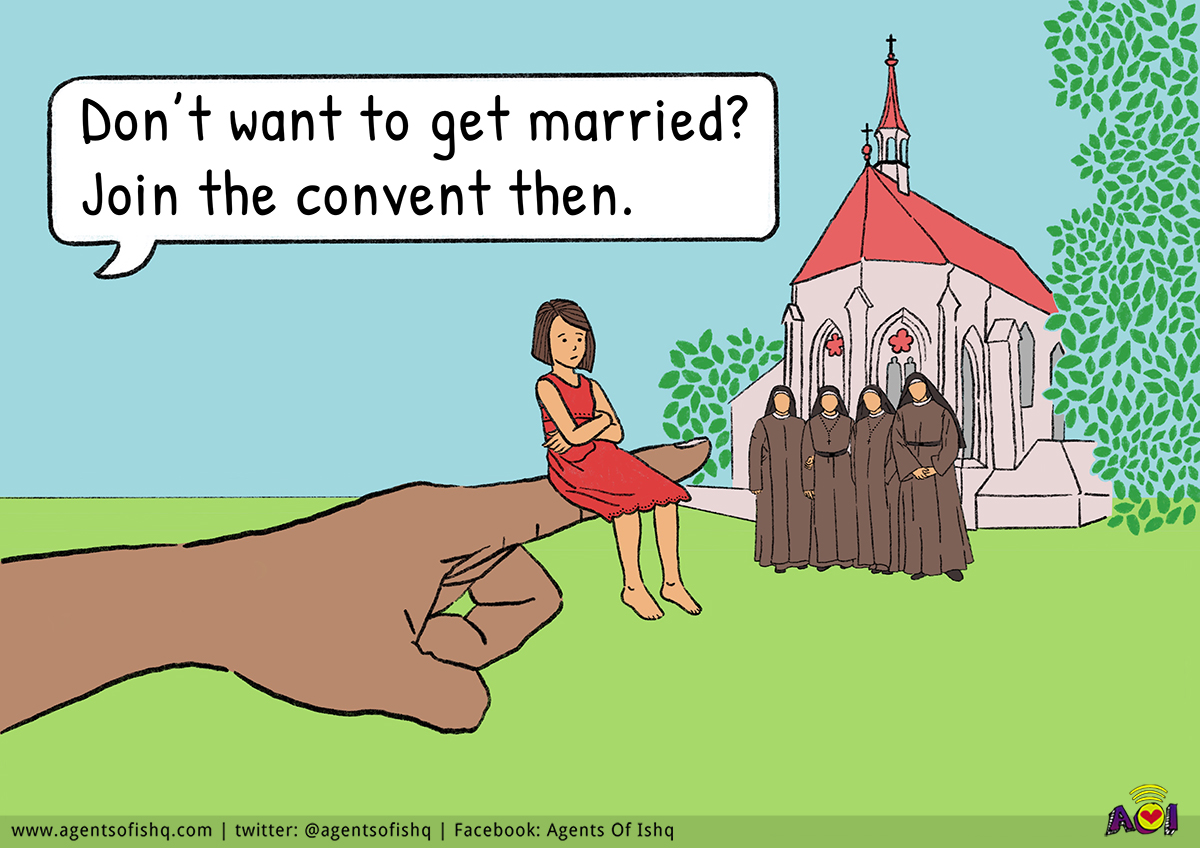

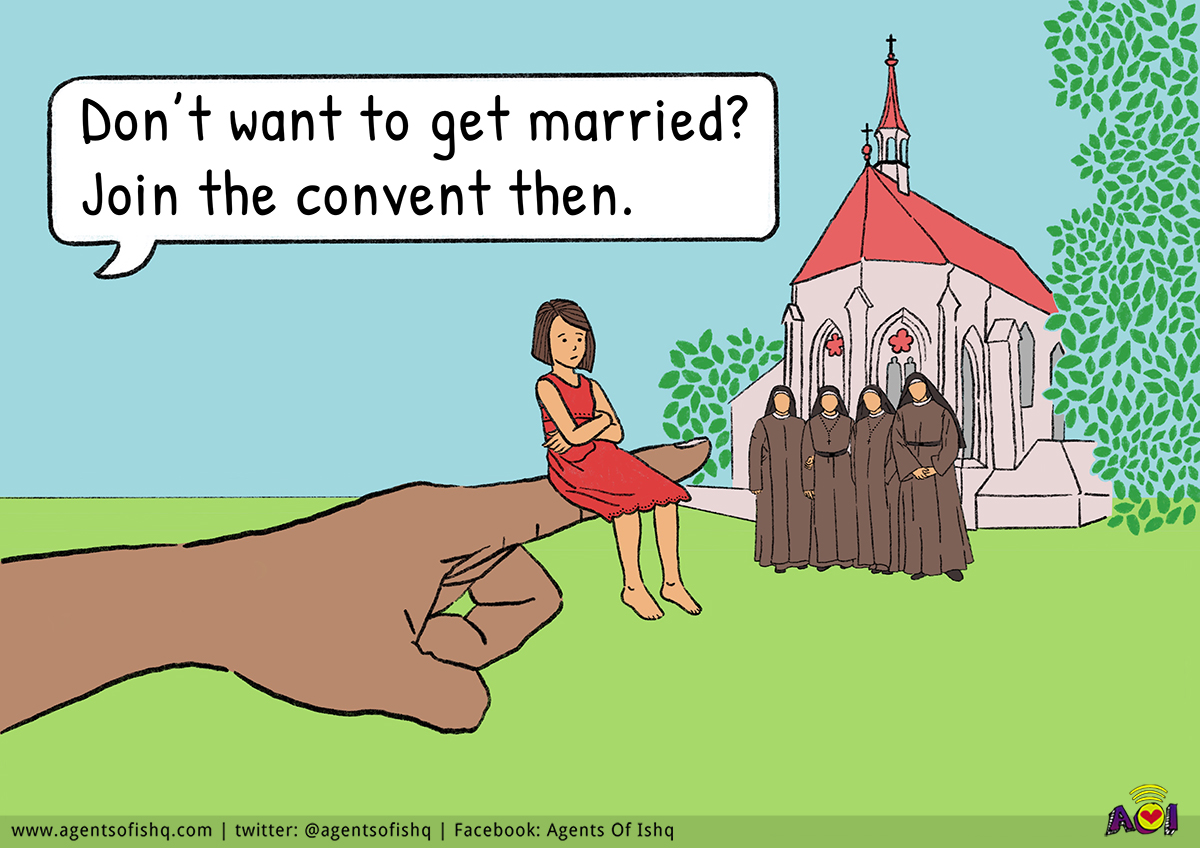

My grandfather believed he was a funny man. When I was a ten-year-old, he wanted to know when I would stop growing. According to him, my prospects of finding a groom taller than me were looking increasingly modest by the day. Being ten, I knew nothing about finding a groom, much less one appropriate in height. I said, Don’t worry, chacha, I’m not getting married. Chacha responded – Oho, are you going to join the convent then? It is a truth universally acknowledged that a single Malayali Christian woman in possession of a desire to remain unmarried must be in want of a convent. (My friend Sister Aquinas disagrees. This is her fifty-fifth year at the convent).  At fifteen, the age when the Naomi Campbells and Kate Mosses of the world were scouted by modelling agencies, I was greeted by a pair of nuns who (in some sudden and terrible lapse of judgement, I assumed) felt I’d be a good fit for the religious vocation. I was mildly upset at this proposition. Did I look so prosaic that the only thing I was getting scouted for was the nunnery? I wince now, at my insufferable teenager self.In the second year of college, a soon-to-be seminarian friend suggested I join the convent in order to give him company and proceeded to die laughing at what he believed was a very original joke. Little did he know that me joining the convent was the oldest running joke in my family. Last week, he called me. Among other things he told me about his new friend who was a nun. She had turned forty over the weekend and they had Chinese for lunch at the seminary that day. Her treat, he said.In the category of unmarried woman, nuns reigned supreme and so when a child announced she did not want to get married for reasons she herself did not know, humour was naturally found in imagining the ‘rebel’ child-turned-woman at a convent. If you weren’t going to marry a man, well you must marry God. Single woman? What’s that? When I relate these accounts to Sister Celine, she cackles and lets out with a sigh, Deivame nanni (God, thanks). It appears she is relieved I did not join the convent.

At fifteen, the age when the Naomi Campbells and Kate Mosses of the world were scouted by modelling agencies, I was greeted by a pair of nuns who (in some sudden and terrible lapse of judgement, I assumed) felt I’d be a good fit for the religious vocation. I was mildly upset at this proposition. Did I look so prosaic that the only thing I was getting scouted for was the nunnery? I wince now, at my insufferable teenager self.In the second year of college, a soon-to-be seminarian friend suggested I join the convent in order to give him company and proceeded to die laughing at what he believed was a very original joke. Little did he know that me joining the convent was the oldest running joke in my family. Last week, he called me. Among other things he told me about his new friend who was a nun. She had turned forty over the weekend and they had Chinese for lunch at the seminary that day. Her treat, he said.In the category of unmarried woman, nuns reigned supreme and so when a child announced she did not want to get married for reasons she herself did not know, humour was naturally found in imagining the ‘rebel’ child-turned-woman at a convent. If you weren’t going to marry a man, well you must marry God. Single woman? What’s that? When I relate these accounts to Sister Celine, she cackles and lets out with a sigh, Deivame nanni (God, thanks). It appears she is relieved I did not join the convent.  In 1964 Sister Celine or Celine Sister as I know her left for the convent with five of her classmates. Five from my class of fifteen. We are all nuns today. I ask her what made her want to become a nun. Well, she said, they held a camp on the last day of 10th class. And some of us signed up for it. We knew we were signing up to become nuns but we were also children. So even our best understanding about this commitment was limited. She adds – I too felt like marriage was not for me but that was just at the back of my head. It never occurred to me that I was becoming a nun to escape anything.I spoke to Celine Sister and other nuns with a very straightforward intention: poking my nose into their lives. The Malayalam films I grew up watching cast plain but pleasant women to play their nuns. The nuns on screen all had a certain pained look on their faces. Maybe because they were permanently required to be mild and maternal in a Mother Mary-esque manner. In the childhood relic Ayyappantamma Neyyappam Chuttu (2000), the plump Mother Superior dotes over an orphan child with a very adult name, Monappan. The nun in Priyam (2000) earnestly assists the romance of her best friend. But the nuns I know in real life have little interest in playing mumsy or cupid. My catechism teacher, Sister Beatrice, drove around in her little grey Alto doing errands that, to this day, I know nothing about. The one time she beckoned me warmly towards her I felt special and hoped she would mother me like the film nuns. But we parted ways shortly after she gave me a little talk about the inappropriate length of my shorts. I count this as my first heartbreak. Then there was Sister Grace, determined to spot any kala-pila between the boys and girls and diligently report it to our parents. At least she was honest in that she told us she would do exactly this. She was also prone to poking my ribs from behind with her bony fingers every time I nodded off during Sunday morning mass. I remember many of the nuns from my childhood as strict women with pursed lips because this is all I knew about them. Like the people who made the films I watched, I too had no idea who nuns were when they weren’t a mass in habits. I was always too terrified to ask them.Being asked to go join the convent always felt like a taunt because the picture painted in our jokes was that women in the convent led bland and uninspired lives. Therefore being sent to the convent would prove effective in curbing whatever unruliness denounced marriage in the first place.

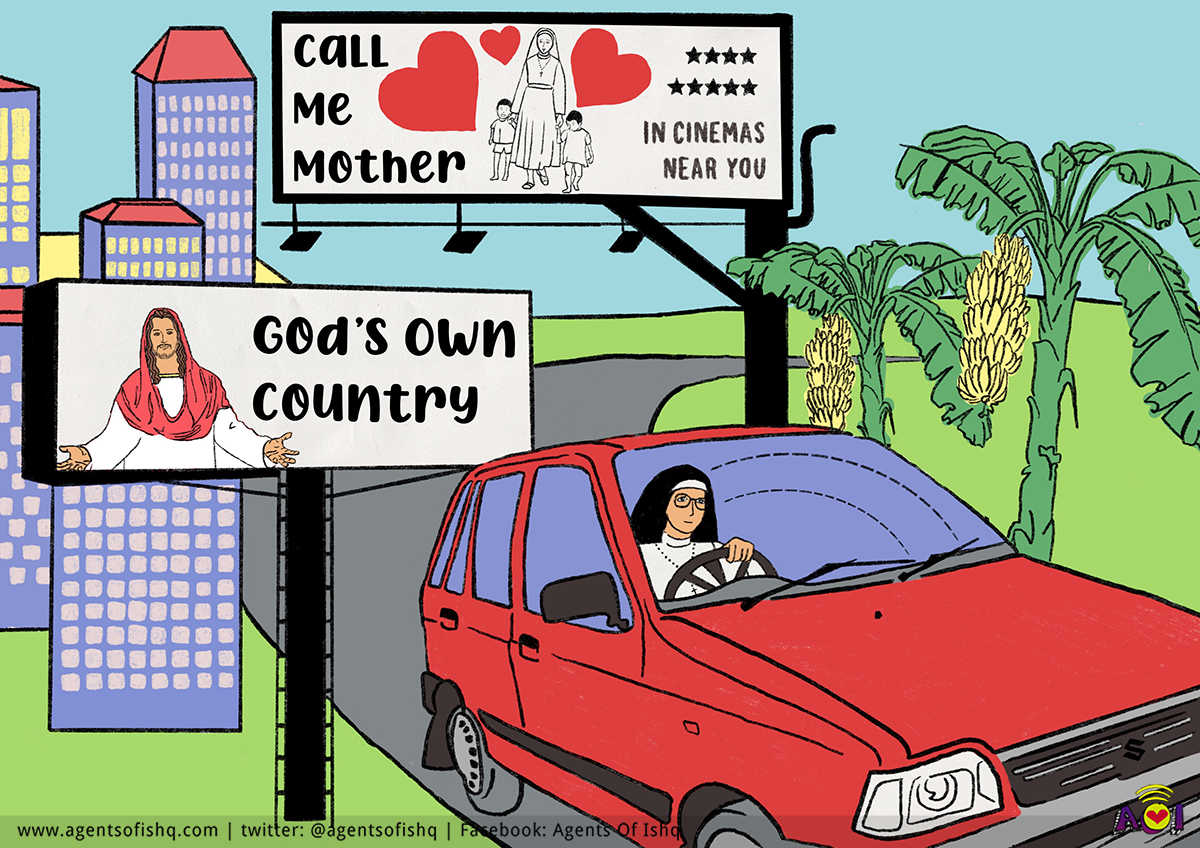

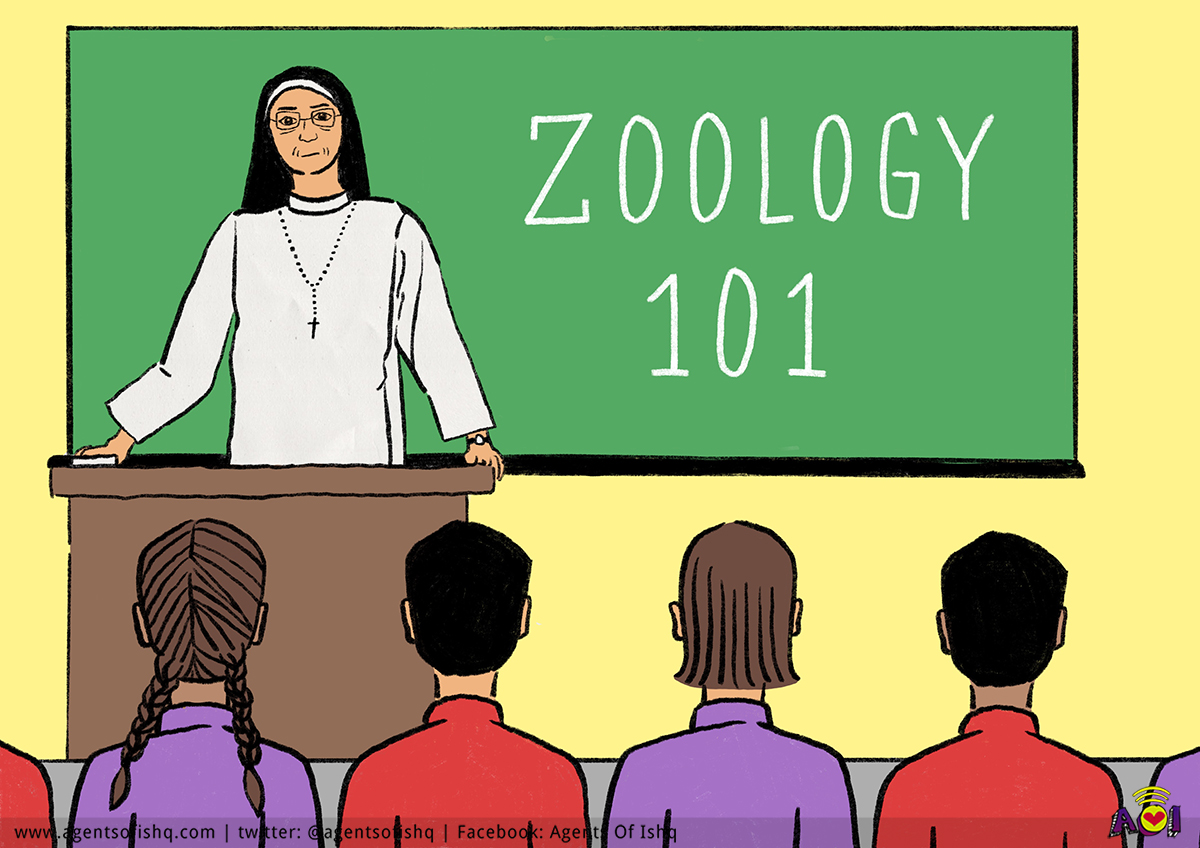

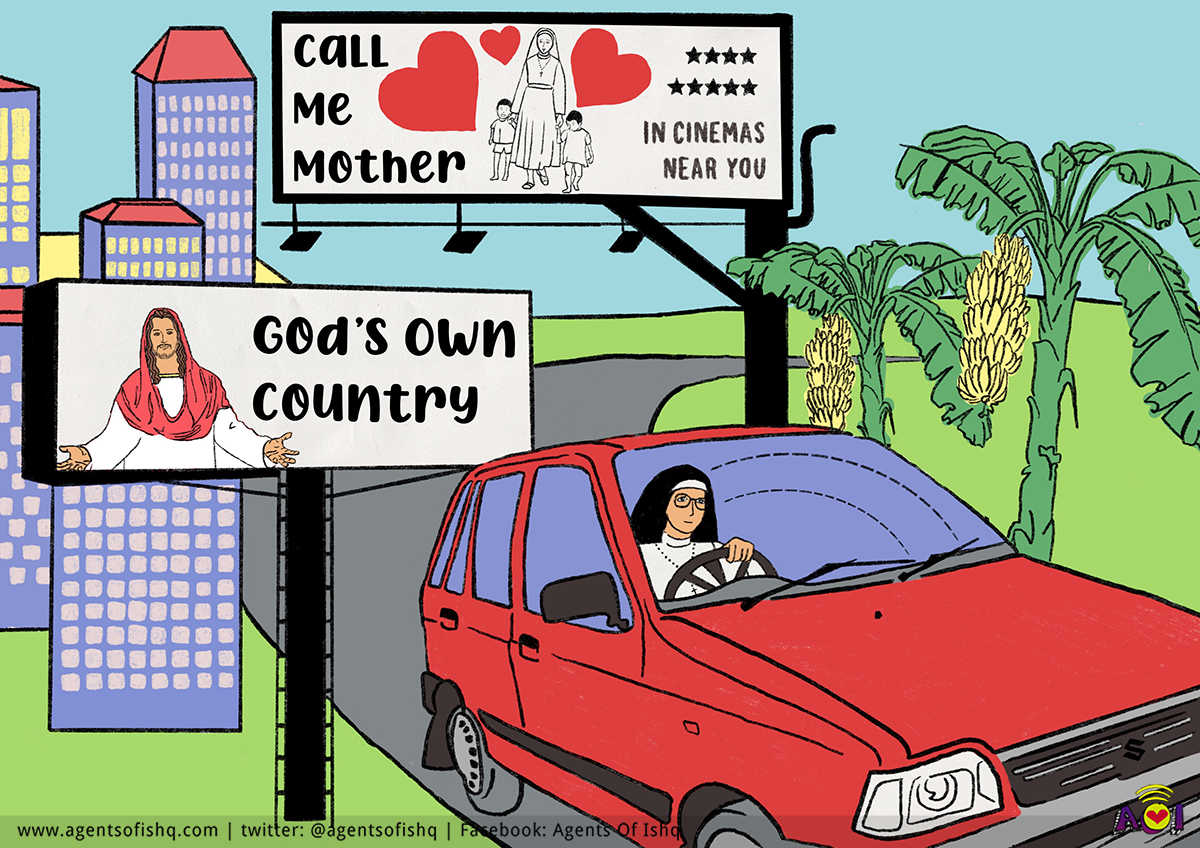

In 1964 Sister Celine or Celine Sister as I know her left for the convent with five of her classmates. Five from my class of fifteen. We are all nuns today. I ask her what made her want to become a nun. Well, she said, they held a camp on the last day of 10th class. And some of us signed up for it. We knew we were signing up to become nuns but we were also children. So even our best understanding about this commitment was limited. She adds – I too felt like marriage was not for me but that was just at the back of my head. It never occurred to me that I was becoming a nun to escape anything.I spoke to Celine Sister and other nuns with a very straightforward intention: poking my nose into their lives. The Malayalam films I grew up watching cast plain but pleasant women to play their nuns. The nuns on screen all had a certain pained look on their faces. Maybe because they were permanently required to be mild and maternal in a Mother Mary-esque manner. In the childhood relic Ayyappantamma Neyyappam Chuttu (2000), the plump Mother Superior dotes over an orphan child with a very adult name, Monappan. The nun in Priyam (2000) earnestly assists the romance of her best friend. But the nuns I know in real life have little interest in playing mumsy or cupid. My catechism teacher, Sister Beatrice, drove around in her little grey Alto doing errands that, to this day, I know nothing about. The one time she beckoned me warmly towards her I felt special and hoped she would mother me like the film nuns. But we parted ways shortly after she gave me a little talk about the inappropriate length of my shorts. I count this as my first heartbreak. Then there was Sister Grace, determined to spot any kala-pila between the boys and girls and diligently report it to our parents. At least she was honest in that she told us she would do exactly this. She was also prone to poking my ribs from behind with her bony fingers every time I nodded off during Sunday morning mass. I remember many of the nuns from my childhood as strict women with pursed lips because this is all I knew about them. Like the people who made the films I watched, I too had no idea who nuns were when they weren’t a mass in habits. I was always too terrified to ask them.Being asked to go join the convent always felt like a taunt because the picture painted in our jokes was that women in the convent led bland and uninspired lives. Therefore being sent to the convent would prove effective in curbing whatever unruliness denounced marriage in the first place. If I spoke to the women I wasn’t going to grow up to be, what would I learn?So, I set out to talk to some nuns, and maybe understand a very specific life I might have been expected to lead had I been a young woman in Kerala some decades ago. First, I spoke to Sister Aquinas. Then to Celine Sister. Later to Sister Vimala and others. Now I know two school teachers, a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, the co-owner of a chayakkada and a woman in love. Celine Sister herself is a retired Zoology professor. This year she turns seventy-four. But she tells me that she feels as young as sixty. Do I sound old to you? She asks me over call. I panic a bit but manage a near neutral No…? Exactly! I can feel her beam at me through the phone. That’s what they all tell me. Already I have fallen for this woman.

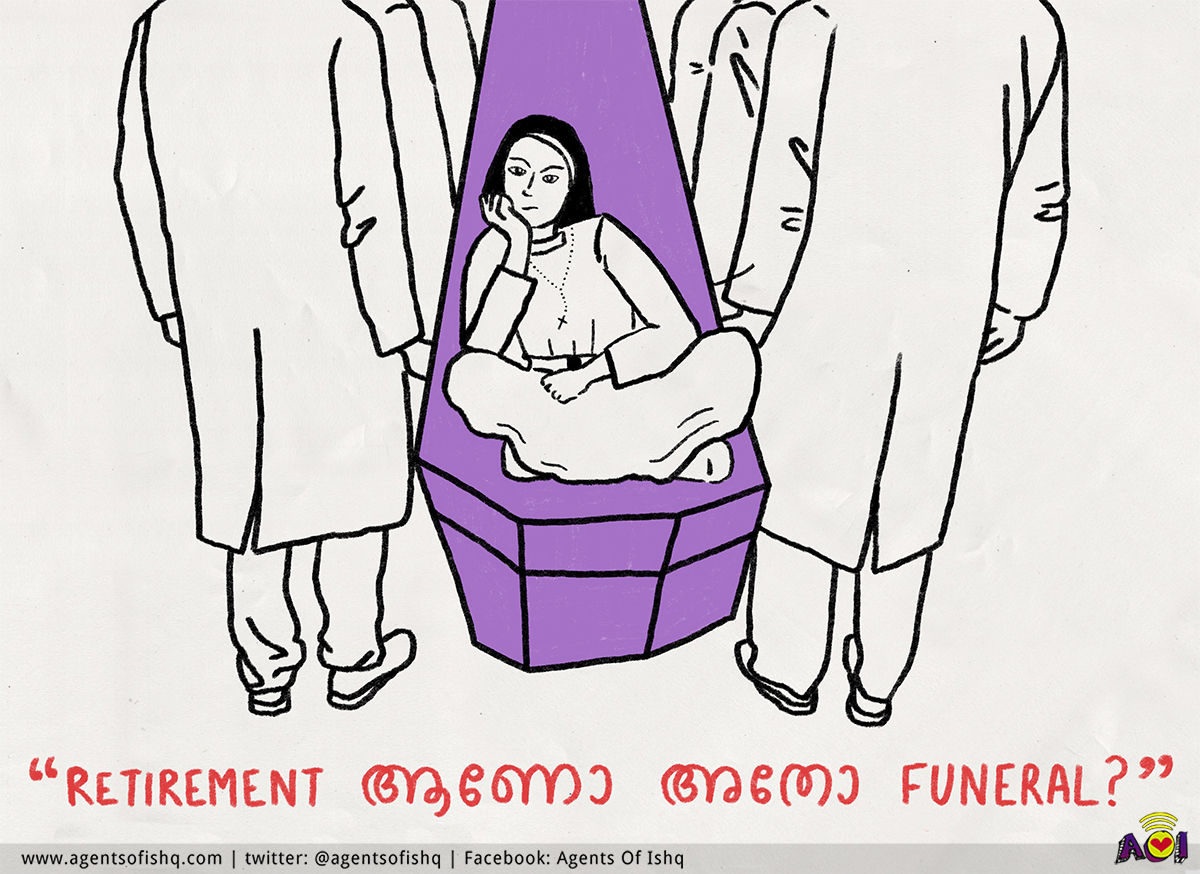

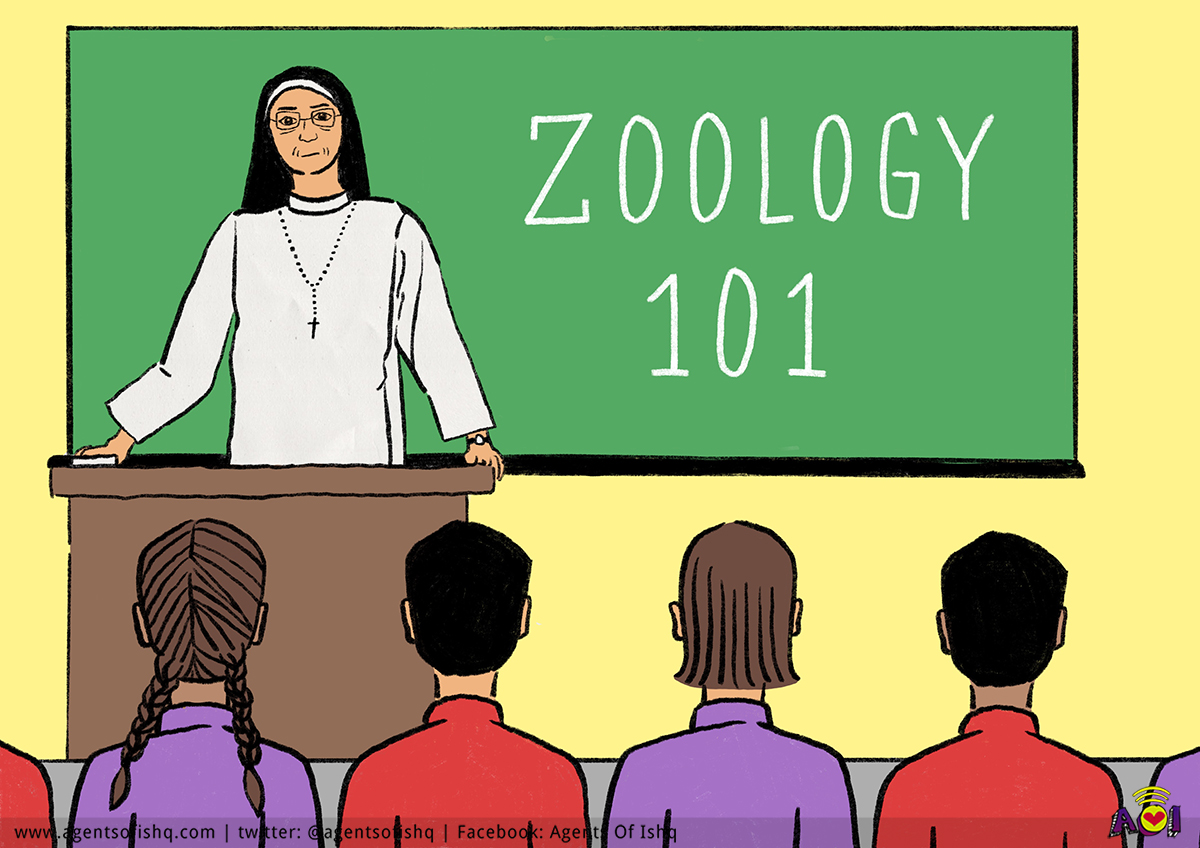

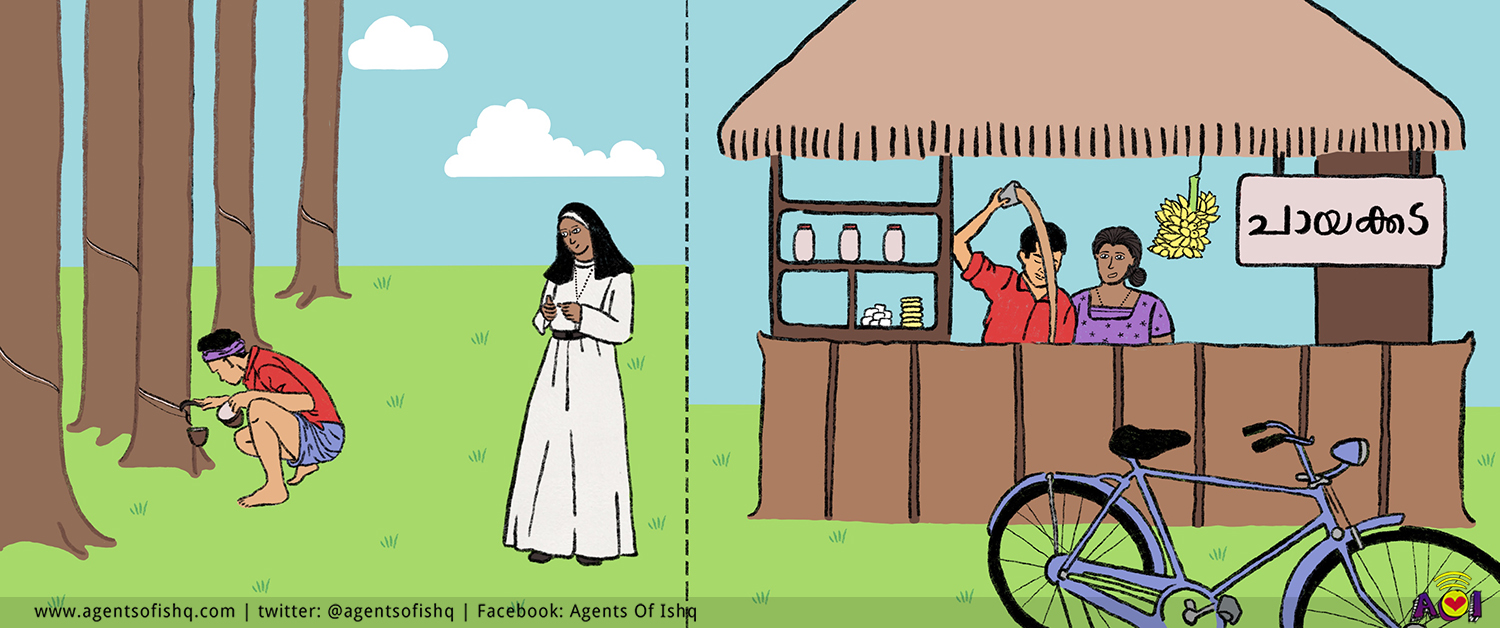

If I spoke to the women I wasn’t going to grow up to be, what would I learn?So, I set out to talk to some nuns, and maybe understand a very specific life I might have been expected to lead had I been a young woman in Kerala some decades ago. First, I spoke to Sister Aquinas. Then to Celine Sister. Later to Sister Vimala and others. Now I know two school teachers, a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, the co-owner of a chayakkada and a woman in love. Celine Sister herself is a retired Zoology professor. This year she turns seventy-four. But she tells me that she feels as young as sixty. Do I sound old to you? She asks me over call. I panic a bit but manage a near neutral No…? Exactly! I can feel her beam at me through the phone. That’s what they all tell me. Already I have fallen for this woman.  Occasionally Celine Sister interrupts our conversations to remark, But you must already know that about me, no? She is referring to her teaching years and the many adults I know who have studied under her. But the truth is, I know very little about Celine Sister as a teacher. I knew her for her frequent presence at funerals in the family. Weddings not so much. I knew her as chatty but not with me. I knew her only as a nun and of that identity too, I knew very little. Later, on another call, I ask the seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas at what point she started thinking of herself as an older woman. Well, not until now, she says with some amusement. I don’t consider myself old. But if you think I am, I suppose I must be old, alle? Feeling very sheepish, I make a quick and clumsy U-turn into the past. When Sister Aquinas talks about herself, she too shies away from any categorical understanding of her life. I ask her about the motivations behind her decision to become a nun. Did I not want to get married? Is that what you’re asking me? she asks me. I believe I became a nun because God called me to it. If I simply wanted to avoid marriage, I could not have remained long within the Church. Girls are confident now. There are many women who neither join the convent nor marry. They don’t have time for either. They might be happy. They might not be happy. I don’t know. I can tell you how it has been for me.In Kerala, and I’m sure elsewhere too, the word ‘Sister’ can be employed in an abundance of situations. In hospitals Sisters are nurses who look after you. At the church they are the nuns who look over you. More infrequently, the term ‘sister’ is actually used to address one’s sibling. Maybe because ‘sister’ is a word loaded with meanings of caregiving and kinship, I was given to assumptions about the maternal bearing of nuns. Or maybe because of how easy it is to think about women in terms of these divisions – married and single, caring and uncaring. As, the sisters – the nuns - spoke of themselves they slipped effortlessly out of the girdle of maternal instincts regularly expected of women, whether they reproduce or not.Celine Sister is a teacher first and everything else after that – I know this sounds unbelievable but when I step onto the podium of my classroom, I am possessed by some spirit. Outside the classroom I am a friend to my students. Inside it they are not my biggest fans but the feeling is mutual. When I bring up her nun-hood, she expertly guides me back into her classroom. It reminded me of an incident from college when a friend told a professor that she was like a mother to all of us. She winced and shot back with lots of feelings, Yuck.

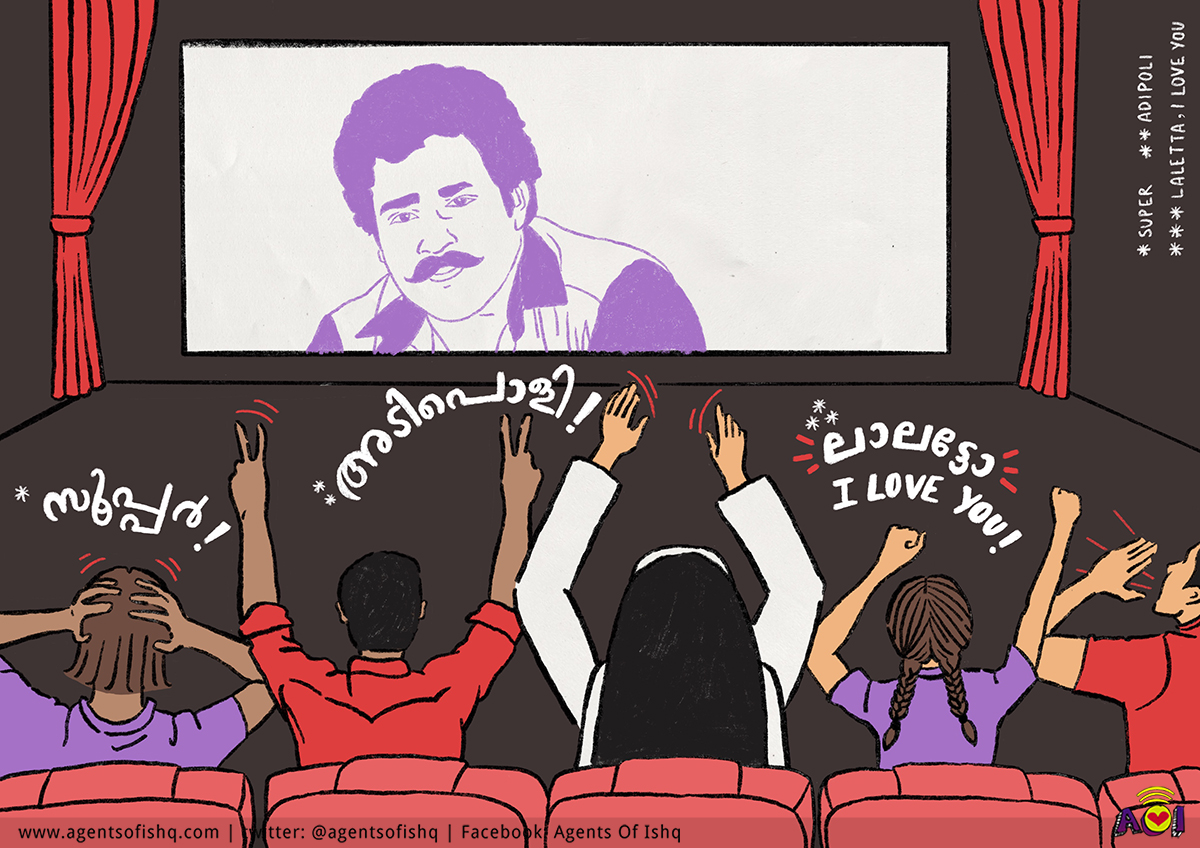

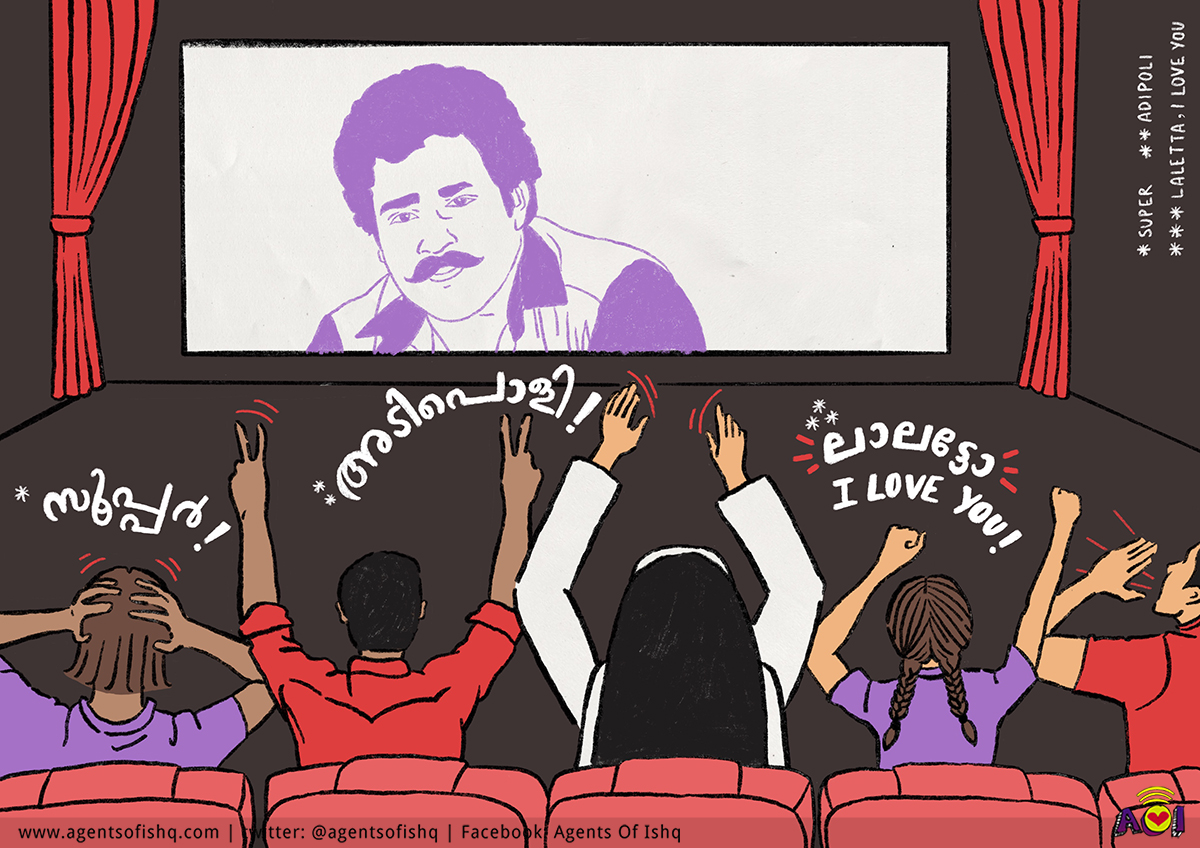

Occasionally Celine Sister interrupts our conversations to remark, But you must already know that about me, no? She is referring to her teaching years and the many adults I know who have studied under her. But the truth is, I know very little about Celine Sister as a teacher. I knew her for her frequent presence at funerals in the family. Weddings not so much. I knew her as chatty but not with me. I knew her only as a nun and of that identity too, I knew very little. Later, on another call, I ask the seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas at what point she started thinking of herself as an older woman. Well, not until now, she says with some amusement. I don’t consider myself old. But if you think I am, I suppose I must be old, alle? Feeling very sheepish, I make a quick and clumsy U-turn into the past. When Sister Aquinas talks about herself, she too shies away from any categorical understanding of her life. I ask her about the motivations behind her decision to become a nun. Did I not want to get married? Is that what you’re asking me? she asks me. I believe I became a nun because God called me to it. If I simply wanted to avoid marriage, I could not have remained long within the Church. Girls are confident now. There are many women who neither join the convent nor marry. They don’t have time for either. They might be happy. They might not be happy. I don’t know. I can tell you how it has been for me.In Kerala, and I’m sure elsewhere too, the word ‘Sister’ can be employed in an abundance of situations. In hospitals Sisters are nurses who look after you. At the church they are the nuns who look over you. More infrequently, the term ‘sister’ is actually used to address one’s sibling. Maybe because ‘sister’ is a word loaded with meanings of caregiving and kinship, I was given to assumptions about the maternal bearing of nuns. Or maybe because of how easy it is to think about women in terms of these divisions – married and single, caring and uncaring. As, the sisters – the nuns - spoke of themselves they slipped effortlessly out of the girdle of maternal instincts regularly expected of women, whether they reproduce or not.Celine Sister is a teacher first and everything else after that – I know this sounds unbelievable but when I step onto the podium of my classroom, I am possessed by some spirit. Outside the classroom I am a friend to my students. Inside it they are not my biggest fans but the feeling is mutual. When I bring up her nun-hood, she expertly guides me back into her classroom. It reminded me of an incident from college when a friend told a professor that she was like a mother to all of us. She winced and shot back with lots of feelings, Yuck. In our conversations, Sister Aquinas frequently returns to her friendships both inside and outside the congregation. My companions and I travel together. They have accompanied me across the country. And I feel like all the travelling I’ve done is nothing short of a blessing. It comes with my vocation. She adds, You know, I have grown to like being an older nun. It means more respect, more esteem and I’m not mad at all. She speaks fondly of her friends back home, many of them who continued to visit her even after she left for the convent. Nothing much has changed. They have their families. And I too have my work. But we have our childhoods in common. No two nuns were alike. But nearly all the nuns flitted uncomfortably at the mention of that sinister creature, the single woman. Did you not feel confident as a young woman? I ask Sister Aquinas in response to her feelings about girls now. Her response is quick – It did require confidence to leave home and join the convent. Even today. But being a single woman comes with consequences. From your own family and from society. Frankly, it’s an uphill battle. Besides, it was not ‘single’ I was trying to be.None of the stories lingered even accidentally over their single women aka unmarried statuses. Their stance is a very Yes, we are unmarried. And what about it? And I too begin wondering – Yeah, no? What about it?And yet, in another universe, Celine Sister might not have joined the convent, she says. All my friends were going. I just went along. It was just like school. Except we studied to become nuns along with other subjects. Homesickness in the first month. Crying to sleep through the nights. The occasional parent or sibling who visited her. She tells me she was never particularly pious. I was never the girl who went for mass regularly. Nobody knew me for my godliness. But in the end, I was the one who ended up a nun! She tells me she loves being a nun because it is an extension of her teaching. Some people cannot see that I really do enjoy my job, even at my age, Sister Celine says. I am now in my seventies but I keep myself busy. I sew, I mend and I garden. I still teach and still have duties to discharge. And you know what? I wouldn’t change a thing. For Sister Aquinas too, being a nun exists alongside her line of work as a social worker.. In fact, the religious vocation often enables and is a conduit for her profession. Born into an aristocrat family, Sister Aquinas laughs when she tells me she did not want to make the rich any richer. She quickly adds, now don’t go write about me like I’m some communist nun. It’s a cliche, she says, but I became a nun because I really did have a calling. Celine Sister is a Mohanlal fan. When I was a hostel warden I used to take my kids to the movies nearly every weekend, she says. And we never missed anything with Mohanlal in it. Later I ask seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas to pick between Mammooty and Mohanlal. Neither. Sathyan is my hero. What about Prem Nazir? I ask her. She briefly considers the option. No, not him. He was always just walking around singing. The Malayalam word for nun is kanyasthree (കന്യാസ്ത്രീ). It is one of those words which when translated into English tend to sound somewhat abysmal — virgin woman. I’m petrified to bring up celibacy in conversation. But I attempt to make a clean segue from Mohanlal and Sathyan to their sexual desires and fantasies growing up.

In our conversations, Sister Aquinas frequently returns to her friendships both inside and outside the congregation. My companions and I travel together. They have accompanied me across the country. And I feel like all the travelling I’ve done is nothing short of a blessing. It comes with my vocation. She adds, You know, I have grown to like being an older nun. It means more respect, more esteem and I’m not mad at all. She speaks fondly of her friends back home, many of them who continued to visit her even after she left for the convent. Nothing much has changed. They have their families. And I too have my work. But we have our childhoods in common. No two nuns were alike. But nearly all the nuns flitted uncomfortably at the mention of that sinister creature, the single woman. Did you not feel confident as a young woman? I ask Sister Aquinas in response to her feelings about girls now. Her response is quick – It did require confidence to leave home and join the convent. Even today. But being a single woman comes with consequences. From your own family and from society. Frankly, it’s an uphill battle. Besides, it was not ‘single’ I was trying to be.None of the stories lingered even accidentally over their single women aka unmarried statuses. Their stance is a very Yes, we are unmarried. And what about it? And I too begin wondering – Yeah, no? What about it?And yet, in another universe, Celine Sister might not have joined the convent, she says. All my friends were going. I just went along. It was just like school. Except we studied to become nuns along with other subjects. Homesickness in the first month. Crying to sleep through the nights. The occasional parent or sibling who visited her. She tells me she was never particularly pious. I was never the girl who went for mass regularly. Nobody knew me for my godliness. But in the end, I was the one who ended up a nun! She tells me she loves being a nun because it is an extension of her teaching. Some people cannot see that I really do enjoy my job, even at my age, Sister Celine says. I am now in my seventies but I keep myself busy. I sew, I mend and I garden. I still teach and still have duties to discharge. And you know what? I wouldn’t change a thing. For Sister Aquinas too, being a nun exists alongside her line of work as a social worker.. In fact, the religious vocation often enables and is a conduit for her profession. Born into an aristocrat family, Sister Aquinas laughs when she tells me she did not want to make the rich any richer. She quickly adds, now don’t go write about me like I’m some communist nun. It’s a cliche, she says, but I became a nun because I really did have a calling. Celine Sister is a Mohanlal fan. When I was a hostel warden I used to take my kids to the movies nearly every weekend, she says. And we never missed anything with Mohanlal in it. Later I ask seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas to pick between Mammooty and Mohanlal. Neither. Sathyan is my hero. What about Prem Nazir? I ask her. She briefly considers the option. No, not him. He was always just walking around singing. The Malayalam word for nun is kanyasthree (കന്യാസ്ത്രീ). It is one of those words which when translated into English tend to sound somewhat abysmal — virgin woman. I’m petrified to bring up celibacy in conversation. But I attempt to make a clean segue from Mohanlal and Sathyan to their sexual desires and fantasies growing up. Sister Aquinas says she won’t lie. I went for confession. And if that didn’t work, I would cry. Sometimes when I was overcome with feelings, I went into the chapel and had a good cry. It always made me feel better. Sister Celine tells me, It’s normal that we too have human feelings. But the point is that I overcome all obstacles. She says that Mother Mary is her go to lady. Sister Aquinas recalls an early interaction with her mother before joining the convent. My mother took me to a statue of Mother Mary outside our church and told me I couldn’t cling onto her anymore. Mother Mary would be my substitute mother. And that’s how it’s been since then.Sister Aquinas insists that she would not have remained in the convent if it weren’t for the older nuns who understood her as a young girl. We are all companions in the convent, old and young, says Sister Celine. You know, we are all busy women. More than you’d imagine. Pockets of friendship formed in their brief interactions with the mutual understanding that companionship was nearly always temporary owing to their vocation.

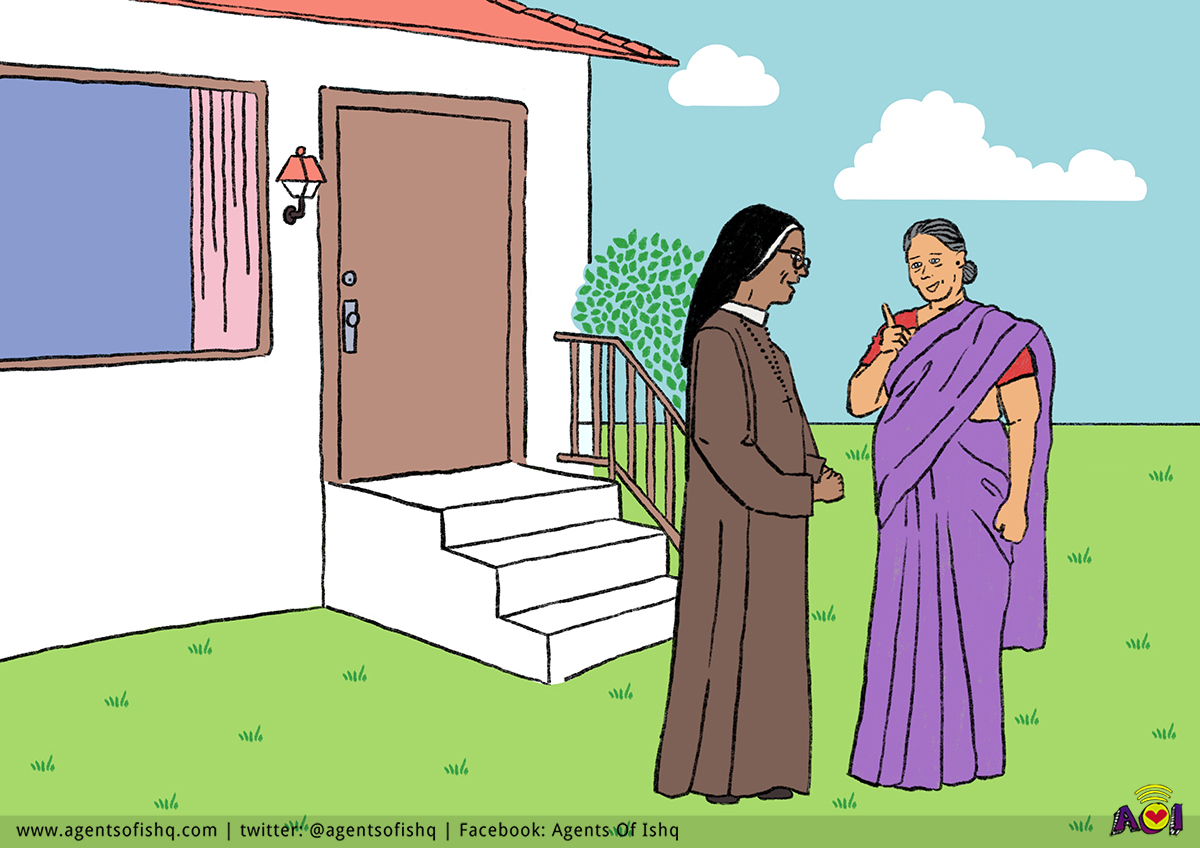

Sister Aquinas says she won’t lie. I went for confession. And if that didn’t work, I would cry. Sometimes when I was overcome with feelings, I went into the chapel and had a good cry. It always made me feel better. Sister Celine tells me, It’s normal that we too have human feelings. But the point is that I overcome all obstacles. She says that Mother Mary is her go to lady. Sister Aquinas recalls an early interaction with her mother before joining the convent. My mother took me to a statue of Mother Mary outside our church and told me I couldn’t cling onto her anymore. Mother Mary would be my substitute mother. And that’s how it’s been since then.Sister Aquinas insists that she would not have remained in the convent if it weren’t for the older nuns who understood her as a young girl. We are all companions in the convent, old and young, says Sister Celine. You know, we are all busy women. More than you’d imagine. Pockets of friendship formed in their brief interactions with the mutual understanding that companionship was nearly always temporary owing to their vocation. Sister Vimala, though, made very few friends in the convent. She left the convent aged fifty-two because of the abusive treatment meted out to her there. It was hard for me to live within a system of rigid rules, cruelty and jealousy. With a lawyer backing her and substantial pension to live on she was ready for battle. The first time she expressed her desire to leave the convent her companions tried coaxing her out of it. The second time, she was taken to a psychiatrist who deemed her mentally unfit. Initially, my mother stood by me even when others frowned upon my decision. But when the situation worsened, even my ties with amma came loose. Backlash was inevitable and nobody had to warn her. I debated everything and endured all hardships for years before I arrived at my decision. Even then this was a challenging migration and continues to remain so. But nobody can tell me I made a mistake. I was a lecturer alongside and had earnings from that. I know women who want to leave but cannot since they have no jobs or families to support them outside. Though no longer a nun, she still likes to go by the name Sister Vimala. People kept forgetting I had left the convent even when I walked among them in churidar and sarees, out of the nun’s habit. Even my lawyer, the day we finalised the legalities of the process and she was leaving, waved at me from her car and said, “Goodbye and good luck, Sister Vimala!” So I tell everyone I meet to call me Sister Vimala. I like it that way.

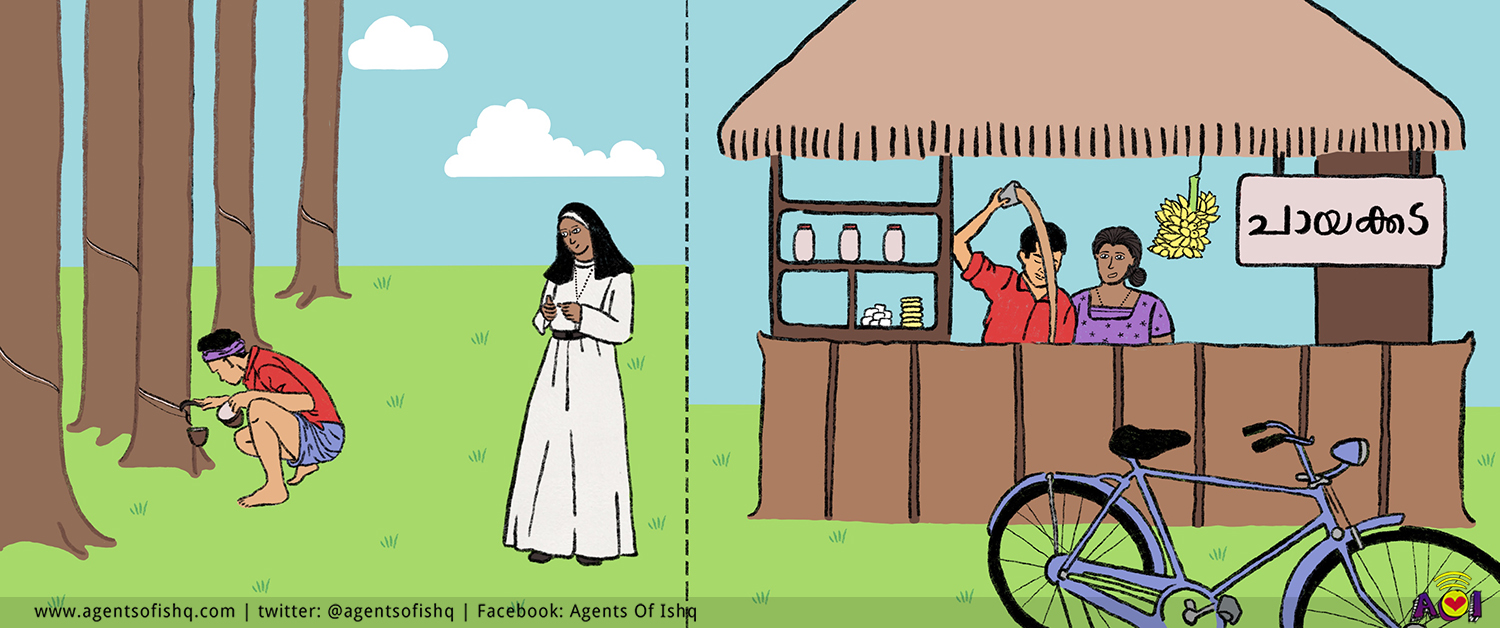

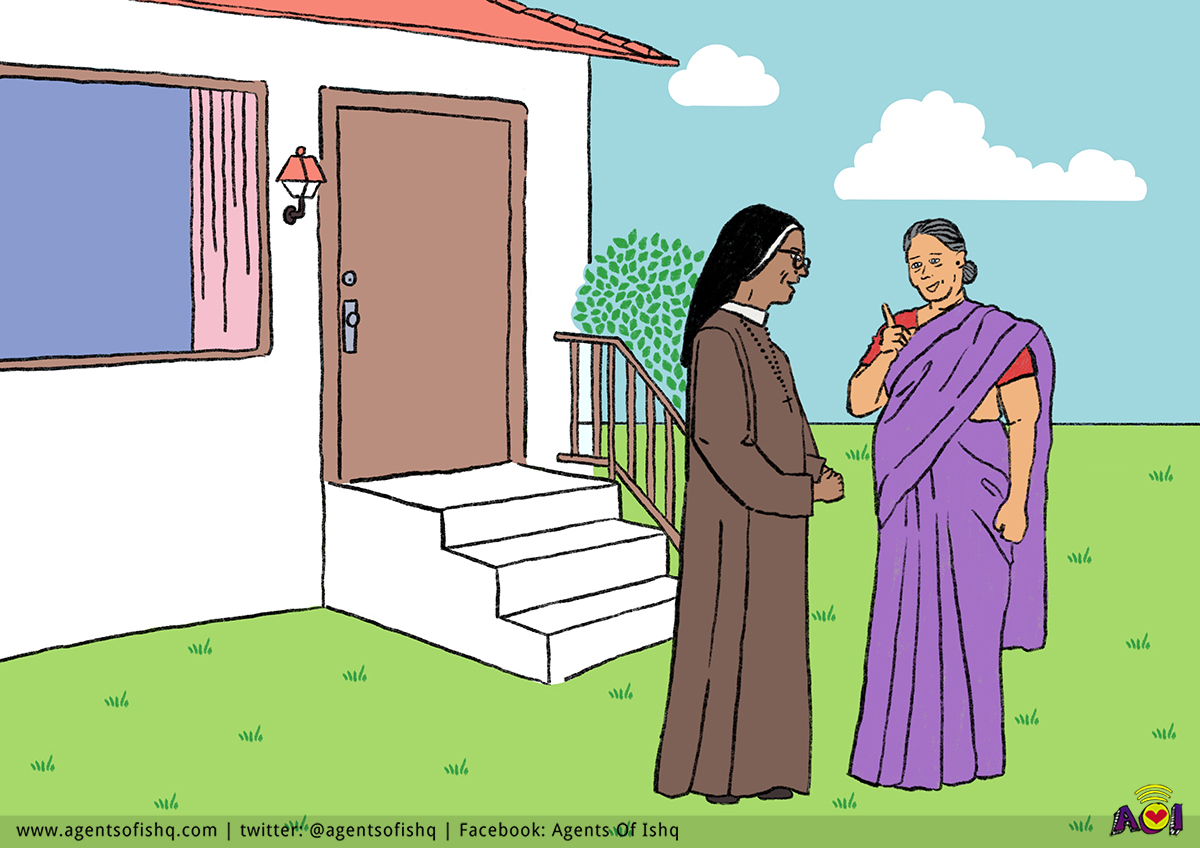

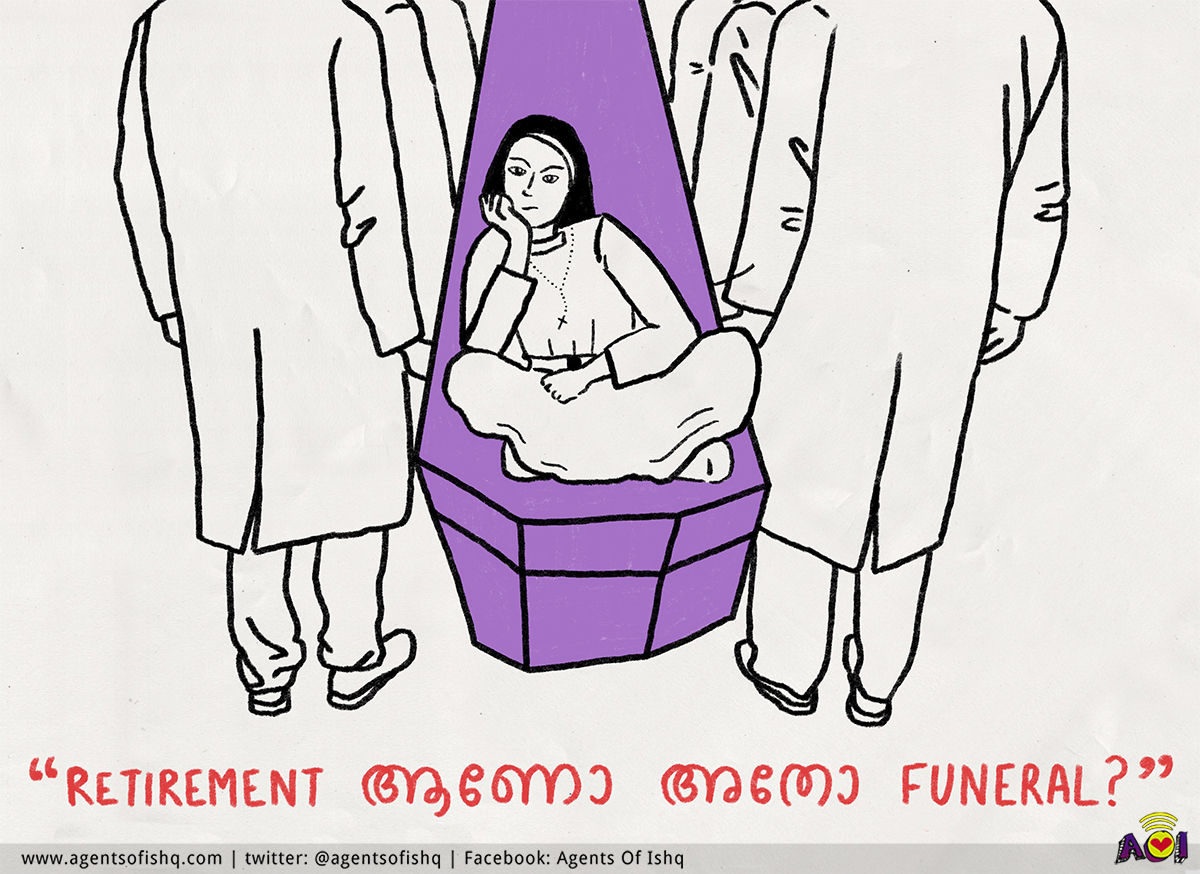

Sister Vimala, though, made very few friends in the convent. She left the convent aged fifty-two because of the abusive treatment meted out to her there. It was hard for me to live within a system of rigid rules, cruelty and jealousy. With a lawyer backing her and substantial pension to live on she was ready for battle. The first time she expressed her desire to leave the convent her companions tried coaxing her out of it. The second time, she was taken to a psychiatrist who deemed her mentally unfit. Initially, my mother stood by me even when others frowned upon my decision. But when the situation worsened, even my ties with amma came loose. Backlash was inevitable and nobody had to warn her. I debated everything and endured all hardships for years before I arrived at my decision. Even then this was a challenging migration and continues to remain so. But nobody can tell me I made a mistake. I was a lecturer alongside and had earnings from that. I know women who want to leave but cannot since they have no jobs or families to support them outside. Though no longer a nun, she still likes to go by the name Sister Vimala. People kept forgetting I had left the convent even when I walked among them in churidar and sarees, out of the nun’s habit. Even my lawyer, the day we finalised the legalities of the process and she was leaving, waved at me from her car and said, “Goodbye and good luck, Sister Vimala!” So I tell everyone I meet to call me Sister Vimala. I like it that way. I always knew about the politics within the convent. I had studied in a college run by nuns. The jealousy, the hierarchies. And the rules have always been different for men and women. Despite these misgivings, she became a nun because she knew God was guiding her through it. Today, I don’t go to church. I don’t say the rosary. I don’t confess. I’ve put my religious life behind me but I am still a spiritual person. I turn to God for comfort even today as I speak out against the church.A man in my hometown left his religious habit. He was welcomed home by his family with open arms. Even my father, who as a young man joined the seminary only to be booted soon after he was caught stealing and drinking Communion wine, today lavishly boasts about his escapades. While many women in my family secretly empathise with Sister Vimala, as my mother does in our kitchen conversations, they too easily dismiss her in public. Sister Vimala uses the word ‘escape’ to describe her departure from the convent. She lives alone now in a flat she bought on loaned money and her pension. The first night after you leave the convent is the most frightening, she tells me. It almost makes you want to turn back. So I always tell the women I meet, “My doors are open to all seeking a temporary abode.” Sister Vimala chose to remain unmarried. But this wasn’t the case for Lillykutty, formerly Sister Alice. For Lillykutty, love led her out of the convent. The young nun eloped with a rubber plantation worker who had been hired by the church. And they never looked back. They now run a popular chayakkada in my hometown. A distant relative, Gladys aunty, too found love as a nun. Forty-two and working as a nurse in Italy, she a lovely older gentleman among her patients swept her off her feet and out of her nun-life too. Back home people love to tee-hee and tell me Gladys aunty-kku lottery adichu, edi (Gladys aunty hit the jackpot). With her lover’s passing, she came into considerable wealth which she now spends on family back in Kerala on her occasional visits from Italy.

I always knew about the politics within the convent. I had studied in a college run by nuns. The jealousy, the hierarchies. And the rules have always been different for men and women. Despite these misgivings, she became a nun because she knew God was guiding her through it. Today, I don’t go to church. I don’t say the rosary. I don’t confess. I’ve put my religious life behind me but I am still a spiritual person. I turn to God for comfort even today as I speak out against the church.A man in my hometown left his religious habit. He was welcomed home by his family with open arms. Even my father, who as a young man joined the seminary only to be booted soon after he was caught stealing and drinking Communion wine, today lavishly boasts about his escapades. While many women in my family secretly empathise with Sister Vimala, as my mother does in our kitchen conversations, they too easily dismiss her in public. Sister Vimala uses the word ‘escape’ to describe her departure from the convent. She lives alone now in a flat she bought on loaned money and her pension. The first night after you leave the convent is the most frightening, she tells me. It almost makes you want to turn back. So I always tell the women I meet, “My doors are open to all seeking a temporary abode.” Sister Vimala chose to remain unmarried. But this wasn’t the case for Lillykutty, formerly Sister Alice. For Lillykutty, love led her out of the convent. The young nun eloped with a rubber plantation worker who had been hired by the church. And they never looked back. They now run a popular chayakkada in my hometown. A distant relative, Gladys aunty, too found love as a nun. Forty-two and working as a nurse in Italy, she a lovely older gentleman among her patients swept her off her feet and out of her nun-life too. Back home people love to tee-hee and tell me Gladys aunty-kku lottery adichu, edi (Gladys aunty hit the jackpot). With her lover’s passing, she came into considerable wealth which she now spends on family back in Kerala on her occasional visits from Italy.  I suppose there’s no word for gold digger in Malayalam. But the adults around me are keen on making up for it with their elaborate descriptions of Gladys aunty and her sayipp (സായിപ്പ്, white man). As a child I knew nothing about being a single woman when I blurted out to people that I did not want to marry. But it turns out that when they joked about me joining the convent, the adults around me knew far less about the women who were nuns, than they did about me. Like the lives of women in a nunnery, the lives of those who left one were also not at all alike.Celine Sister tells me that she’s looking out into her garden of roses while talking to me. Maybe this is my post-retirement hobby. I’m not bragging but I wish you could see the roses. She adds, We know each other now. Call me sometimes like this and we can talk. Now we’re friends, she assures me.

I suppose there’s no word for gold digger in Malayalam. But the adults around me are keen on making up for it with their elaborate descriptions of Gladys aunty and her sayipp (സായിപ്പ്, white man). As a child I knew nothing about being a single woman when I blurted out to people that I did not want to marry. But it turns out that when they joked about me joining the convent, the adults around me knew far less about the women who were nuns, than they did about me. Like the lives of women in a nunnery, the lives of those who left one were also not at all alike.Celine Sister tells me that she’s looking out into her garden of roses while talking to me. Maybe this is my post-retirement hobby. I’m not bragging but I wish you could see the roses. She adds, We know each other now. Call me sometimes like this and we can talk. Now we’re friends, she assures me. In the Malayalam film Jan.E.Man (2021) by Chidambaram, during their father’s funeral, a middle-aged nun is accused by her brother of abandoning her siblings and joining the convent after their mother’s death. She is silent and refuses to apologise. Later it is revealed that in his will, her father has left her some assets should she ever leave the convent and start life afresh. Someone who imagines that a woman does not have to be only one thing, and certainly not one thing forever.

In the Malayalam film Jan.E.Man (2021) by Chidambaram, during their father’s funeral, a middle-aged nun is accused by her brother of abandoning her siblings and joining the convent after their mother’s death. She is silent and refuses to apologise. Later it is revealed that in his will, her father has left her some assets should she ever leave the convent and start life afresh. Someone who imagines that a woman does not have to be only one thing, and certainly not one thing forever. This moment in the film evokes my conversations with the nuns. I set out to write about older nuns but I ended up with stories of women who, each one of them, had the most prosperous personal lives I had encountered in a while. They had rich experiences before they became nuns and even after and beyond it. It seemed foolish to imagine them as an amorphous mass in their habits of grey or brown or salmon. Being a nun, Sister Celine told me, is another way of living. It’s actually just that. Now ask me something else.

This moment in the film evokes my conversations with the nuns. I set out to write about older nuns but I ended up with stories of women who, each one of them, had the most prosperous personal lives I had encountered in a while. They had rich experiences before they became nuns and even after and beyond it. It seemed foolish to imagine them as an amorphous mass in their habits of grey or brown or salmon. Being a nun, Sister Celine told me, is another way of living. It’s actually just that. Now ask me something else.  Nikhita Thomas is still looking for someone to bully her into writing more. She loves a long list of ladies. Her blog, if it arrives some day, will be named Finding Franny. And writing will magically happen on it.

Nikhita Thomas is still looking for someone to bully her into writing more. She loves a long list of ladies. Her blog, if it arrives some day, will be named Finding Franny. And writing will magically happen on it.

At fifteen, the age when the Naomi Campbells and Kate Mosses of the world were scouted by modelling agencies, I was greeted by a pair of nuns who (in some sudden and terrible lapse of judgement, I assumed) felt I’d be a good fit for the religious vocation. I was mildly upset at this proposition. Did I look so prosaic that the only thing I was getting scouted for was the nunnery? I wince now, at my insufferable teenager self.In the second year of college, a soon-to-be seminarian friend suggested I join the convent in order to give him company and proceeded to die laughing at what he believed was a very original joke. Little did he know that me joining the convent was the oldest running joke in my family. Last week, he called me. Among other things he told me about his new friend who was a nun. She had turned forty over the weekend and they had Chinese for lunch at the seminary that day. Her treat, he said.In the category of unmarried woman, nuns reigned supreme and so when a child announced she did not want to get married for reasons she herself did not know, humour was naturally found in imagining the ‘rebel’ child-turned-woman at a convent. If you weren’t going to marry a man, well you must marry God. Single woman? What’s that? When I relate these accounts to Sister Celine, she cackles and lets out with a sigh, Deivame nanni (God, thanks). It appears she is relieved I did not join the convent.

At fifteen, the age when the Naomi Campbells and Kate Mosses of the world were scouted by modelling agencies, I was greeted by a pair of nuns who (in some sudden and terrible lapse of judgement, I assumed) felt I’d be a good fit for the religious vocation. I was mildly upset at this proposition. Did I look so prosaic that the only thing I was getting scouted for was the nunnery? I wince now, at my insufferable teenager self.In the second year of college, a soon-to-be seminarian friend suggested I join the convent in order to give him company and proceeded to die laughing at what he believed was a very original joke. Little did he know that me joining the convent was the oldest running joke in my family. Last week, he called me. Among other things he told me about his new friend who was a nun. She had turned forty over the weekend and they had Chinese for lunch at the seminary that day. Her treat, he said.In the category of unmarried woman, nuns reigned supreme and so when a child announced she did not want to get married for reasons she herself did not know, humour was naturally found in imagining the ‘rebel’ child-turned-woman at a convent. If you weren’t going to marry a man, well you must marry God. Single woman? What’s that? When I relate these accounts to Sister Celine, she cackles and lets out with a sigh, Deivame nanni (God, thanks). It appears she is relieved I did not join the convent.  In 1964 Sister Celine or Celine Sister as I know her left for the convent with five of her classmates. Five from my class of fifteen. We are all nuns today. I ask her what made her want to become a nun. Well, she said, they held a camp on the last day of 10th class. And some of us signed up for it. We knew we were signing up to become nuns but we were also children. So even our best understanding about this commitment was limited. She adds – I too felt like marriage was not for me but that was just at the back of my head. It never occurred to me that I was becoming a nun to escape anything.I spoke to Celine Sister and other nuns with a very straightforward intention: poking my nose into their lives. The Malayalam films I grew up watching cast plain but pleasant women to play their nuns. The nuns on screen all had a certain pained look on their faces. Maybe because they were permanently required to be mild and maternal in a Mother Mary-esque manner. In the childhood relic Ayyappantamma Neyyappam Chuttu (2000), the plump Mother Superior dotes over an orphan child with a very adult name, Monappan. The nun in Priyam (2000) earnestly assists the romance of her best friend. But the nuns I know in real life have little interest in playing mumsy or cupid. My catechism teacher, Sister Beatrice, drove around in her little grey Alto doing errands that, to this day, I know nothing about. The one time she beckoned me warmly towards her I felt special and hoped she would mother me like the film nuns. But we parted ways shortly after she gave me a little talk about the inappropriate length of my shorts. I count this as my first heartbreak. Then there was Sister Grace, determined to spot any kala-pila between the boys and girls and diligently report it to our parents. At least she was honest in that she told us she would do exactly this. She was also prone to poking my ribs from behind with her bony fingers every time I nodded off during Sunday morning mass. I remember many of the nuns from my childhood as strict women with pursed lips because this is all I knew about them. Like the people who made the films I watched, I too had no idea who nuns were when they weren’t a mass in habits. I was always too terrified to ask them.Being asked to go join the convent always felt like a taunt because the picture painted in our jokes was that women in the convent led bland and uninspired lives. Therefore being sent to the convent would prove effective in curbing whatever unruliness denounced marriage in the first place.

In 1964 Sister Celine or Celine Sister as I know her left for the convent with five of her classmates. Five from my class of fifteen. We are all nuns today. I ask her what made her want to become a nun. Well, she said, they held a camp on the last day of 10th class. And some of us signed up for it. We knew we were signing up to become nuns but we were also children. So even our best understanding about this commitment was limited. She adds – I too felt like marriage was not for me but that was just at the back of my head. It never occurred to me that I was becoming a nun to escape anything.I spoke to Celine Sister and other nuns with a very straightforward intention: poking my nose into their lives. The Malayalam films I grew up watching cast plain but pleasant women to play their nuns. The nuns on screen all had a certain pained look on their faces. Maybe because they were permanently required to be mild and maternal in a Mother Mary-esque manner. In the childhood relic Ayyappantamma Neyyappam Chuttu (2000), the plump Mother Superior dotes over an orphan child with a very adult name, Monappan. The nun in Priyam (2000) earnestly assists the romance of her best friend. But the nuns I know in real life have little interest in playing mumsy or cupid. My catechism teacher, Sister Beatrice, drove around in her little grey Alto doing errands that, to this day, I know nothing about. The one time she beckoned me warmly towards her I felt special and hoped she would mother me like the film nuns. But we parted ways shortly after she gave me a little talk about the inappropriate length of my shorts. I count this as my first heartbreak. Then there was Sister Grace, determined to spot any kala-pila between the boys and girls and diligently report it to our parents. At least she was honest in that she told us she would do exactly this. She was also prone to poking my ribs from behind with her bony fingers every time I nodded off during Sunday morning mass. I remember many of the nuns from my childhood as strict women with pursed lips because this is all I knew about them. Like the people who made the films I watched, I too had no idea who nuns were when they weren’t a mass in habits. I was always too terrified to ask them.Being asked to go join the convent always felt like a taunt because the picture painted in our jokes was that women in the convent led bland and uninspired lives. Therefore being sent to the convent would prove effective in curbing whatever unruliness denounced marriage in the first place. If I spoke to the women I wasn’t going to grow up to be, what would I learn?So, I set out to talk to some nuns, and maybe understand a very specific life I might have been expected to lead had I been a young woman in Kerala some decades ago. First, I spoke to Sister Aquinas. Then to Celine Sister. Later to Sister Vimala and others. Now I know two school teachers, a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, the co-owner of a chayakkada and a woman in love. Celine Sister herself is a retired Zoology professor. This year she turns seventy-four. But she tells me that she feels as young as sixty. Do I sound old to you? She asks me over call. I panic a bit but manage a near neutral No…? Exactly! I can feel her beam at me through the phone. That’s what they all tell me. Already I have fallen for this woman.

If I spoke to the women I wasn’t going to grow up to be, what would I learn?So, I set out to talk to some nuns, and maybe understand a very specific life I might have been expected to lead had I been a young woman in Kerala some decades ago. First, I spoke to Sister Aquinas. Then to Celine Sister. Later to Sister Vimala and others. Now I know two school teachers, a doctor, a nurse, a social worker, the co-owner of a chayakkada and a woman in love. Celine Sister herself is a retired Zoology professor. This year she turns seventy-four. But she tells me that she feels as young as sixty. Do I sound old to you? She asks me over call. I panic a bit but manage a near neutral No…? Exactly! I can feel her beam at me through the phone. That’s what they all tell me. Already I have fallen for this woman.  Occasionally Celine Sister interrupts our conversations to remark, But you must already know that about me, no? She is referring to her teaching years and the many adults I know who have studied under her. But the truth is, I know very little about Celine Sister as a teacher. I knew her for her frequent presence at funerals in the family. Weddings not so much. I knew her as chatty but not with me. I knew her only as a nun and of that identity too, I knew very little. Later, on another call, I ask the seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas at what point she started thinking of herself as an older woman. Well, not until now, she says with some amusement. I don’t consider myself old. But if you think I am, I suppose I must be old, alle? Feeling very sheepish, I make a quick and clumsy U-turn into the past. When Sister Aquinas talks about herself, she too shies away from any categorical understanding of her life. I ask her about the motivations behind her decision to become a nun. Did I not want to get married? Is that what you’re asking me? she asks me. I believe I became a nun because God called me to it. If I simply wanted to avoid marriage, I could not have remained long within the Church. Girls are confident now. There are many women who neither join the convent nor marry. They don’t have time for either. They might be happy. They might not be happy. I don’t know. I can tell you how it has been for me.In Kerala, and I’m sure elsewhere too, the word ‘Sister’ can be employed in an abundance of situations. In hospitals Sisters are nurses who look after you. At the church they are the nuns who look over you. More infrequently, the term ‘sister’ is actually used to address one’s sibling. Maybe because ‘sister’ is a word loaded with meanings of caregiving and kinship, I was given to assumptions about the maternal bearing of nuns. Or maybe because of how easy it is to think about women in terms of these divisions – married and single, caring and uncaring. As, the sisters – the nuns - spoke of themselves they slipped effortlessly out of the girdle of maternal instincts regularly expected of women, whether they reproduce or not.Celine Sister is a teacher first and everything else after that – I know this sounds unbelievable but when I step onto the podium of my classroom, I am possessed by some spirit. Outside the classroom I am a friend to my students. Inside it they are not my biggest fans but the feeling is mutual. When I bring up her nun-hood, she expertly guides me back into her classroom. It reminded me of an incident from college when a friend told a professor that she was like a mother to all of us. She winced and shot back with lots of feelings, Yuck.

Occasionally Celine Sister interrupts our conversations to remark, But you must already know that about me, no? She is referring to her teaching years and the many adults I know who have studied under her. But the truth is, I know very little about Celine Sister as a teacher. I knew her for her frequent presence at funerals in the family. Weddings not so much. I knew her as chatty but not with me. I knew her only as a nun and of that identity too, I knew very little. Later, on another call, I ask the seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas at what point she started thinking of herself as an older woman. Well, not until now, she says with some amusement. I don’t consider myself old. But if you think I am, I suppose I must be old, alle? Feeling very sheepish, I make a quick and clumsy U-turn into the past. When Sister Aquinas talks about herself, she too shies away from any categorical understanding of her life. I ask her about the motivations behind her decision to become a nun. Did I not want to get married? Is that what you’re asking me? she asks me. I believe I became a nun because God called me to it. If I simply wanted to avoid marriage, I could not have remained long within the Church. Girls are confident now. There are many women who neither join the convent nor marry. They don’t have time for either. They might be happy. They might not be happy. I don’t know. I can tell you how it has been for me.In Kerala, and I’m sure elsewhere too, the word ‘Sister’ can be employed in an abundance of situations. In hospitals Sisters are nurses who look after you. At the church they are the nuns who look over you. More infrequently, the term ‘sister’ is actually used to address one’s sibling. Maybe because ‘sister’ is a word loaded with meanings of caregiving and kinship, I was given to assumptions about the maternal bearing of nuns. Or maybe because of how easy it is to think about women in terms of these divisions – married and single, caring and uncaring. As, the sisters – the nuns - spoke of themselves they slipped effortlessly out of the girdle of maternal instincts regularly expected of women, whether they reproduce or not.Celine Sister is a teacher first and everything else after that – I know this sounds unbelievable but when I step onto the podium of my classroom, I am possessed by some spirit. Outside the classroom I am a friend to my students. Inside it they are not my biggest fans but the feeling is mutual. When I bring up her nun-hood, she expertly guides me back into her classroom. It reminded me of an incident from college when a friend told a professor that she was like a mother to all of us. She winced and shot back with lots of feelings, Yuck. In our conversations, Sister Aquinas frequently returns to her friendships both inside and outside the congregation. My companions and I travel together. They have accompanied me across the country. And I feel like all the travelling I’ve done is nothing short of a blessing. It comes with my vocation. She adds, You know, I have grown to like being an older nun. It means more respect, more esteem and I’m not mad at all. She speaks fondly of her friends back home, many of them who continued to visit her even after she left for the convent. Nothing much has changed. They have their families. And I too have my work. But we have our childhoods in common. No two nuns were alike. But nearly all the nuns flitted uncomfortably at the mention of that sinister creature, the single woman. Did you not feel confident as a young woman? I ask Sister Aquinas in response to her feelings about girls now. Her response is quick – It did require confidence to leave home and join the convent. Even today. But being a single woman comes with consequences. From your own family and from society. Frankly, it’s an uphill battle. Besides, it was not ‘single’ I was trying to be.None of the stories lingered even accidentally over their single women aka unmarried statuses. Their stance is a very Yes, we are unmarried. And what about it? And I too begin wondering – Yeah, no? What about it?And yet, in another universe, Celine Sister might not have joined the convent, she says. All my friends were going. I just went along. It was just like school. Except we studied to become nuns along with other subjects. Homesickness in the first month. Crying to sleep through the nights. The occasional parent or sibling who visited her. She tells me she was never particularly pious. I was never the girl who went for mass regularly. Nobody knew me for my godliness. But in the end, I was the one who ended up a nun! She tells me she loves being a nun because it is an extension of her teaching. Some people cannot see that I really do enjoy my job, even at my age, Sister Celine says. I am now in my seventies but I keep myself busy. I sew, I mend and I garden. I still teach and still have duties to discharge. And you know what? I wouldn’t change a thing. For Sister Aquinas too, being a nun exists alongside her line of work as a social worker.. In fact, the religious vocation often enables and is a conduit for her profession. Born into an aristocrat family, Sister Aquinas laughs when she tells me she did not want to make the rich any richer. She quickly adds, now don’t go write about me like I’m some communist nun. It’s a cliche, she says, but I became a nun because I really did have a calling. Celine Sister is a Mohanlal fan. When I was a hostel warden I used to take my kids to the movies nearly every weekend, she says. And we never missed anything with Mohanlal in it. Later I ask seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas to pick between Mammooty and Mohanlal. Neither. Sathyan is my hero. What about Prem Nazir? I ask her. She briefly considers the option. No, not him. He was always just walking around singing. The Malayalam word for nun is kanyasthree (കന്യാസ്ത്രീ). It is one of those words which when translated into English tend to sound somewhat abysmal — virgin woman. I’m petrified to bring up celibacy in conversation. But I attempt to make a clean segue from Mohanlal and Sathyan to their sexual desires and fantasies growing up.

In our conversations, Sister Aquinas frequently returns to her friendships both inside and outside the congregation. My companions and I travel together. They have accompanied me across the country. And I feel like all the travelling I’ve done is nothing short of a blessing. It comes with my vocation. She adds, You know, I have grown to like being an older nun. It means more respect, more esteem and I’m not mad at all. She speaks fondly of her friends back home, many of them who continued to visit her even after she left for the convent. Nothing much has changed. They have their families. And I too have my work. But we have our childhoods in common. No two nuns were alike. But nearly all the nuns flitted uncomfortably at the mention of that sinister creature, the single woman. Did you not feel confident as a young woman? I ask Sister Aquinas in response to her feelings about girls now. Her response is quick – It did require confidence to leave home and join the convent. Even today. But being a single woman comes with consequences. From your own family and from society. Frankly, it’s an uphill battle. Besides, it was not ‘single’ I was trying to be.None of the stories lingered even accidentally over their single women aka unmarried statuses. Their stance is a very Yes, we are unmarried. And what about it? And I too begin wondering – Yeah, no? What about it?And yet, in another universe, Celine Sister might not have joined the convent, she says. All my friends were going. I just went along. It was just like school. Except we studied to become nuns along with other subjects. Homesickness in the first month. Crying to sleep through the nights. The occasional parent or sibling who visited her. She tells me she was never particularly pious. I was never the girl who went for mass regularly. Nobody knew me for my godliness. But in the end, I was the one who ended up a nun! She tells me she loves being a nun because it is an extension of her teaching. Some people cannot see that I really do enjoy my job, even at my age, Sister Celine says. I am now in my seventies but I keep myself busy. I sew, I mend and I garden. I still teach and still have duties to discharge. And you know what? I wouldn’t change a thing. For Sister Aquinas too, being a nun exists alongside her line of work as a social worker.. In fact, the religious vocation often enables and is a conduit for her profession. Born into an aristocrat family, Sister Aquinas laughs when she tells me she did not want to make the rich any richer. She quickly adds, now don’t go write about me like I’m some communist nun. It’s a cliche, she says, but I became a nun because I really did have a calling. Celine Sister is a Mohanlal fan. When I was a hostel warden I used to take my kids to the movies nearly every weekend, she says. And we never missed anything with Mohanlal in it. Later I ask seventy-year-old Sister Aquinas to pick between Mammooty and Mohanlal. Neither. Sathyan is my hero. What about Prem Nazir? I ask her. She briefly considers the option. No, not him. He was always just walking around singing. The Malayalam word for nun is kanyasthree (കന്യാസ്ത്രീ). It is one of those words which when translated into English tend to sound somewhat abysmal — virgin woman. I’m petrified to bring up celibacy in conversation. But I attempt to make a clean segue from Mohanlal and Sathyan to their sexual desires and fantasies growing up. Sister Aquinas says she won’t lie. I went for confession. And if that didn’t work, I would cry. Sometimes when I was overcome with feelings, I went into the chapel and had a good cry. It always made me feel better. Sister Celine tells me, It’s normal that we too have human feelings. But the point is that I overcome all obstacles. She says that Mother Mary is her go to lady. Sister Aquinas recalls an early interaction with her mother before joining the convent. My mother took me to a statue of Mother Mary outside our church and told me I couldn’t cling onto her anymore. Mother Mary would be my substitute mother. And that’s how it’s been since then.Sister Aquinas insists that she would not have remained in the convent if it weren’t for the older nuns who understood her as a young girl. We are all companions in the convent, old and young, says Sister Celine. You know, we are all busy women. More than you’d imagine. Pockets of friendship formed in their brief interactions with the mutual understanding that companionship was nearly always temporary owing to their vocation.

Sister Aquinas says she won’t lie. I went for confession. And if that didn’t work, I would cry. Sometimes when I was overcome with feelings, I went into the chapel and had a good cry. It always made me feel better. Sister Celine tells me, It’s normal that we too have human feelings. But the point is that I overcome all obstacles. She says that Mother Mary is her go to lady. Sister Aquinas recalls an early interaction with her mother before joining the convent. My mother took me to a statue of Mother Mary outside our church and told me I couldn’t cling onto her anymore. Mother Mary would be my substitute mother. And that’s how it’s been since then.Sister Aquinas insists that she would not have remained in the convent if it weren’t for the older nuns who understood her as a young girl. We are all companions in the convent, old and young, says Sister Celine. You know, we are all busy women. More than you’d imagine. Pockets of friendship formed in their brief interactions with the mutual understanding that companionship was nearly always temporary owing to their vocation. Sister Vimala, though, made very few friends in the convent. She left the convent aged fifty-two because of the abusive treatment meted out to her there. It was hard for me to live within a system of rigid rules, cruelty and jealousy. With a lawyer backing her and substantial pension to live on she was ready for battle. The first time she expressed her desire to leave the convent her companions tried coaxing her out of it. The second time, she was taken to a psychiatrist who deemed her mentally unfit. Initially, my mother stood by me even when others frowned upon my decision. But when the situation worsened, even my ties with amma came loose. Backlash was inevitable and nobody had to warn her. I debated everything and endured all hardships for years before I arrived at my decision. Even then this was a challenging migration and continues to remain so. But nobody can tell me I made a mistake. I was a lecturer alongside and had earnings from that. I know women who want to leave but cannot since they have no jobs or families to support them outside. Though no longer a nun, she still likes to go by the name Sister Vimala. People kept forgetting I had left the convent even when I walked among them in churidar and sarees, out of the nun’s habit. Even my lawyer, the day we finalised the legalities of the process and she was leaving, waved at me from her car and said, “Goodbye and good luck, Sister Vimala!” So I tell everyone I meet to call me Sister Vimala. I like it that way.

Sister Vimala, though, made very few friends in the convent. She left the convent aged fifty-two because of the abusive treatment meted out to her there. It was hard for me to live within a system of rigid rules, cruelty and jealousy. With a lawyer backing her and substantial pension to live on she was ready for battle. The first time she expressed her desire to leave the convent her companions tried coaxing her out of it. The second time, she was taken to a psychiatrist who deemed her mentally unfit. Initially, my mother stood by me even when others frowned upon my decision. But when the situation worsened, even my ties with amma came loose. Backlash was inevitable and nobody had to warn her. I debated everything and endured all hardships for years before I arrived at my decision. Even then this was a challenging migration and continues to remain so. But nobody can tell me I made a mistake. I was a lecturer alongside and had earnings from that. I know women who want to leave but cannot since they have no jobs or families to support them outside. Though no longer a nun, she still likes to go by the name Sister Vimala. People kept forgetting I had left the convent even when I walked among them in churidar and sarees, out of the nun’s habit. Even my lawyer, the day we finalised the legalities of the process and she was leaving, waved at me from her car and said, “Goodbye and good luck, Sister Vimala!” So I tell everyone I meet to call me Sister Vimala. I like it that way. I always knew about the politics within the convent. I had studied in a college run by nuns. The jealousy, the hierarchies. And the rules have always been different for men and women. Despite these misgivings, she became a nun because she knew God was guiding her through it. Today, I don’t go to church. I don’t say the rosary. I don’t confess. I’ve put my religious life behind me but I am still a spiritual person. I turn to God for comfort even today as I speak out against the church.A man in my hometown left his religious habit. He was welcomed home by his family with open arms. Even my father, who as a young man joined the seminary only to be booted soon after he was caught stealing and drinking Communion wine, today lavishly boasts about his escapades. While many women in my family secretly empathise with Sister Vimala, as my mother does in our kitchen conversations, they too easily dismiss her in public. Sister Vimala uses the word ‘escape’ to describe her departure from the convent. She lives alone now in a flat she bought on loaned money and her pension. The first night after you leave the convent is the most frightening, she tells me. It almost makes you want to turn back. So I always tell the women I meet, “My doors are open to all seeking a temporary abode.” Sister Vimala chose to remain unmarried. But this wasn’t the case for Lillykutty, formerly Sister Alice. For Lillykutty, love led her out of the convent. The young nun eloped with a rubber plantation worker who had been hired by the church. And they never looked back. They now run a popular chayakkada in my hometown. A distant relative, Gladys aunty, too found love as a nun. Forty-two and working as a nurse in Italy, she a lovely older gentleman among her patients swept her off her feet and out of her nun-life too. Back home people love to tee-hee and tell me Gladys aunty-kku lottery adichu, edi (Gladys aunty hit the jackpot). With her lover’s passing, she came into considerable wealth which she now spends on family back in Kerala on her occasional visits from Italy.

I always knew about the politics within the convent. I had studied in a college run by nuns. The jealousy, the hierarchies. And the rules have always been different for men and women. Despite these misgivings, she became a nun because she knew God was guiding her through it. Today, I don’t go to church. I don’t say the rosary. I don’t confess. I’ve put my religious life behind me but I am still a spiritual person. I turn to God for comfort even today as I speak out against the church.A man in my hometown left his religious habit. He was welcomed home by his family with open arms. Even my father, who as a young man joined the seminary only to be booted soon after he was caught stealing and drinking Communion wine, today lavishly boasts about his escapades. While many women in my family secretly empathise with Sister Vimala, as my mother does in our kitchen conversations, they too easily dismiss her in public. Sister Vimala uses the word ‘escape’ to describe her departure from the convent. She lives alone now in a flat she bought on loaned money and her pension. The first night after you leave the convent is the most frightening, she tells me. It almost makes you want to turn back. So I always tell the women I meet, “My doors are open to all seeking a temporary abode.” Sister Vimala chose to remain unmarried. But this wasn’t the case for Lillykutty, formerly Sister Alice. For Lillykutty, love led her out of the convent. The young nun eloped with a rubber plantation worker who had been hired by the church. And they never looked back. They now run a popular chayakkada in my hometown. A distant relative, Gladys aunty, too found love as a nun. Forty-two and working as a nurse in Italy, she a lovely older gentleman among her patients swept her off her feet and out of her nun-life too. Back home people love to tee-hee and tell me Gladys aunty-kku lottery adichu, edi (Gladys aunty hit the jackpot). With her lover’s passing, she came into considerable wealth which she now spends on family back in Kerala on her occasional visits from Italy.  I suppose there’s no word for gold digger in Malayalam. But the adults around me are keen on making up for it with their elaborate descriptions of Gladys aunty and her sayipp (സായിപ്പ്, white man). As a child I knew nothing about being a single woman when I blurted out to people that I did not want to marry. But it turns out that when they joked about me joining the convent, the adults around me knew far less about the women who were nuns, than they did about me. Like the lives of women in a nunnery, the lives of those who left one were also not at all alike.Celine Sister tells me that she’s looking out into her garden of roses while talking to me. Maybe this is my post-retirement hobby. I’m not bragging but I wish you could see the roses. She adds, We know each other now. Call me sometimes like this and we can talk. Now we’re friends, she assures me.

I suppose there’s no word for gold digger in Malayalam. But the adults around me are keen on making up for it with their elaborate descriptions of Gladys aunty and her sayipp (സായിപ്പ്, white man). As a child I knew nothing about being a single woman when I blurted out to people that I did not want to marry. But it turns out that when they joked about me joining the convent, the adults around me knew far less about the women who were nuns, than they did about me. Like the lives of women in a nunnery, the lives of those who left one were also not at all alike.Celine Sister tells me that she’s looking out into her garden of roses while talking to me. Maybe this is my post-retirement hobby. I’m not bragging but I wish you could see the roses. She adds, We know each other now. Call me sometimes like this and we can talk. Now we’re friends, she assures me. In the Malayalam film Jan.E.Man (2021) by Chidambaram, during their father’s funeral, a middle-aged nun is accused by her brother of abandoning her siblings and joining the convent after their mother’s death. She is silent and refuses to apologise. Later it is revealed that in his will, her father has left her some assets should she ever leave the convent and start life afresh. Someone who imagines that a woman does not have to be only one thing, and certainly not one thing forever.

In the Malayalam film Jan.E.Man (2021) by Chidambaram, during their father’s funeral, a middle-aged nun is accused by her brother of abandoning her siblings and joining the convent after their mother’s death. She is silent and refuses to apologise. Later it is revealed that in his will, her father has left her some assets should she ever leave the convent and start life afresh. Someone who imagines that a woman does not have to be only one thing, and certainly not one thing forever. This moment in the film evokes my conversations with the nuns. I set out to write about older nuns but I ended up with stories of women who, each one of them, had the most prosperous personal lives I had encountered in a while. They had rich experiences before they became nuns and even after and beyond it. It seemed foolish to imagine them as an amorphous mass in their habits of grey or brown or salmon. Being a nun, Sister Celine told me, is another way of living. It’s actually just that. Now ask me something else.

This moment in the film evokes my conversations with the nuns. I set out to write about older nuns but I ended up with stories of women who, each one of them, had the most prosperous personal lives I had encountered in a while. They had rich experiences before they became nuns and even after and beyond it. It seemed foolish to imagine them as an amorphous mass in their habits of grey or brown or salmon. Being a nun, Sister Celine told me, is another way of living. It’s actually just that. Now ask me something else.  Nikhita Thomas is still looking for someone to bully her into writing more. She loves a long list of ladies. Her blog, if it arrives some day, will be named Finding Franny. And writing will magically happen on it.

Nikhita Thomas is still looking for someone to bully her into writing more. She loves a long list of ladies. Her blog, if it arrives some day, will be named Finding Franny. And writing will magically happen on it.