A self-styled Adonis recently told me that he has never really been attracted to Indian women (He’s Parsi. Don’t Ask. I Don’t Know.) Or short girls, but I’m just so beautiful that he feels especially drawn to me. That as a short Indian girl, I was somehow different from other short Indian girls -- an arbitration that he felt perfectly comfortable vocalizing as he was thinking through it, an articulation imbued with the knowledge that when a rich, handsome boy tells a girl that she’s pretty, she is going to listen.I laughed at that comment for hours. To what shall I compare this? Most accurately, I think I can compare this to the moment to a 21 year old girl with a twitter account dedicated to the Indian Minister of Road Transport and Highways waking up to a tweet from him telling her that he is going to inaugurate a toll-booth in Ghaziabad in her honor. When you are confronted with something this ridiculous, you begin to recognize the social forces and emotional anchors that undergird such interactions. You sometimes need things to get really weird before you can notice them. Flirting is about flair, and expression, but pay attention to most of the flirting you’re at the receiving end of and you can see what’s actually going on: exceptionalization.Are you even desirable as a heterosexual woman if men can’t describe you as an exception?When I was sixteen, a guy seven years older than me told me he liked me because I was smarter and more mature than women his age.My high school boyfriend told me that he liked me not only because I was “pretty, smart and funny” (teenage male thinking is remarkably complex), but because I was the ONLY girl he knew who was all three of those things. He was a top athlete in school, so you know, only the best girl was worthy of the boy. One of the more boring qualities of girlhood is that the desire you experience is predicated on the desire you produce. It was as if this male X-ray romantic vision was what discovered me, you know like the diamond in the rough that I was. Being the object of male desire/[male desire’s object?] was became a way for me to understand my own brilliance, because male biases are thought of as unassailable facts.This feeling of desirability was mapped onto otherwise competitive, jagged and antagonistic dynamics with the boys I went to school with. In class 9 I complained to my school counsellor that a boy in my class threw a razor blade at me and she said, “He comes from a conservative Brahmin family and isn’t used to a Muslim girl getting more marks than him -- also he probably thinks you’re pretty.” As I grew older, I realized that I couldn’t make the jokes about my body hair, or my father being a member of the Taliban (just joking yaar) go away, so I decided to be the best in whatever I could be the best in, which was many things. Boys thinking I am pretty felt like another victory, like I was queen bee of the wolfpack or something similarly muddled.

One of the more boring qualities of girlhood is that the desire you experience is predicated on the desire you produce. It was as if this male X-ray romantic vision was what discovered me, you know like the diamond in the rough that I was. Being the object of male desire/[male desire’s object?] was became a way for me to understand my own brilliance, because male biases are thought of as unassailable facts.This feeling of desirability was mapped onto otherwise competitive, jagged and antagonistic dynamics with the boys I went to school with. In class 9 I complained to my school counsellor that a boy in my class threw a razor blade at me and she said, “He comes from a conservative Brahmin family and isn’t used to a Muslim girl getting more marks than him -- also he probably thinks you’re pretty.” As I grew older, I realized that I couldn’t make the jokes about my body hair, or my father being a member of the Taliban (just joking yaar) go away, so I decided to be the best in whatever I could be the best in, which was many things. Boys thinking I am pretty felt like another victory, like I was queen bee of the wolfpack or something similarly muddled. This projected self-image operated through a fragile sense of my own girlhood; I believed that I had transcended the funda of being a girl -- because apparently something about me was too scary, too strange and I’ve always struggled with the idea that I was meant to be a girl or that I am much of a girl in the first place. I am an unremarkable combination of thin and fair, and when paired with my exotic Muslim name I often get turned into an object of fascination or some kind of conquest. I have always been cushioned in the idea that I possess a prettiness, which has filled me with this particular dread because it meant that I was palatable to men, and also this irritation that this “privilege” is something that they confer onto me.It is for this very reason that I find myself unable to internalize “your hotness is your own” as a self-love mantra. If it weren’t for the male-identified “privileges” of being a hot girl, then I would probably even forget that I had a body. The other thing, and this is a big one, is that I never really acted like how young pretty women are supposed to behave, and I don’t mean this in a cute way. Without getting into the specifics of all the harassment and bullying I have experienced, I realized very early on that that the thrill of being exceptionalized is followed by the violence and disposability of not being sanitized enough, of not being the kind of “good girl” men want to protect.

This projected self-image operated through a fragile sense of my own girlhood; I believed that I had transcended the funda of being a girl -- because apparently something about me was too scary, too strange and I’ve always struggled with the idea that I was meant to be a girl or that I am much of a girl in the first place. I am an unremarkable combination of thin and fair, and when paired with my exotic Muslim name I often get turned into an object of fascination or some kind of conquest. I have always been cushioned in the idea that I possess a prettiness, which has filled me with this particular dread because it meant that I was palatable to men, and also this irritation that this “privilege” is something that they confer onto me.It is for this very reason that I find myself unable to internalize “your hotness is your own” as a self-love mantra. If it weren’t for the male-identified “privileges” of being a hot girl, then I would probably even forget that I had a body. The other thing, and this is a big one, is that I never really acted like how young pretty women are supposed to behave, and I don’t mean this in a cute way. Without getting into the specifics of all the harassment and bullying I have experienced, I realized very early on that that the thrill of being exceptionalized is followed by the violence and disposability of not being sanitized enough, of not being the kind of “good girl” men want to protect. There came a point at which being cast as the modern-day trophy wife type of girlfriend filled me with an icky restlessness. The more powerful men thought I was, the more disposable I knew I had become, because the condition of my desirability was that I always had to be exactly what they wanted me to be, and nothing else. The initial point of the thrill for me was never that I was “not like other girls,” it was that I was better than the boys. But this was just me being stupid and hopeful, boys would never acknowledge this as fact, and the more threatened they feel the more cruel they become.It is hard to talk about myself in this way as a retrospective, packing years of my life into this terse linearity, so I can find a way to make the present easier to talk about. The easiest way I can describe these convoluted modes of recognition is through this quote from a Hannah Black interview, in which she is talking about an ex: “I must be a woman because you treat me how you treat women.”This is what it felt like, this acute powerlessness. While I can understand the feminine to be a source and expression of power, the truth is this is never how I experienced my girlhood. I began to feel the heartbreak of not being one of the boys, of not being hotter than the boys, of not being hot to the boys. This strange, shameful condition of being trapped between a “fuck you!” and a “pick me!” I find myself constantly reminding myself that I am not a bechaari, because even that is something men want. Or I tell myself that a 20 year old girl worried about not being pretty is one of the least important, most common things in the world, except assuming the voice of a mean old man against my feelings don’t make them go away.

There came a point at which being cast as the modern-day trophy wife type of girlfriend filled me with an icky restlessness. The more powerful men thought I was, the more disposable I knew I had become, because the condition of my desirability was that I always had to be exactly what they wanted me to be, and nothing else. The initial point of the thrill for me was never that I was “not like other girls,” it was that I was better than the boys. But this was just me being stupid and hopeful, boys would never acknowledge this as fact, and the more threatened they feel the more cruel they become.It is hard to talk about myself in this way as a retrospective, packing years of my life into this terse linearity, so I can find a way to make the present easier to talk about. The easiest way I can describe these convoluted modes of recognition is through this quote from a Hannah Black interview, in which she is talking about an ex: “I must be a woman because you treat me how you treat women.”This is what it felt like, this acute powerlessness. While I can understand the feminine to be a source and expression of power, the truth is this is never how I experienced my girlhood. I began to feel the heartbreak of not being one of the boys, of not being hotter than the boys, of not being hot to the boys. This strange, shameful condition of being trapped between a “fuck you!” and a “pick me!” I find myself constantly reminding myself that I am not a bechaari, because even that is something men want. Or I tell myself that a 20 year old girl worried about not being pretty is one of the least important, most common things in the world, except assuming the voice of a mean old man against my feelings don’t make them go away. The thing is: how do I have sex when I want to rupture everything men see as desirable about me -- because I know by now that this catalogue of desirable girl types only exist to make you feel as small as possible, to slot you so they don’t have to see you. How do I have sex when I don’t even see anything desirable about me - because realizing these things about how men see you can actually make you terrified of being seen at all.

The thing is: how do I have sex when I want to rupture everything men see as desirable about me -- because I know by now that this catalogue of desirable girl types only exist to make you feel as small as possible, to slot you so they don’t have to see you. How do I have sex when I don’t even see anything desirable about me - because realizing these things about how men see you can actually make you terrified of being seen at all. A few months ago, my friends were describing the rush of wanting to fuck people they see passing by: their types, the fantasy, the urgency, the lewdness of it. I remember having nothing to say, not because I was scandalized -- I just didn’t think anyone would reciprocate my desire to fuck. How do you even fantasize when you are unable to negotiate your own fuckability within yourself? How do you see other people as attractive when you don’t think of yourself as someone anyone would be attracted to? How do you see other people when you can barely see yourself?I was recently at a panel on “Technology and Erotics,” and the India head of a popular global online dating app said that Indians in their 20s have already dated more than people in their 40s. There is this narrative that us post-liberalization babies have access to greater vocabularies of desire and have more avenues to operationalize that desire. The pressure to be having sex as proof of our desirability is now compounded with this strange “jab main tumhari age ki thi toh TV peh ek he channel aata tha: Doordarshan” type of generational guilt. I remember laughing at what a perfect little sexless Indian girl I am hidden like that black and white channel at the end of the frenetically technicoloured dial.Being suspended in sexlessness when all of your friends are constantly in relationships, in-between relationships, and/or hooking up makes the holy trine of sex-positivity, body-positivity and self-love feel like a consolation prize. My attempts at rejecting prettiness resulted in me desexualizing myself. My desire to unravel the constituent parts of my desirability became a way for me to find different ways to tell myself that I am unattractive, and when you relate to yourself in this particular mode of of self-hatred you begin to see the different ways that social and personal interactions are structured to remind you of it. I would stand idly by as men I was talking to would ask out a friend, often wondering why I never measured up or received that kind of attention - there are numerous permutations of this exact feeling, stretched across different circumstances, but all amounting to the same thing: me being in a perennial state of feeling rejected. The paranoia of being thought of as ugly and unfuckable, the most unladylike feeling.

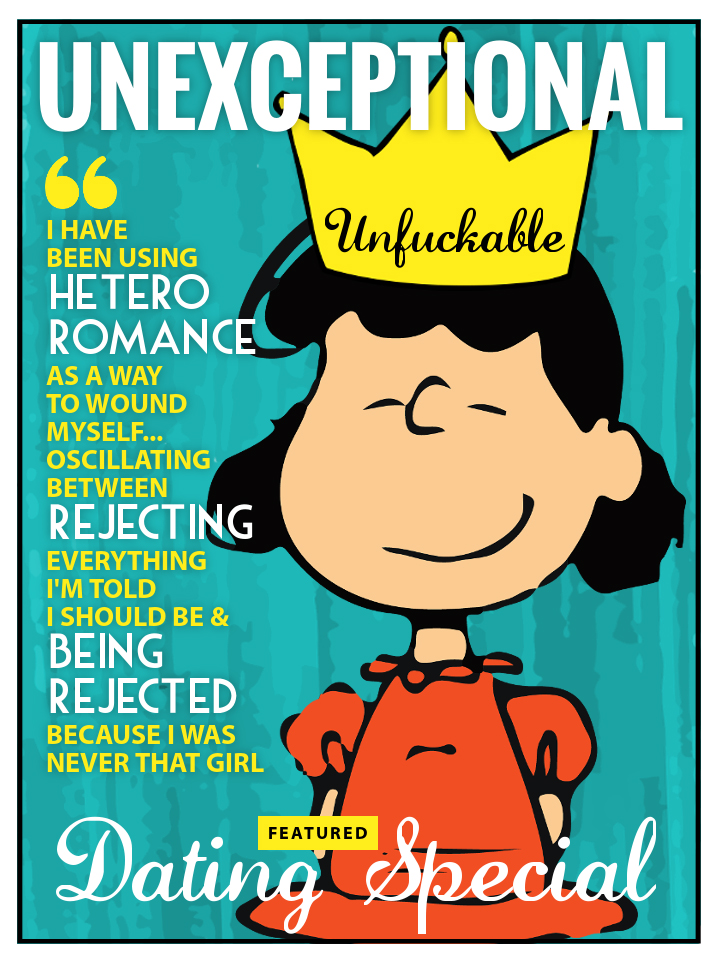

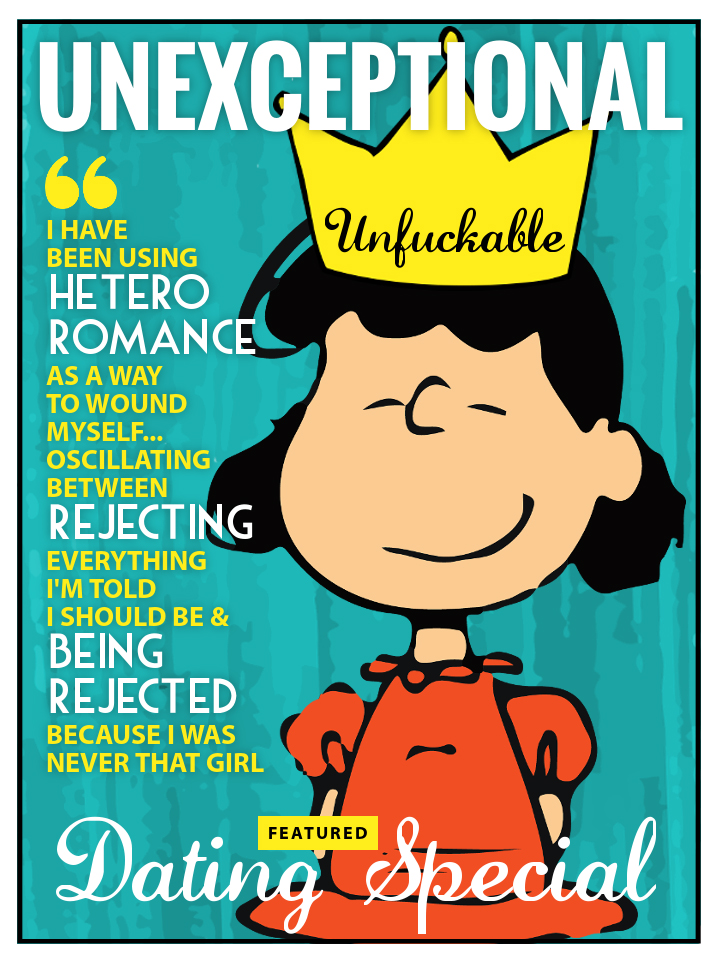

A few months ago, my friends were describing the rush of wanting to fuck people they see passing by: their types, the fantasy, the urgency, the lewdness of it. I remember having nothing to say, not because I was scandalized -- I just didn’t think anyone would reciprocate my desire to fuck. How do you even fantasize when you are unable to negotiate your own fuckability within yourself? How do you see other people as attractive when you don’t think of yourself as someone anyone would be attracted to? How do you see other people when you can barely see yourself?I was recently at a panel on “Technology and Erotics,” and the India head of a popular global online dating app said that Indians in their 20s have already dated more than people in their 40s. There is this narrative that us post-liberalization babies have access to greater vocabularies of desire and have more avenues to operationalize that desire. The pressure to be having sex as proof of our desirability is now compounded with this strange “jab main tumhari age ki thi toh TV peh ek he channel aata tha: Doordarshan” type of generational guilt. I remember laughing at what a perfect little sexless Indian girl I am hidden like that black and white channel at the end of the frenetically technicoloured dial.Being suspended in sexlessness when all of your friends are constantly in relationships, in-between relationships, and/or hooking up makes the holy trine of sex-positivity, body-positivity and self-love feel like a consolation prize. My attempts at rejecting prettiness resulted in me desexualizing myself. My desire to unravel the constituent parts of my desirability became a way for me to find different ways to tell myself that I am unattractive, and when you relate to yourself in this particular mode of of self-hatred you begin to see the different ways that social and personal interactions are structured to remind you of it. I would stand idly by as men I was talking to would ask out a friend, often wondering why I never measured up or received that kind of attention - there are numerous permutations of this exact feeling, stretched across different circumstances, but all amounting to the same thing: me being in a perennial state of feeling rejected. The paranoia of being thought of as ugly and unfuckable, the most unladylike feeling. I developed this fear of being seen and judged. I began to get used to panic attacks and crying uncontrollably in public, and every time I had to go outside I would have to spend hours emotionally training myself. On many days I would be too scared to even step out of my room to use the bathroom. I had already fallen in unreciprocated love with someone, a desire that embedded me in a circular relationship between hope, longing and rejection. The question of whether I am pretty or not drains, corrodes, and harms me so much that I would rather that we didn’t live in a world where these things mattered. I wish there was no such thing as prettiness, but this is an unrealistic hope, so yes I would rather be pretty than ugly, but don’t tell anyone I said that because we’re all beautiful, as you know.How to deal with the dilemma of hotness as a feminist? In a journey to be your own person/woman? Either you commit yourself to being ugly as a statement or you think of everything about you as attractive, also as a statement. Desiring in spite of feeling undesirable. Desiring in spite of feeling like your ugliest, most unfuckable self. If there’s one thing I have learned, it is to listen to what my paranoias and fantasies are trying to tell me. Who do I tell myself I have to be in order for me to stop punishing myself? Whose pleasure, whose power? I have been using hetero-romance as a way to wound myself, oscillating between wanting to reject the everything I have been told I should be and feeling rejected because I know I never was “that girl” anyway.I found some brief respite in the image of the exceptional girl, but then there is also the violence and the heartbreak and the anxiety of what will happen if it is revealed that I am not exceptional. I would like to derive no pleasure at all from how men see me, because then I can get rid of the pain of not being a man. But it is hard to speak about detachments when there isn’t exactly anything else you can attach yourself to.

I developed this fear of being seen and judged. I began to get used to panic attacks and crying uncontrollably in public, and every time I had to go outside I would have to spend hours emotionally training myself. On many days I would be too scared to even step out of my room to use the bathroom. I had already fallen in unreciprocated love with someone, a desire that embedded me in a circular relationship between hope, longing and rejection. The question of whether I am pretty or not drains, corrodes, and harms me so much that I would rather that we didn’t live in a world where these things mattered. I wish there was no such thing as prettiness, but this is an unrealistic hope, so yes I would rather be pretty than ugly, but don’t tell anyone I said that because we’re all beautiful, as you know.How to deal with the dilemma of hotness as a feminist? In a journey to be your own person/woman? Either you commit yourself to being ugly as a statement or you think of everything about you as attractive, also as a statement. Desiring in spite of feeling undesirable. Desiring in spite of feeling like your ugliest, most unfuckable self. If there’s one thing I have learned, it is to listen to what my paranoias and fantasies are trying to tell me. Who do I tell myself I have to be in order for me to stop punishing myself? Whose pleasure, whose power? I have been using hetero-romance as a way to wound myself, oscillating between wanting to reject the everything I have been told I should be and feeling rejected because I know I never was “that girl” anyway.I found some brief respite in the image of the exceptional girl, but then there is also the violence and the heartbreak and the anxiety of what will happen if it is revealed that I am not exceptional. I would like to derive no pleasure at all from how men see me, because then I can get rid of the pain of not being a man. But it is hard to speak about detachments when there isn’t exactly anything else you can attach yourself to. Then there is the complexity of what I actually fantasize about, which is, being loved in spite of heterosexuality and patriarchy. I want to exist outside the realm of dating, outside this thing of being judged for having a face and a body, outside of these ritualized prevarications.I don’t care how much sex you have and how soon - often critiques of dating turn into these moralistic ventures and like, I’m a chill and cool girl I promise. I just want to figure out what desirability means and why I feel me being who I am renders me unfuckable. Perhaps most importantly, I have learned to not let rejection turn me into some stereotype of male dejection, to wrench it away from narratives of entitlement and abuse. Rejection is physically overpowering. The days you feel it you are completely engulfed, and packed within is an urgency that needs direction. I was both terrified that I told a boy that I had feelings for him that I was willing to commit to (ugh, but like, not a marriage) and that in the absence of the kind of reciprocation I fantasized about, I was turning a figure of obsessive insecurity, that I was not respecting his boundaries. There exists a space to mediate all of this that is not retributive - you don’t want to punish yourself or the other person.I keep holding on to this kind of grace, which I think helps me, but I also wonder how anger can be restorative. So on some days I try to be angry, half-apologetic. I don’t have the answers because I am figuring out the script for myself, and this in itself is a feminist triumph. I want to believe, I think I do, that it will guide us towards loving ourselves with as much care and generosity, as in our fantasies we practice loving someone else.

Then there is the complexity of what I actually fantasize about, which is, being loved in spite of heterosexuality and patriarchy. I want to exist outside the realm of dating, outside this thing of being judged for having a face and a body, outside of these ritualized prevarications.I don’t care how much sex you have and how soon - often critiques of dating turn into these moralistic ventures and like, I’m a chill and cool girl I promise. I just want to figure out what desirability means and why I feel me being who I am renders me unfuckable. Perhaps most importantly, I have learned to not let rejection turn me into some stereotype of male dejection, to wrench it away from narratives of entitlement and abuse. Rejection is physically overpowering. The days you feel it you are completely engulfed, and packed within is an urgency that needs direction. I was both terrified that I told a boy that I had feelings for him that I was willing to commit to (ugh, but like, not a marriage) and that in the absence of the kind of reciprocation I fantasized about, I was turning a figure of obsessive insecurity, that I was not respecting his boundaries. There exists a space to mediate all of this that is not retributive - you don’t want to punish yourself or the other person.I keep holding on to this kind of grace, which I think helps me, but I also wonder how anger can be restorative. So on some days I try to be angry, half-apologetic. I don’t have the answers because I am figuring out the script for myself, and this in itself is a feminist triumph. I want to believe, I think I do, that it will guide us towards loving ourselves with as much care and generosity, as in our fantasies we practice loving someone else.

One of the more boring qualities of girlhood is that the desire you experience is predicated on the desire you produce. It was as if this male X-ray romantic vision was what discovered me, you know like the diamond in the rough that I was. Being the object of male desire/[male desire’s object?] was became a way for me to understand my own brilliance, because male biases are thought of as unassailable facts.This feeling of desirability was mapped onto otherwise competitive, jagged and antagonistic dynamics with the boys I went to school with. In class 9 I complained to my school counsellor that a boy in my class threw a razor blade at me and she said, “He comes from a conservative Brahmin family and isn’t used to a Muslim girl getting more marks than him -- also he probably thinks you’re pretty.” As I grew older, I realized that I couldn’t make the jokes about my body hair, or my father being a member of the Taliban (just joking yaar) go away, so I decided to be the best in whatever I could be the best in, which was many things. Boys thinking I am pretty felt like another victory, like I was queen bee of the wolfpack or something similarly muddled.

One of the more boring qualities of girlhood is that the desire you experience is predicated on the desire you produce. It was as if this male X-ray romantic vision was what discovered me, you know like the diamond in the rough that I was. Being the object of male desire/[male desire’s object?] was became a way for me to understand my own brilliance, because male biases are thought of as unassailable facts.This feeling of desirability was mapped onto otherwise competitive, jagged and antagonistic dynamics with the boys I went to school with. In class 9 I complained to my school counsellor that a boy in my class threw a razor blade at me and she said, “He comes from a conservative Brahmin family and isn’t used to a Muslim girl getting more marks than him -- also he probably thinks you’re pretty.” As I grew older, I realized that I couldn’t make the jokes about my body hair, or my father being a member of the Taliban (just joking yaar) go away, so I decided to be the best in whatever I could be the best in, which was many things. Boys thinking I am pretty felt like another victory, like I was queen bee of the wolfpack or something similarly muddled. This projected self-image operated through a fragile sense of my own girlhood; I believed that I had transcended the funda of being a girl -- because apparently something about me was too scary, too strange and I’ve always struggled with the idea that I was meant to be a girl or that I am much of a girl in the first place. I am an unremarkable combination of thin and fair, and when paired with my exotic Muslim name I often get turned into an object of fascination or some kind of conquest. I have always been cushioned in the idea that I possess a prettiness, which has filled me with this particular dread because it meant that I was palatable to men, and also this irritation that this “privilege” is something that they confer onto me.It is for this very reason that I find myself unable to internalize “your hotness is your own” as a self-love mantra. If it weren’t for the male-identified “privileges” of being a hot girl, then I would probably even forget that I had a body. The other thing, and this is a big one, is that I never really acted like how young pretty women are supposed to behave, and I don’t mean this in a cute way. Without getting into the specifics of all the harassment and bullying I have experienced, I realized very early on that that the thrill of being exceptionalized is followed by the violence and disposability of not being sanitized enough, of not being the kind of “good girl” men want to protect.

This projected self-image operated through a fragile sense of my own girlhood; I believed that I had transcended the funda of being a girl -- because apparently something about me was too scary, too strange and I’ve always struggled with the idea that I was meant to be a girl or that I am much of a girl in the first place. I am an unremarkable combination of thin and fair, and when paired with my exotic Muslim name I often get turned into an object of fascination or some kind of conquest. I have always been cushioned in the idea that I possess a prettiness, which has filled me with this particular dread because it meant that I was palatable to men, and also this irritation that this “privilege” is something that they confer onto me.It is for this very reason that I find myself unable to internalize “your hotness is your own” as a self-love mantra. If it weren’t for the male-identified “privileges” of being a hot girl, then I would probably even forget that I had a body. The other thing, and this is a big one, is that I never really acted like how young pretty women are supposed to behave, and I don’t mean this in a cute way. Without getting into the specifics of all the harassment and bullying I have experienced, I realized very early on that that the thrill of being exceptionalized is followed by the violence and disposability of not being sanitized enough, of not being the kind of “good girl” men want to protect. There came a point at which being cast as the modern-day trophy wife type of girlfriend filled me with an icky restlessness. The more powerful men thought I was, the more disposable I knew I had become, because the condition of my desirability was that I always had to be exactly what they wanted me to be, and nothing else. The initial point of the thrill for me was never that I was “not like other girls,” it was that I was better than the boys. But this was just me being stupid and hopeful, boys would never acknowledge this as fact, and the more threatened they feel the more cruel they become.It is hard to talk about myself in this way as a retrospective, packing years of my life into this terse linearity, so I can find a way to make the present easier to talk about. The easiest way I can describe these convoluted modes of recognition is through this quote from a Hannah Black interview, in which she is talking about an ex: “I must be a woman because you treat me how you treat women.”This is what it felt like, this acute powerlessness. While I can understand the feminine to be a source and expression of power, the truth is this is never how I experienced my girlhood. I began to feel the heartbreak of not being one of the boys, of not being hotter than the boys, of not being hot to the boys. This strange, shameful condition of being trapped between a “fuck you!” and a “pick me!” I find myself constantly reminding myself that I am not a bechaari, because even that is something men want. Or I tell myself that a 20 year old girl worried about not being pretty is one of the least important, most common things in the world, except assuming the voice of a mean old man against my feelings don’t make them go away.

There came a point at which being cast as the modern-day trophy wife type of girlfriend filled me with an icky restlessness. The more powerful men thought I was, the more disposable I knew I had become, because the condition of my desirability was that I always had to be exactly what they wanted me to be, and nothing else. The initial point of the thrill for me was never that I was “not like other girls,” it was that I was better than the boys. But this was just me being stupid and hopeful, boys would never acknowledge this as fact, and the more threatened they feel the more cruel they become.It is hard to talk about myself in this way as a retrospective, packing years of my life into this terse linearity, so I can find a way to make the present easier to talk about. The easiest way I can describe these convoluted modes of recognition is through this quote from a Hannah Black interview, in which she is talking about an ex: “I must be a woman because you treat me how you treat women.”This is what it felt like, this acute powerlessness. While I can understand the feminine to be a source and expression of power, the truth is this is never how I experienced my girlhood. I began to feel the heartbreak of not being one of the boys, of not being hotter than the boys, of not being hot to the boys. This strange, shameful condition of being trapped between a “fuck you!” and a “pick me!” I find myself constantly reminding myself that I am not a bechaari, because even that is something men want. Or I tell myself that a 20 year old girl worried about not being pretty is one of the least important, most common things in the world, except assuming the voice of a mean old man against my feelings don’t make them go away. The thing is: how do I have sex when I want to rupture everything men see as desirable about me -- because I know by now that this catalogue of desirable girl types only exist to make you feel as small as possible, to slot you so they don’t have to see you. How do I have sex when I don’t even see anything desirable about me - because realizing these things about how men see you can actually make you terrified of being seen at all.

The thing is: how do I have sex when I want to rupture everything men see as desirable about me -- because I know by now that this catalogue of desirable girl types only exist to make you feel as small as possible, to slot you so they don’t have to see you. How do I have sex when I don’t even see anything desirable about me - because realizing these things about how men see you can actually make you terrified of being seen at all. A few months ago, my friends were describing the rush of wanting to fuck people they see passing by: their types, the fantasy, the urgency, the lewdness of it. I remember having nothing to say, not because I was scandalized -- I just didn’t think anyone would reciprocate my desire to fuck. How do you even fantasize when you are unable to negotiate your own fuckability within yourself? How do you see other people as attractive when you don’t think of yourself as someone anyone would be attracted to? How do you see other people when you can barely see yourself?I was recently at a panel on “Technology and Erotics,” and the India head of a popular global online dating app said that Indians in their 20s have already dated more than people in their 40s. There is this narrative that us post-liberalization babies have access to greater vocabularies of desire and have more avenues to operationalize that desire. The pressure to be having sex as proof of our desirability is now compounded with this strange “jab main tumhari age ki thi toh TV peh ek he channel aata tha: Doordarshan” type of generational guilt. I remember laughing at what a perfect little sexless Indian girl I am hidden like that black and white channel at the end of the frenetically technicoloured dial.Being suspended in sexlessness when all of your friends are constantly in relationships, in-between relationships, and/or hooking up makes the holy trine of sex-positivity, body-positivity and self-love feel like a consolation prize. My attempts at rejecting prettiness resulted in me desexualizing myself. My desire to unravel the constituent parts of my desirability became a way for me to find different ways to tell myself that I am unattractive, and when you relate to yourself in this particular mode of of self-hatred you begin to see the different ways that social and personal interactions are structured to remind you of it. I would stand idly by as men I was talking to would ask out a friend, often wondering why I never measured up or received that kind of attention - there are numerous permutations of this exact feeling, stretched across different circumstances, but all amounting to the same thing: me being in a perennial state of feeling rejected. The paranoia of being thought of as ugly and unfuckable, the most unladylike feeling.

A few months ago, my friends were describing the rush of wanting to fuck people they see passing by: their types, the fantasy, the urgency, the lewdness of it. I remember having nothing to say, not because I was scandalized -- I just didn’t think anyone would reciprocate my desire to fuck. How do you even fantasize when you are unable to negotiate your own fuckability within yourself? How do you see other people as attractive when you don’t think of yourself as someone anyone would be attracted to? How do you see other people when you can barely see yourself?I was recently at a panel on “Technology and Erotics,” and the India head of a popular global online dating app said that Indians in their 20s have already dated more than people in their 40s. There is this narrative that us post-liberalization babies have access to greater vocabularies of desire and have more avenues to operationalize that desire. The pressure to be having sex as proof of our desirability is now compounded with this strange “jab main tumhari age ki thi toh TV peh ek he channel aata tha: Doordarshan” type of generational guilt. I remember laughing at what a perfect little sexless Indian girl I am hidden like that black and white channel at the end of the frenetically technicoloured dial.Being suspended in sexlessness when all of your friends are constantly in relationships, in-between relationships, and/or hooking up makes the holy trine of sex-positivity, body-positivity and self-love feel like a consolation prize. My attempts at rejecting prettiness resulted in me desexualizing myself. My desire to unravel the constituent parts of my desirability became a way for me to find different ways to tell myself that I am unattractive, and when you relate to yourself in this particular mode of of self-hatred you begin to see the different ways that social and personal interactions are structured to remind you of it. I would stand idly by as men I was talking to would ask out a friend, often wondering why I never measured up or received that kind of attention - there are numerous permutations of this exact feeling, stretched across different circumstances, but all amounting to the same thing: me being in a perennial state of feeling rejected. The paranoia of being thought of as ugly and unfuckable, the most unladylike feeling. I developed this fear of being seen and judged. I began to get used to panic attacks and crying uncontrollably in public, and every time I had to go outside I would have to spend hours emotionally training myself. On many days I would be too scared to even step out of my room to use the bathroom. I had already fallen in unreciprocated love with someone, a desire that embedded me in a circular relationship between hope, longing and rejection. The question of whether I am pretty or not drains, corrodes, and harms me so much that I would rather that we didn’t live in a world where these things mattered. I wish there was no such thing as prettiness, but this is an unrealistic hope, so yes I would rather be pretty than ugly, but don’t tell anyone I said that because we’re all beautiful, as you know.How to deal with the dilemma of hotness as a feminist? In a journey to be your own person/woman? Either you commit yourself to being ugly as a statement or you think of everything about you as attractive, also as a statement. Desiring in spite of feeling undesirable. Desiring in spite of feeling like your ugliest, most unfuckable self. If there’s one thing I have learned, it is to listen to what my paranoias and fantasies are trying to tell me. Who do I tell myself I have to be in order for me to stop punishing myself? Whose pleasure, whose power? I have been using hetero-romance as a way to wound myself, oscillating between wanting to reject the everything I have been told I should be and feeling rejected because I know I never was “that girl” anyway.I found some brief respite in the image of the exceptional girl, but then there is also the violence and the heartbreak and the anxiety of what will happen if it is revealed that I am not exceptional. I would like to derive no pleasure at all from how men see me, because then I can get rid of the pain of not being a man. But it is hard to speak about detachments when there isn’t exactly anything else you can attach yourself to.

I developed this fear of being seen and judged. I began to get used to panic attacks and crying uncontrollably in public, and every time I had to go outside I would have to spend hours emotionally training myself. On many days I would be too scared to even step out of my room to use the bathroom. I had already fallen in unreciprocated love with someone, a desire that embedded me in a circular relationship between hope, longing and rejection. The question of whether I am pretty or not drains, corrodes, and harms me so much that I would rather that we didn’t live in a world where these things mattered. I wish there was no such thing as prettiness, but this is an unrealistic hope, so yes I would rather be pretty than ugly, but don’t tell anyone I said that because we’re all beautiful, as you know.How to deal with the dilemma of hotness as a feminist? In a journey to be your own person/woman? Either you commit yourself to being ugly as a statement or you think of everything about you as attractive, also as a statement. Desiring in spite of feeling undesirable. Desiring in spite of feeling like your ugliest, most unfuckable self. If there’s one thing I have learned, it is to listen to what my paranoias and fantasies are trying to tell me. Who do I tell myself I have to be in order for me to stop punishing myself? Whose pleasure, whose power? I have been using hetero-romance as a way to wound myself, oscillating between wanting to reject the everything I have been told I should be and feeling rejected because I know I never was “that girl” anyway.I found some brief respite in the image of the exceptional girl, but then there is also the violence and the heartbreak and the anxiety of what will happen if it is revealed that I am not exceptional. I would like to derive no pleasure at all from how men see me, because then I can get rid of the pain of not being a man. But it is hard to speak about detachments when there isn’t exactly anything else you can attach yourself to. Then there is the complexity of what I actually fantasize about, which is, being loved in spite of heterosexuality and patriarchy. I want to exist outside the realm of dating, outside this thing of being judged for having a face and a body, outside of these ritualized prevarications.I don’t care how much sex you have and how soon - often critiques of dating turn into these moralistic ventures and like, I’m a chill and cool girl I promise. I just want to figure out what desirability means and why I feel me being who I am renders me unfuckable. Perhaps most importantly, I have learned to not let rejection turn me into some stereotype of male dejection, to wrench it away from narratives of entitlement and abuse. Rejection is physically overpowering. The days you feel it you are completely engulfed, and packed within is an urgency that needs direction. I was both terrified that I told a boy that I had feelings for him that I was willing to commit to (ugh, but like, not a marriage) and that in the absence of the kind of reciprocation I fantasized about, I was turning a figure of obsessive insecurity, that I was not respecting his boundaries. There exists a space to mediate all of this that is not retributive - you don’t want to punish yourself or the other person.I keep holding on to this kind of grace, which I think helps me, but I also wonder how anger can be restorative. So on some days I try to be angry, half-apologetic. I don’t have the answers because I am figuring out the script for myself, and this in itself is a feminist triumph. I want to believe, I think I do, that it will guide us towards loving ourselves with as much care and generosity, as in our fantasies we practice loving someone else.

Then there is the complexity of what I actually fantasize about, which is, being loved in spite of heterosexuality and patriarchy. I want to exist outside the realm of dating, outside this thing of being judged for having a face and a body, outside of these ritualized prevarications.I don’t care how much sex you have and how soon - often critiques of dating turn into these moralistic ventures and like, I’m a chill and cool girl I promise. I just want to figure out what desirability means and why I feel me being who I am renders me unfuckable. Perhaps most importantly, I have learned to not let rejection turn me into some stereotype of male dejection, to wrench it away from narratives of entitlement and abuse. Rejection is physically overpowering. The days you feel it you are completely engulfed, and packed within is an urgency that needs direction. I was both terrified that I told a boy that I had feelings for him that I was willing to commit to (ugh, but like, not a marriage) and that in the absence of the kind of reciprocation I fantasized about, I was turning a figure of obsessive insecurity, that I was not respecting his boundaries. There exists a space to mediate all of this that is not retributive - you don’t want to punish yourself or the other person.I keep holding on to this kind of grace, which I think helps me, but I also wonder how anger can be restorative. So on some days I try to be angry, half-apologetic. I don’t have the answers because I am figuring out the script for myself, and this in itself is a feminist triumph. I want to believe, I think I do, that it will guide us towards loving ourselves with as much care and generosity, as in our fantasies we practice loving someone else.