Ever since I started reading Urdu poetry, I had noticed something unusual about ghazals. They often spoke of a beloved, but why was this beloved always genderless? It was something that left me baffled for a long time.Because Urdu poetry – also known as Rekhta – in the past was written largely by men, and the gender of the lover is not always clear, we tend to assume that the beloved that they celebrated or pined for was a woman. But a closer look at the ghazal shows a fascinating range – some poets, like Mir, wrote about a male beloved too. Within the genre of Rekhti poetry, ghazals use a female voice to speak about the female beloved. And Saraapa, a subgenre of Rekhti, focuses on parts of the body. Studying the work of Urdu ghazal poets showed me that their approach to sexual desire is far more fluid than I had realised.Although there is a plethora of writing on Urdu poetry, the queer aspects of it aren’t discussed much, even in contemporary writing on the Indian subcontinent. For a long time, I thought that the absence of women, and the lack of representation of multiple sexualities in Urdu poetry was perhaps a function of its Islamic origins – Islam, like Christianity and any other monolithic religion, condemns homosexuality in the strictest of terms. But, as it turns out, I was wrong – really wrong! The ghazal originated in the Arabian peninsula during the 8th century, from where it spread to Persia, leading to the creation of the Persian ghazal. The modern Urdu ghazal is a love-child born out of cultural wedlock to a Persian father and an Indian mother. Its aesthetics are derived from Perso-Arabic Islamicate literature, including the gender of the proverbial ‘maashuq’ (beloved), which, in most cases, is grammatically gender neutral and the identity of the beloved could be either male or female. This is largely because of the Persian traditions which Urdu poetry inherited, as grammatically, in the Persian language, there is no clear distinction between male and female verbs or pronouns, and gender is impossible to determine from the construction of the sentence. Consider the following couplet by Ghalib:Yeh na thi hamari qismat ke visal-e yar hotaAgar aur jeete rahte yahi intizaar hota(It was not my fate to unite with the Beloved;Yet had I gone on living, I’d have kept up this same waiting)Now, in this couplet, even though the gender of the Beloved (yar) is grammatically masculine, it's gender neutral, yar, could mean either a female or a male.

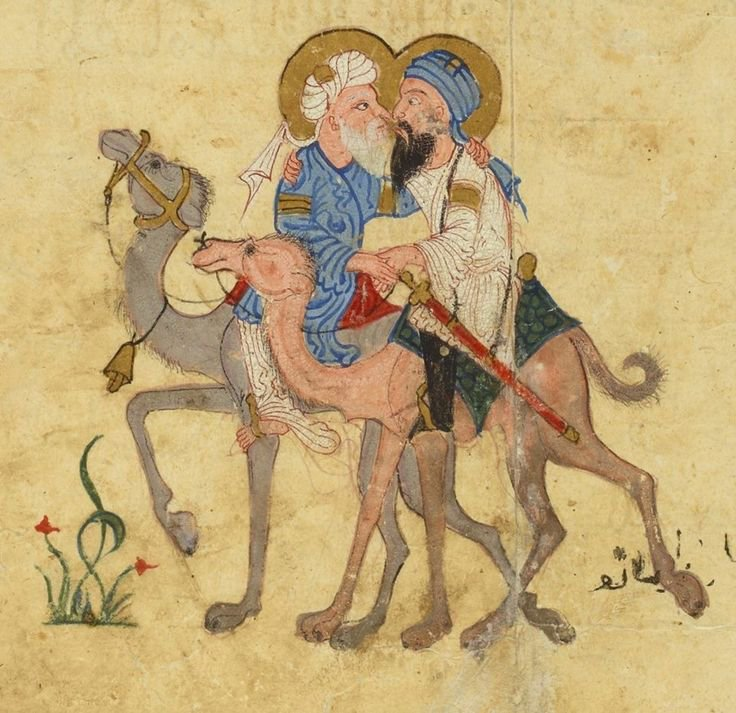

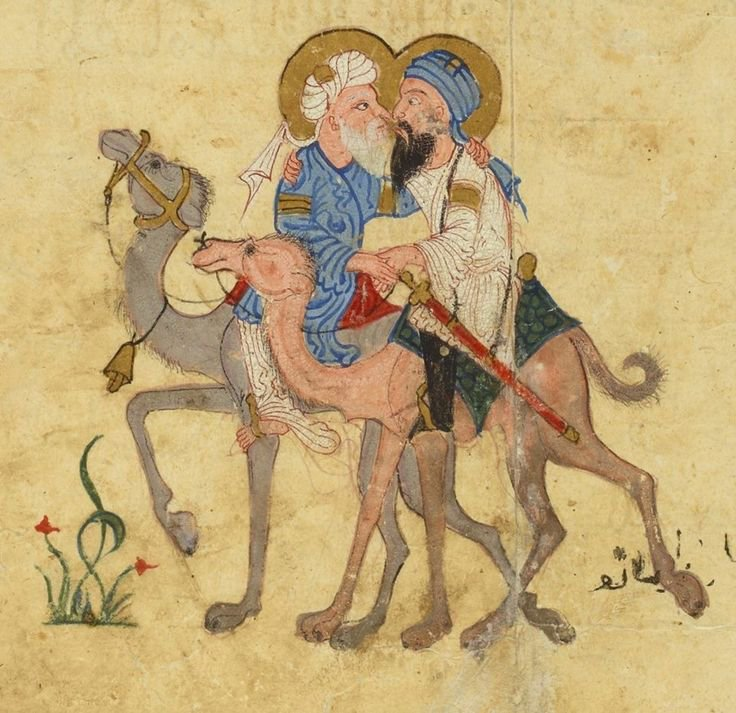

The ghazal originated in the Arabian peninsula during the 8th century, from where it spread to Persia, leading to the creation of the Persian ghazal. The modern Urdu ghazal is a love-child born out of cultural wedlock to a Persian father and an Indian mother. Its aesthetics are derived from Perso-Arabic Islamicate literature, including the gender of the proverbial ‘maashuq’ (beloved), which, in most cases, is grammatically gender neutral and the identity of the beloved could be either male or female. This is largely because of the Persian traditions which Urdu poetry inherited, as grammatically, in the Persian language, there is no clear distinction between male and female verbs or pronouns, and gender is impossible to determine from the construction of the sentence. Consider the following couplet by Ghalib:Yeh na thi hamari qismat ke visal-e yar hotaAgar aur jeete rahte yahi intizaar hota(It was not my fate to unite with the Beloved;Yet had I gone on living, I’d have kept up this same waiting)Now, in this couplet, even though the gender of the Beloved (yar) is grammatically masculine, it's gender neutral, yar, could mean either a female or a male.  While not all Urdu poets wrote extensively on homosexual themes, there’s no dearth of poets with heterosexual identities who fancied young adolescent boys – though we don’t know if this desire translated into actual relationships. In the following couplet, Ghalib writes:Aamad-e-Khat se hua hay sard jo bazar-e-dostdood-e-shama-e-kushta tha shaid khat-e-rukhsar-e-dost(With the sprouting of the beard, demand for my beloved has diminished.Now it appears like the smoke of a dying fire.)(Today, we might view a relationship between an older man and a young boy far less benevolently but these poems belong to a time of rather different mores.) This tradition of love towards young boys dates back to early Islamic world of Arabia and Persia, where it was a common practice to have a young male lover. Important figures in the history of the ghazal, like the 8th century Persian poet Abu Nuwas and the 14th century Arab poet Nawaji Bin Hasan, also known as "Shams al-Din" or Sun Of Religion, wrote extensively on male homoerotic themes, where the beloved is a young boy who recently attained puberty. Homosexual love has always been a part of the ghazal’s history. But in India, it wasn’t until the late 19th century, when British Victorian mindsets around sexuality began to take root, that homosexual themes began to disappear from the Urdu ghazal. Barring the 20th century poets Firaaq Gorakhpuri (1896-1982) and Josh Malihabadi (1894-1982), whose homosexual relationships in their poetry and in their personal lives were widely known, there are hardly any examples from the recent past.However, although they are the most quoted and well-known, men who desire other men or boys don’t form the only kind of queer voice in the Urdu ghazal.

While not all Urdu poets wrote extensively on homosexual themes, there’s no dearth of poets with heterosexual identities who fancied young adolescent boys – though we don’t know if this desire translated into actual relationships. In the following couplet, Ghalib writes:Aamad-e-Khat se hua hay sard jo bazar-e-dostdood-e-shama-e-kushta tha shaid khat-e-rukhsar-e-dost(With the sprouting of the beard, demand for my beloved has diminished.Now it appears like the smoke of a dying fire.)(Today, we might view a relationship between an older man and a young boy far less benevolently but these poems belong to a time of rather different mores.) This tradition of love towards young boys dates back to early Islamic world of Arabia and Persia, where it was a common practice to have a young male lover. Important figures in the history of the ghazal, like the 8th century Persian poet Abu Nuwas and the 14th century Arab poet Nawaji Bin Hasan, also known as "Shams al-Din" or Sun Of Religion, wrote extensively on male homoerotic themes, where the beloved is a young boy who recently attained puberty. Homosexual love has always been a part of the ghazal’s history. But in India, it wasn’t until the late 19th century, when British Victorian mindsets around sexuality began to take root, that homosexual themes began to disappear from the Urdu ghazal. Barring the 20th century poets Firaaq Gorakhpuri (1896-1982) and Josh Malihabadi (1894-1982), whose homosexual relationships in their poetry and in their personal lives were widely known, there are hardly any examples from the recent past.However, although they are the most quoted and well-known, men who desire other men or boys don’t form the only kind of queer voice in the Urdu ghazal. Insha Allah Khan “Insha” (1756-1817), another prolific Rekhti poet, wrote extensively on lesbian love. Take the following verses, for example: Aag lene ko jo aayin to kahin laag lagaBibi hamsaai ne di jee men meri aag lagaNa bura mane to lun noch ko’ī muthi bharBegama har teri kyaari men hara sag laga(When she came to take fire, an attraction took hold;The neighbor lady lit a fire in my heartIf you don’t mind, may I seize a handful or two?Young lady, greens grow in every bed of yours!)Jan Sahib (1810-1886) wrote about sexual fantasies – not necessarily homo-erotic – with a playfull naughtiness: Le chuka munh me hai lallu meri sau bar zubaanho gaya kab ka musalmaan, ye kya kaafir hai.(He has sucked my tongue many a time, this lalluHe has long been a Muslim – he's no kafir.)Zaal to beshak hai tu, beta agar rustam nahinbhaar do do joru'on ka aur kamar me kham nahin.(You are certainly a Zaal, if not in fact a Rustam!You serve two wives, but your back isn't bent.)Another subgenre of Rekhti called ‘Saraapa’, which literally means ‘head to toe’, is one in which the poet writes about various parts of the body. Here’s Ju’rrat describing feet of his beloved:Aur jo hathon men utha lun to ajab lutf uthaaonPhir jo vo lutf uthana tujhe bitha ke dikhlaaon.(And if I lift the feet I would find a strange pleasureAnd then to make you sit and watch that pleasure-taking.)Or, this couplet where he talks about buttocks and thighs:Koh-e sureen dekho to sar phodo tumRanen makhmal si hain khvab-o-khurus chodo tum(And if you see the mountains of the derriere you would knock out your headAnd the thighs are like satin – make you leave all dreaming and thinking)

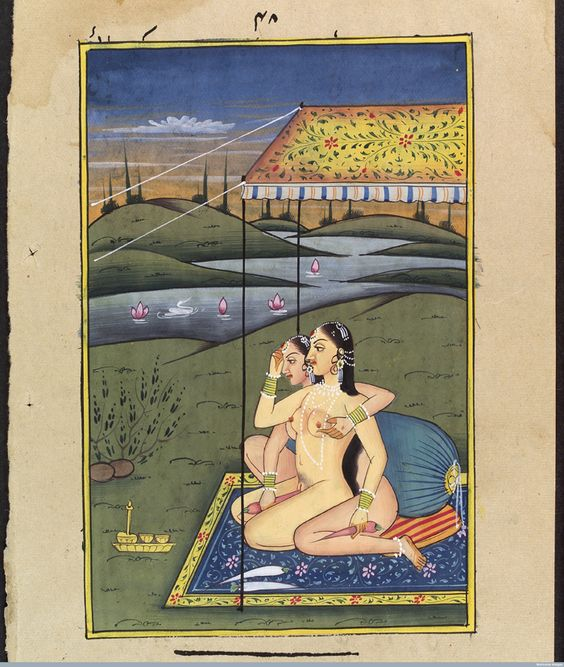

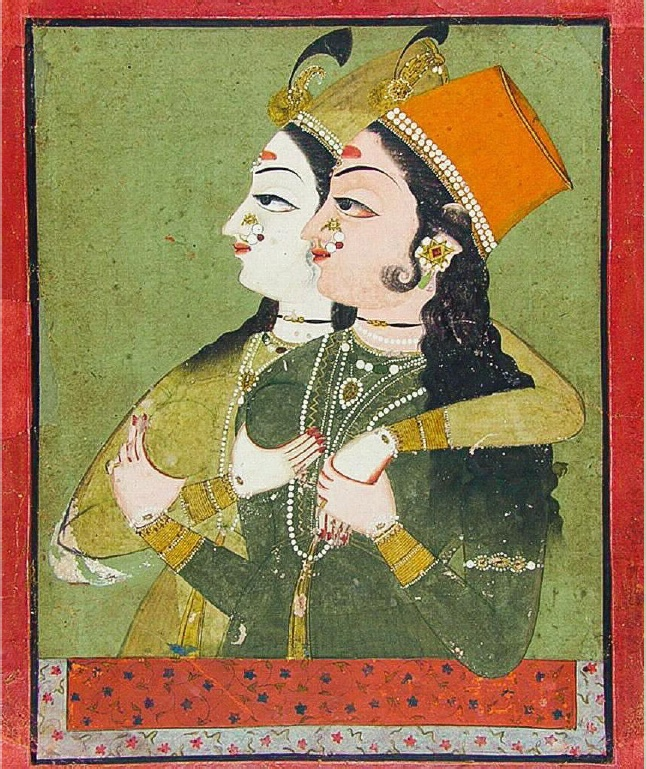

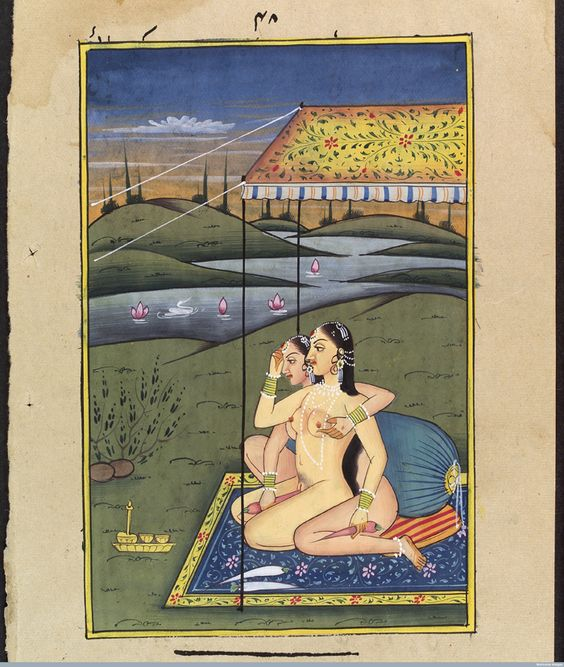

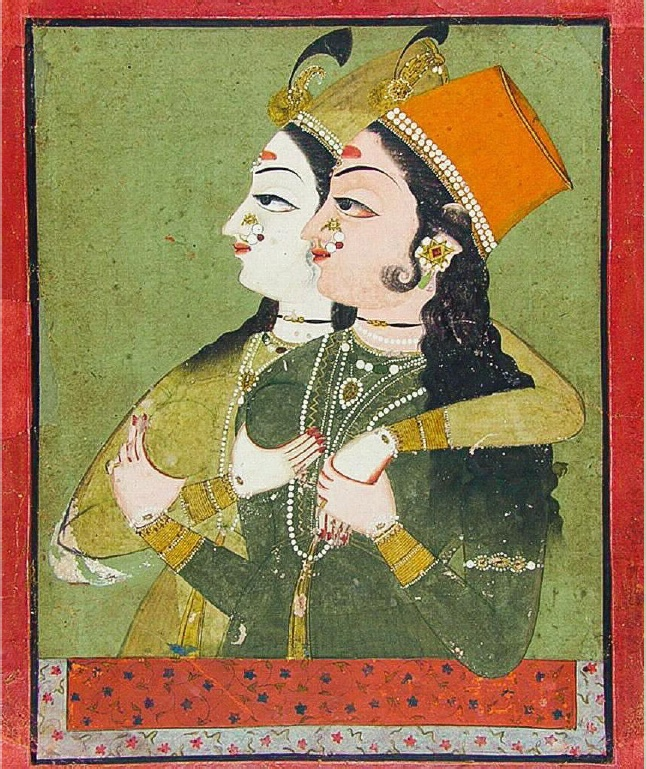

Insha Allah Khan “Insha” (1756-1817), another prolific Rekhti poet, wrote extensively on lesbian love. Take the following verses, for example: Aag lene ko jo aayin to kahin laag lagaBibi hamsaai ne di jee men meri aag lagaNa bura mane to lun noch ko’ī muthi bharBegama har teri kyaari men hara sag laga(When she came to take fire, an attraction took hold;The neighbor lady lit a fire in my heartIf you don’t mind, may I seize a handful or two?Young lady, greens grow in every bed of yours!)Jan Sahib (1810-1886) wrote about sexual fantasies – not necessarily homo-erotic – with a playfull naughtiness: Le chuka munh me hai lallu meri sau bar zubaanho gaya kab ka musalmaan, ye kya kaafir hai.(He has sucked my tongue many a time, this lalluHe has long been a Muslim – he's no kafir.)Zaal to beshak hai tu, beta agar rustam nahinbhaar do do joru'on ka aur kamar me kham nahin.(You are certainly a Zaal, if not in fact a Rustam!You serve two wives, but your back isn't bent.)Another subgenre of Rekhti called ‘Saraapa’, which literally means ‘head to toe’, is one in which the poet writes about various parts of the body. Here’s Ju’rrat describing feet of his beloved:Aur jo hathon men utha lun to ajab lutf uthaaonPhir jo vo lutf uthana tujhe bitha ke dikhlaaon.(And if I lift the feet I would find a strange pleasureAnd then to make you sit and watch that pleasure-taking.)Or, this couplet where he talks about buttocks and thighs:Koh-e sureen dekho to sar phodo tumRanen makhmal si hain khvab-o-khurus chodo tum(And if you see the mountains of the derriere you would knock out your headAnd the thighs are like satin – make you leave all dreaming and thinking) Here’s another example, and this is perhaps the most poetic description of a vagina I have ever read:Aur kyaa is ke sivaa kijiye midhat us kiDo hilal ik jagah dekhe hain qudrat us ki.(What other praise can I lavish upon itTwo crescent moons were seen at one place – God be praised!)It’s only when you uncover these poetic gems that you realise what colonial occupation has done to suppress our literary heritage. These queer genres within Urdu poetry deserve a wider audience. Love – homosexual or otherwise, knows no bounds. Love is like that Greek quote – “What you didn’t do to bury me/But you forgot that I was a seed” – by the 20th century poet Dinos Christianopoulos, who was denounced by the literary community because of his (homo)sexual orientation. Sometimes, I like to think of love as a wildland fire on an empty landscape. A fire within fire, a hope within hope. It defies the topology of the region, the way poetry defies religious and social norms.Or as Ghalib would say, “Ishq par zor nahin, hai ye wo aatish Ghalib”!Salik heads the Social Media Communications (aka Ghalib-in-Chief) at Talk Journalism and he can be found tweeting about Poetry, Physics and Ghalib @baawraman

Here’s another example, and this is perhaps the most poetic description of a vagina I have ever read:Aur kyaa is ke sivaa kijiye midhat us kiDo hilal ik jagah dekhe hain qudrat us ki.(What other praise can I lavish upon itTwo crescent moons were seen at one place – God be praised!)It’s only when you uncover these poetic gems that you realise what colonial occupation has done to suppress our literary heritage. These queer genres within Urdu poetry deserve a wider audience. Love – homosexual or otherwise, knows no bounds. Love is like that Greek quote – “What you didn’t do to bury me/But you forgot that I was a seed” – by the 20th century poet Dinos Christianopoulos, who was denounced by the literary community because of his (homo)sexual orientation. Sometimes, I like to think of love as a wildland fire on an empty landscape. A fire within fire, a hope within hope. It defies the topology of the region, the way poetry defies religious and social norms.Or as Ghalib would say, “Ishq par zor nahin, hai ye wo aatish Ghalib”!Salik heads the Social Media Communications (aka Ghalib-in-Chief) at Talk Journalism and he can be found tweeting about Poetry, Physics and Ghalib @baawraman

The ghazal originated in the Arabian peninsula during the 8th century, from where it spread to Persia, leading to the creation of the Persian ghazal. The modern Urdu ghazal is a love-child born out of cultural wedlock to a Persian father and an Indian mother. Its aesthetics are derived from Perso-Arabic Islamicate literature, including the gender of the proverbial ‘maashuq’ (beloved), which, in most cases, is grammatically gender neutral and the identity of the beloved could be either male or female. This is largely because of the Persian traditions which Urdu poetry inherited, as grammatically, in the Persian language, there is no clear distinction between male and female verbs or pronouns, and gender is impossible to determine from the construction of the sentence. Consider the following couplet by Ghalib:Yeh na thi hamari qismat ke visal-e yar hotaAgar aur jeete rahte yahi intizaar hota(It was not my fate to unite with the Beloved;Yet had I gone on living, I’d have kept up this same waiting)Now, in this couplet, even though the gender of the Beloved (yar) is grammatically masculine, it's gender neutral, yar, could mean either a female or a male.

The ghazal originated in the Arabian peninsula during the 8th century, from where it spread to Persia, leading to the creation of the Persian ghazal. The modern Urdu ghazal is a love-child born out of cultural wedlock to a Persian father and an Indian mother. Its aesthetics are derived from Perso-Arabic Islamicate literature, including the gender of the proverbial ‘maashuq’ (beloved), which, in most cases, is grammatically gender neutral and the identity of the beloved could be either male or female. This is largely because of the Persian traditions which Urdu poetry inherited, as grammatically, in the Persian language, there is no clear distinction between male and female verbs or pronouns, and gender is impossible to determine from the construction of the sentence. Consider the following couplet by Ghalib:Yeh na thi hamari qismat ke visal-e yar hotaAgar aur jeete rahte yahi intizaar hota(It was not my fate to unite with the Beloved;Yet had I gone on living, I’d have kept up this same waiting)Now, in this couplet, even though the gender of the Beloved (yar) is grammatically masculine, it's gender neutral, yar, could mean either a female or a male. Mir’s Beloved

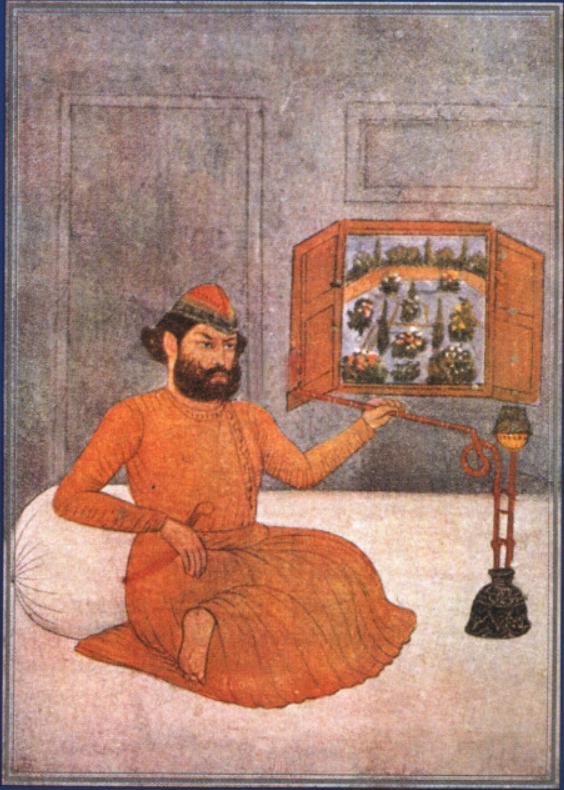

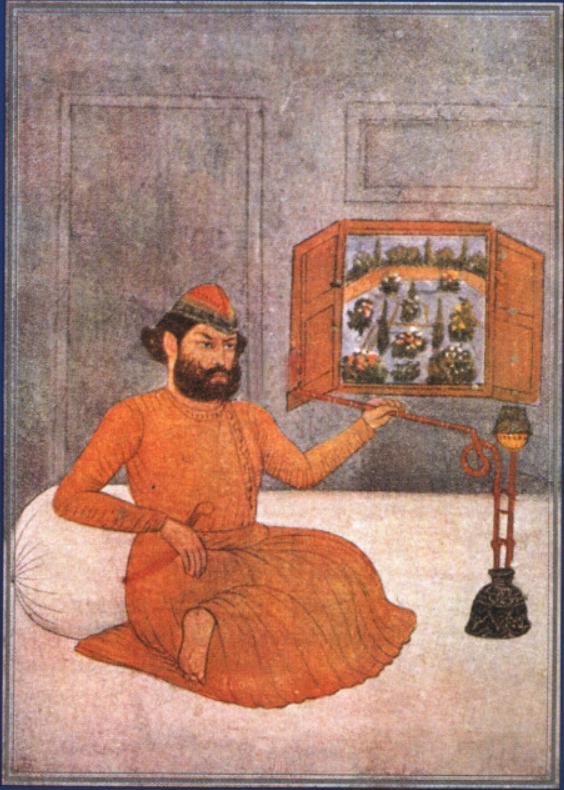

Great Urdu poets like Nasikh, Ghalib and Zauq, all looked upto their ‘ustaad’, Mir Muhammad Taqi 'Mir' (1722-1810), the ghazal poet who came to be known as ‘Khuda-e-Sukhan’ or the ‘God of Urdu Poetry’. Such is the stature of Mir that Ghalib (1797-1869) writes:‘Ghalib’, apana to aqeeda hai ba-qaul-e-‘Nasikh’aap be-bahara hain, jo mota’qid-e-Mir nahin.(Ghalib, it's my belief in the words of Nasikh.He who vows not on Mir is himself an ignoramus)Mir defied convention when it came to the representation of gender in his poems, which shaped the modern form of the Urdu ghazal. Mir’s fancying of an ‘attar ka launda’ – the son of a perfumer – and a ‘memar ka ladka’ – son of a mason – is quite evident in his poetry.Mir kya saade hain beemar hue jiske sababUsi attar ke laundey se dawaa lete hain(So innocent am I,I ask for medicine from the same perfumer’s boywho’s the cause of my disease!)A close analysis of Mir’s deewan (collection of poetry) reveals that his beloved is explicitly male, and he talks often about his fascination with adolescent boys, who just hit puberty. There are at least 225 such couplets which clearly refer to a male beloved, using terms like ‘ladka’, ‘launda’, ‘tifl’, ‘naunihal’, ‘pisar’.Consider the following couplets: Vay nahin to unhon ka bhai aurIshq karne ki kya manai hai(I want you, but if not you, just fine is your brother!I need to love, who the beloved is not the matter)Ladke birahmanon ke sandal bhari jabeenenHindostan mein dekhe so unse dil lagaye(Brahmin boys of India take away my heartBeautiful foreheads, headier with the fragrance of Sandal)Afsanakhwan ka ladka kya kahiye deedni haiQissa hamara uska yaaron shuneednin hai(The story-teller’s lad is a sight beyond compareAs is his and my story, a story beyond compare.)Woh baghbaan pisar kuch gul gulshagufta hai abYeh aur gul khila hai ek phoolon ki dukaan par(The florist has found a new flower –It is the gardener-boy, who has just flowered.)Kiya us aatishbaaz ke launde ka itna shauq MirBeh chali hai dekh kar usko tumhari raal kuch.(The fireworker’s son has fired my heart so,I can do nothing, but sit and salivate.) While not all Urdu poets wrote extensively on homosexual themes, there’s no dearth of poets with heterosexual identities who fancied young adolescent boys – though we don’t know if this desire translated into actual relationships. In the following couplet, Ghalib writes:Aamad-e-Khat se hua hay sard jo bazar-e-dostdood-e-shama-e-kushta tha shaid khat-e-rukhsar-e-dost(With the sprouting of the beard, demand for my beloved has diminished.Now it appears like the smoke of a dying fire.)(Today, we might view a relationship between an older man and a young boy far less benevolently but these poems belong to a time of rather different mores.) This tradition of love towards young boys dates back to early Islamic world of Arabia and Persia, where it was a common practice to have a young male lover. Important figures in the history of the ghazal, like the 8th century Persian poet Abu Nuwas and the 14th century Arab poet Nawaji Bin Hasan, also known as "Shams al-Din" or Sun Of Religion, wrote extensively on male homoerotic themes, where the beloved is a young boy who recently attained puberty. Homosexual love has always been a part of the ghazal’s history. But in India, it wasn’t until the late 19th century, when British Victorian mindsets around sexuality began to take root, that homosexual themes began to disappear from the Urdu ghazal. Barring the 20th century poets Firaaq Gorakhpuri (1896-1982) and Josh Malihabadi (1894-1982), whose homosexual relationships in their poetry and in their personal lives were widely known, there are hardly any examples from the recent past.However, although they are the most quoted and well-known, men who desire other men or boys don’t form the only kind of queer voice in the Urdu ghazal.

While not all Urdu poets wrote extensively on homosexual themes, there’s no dearth of poets with heterosexual identities who fancied young adolescent boys – though we don’t know if this desire translated into actual relationships. In the following couplet, Ghalib writes:Aamad-e-Khat se hua hay sard jo bazar-e-dostdood-e-shama-e-kushta tha shaid khat-e-rukhsar-e-dost(With the sprouting of the beard, demand for my beloved has diminished.Now it appears like the smoke of a dying fire.)(Today, we might view a relationship between an older man and a young boy far less benevolently but these poems belong to a time of rather different mores.) This tradition of love towards young boys dates back to early Islamic world of Arabia and Persia, where it was a common practice to have a young male lover. Important figures in the history of the ghazal, like the 8th century Persian poet Abu Nuwas and the 14th century Arab poet Nawaji Bin Hasan, also known as "Shams al-Din" or Sun Of Religion, wrote extensively on male homoerotic themes, where the beloved is a young boy who recently attained puberty. Homosexual love has always been a part of the ghazal’s history. But in India, it wasn’t until the late 19th century, when British Victorian mindsets around sexuality began to take root, that homosexual themes began to disappear from the Urdu ghazal. Barring the 20th century poets Firaaq Gorakhpuri (1896-1982) and Josh Malihabadi (1894-1982), whose homosexual relationships in their poetry and in their personal lives were widely known, there are hardly any examples from the recent past.However, although they are the most quoted and well-known, men who desire other men or boys don’t form the only kind of queer voice in the Urdu ghazal.Ghazals and the female voice

Urdu poetry has been the provenance of men, where the narrator and the beloved are referred to in a grammatically masculine gender. While this patriarchal convention creates a space for male homoeroticism, it completely negates and shuts the door on the idea of any female homoeroticism. The absence of female authorship in pre-modern Urdu poetry is a function of the Purdah system, which not only excluded women from the public sphere, but also from literature and the expression of ideas – homoerotic or otherwise. Enter Rekhti – an interesting genre of Urdu poetry which was developed in early 19th century Lucknow to counter the male “Rekhta” which was dominated by a male narrator and beloved. Rekhti is written in an exaggerated feminine voice by a male poet, highlighting social issues pertaining to women. In Rekhti, terms like ‘du-gana’, ‘ya-gana’, ‘zanakhi’, ‘begana’, ‘shakhi’, ‘ilachi’, ‘wari’, and ‘pyari’ loosely denote the female beloved. The term “Rekhti” was coined by Saadat Yaar Khan “Rangin” (1757-1835), noted for his sensitivity to gender issues. Rangin was also the first Urdu poet to compile a deewan about women titled “Angekhta” which translates to “The Aroused [Verses]”. The thematic contents of Rangin's “aroused” verses included adulterous sex between men and women, and sex between women and lustful women. But perhaps it’s important to remember that men impersonating the female voice didn’t make up for the absence of women. Author and literary critic Susanne Kappeler notes, “The assumption of the female point of view and narrative voice – the assumption of linguistic and narrative female ‘subjectivity’ – in no way lessens […] the fundamental elision of the woman as subject. On the contrary, it goes one step further in the total objectification of women.”As a genre, Rekhti is not exclusively homosexual – in fact, a common theme in Rekhti is the day-to-day conversations among courtesans in playful and naughty idioms. Rangin’s poetry, however, focussed more on sexual themes. Here’s a couplet that talks about a “taboo” topic, menstruation: Rangin qasam hai teri hi hun maile sir-se mainMat kholkar ke minnat-o-zaari izaar-band.(Rangin I swear to you I have my periodDo not keep pestering me to open the band of my trousers)Queer relationships and same-sex love are prohibited in Islam, but Rekhti poetry seems not to take heed, as seen in these lines by Rangin:Meri du-guna aur main yun nahin hain jaise Rekhta,Dono ki jane'n ek hain tane jo kasti ho abas.(My [female] lover and I are not scattered like [the] Urdu,Our two lives are one; you [female] taunt us for nothing.)Here’s another couplet of Rangin, in which he makes explicit reference to a dildo.Aaj kyun tu ne du-guna ye ‘saburaa’ bandhathes lagti hai, bhala kyunki bachchedani bache.(Why did you tie on this dildo, dear du-gunaIt hurts and pains, I fear for my womb.)There’s another sub-genre of Rekhti called Chaptinama, which is a kind of long poem dealing with lesbian erotic themes. Author Ruth Vanita describes Chapti as “play without a dildo”. Consider the following couplet of Qalandar Bakhsh Ju’rrat (1748-1809):“Aisi lazzat kahan hai mardon meinjaisi lazzat du-gana chapti mein.” (Where is the pleasure in men, compared to pleasure, du-guna, in Chapti.) Insha Allah Khan “Insha” (1756-1817), another prolific Rekhti poet, wrote extensively on lesbian love. Take the following verses, for example: Aag lene ko jo aayin to kahin laag lagaBibi hamsaai ne di jee men meri aag lagaNa bura mane to lun noch ko’ī muthi bharBegama har teri kyaari men hara sag laga(When she came to take fire, an attraction took hold;The neighbor lady lit a fire in my heartIf you don’t mind, may I seize a handful or two?Young lady, greens grow in every bed of yours!)Jan Sahib (1810-1886) wrote about sexual fantasies – not necessarily homo-erotic – with a playfull naughtiness: Le chuka munh me hai lallu meri sau bar zubaanho gaya kab ka musalmaan, ye kya kaafir hai.(He has sucked my tongue many a time, this lalluHe has long been a Muslim – he's no kafir.)Zaal to beshak hai tu, beta agar rustam nahinbhaar do do joru'on ka aur kamar me kham nahin.(You are certainly a Zaal, if not in fact a Rustam!You serve two wives, but your back isn't bent.)Another subgenre of Rekhti called ‘Saraapa’, which literally means ‘head to toe’, is one in which the poet writes about various parts of the body. Here’s Ju’rrat describing feet of his beloved:Aur jo hathon men utha lun to ajab lutf uthaaonPhir jo vo lutf uthana tujhe bitha ke dikhlaaon.(And if I lift the feet I would find a strange pleasureAnd then to make you sit and watch that pleasure-taking.)Or, this couplet where he talks about buttocks and thighs:Koh-e sureen dekho to sar phodo tumRanen makhmal si hain khvab-o-khurus chodo tum(And if you see the mountains of the derriere you would knock out your headAnd the thighs are like satin – make you leave all dreaming and thinking)

Insha Allah Khan “Insha” (1756-1817), another prolific Rekhti poet, wrote extensively on lesbian love. Take the following verses, for example: Aag lene ko jo aayin to kahin laag lagaBibi hamsaai ne di jee men meri aag lagaNa bura mane to lun noch ko’ī muthi bharBegama har teri kyaari men hara sag laga(When she came to take fire, an attraction took hold;The neighbor lady lit a fire in my heartIf you don’t mind, may I seize a handful or two?Young lady, greens grow in every bed of yours!)Jan Sahib (1810-1886) wrote about sexual fantasies – not necessarily homo-erotic – with a playfull naughtiness: Le chuka munh me hai lallu meri sau bar zubaanho gaya kab ka musalmaan, ye kya kaafir hai.(He has sucked my tongue many a time, this lalluHe has long been a Muslim – he's no kafir.)Zaal to beshak hai tu, beta agar rustam nahinbhaar do do joru'on ka aur kamar me kham nahin.(You are certainly a Zaal, if not in fact a Rustam!You serve two wives, but your back isn't bent.)Another subgenre of Rekhti called ‘Saraapa’, which literally means ‘head to toe’, is one in which the poet writes about various parts of the body. Here’s Ju’rrat describing feet of his beloved:Aur jo hathon men utha lun to ajab lutf uthaaonPhir jo vo lutf uthana tujhe bitha ke dikhlaaon.(And if I lift the feet I would find a strange pleasureAnd then to make you sit and watch that pleasure-taking.)Or, this couplet where he talks about buttocks and thighs:Koh-e sureen dekho to sar phodo tumRanen makhmal si hain khvab-o-khurus chodo tum(And if you see the mountains of the derriere you would knock out your headAnd the thighs are like satin – make you leave all dreaming and thinking) Here’s another example, and this is perhaps the most poetic description of a vagina I have ever read:Aur kyaa is ke sivaa kijiye midhat us kiDo hilal ik jagah dekhe hain qudrat us ki.(What other praise can I lavish upon itTwo crescent moons were seen at one place – God be praised!)It’s only when you uncover these poetic gems that you realise what colonial occupation has done to suppress our literary heritage. These queer genres within Urdu poetry deserve a wider audience. Love – homosexual or otherwise, knows no bounds. Love is like that Greek quote – “What you didn’t do to bury me/But you forgot that I was a seed” – by the 20th century poet Dinos Christianopoulos, who was denounced by the literary community because of his (homo)sexual orientation. Sometimes, I like to think of love as a wildland fire on an empty landscape. A fire within fire, a hope within hope. It defies the topology of the region, the way poetry defies religious and social norms.Or as Ghalib would say, “Ishq par zor nahin, hai ye wo aatish Ghalib”!Salik heads the Social Media Communications (aka Ghalib-in-Chief) at Talk Journalism and he can be found tweeting about Poetry, Physics and Ghalib @baawraman

Here’s another example, and this is perhaps the most poetic description of a vagina I have ever read:Aur kyaa is ke sivaa kijiye midhat us kiDo hilal ik jagah dekhe hain qudrat us ki.(What other praise can I lavish upon itTwo crescent moons were seen at one place – God be praised!)It’s only when you uncover these poetic gems that you realise what colonial occupation has done to suppress our literary heritage. These queer genres within Urdu poetry deserve a wider audience. Love – homosexual or otherwise, knows no bounds. Love is like that Greek quote – “What you didn’t do to bury me/But you forgot that I was a seed” – by the 20th century poet Dinos Christianopoulos, who was denounced by the literary community because of his (homo)sexual orientation. Sometimes, I like to think of love as a wildland fire on an empty landscape. A fire within fire, a hope within hope. It defies the topology of the region, the way poetry defies religious and social norms.Or as Ghalib would say, “Ishq par zor nahin, hai ye wo aatish Ghalib”!Salik heads the Social Media Communications (aka Ghalib-in-Chief) at Talk Journalism and he can be found tweeting about Poetry, Physics and Ghalib @baawraman