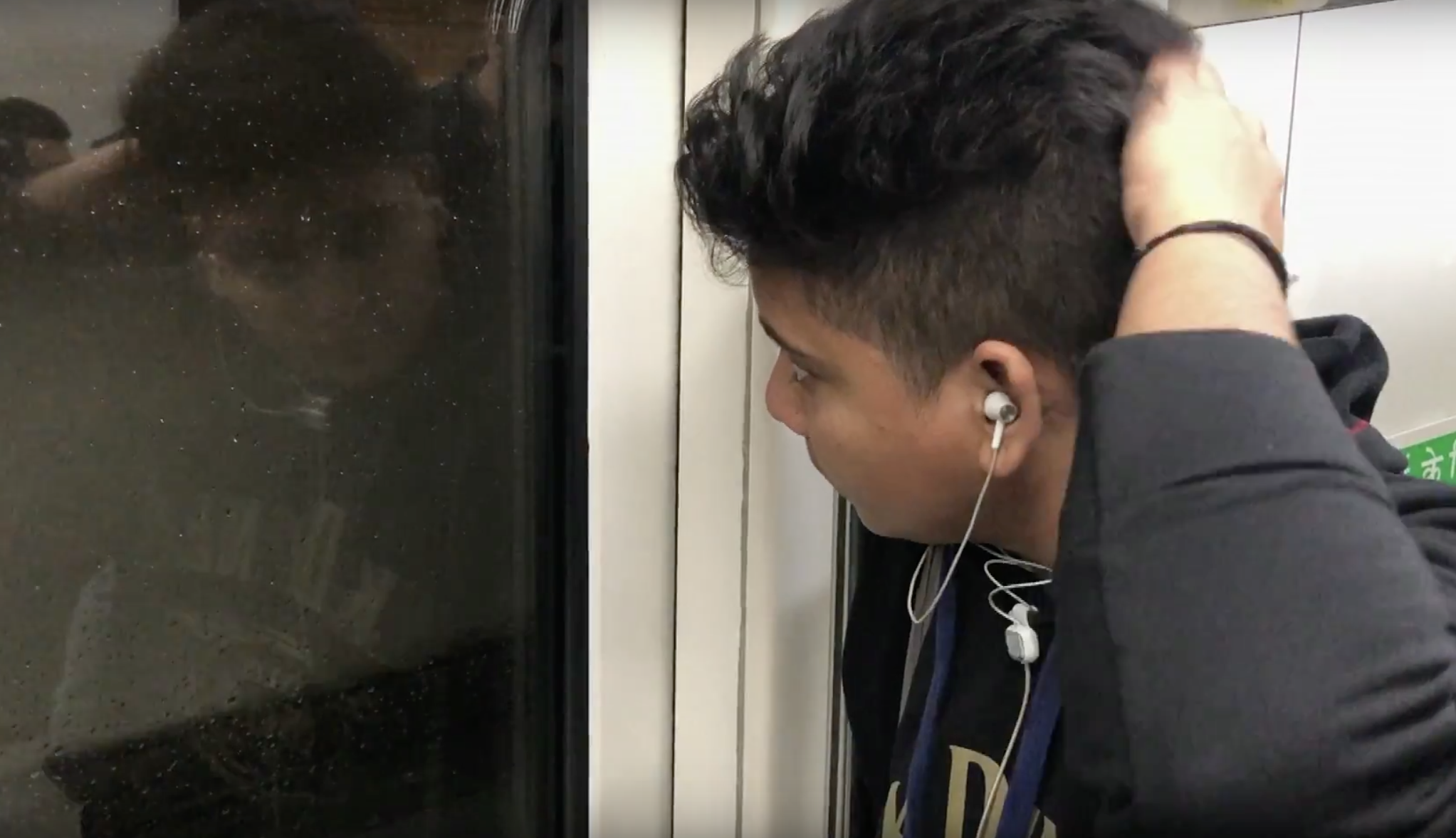

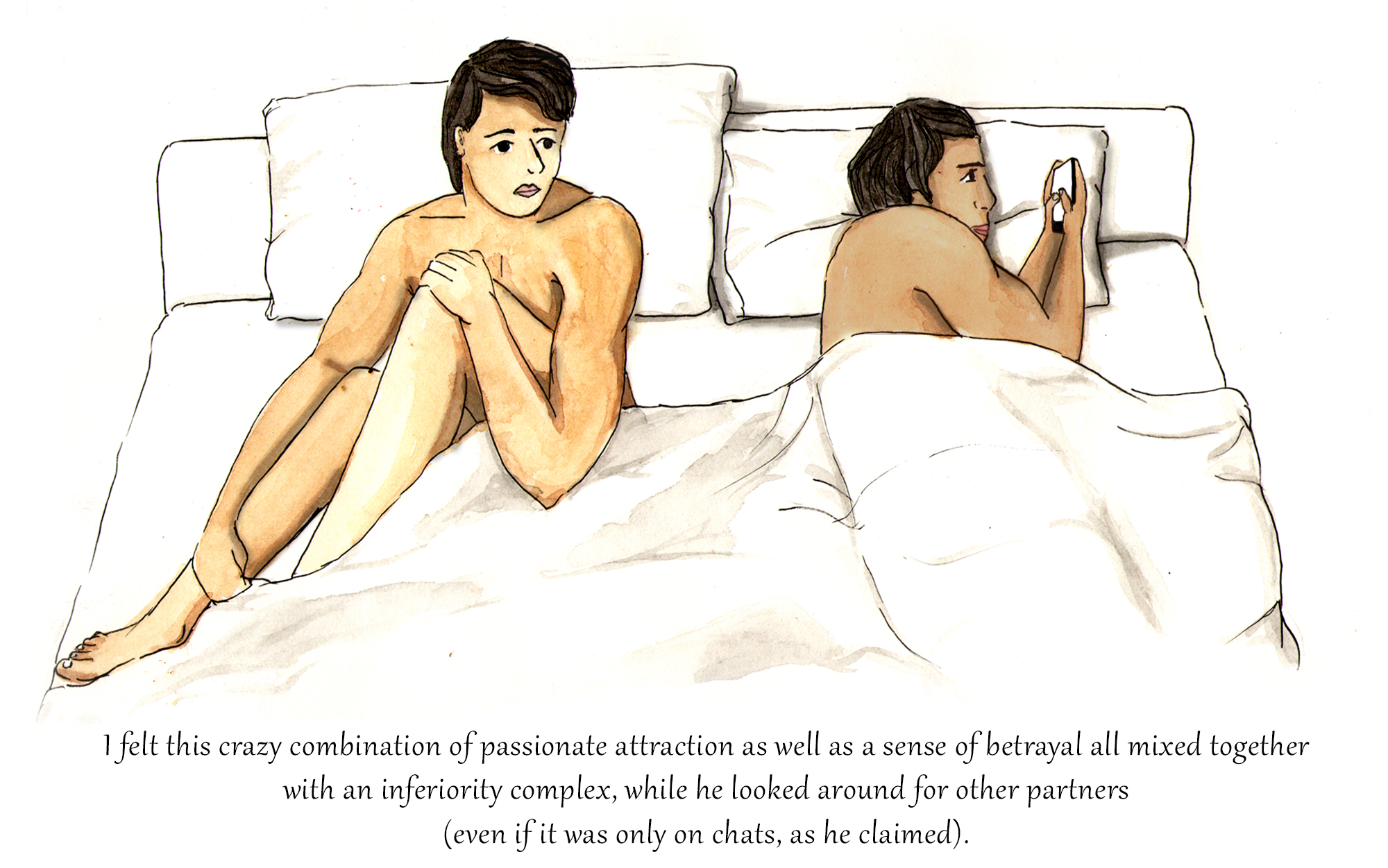

The afternoon light streamed into my hostel room. It was a golden summer in Manipal—ripe mangoes and gulmohar in bloom. Inside, The Half of It played on my laptop. Ellie and Aster swam, backs submerged, faces upturned, in a cliffside pool. There was something cinematic and erotic about their almost-temples-touching, circling silence.

I looked at them with narrowed eyes; my thoughts spinning out of control. Was there even a 1% chance that I could imagine myself as one of the characters?

I prayed that I wouldn’t be able to.

*

This was the first queer movie I had watched at J’s insistence. It had only been about six weeks since I’d moved away from home for the first time to the campus town of Manipal. The first one and a half years of our course had been online. Now, in our fourth semester, we had arrived with boriya-bistar to a foreign land amidst older students for whom Manipal was already home. It felt strange to be thrust into this space-time continuum where I was technically supposed to know everything, but felt as clueless as I had been during my first Zoom class.

Amidst all the quarantining chaos and my social anxiety, I became close friends with J and A, who were roommates and lived in the same hostel block. Living away from my parents for the first time and suddenly having to become an ‘adult’ felt daunting and lonely—the people around me spoke in an unfamiliar tongue and I got lost in the labyrinthine routes of campus. But it felt easier when I knew I had another room to go to, people to stress over assignments with, giggle and have deep conversations late into the night.

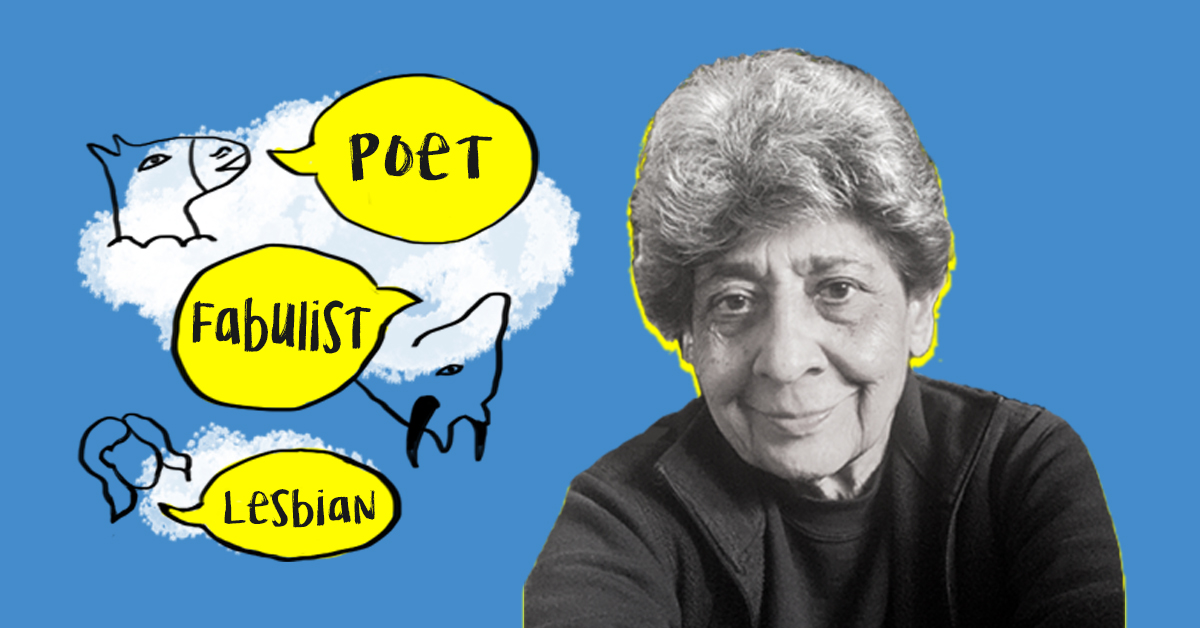

Amongst these midnight confession sessions and trauma-bonding circles, J talked about her queer awakening—how she had fallen for her straight (of course) best friend, how the unrequitedness had crippled her, and her journey with her identity.

I listened. This was the first time I was encountering queerness in flesh and blood, but there was nothing unfamiliar about her. To me, J was just another person. Brilliant, funny, kind and reliable. J talked about a growing distance between A and herself, how it was irritating to share the same space all the time, and how she was glad to have me. We grew close with a terrifying intensity, and exchanged secrets and joys and insecurities.

Having grown up in four different cities and schools, I’d never had a stable and sustained group of friends. What was the point of investing in someone when I would be uprooted again? To them, I was just a change in variable, they would forget me. For me, it was the upstaging of my entire equation.

I had never known friendship could feel like this.

And then, I felt something more.

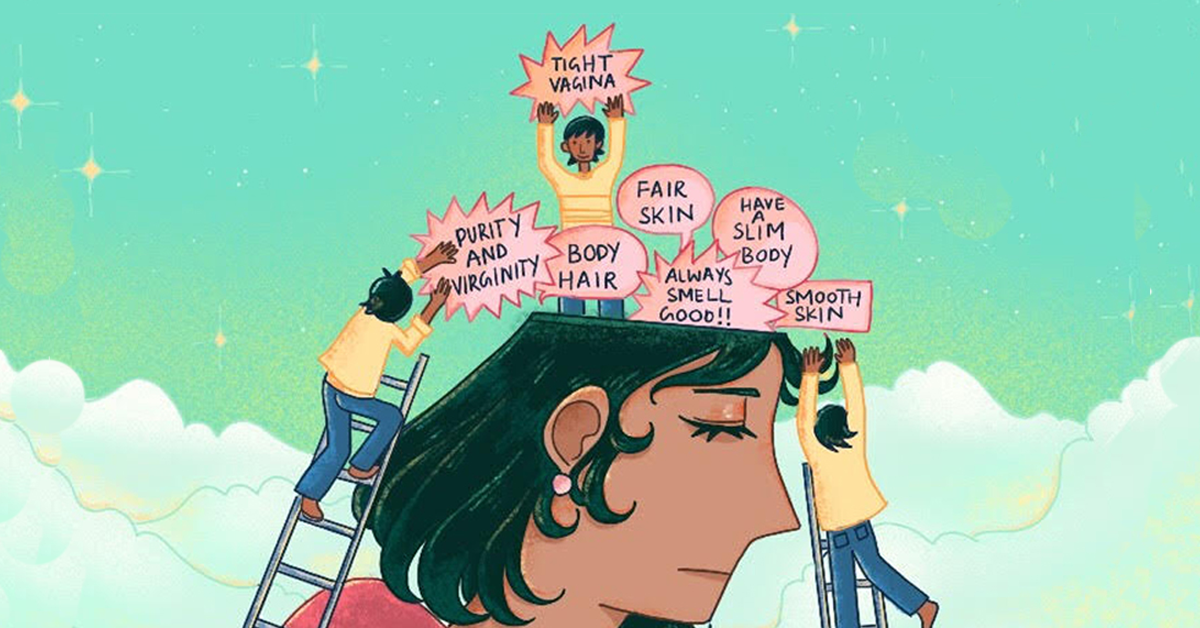

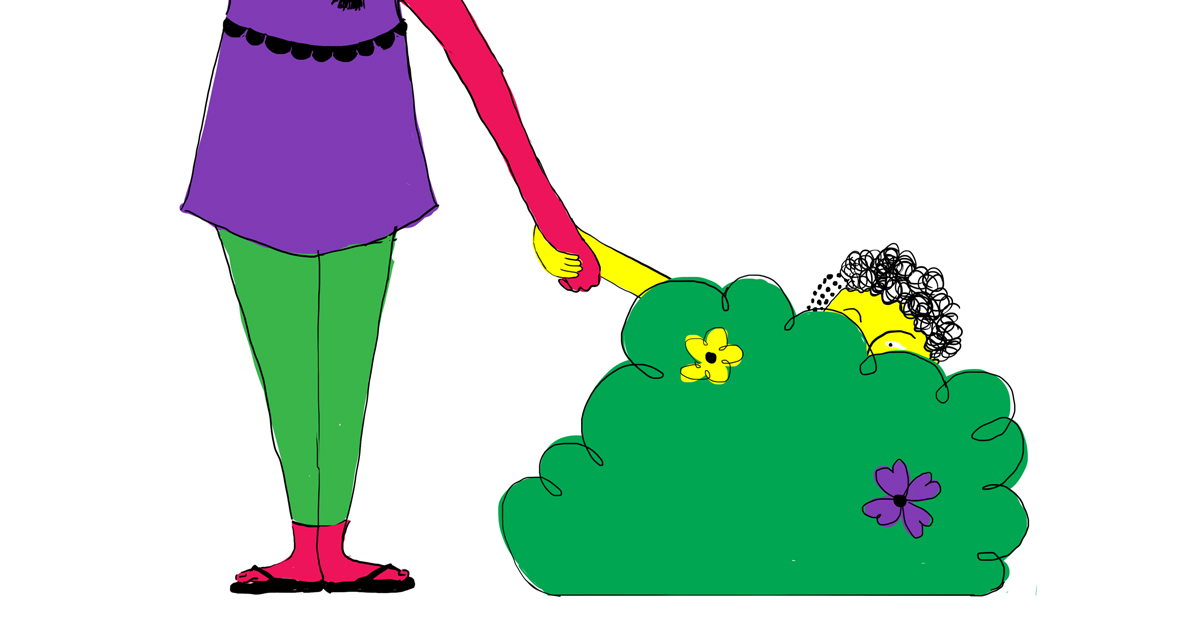

Suddenly, I was finding excuses to talk more to J, and secretly glad that there was trouble brewing between the roommates. My assumptions of needing a specific kind of “beauty” to feel attracted to someone, dissolved. I fantasized about holding hands and walking around campus and shopping for movie nights in the aisles of the campus store.

My fantasies—although innocently intimate and not-sexual—were definitely not platonic. My giddy butterflies were soon accompanied by the gut-wrenching sensation of starting to “question”.

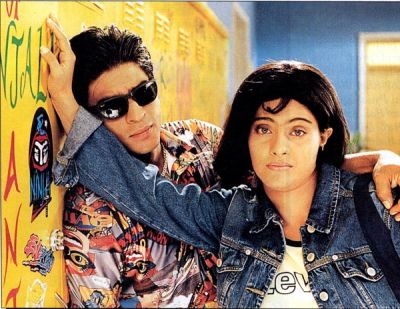

I had always liked boys—real and fictional. I had drooled over Season 2 Chandler. Gushed over Milo Ventimiglia in Gilmore Girls and This is Us. I had dreamed up scenarios where I was Annabeth Chase to Percy Jackson, Amy Santiago to Jake Peralta. I liked boys with silliness, heart and a sense of humour. My first relationship with a boy in my late teens had been healthy and safe, unlike everything I had heard about peoples’ firsts.

And so this infatuation for J was shocking. It felt like I had been straight all my life, and, out of nowhere turned gay.

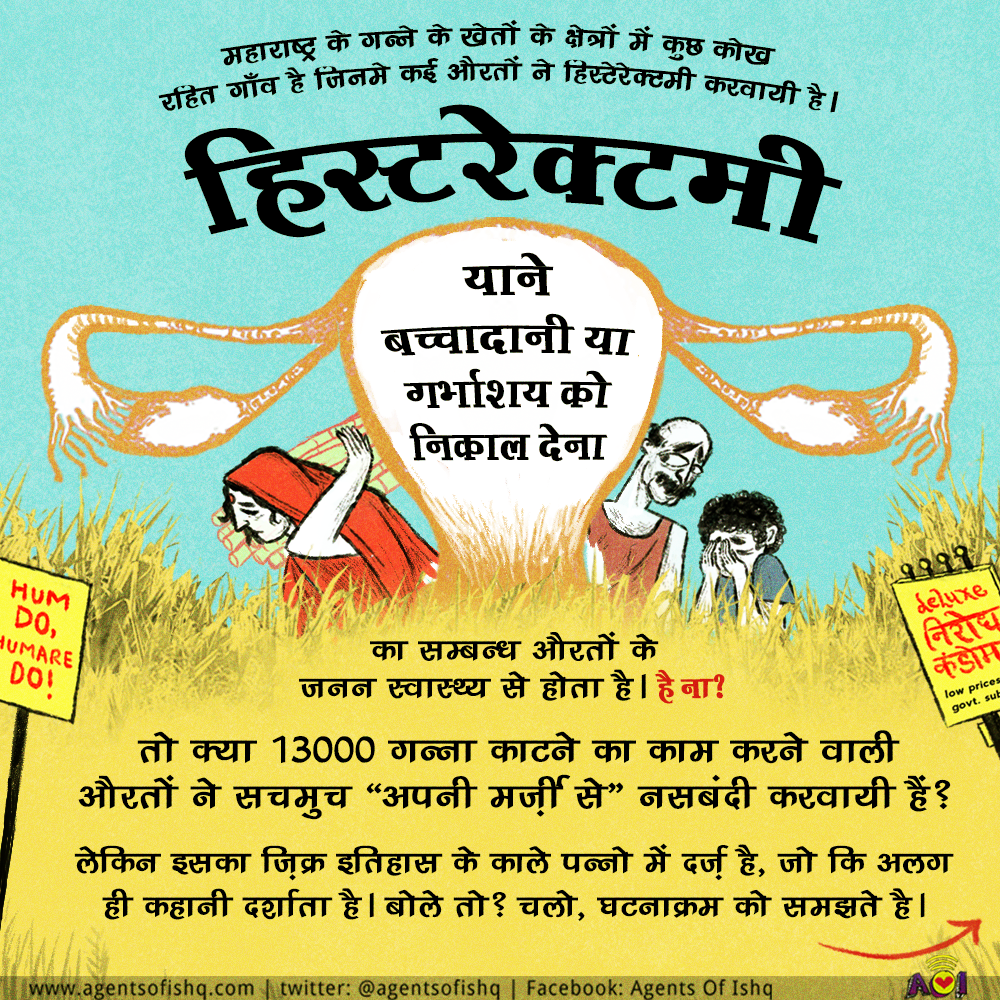

Listening to queer peoples’ stories made me feel like their journey began only once they “came out”. I tried to remember what I had been like before this. It was only in my first semester of college, when my classmate had proudly proclaimed herself as bisexual during an online class, that I’d started learning about what queerness was. I was taking complex courses—gender studies, film, history, classical and cultural sociology—all at the intersections of minority identities. I was meeting many new kinds of people, all at once. I felt the need and pressure to keep up, to expand my understanding of the world and to become “politically correct”. Being a “good ally” felt like an intrinsic part of my aspirations to becoming a writer, journalist and committing myself to the cause of social justice. Through the pandemic, I read endlessly about queer terminology and queer histories. To “perfect” the theory, even though (and perhaps, especially because) I didn’t know any real queer people.

Was I suddenly supposed to accept that I was now a “real queer person” myself? One was the more common fear that all queer kids experience—”Fuck, what am I going to tell my parents?” “Am I going to be this ‘other’ in society?” The other was tied to my internalized homophobia. How could I not be okay with being part of a community I had so actively tried to understand and be in solidarity of?

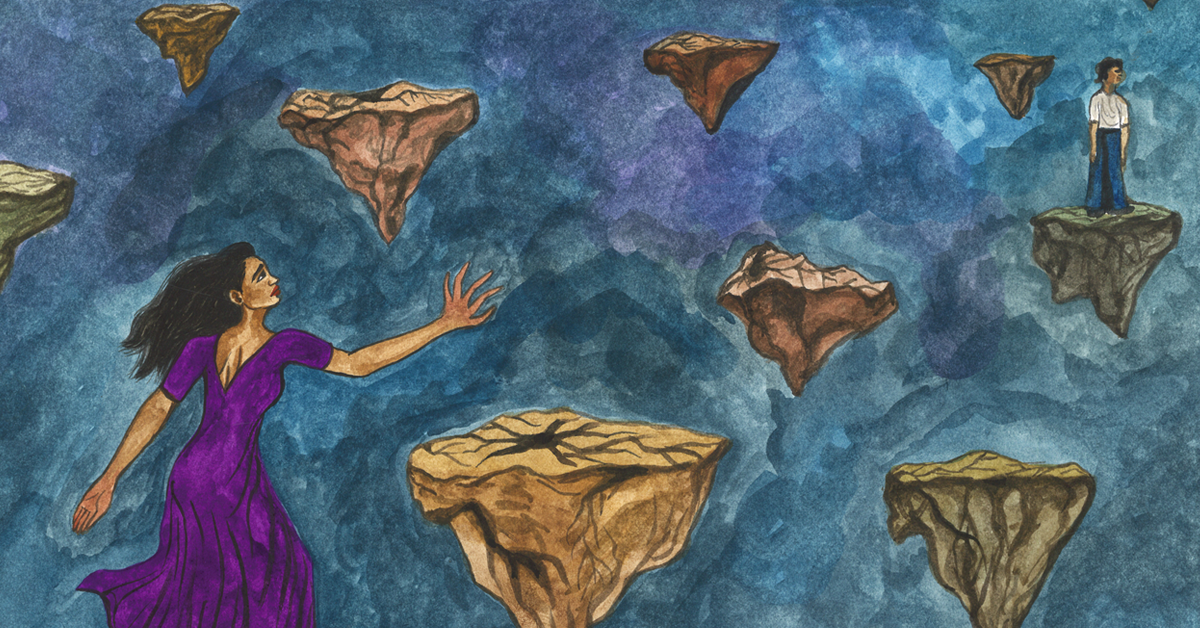

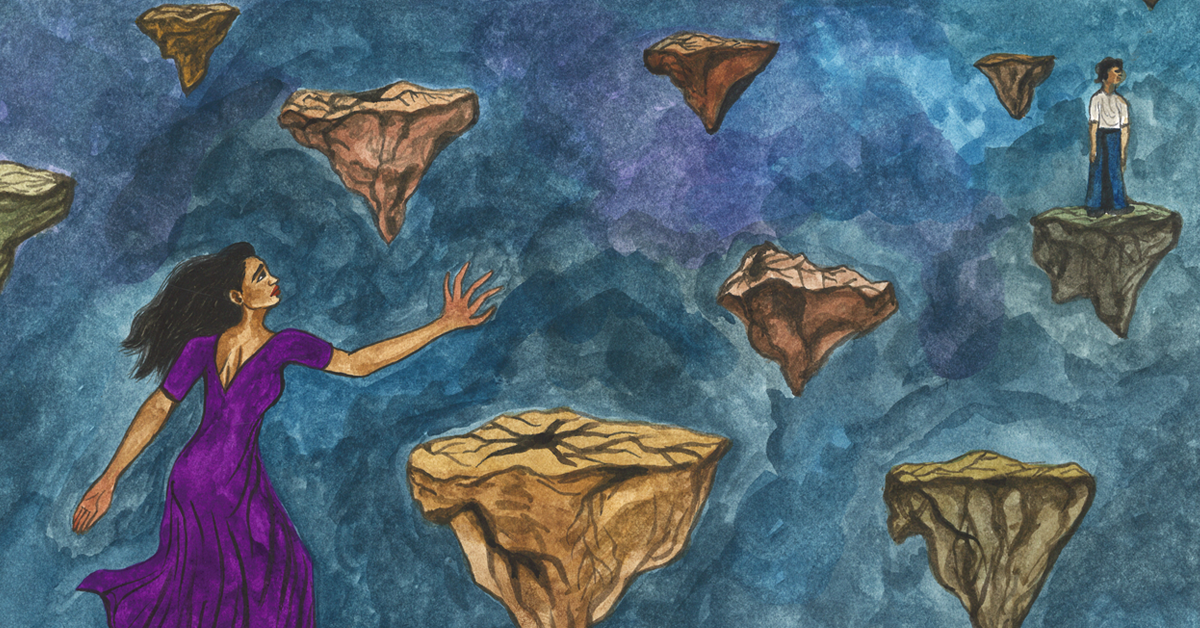

I held it in until I couldn’t anymore. I ‘officially’ came out to—surprise, surprise, J herself. I don’t remember much of that night on the hostel balcony, overlooking the ridges of hills, shrouded in the night. I just remember that I sobbed for three hours, asking the same garbled questions again and again. I remember there were lots of mosquitoes. I remember that J was the first person who ever saw me cry. That she held my wrist and didn’t let go.

I confessed my feelings for J a few days later , only to be gently let down. We promised to take space but honour and rebuild the friendship in the long run. She didn’t hear me sliding down and sobbing as the door closed behind her—I knew that things would never be the same again.

I returned to Pune for summer break in these throes of heartbreak. Soon after, I had a fallout with A (with whom my friendship had always been rocky). I was confident that J would either choose me or at least try to put in a sane word. Instead, she severed ties with me.

I felt like my queerness had been trampled over. I was too devastated to explore the possibilities of this universe that J had opened. I wanted to forget that I had been abandoned by the person in whom I confided a terrifying and intimate part of myself.

How was I going to survive? Friend groups had already been formed and it felt like life in Manipal had ended for me. I was bitter. My queer realization was the beginning of everything that had gone wrong. If I hadn’t fallen for J, we would still be the closest of friends. If I had taken more time, not been hasty, or not confessed, maybe things would have been okay. Why had I figured things out so quickly?

I met K in the next few weeks. Under shared umbrellas in Manipal’s torrential rain, identical plates of food in the mess, a perfectly complementary taste in music – something blossomed between us. I knew she liked me. I wasn’t sure whether I liked her back. And even if I did – I had finally managed to make one goddamn friend after the Semester 4 disaster. I didn’t want to put everything I had at stake again. My lovers became my best friends, my best friends became my lovers – Niyati, when would you learn your lesson?

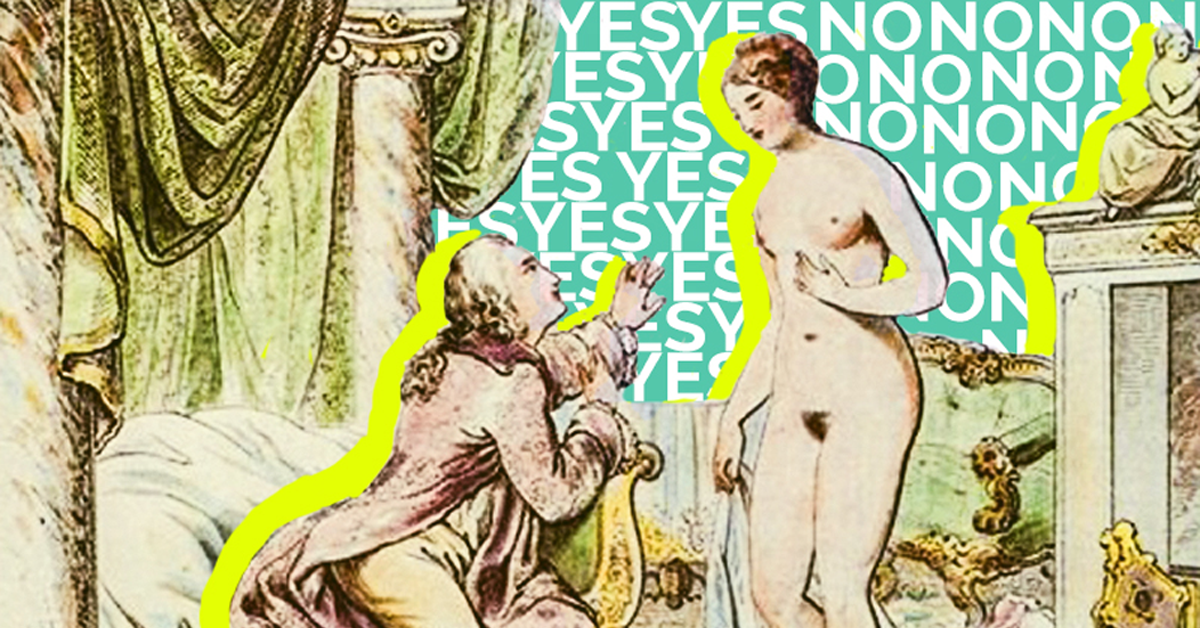

K and I started dating. It was strange – I had barely come out a few months ago, repressed my feelings for J during the summer break, and convinced myself that my queerness had just been a phase. I hadn’t been in any relationship for over a year and a half. But my journey with K made me feel like I had been queer all along. I had thought it would feel unnatural to kiss a woman. It didn’t. (It just scared the fuck out of me). We took long walks, nerded out over history, science and politics and knew how to comfort each other. She was goofy, I grounded her. I was anxious, she always made me laugh. It was easier to share anything and everything with a woman. A part of me instinctively sensed kinship and embraced her presence.

All year long, I had grappled with coming to terms with my identity privately. I didn’t feel the need to proclaim it in a grand announcement to the world or even to many of my friends back home. After all, I was still the same old me – and my being queer was just a natural extension of my world expanding.

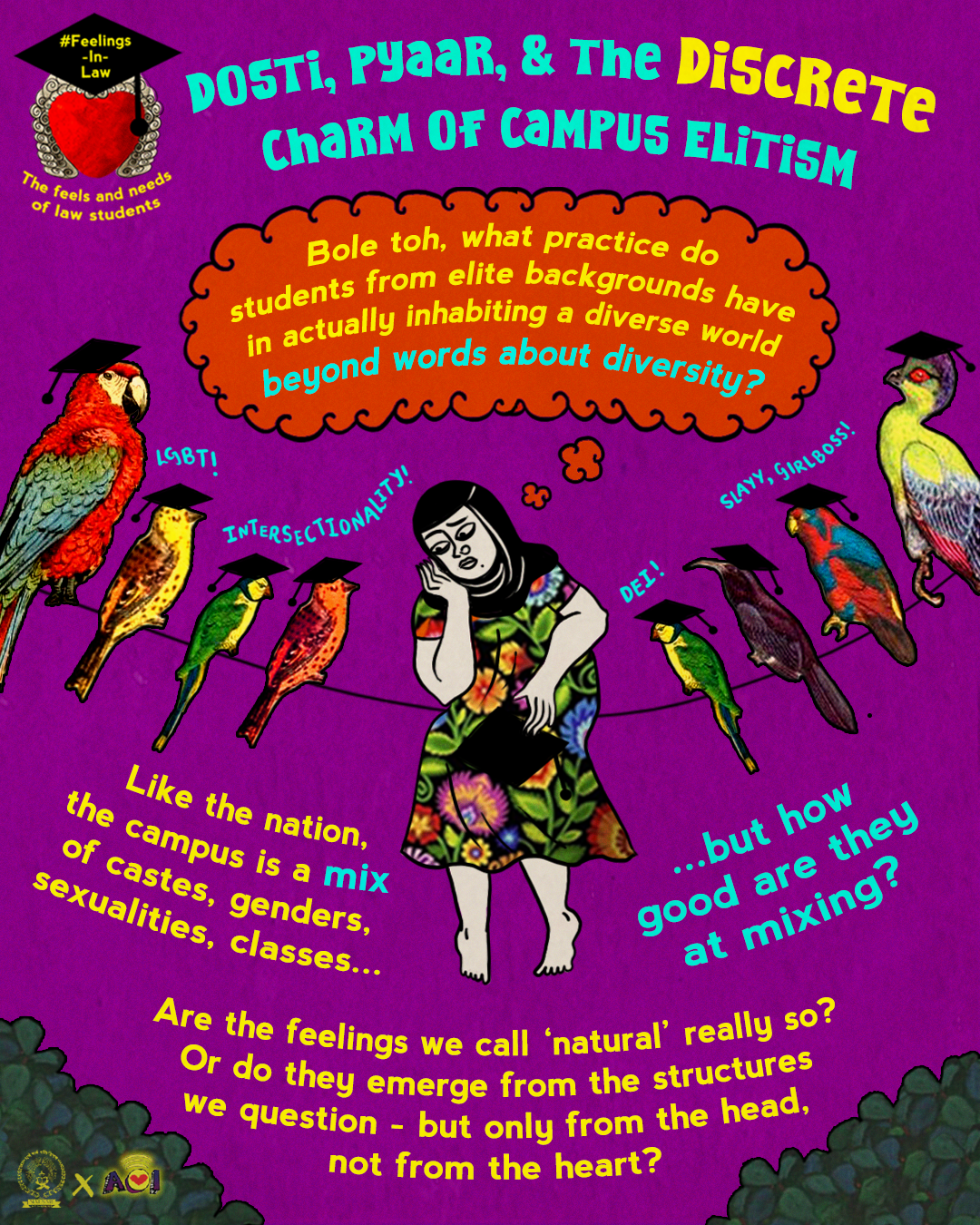

My department had many other queer people. But their tattooed bodies and coloured hair; their fierce opinions and seemingly perfect understanding of intersectionality intimidated me. Even though I was terribly lonely after the loss of my friends, it never occurred to me that I might reach out to them, and bond over our journeys. I was newly queer, what did I know anything about queer politics or even what being queer was? What if I overstepped or misspoke? Even before I became friends with them, I imagined a second ostracization – one that would shatter my queerness. In that sense, K was my one tenuous connection to the visible queer world. I was happy to be in a healthy relationship and it felt like I had fulfilled what I thought was the bare minimum required to be a queer person.

After graduating, I moved to Mumbai. Everybody was hustling, and seemed to know exactly what they wanted and how to get it. Again, I was scared to be a misfit here – a person who wanted to belong to a new city and call it home, but didn’t know how to.

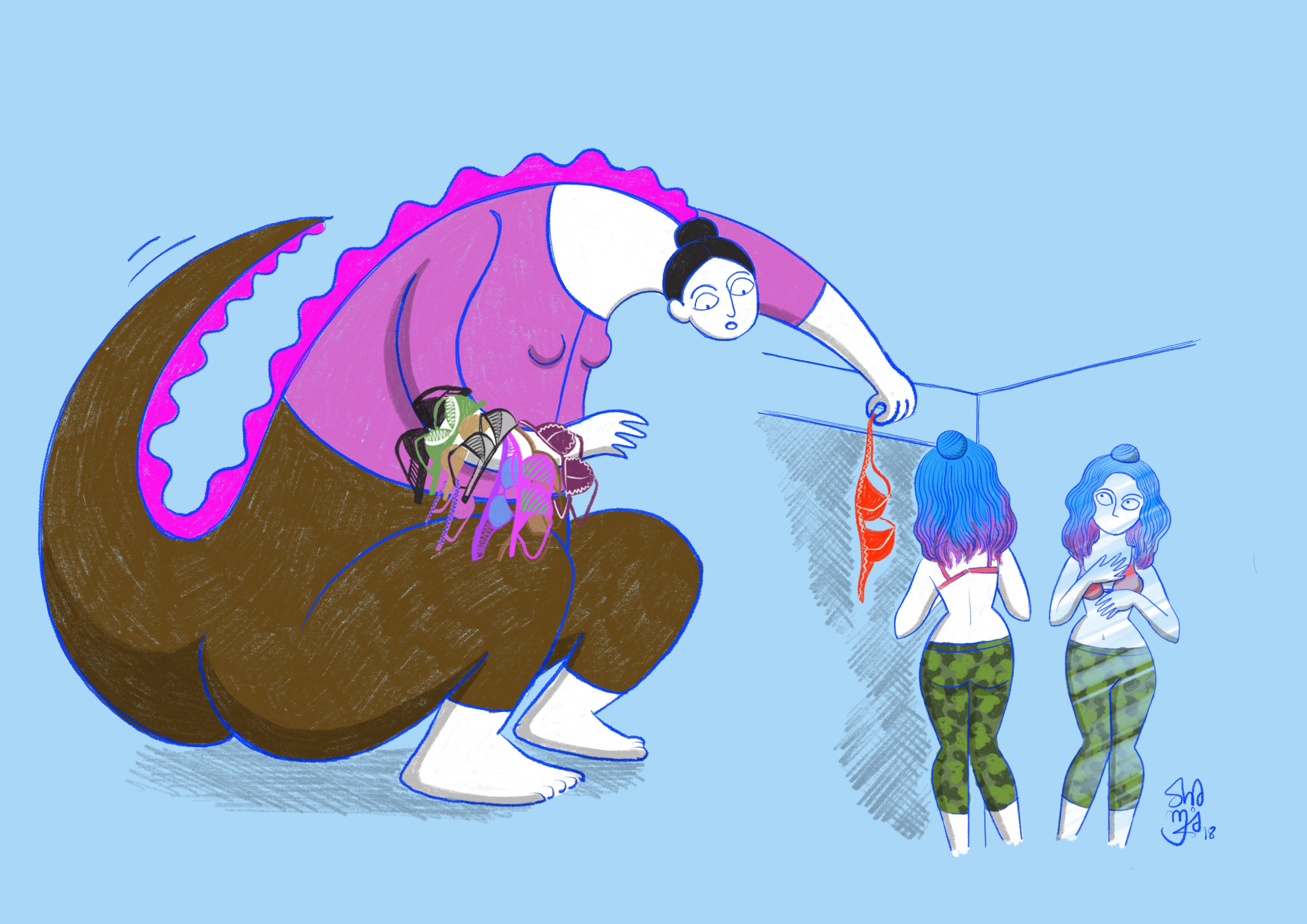

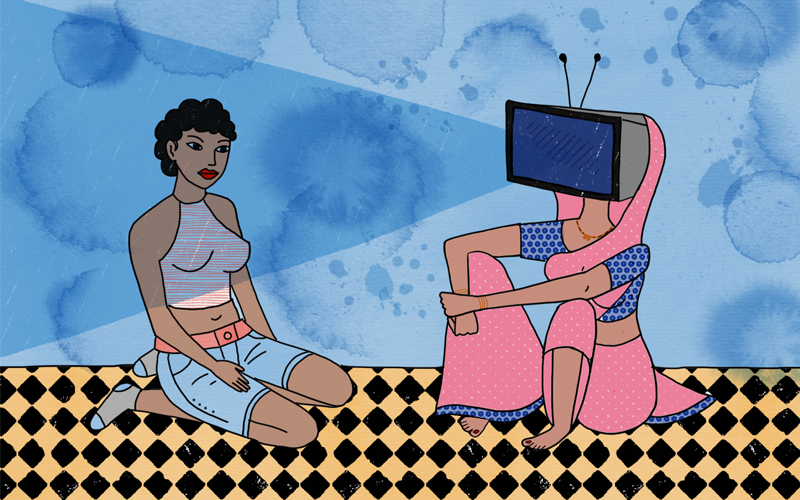

K and I had broken up by this time. With my one tenuous connection to the queer universe gone, was I even queer? Even though I had spent over a year getting intimate with my queer self, it once again felt like I was a novice to Mumbai’s gay scene. I felt more lonely than ever. I saw stories of parties organized by queer organizations, like Gaysi on Instagram. Everyone had brightly painted faces and dressed in sheer fabric and glitter. They seemed to drink, smoke and dance the night away. Queer people in this big city put their voice on display, while I was still a teetotaller bisexual woman who was easily mistaken for straight. Nobody would have been able to single me out in a crowd and say that I was queer. I, with my unchanged teenage wardrobe with solid colour t-shirts, jeans and unflattering pants and no sense of personal style. I, who seemed to not be aware of any queer pop culture references, I, who had never engaged with the politics of queerness because of the fear of being wrong. At that time, this felt ‘lesser’ than being loud and proud about my queerness.

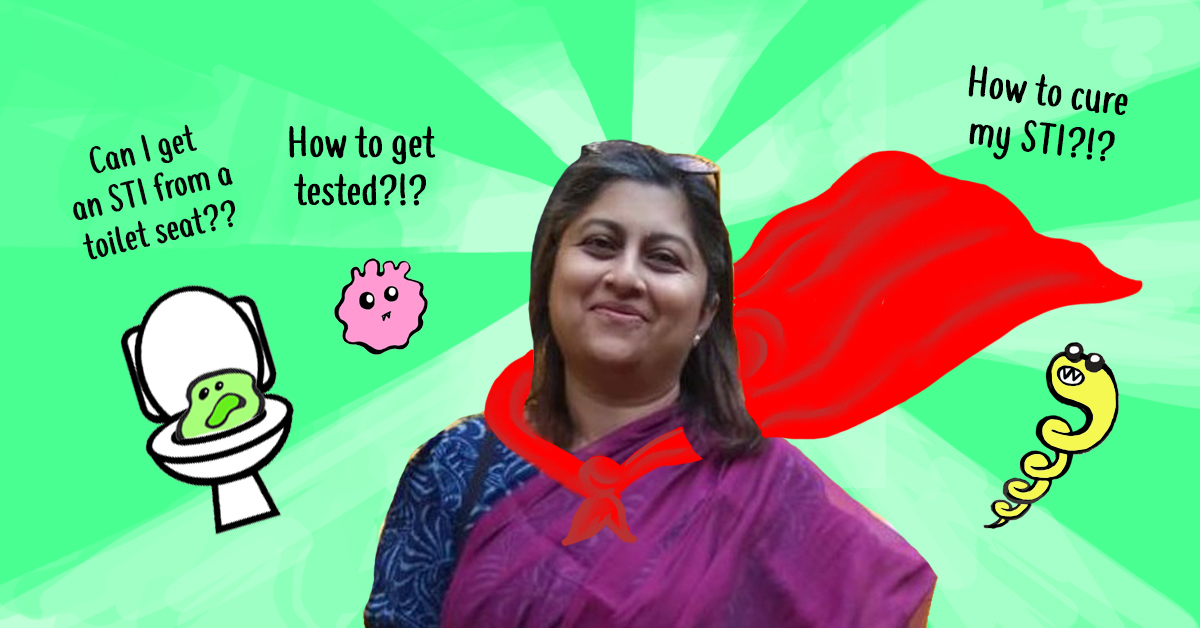

Then, I joined an organization with primarily queer employees. I had the same insecurities – was I going to awkwardly suspend between being straight and being gay? My first day at the office was when everybody had just returned from the annual Christmas break. I remember how person after person walked in through the doors, hugged each other tightly and exchanged gifts. They had piercings and shades of rainbow in their hair. They confidently wore bold coloured eyeliner with salwar kameezes and kurti-pants, confidently pulled off bright pieces of printed fabric and silk. They wore baggy pants and shorts and laughed about how ironic it was that a sex-ed space was filled with many people who identified on the asexual spectrum. They knew the ins and outs of popular queers in the city and every event that was happening in town. They sat on either side of me during lunch and played games with me. One person with shiny pink eye stickers noticed that I felt awkward and shyly slipped me a rabbit shaped scrunchie saying, “This is your Christmas gift”.

I was struck by the warmth and everyday-ness of this space. It didn’t feel like they were deliberately putting any part of their identity on display. We had incredible discussions on gender, sexuality, feminism and queerness every day. My queerness had just been my own until then. But in the steadiness of this space, which allowed me to be queer in whatever way I wanted to be. I could be straight-passing and just be as queer and feel as celebrated, I found that I wanted to finally engage with the wider community at large.

Labels felt peculiar. Straight, biromantic, heterosexual, bisexual, demisexual – I had swum my way through these to make some sense of who I was. I had believed that if I didn’t define myself fully, I was giving the world another chance to not acknowledge my existence. I had been surrounded by queer people before and had been scared of ‘getting it wrong’. Now in Mumbai, I was introduced to hundreds of these labels – with many people using lots of them all at once. These people had many different identities and self-expression. On the one hand, watching them inhabit this in-between space of fluidity felt freeing and expansive. On the other hand, I felt more intimidated and scared than ever before.

How was I supposed to dress, look and talk my way into this underground queer circuit? What should I put on my Hinge profile? What were these secret codes and words I wasn’t privy to? What was the use of coming out, I wondered, if I felt othered and intimidated by people supposed to be my own?

I initially struggled to understand the people behind the labels. These were words and phrases that queer people had invented to ‘break free’ from how society perceived them. Words that more correctly described a way of being in the world that a heteronormative world could not imagine. When I first came out, ‘queer’ had felt too scary, too big of a word. The word ‘bisexual,’ – being attracted to two or more genders (I ignored the ‘or more’ at the time – two was terrifying enough) – felt like an anchor.

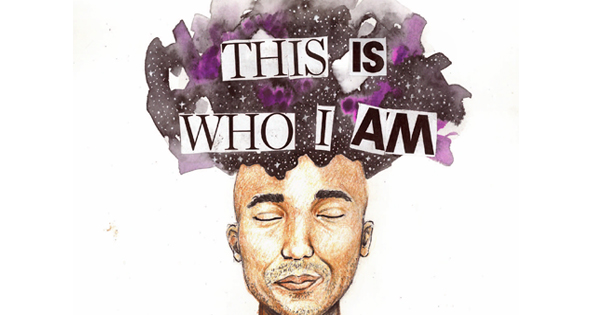

But surely labels couldn’t be the cumulative of who a queer person was? If we had invented labels to ‘break free’ and then used multiple labels for ourselves…would we escape one set of norms only to enter another box? Surely queerness was to be strange and unpredictable in the most delightful ways, because those ways were all yours. Surely, queerness did not look like any one thing. Did queerness even look like anything at all?

In the middle of all these questions, I was lucky to be initiated into the space of my queer colleagues – who soon became close friends. There was time to think, time to become, time to be unsure. My friends embodied the ‘cool’ queerness that I had hesitated to approach till now. They hop across events in the city with casual ease, put on makeup, dressed in the wildest, most beautiful ways that I felt I wasn’t brave enough to do, and talked passionately about social injustice.

I slowly started to experiment with myself in the wake of this steadiness that still allowed me to stumble sometimes. I wanted to experience how far my queerness could go. How boundless I could be as a person. Experience the spacious and incredible freedom that came with accepting that we stood out from the world.

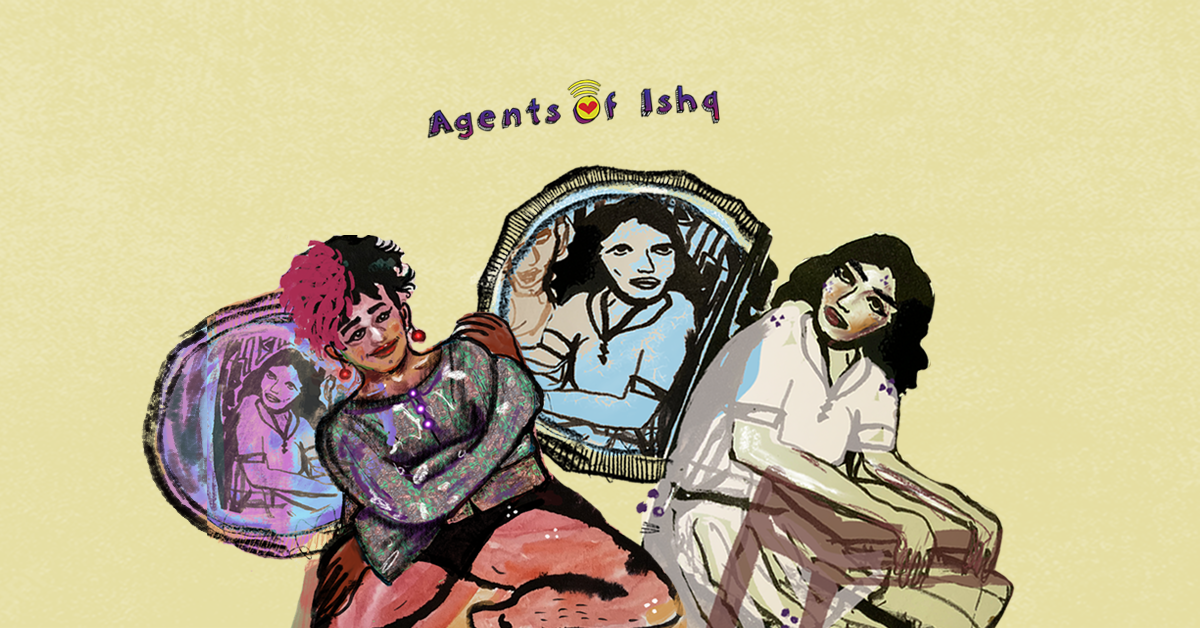

I chopped off my hair and got a tattoo. Had I done this earlier, I think I would have just done it to try and forcibly fit into the queer scene. Being uncertain and being allowed to feel like I was allowed to take my own journey, on my own terms, allowed me to experiment with my body and my assumptions. It felt more easy to imagine a world where I could be not just a straight-passing bisexual woman, but an uninhibited, queer person – but ONLY if I wanted to be. I could be one or the other, I could be somewhere in between, I could oscillate between the two, or find a completely different third thing. Nothing was lesser, nothing was inferior. I was just as queer in all my avatars.

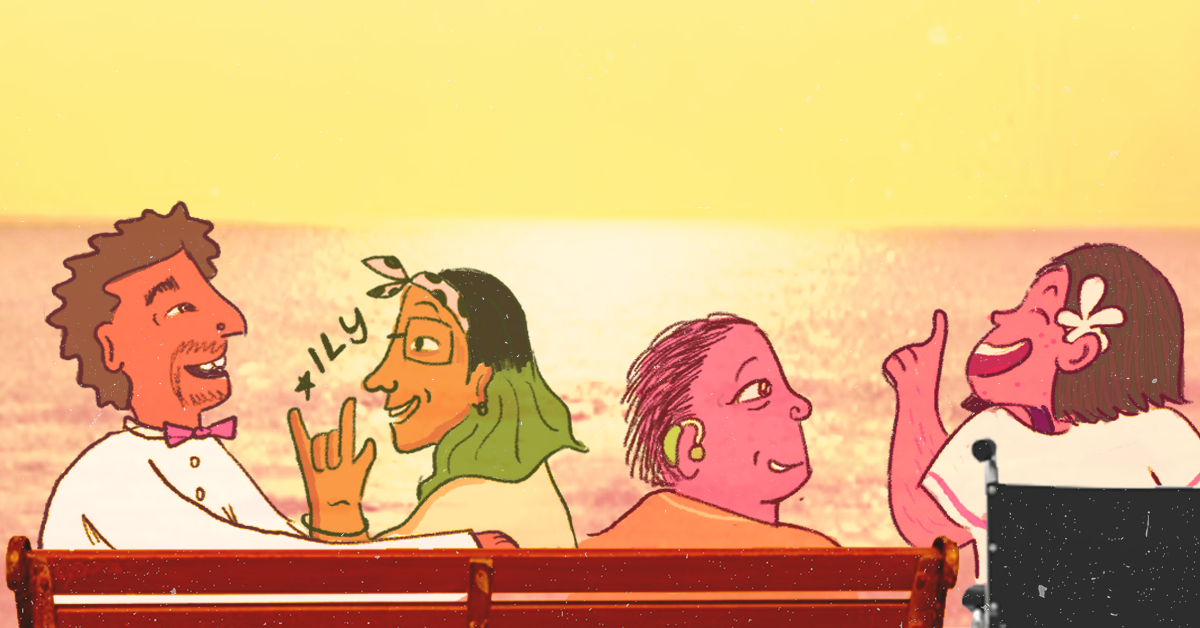

Being encircled in this warm jhund of friends also taught me so much about horizontal relationships. Until now, my partners were my best friends, the people I invested everything into. My queerness helped me imagine a world where there were no hierarchies between friendships and romance.

These days, I head over to their place on weekends. We cook pancakes. We read out poems to each other – heads on laps, limbs entangled. Sometimes, we dress up in campy outfits and go party. All of these can co-exist. We are a group of queer but ordinary friends – sharing our dreams, desires and grief.

On my ‘coming out anniversary’ every year, I wear the Pride shirt that K gave me. In a world that revels in being ‘loud and proud’, I speak my silences.

Today, I don’t feel the pressure to come out all at once to anybody. No such thing exists. I can come out in different ways and intensities to different people in my life. I feel more excited than scared to immerse myself into queerness now. To keep sliding down the rainbow. To keep coming out, again and again, and again.

Niyati is a reader and a writer. She is curious, loves to walk along beaches and believes that kindness can change the world.