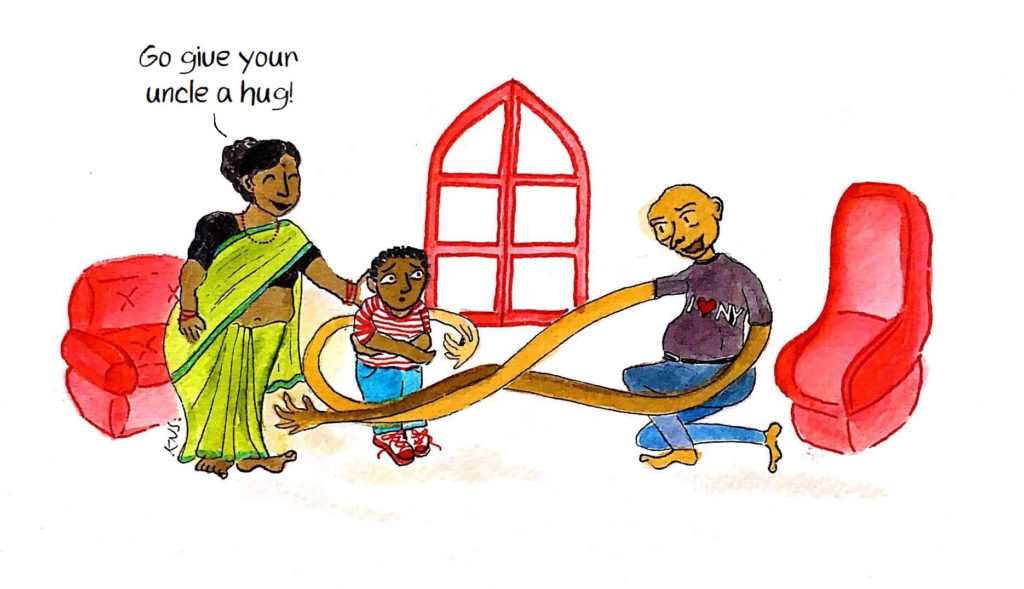

A sexuality educator wonders if focusing all our energy only on preventing abuse, instead of building autonomy, is missing the woods for the trees. By Srinidhi RaghavanIllustrated by Kruthika NS @theworkplacedoodlerI was having a conversation with my seven-year-old niece a few months ago when she told me that her school had introduced “good touch” and “bad touch” to her. As someone who talks about touch, sex, romance, consent on a regular basis, I asked her what she learnt. I was not surprised by her response: she summarised that all touching of her private parts was bad and all touching by “certain” members of the family/outsiders was bad. She told me that the examples given by her (well-meaning) teacher involved male figures harassing and preying on young girls. This teaching had resulted in her telling her grandfather not to touch her feet or her grandmother not to wash her during a bath.I remember asking my niece, “If I touch you, what does it make you feel?” She didn’t know what to answer. Even today, after several open discussions with her on touch and consent, I see her struggle with this, including with the idea of “strangers touching her” (which she’d been taught was bad) vs “known persons touching her” (which she’d been taught was okay).It’s understandable that teachers – and parents – would want kids to learn about different kinds of touch in order to help keep them safe. But I can’t help wonder if this “good touch” and “bad touch” business needs some rethinking.

By Srinidhi RaghavanIllustrated by Kruthika NS @theworkplacedoodlerI was having a conversation with my seven-year-old niece a few months ago when she told me that her school had introduced “good touch” and “bad touch” to her. As someone who talks about touch, sex, romance, consent on a regular basis, I asked her what she learnt. I was not surprised by her response: she summarised that all touching of her private parts was bad and all touching by “certain” members of the family/outsiders was bad. She told me that the examples given by her (well-meaning) teacher involved male figures harassing and preying on young girls. This teaching had resulted in her telling her grandfather not to touch her feet or her grandmother not to wash her during a bath.I remember asking my niece, “If I touch you, what does it make you feel?” She didn’t know what to answer. Even today, after several open discussions with her on touch and consent, I see her struggle with this, including with the idea of “strangers touching her” (which she’d been taught was bad) vs “known persons touching her” (which she’d been taught was okay).It’s understandable that teachers – and parents – would want kids to learn about different kinds of touch in order to help keep them safe. But I can’t help wonder if this “good touch” and “bad touch” business needs some rethinking. My niece’s confusion transports me back by six years to the first time I did a session on preventing child sexual abuse. I had said the same stuff about “good” and “bad” touch (it was an easy trap to fall into then, as it is now, especially since so much of the material we are provided around child sexual abuse uses this terminology). A short while after I finished the session and was packing my bag, a little girl, around 10 years old, walked up to me. She wanted to ask me what I meant by bad touch and how she was supposed to know it – the confusion on her face was remarkable. I myself was at a loss to respond helpfully, and I don’t think I provided her with a satisfactory answer.Years later, I still struggle to explain why I am uncomfortable with this terminology, but let me try.First, what is “good” touch? What is “bad”? How is a child supposed to determine this, and how do we teach them this without being broad and prescriptive in our explanation? One of my own fears about the way we advocate for good and bad touch is that the child may begin associating the touching of “private” parts with “bad”, and – therefore, all touching – with abuse. This association, even if made loosely, has confused many kids who I have worked with or spoken to.Second, considering that the perpetrators of abuse are often known to the victim, teaching kids this “known” vs “unknown” person dichotomy is pretty useless.Third, it is hard to assess how a child, any child, would respond to touch that is unwelcome. If it comes from a known person or is followed by a lot of grooming (that is, creating a bond and gaining a child’s trust in order to sexually abuse them), the child may not be in a place to identify the touch as “bad”. The experience of abuse itself sometimes makes it hard to not internalise shame – classifying it as “bad” only adds more guilt and shame into the mix, because a person may have experienced pleasure in a ‘wrong’ touch, which painfully complicates their sexual and psychological universe.To me, it sounds like a moral judgement is being made when we say good and bad touch – the language has a strong sense of what is supposed to be pleasurable and what is not, what is violent and what is not, and moral frameworks are not usually very helpful. Is all sexual touch bad? If it is bad, are we supposed to never get pleasure from it? Are we supposed to automatically feel discomfort if we are touched by a stranger, even if the touch is not sexual? How does this shape an overall perspective on sex?What then do we do when a 16-year-old child encounters touching of the private parts and feels pleasure? Are we to determine by our standards that it is harassment because they are 16 – since the law says so? Or is it not harassment because the child felt pleasure? The answers are not easy – in fact they are context dependent, but we don’t talk about these things enough, in a world where we also don’t talk about sex enough.

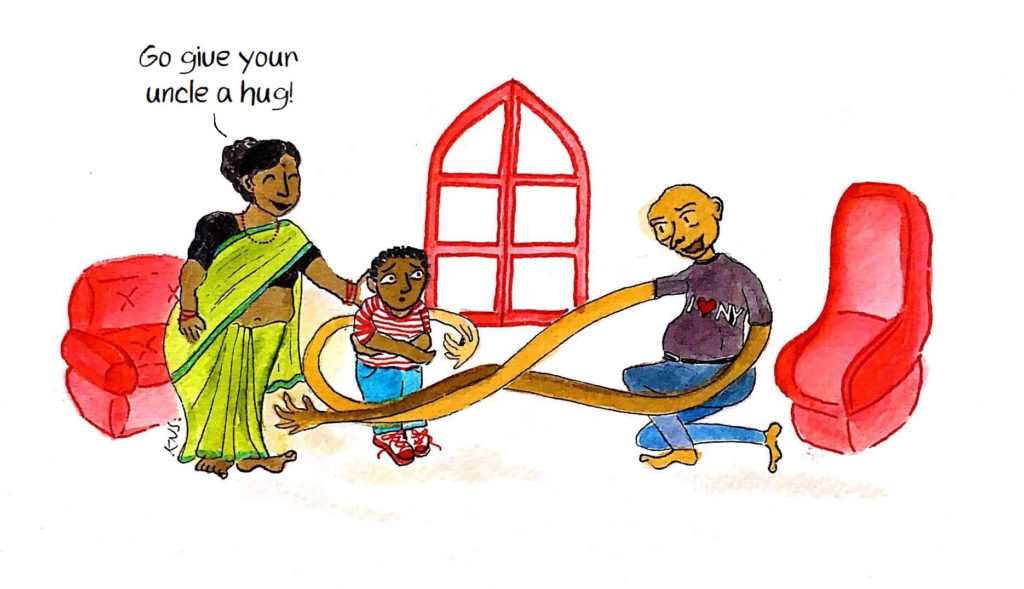

My niece’s confusion transports me back by six years to the first time I did a session on preventing child sexual abuse. I had said the same stuff about “good” and “bad” touch (it was an easy trap to fall into then, as it is now, especially since so much of the material we are provided around child sexual abuse uses this terminology). A short while after I finished the session and was packing my bag, a little girl, around 10 years old, walked up to me. She wanted to ask me what I meant by bad touch and how she was supposed to know it – the confusion on her face was remarkable. I myself was at a loss to respond helpfully, and I don’t think I provided her with a satisfactory answer.Years later, I still struggle to explain why I am uncomfortable with this terminology, but let me try.First, what is “good” touch? What is “bad”? How is a child supposed to determine this, and how do we teach them this without being broad and prescriptive in our explanation? One of my own fears about the way we advocate for good and bad touch is that the child may begin associating the touching of “private” parts with “bad”, and – therefore, all touching – with abuse. This association, even if made loosely, has confused many kids who I have worked with or spoken to.Second, considering that the perpetrators of abuse are often known to the victim, teaching kids this “known” vs “unknown” person dichotomy is pretty useless.Third, it is hard to assess how a child, any child, would respond to touch that is unwelcome. If it comes from a known person or is followed by a lot of grooming (that is, creating a bond and gaining a child’s trust in order to sexually abuse them), the child may not be in a place to identify the touch as “bad”. The experience of abuse itself sometimes makes it hard to not internalise shame – classifying it as “bad” only adds more guilt and shame into the mix, because a person may have experienced pleasure in a ‘wrong’ touch, which painfully complicates their sexual and psychological universe.To me, it sounds like a moral judgement is being made when we say good and bad touch – the language has a strong sense of what is supposed to be pleasurable and what is not, what is violent and what is not, and moral frameworks are not usually very helpful. Is all sexual touch bad? If it is bad, are we supposed to never get pleasure from it? Are we supposed to automatically feel discomfort if we are touched by a stranger, even if the touch is not sexual? How does this shape an overall perspective on sex?What then do we do when a 16-year-old child encounters touching of the private parts and feels pleasure? Are we to determine by our standards that it is harassment because they are 16 – since the law says so? Or is it not harassment because the child felt pleasure? The answers are not easy – in fact they are context dependent, but we don’t talk about these things enough, in a world where we also don’t talk about sex enough. And so, for instance, how does this intersect with kinds of touch that society does not consider acceptable? Take masturbation, for example. This form of touch could be pleasurable for the adolescent learning to explore their body, but is often regarded as taboo and made out to be a kind of bad touch too. When sexual pleasure is almost never spoken of, and sexual touch is overwhelmingly tied up with shame, we need to think about how helpful it really is in this context to use the terms good touch and bad touch. Do we then end up doing more harm than good in the long run? Is good touch and bad touch, to put it simply, an incomplete education? Taught in a vacuum – in the absence of any comprehensive sexuality education, what does it really leave the child with?Back in 2009, Tulir, an organisation working to prevent child sexual abuse, began advocating for a shift in the language we use to discuss touch and abuse with children. They prefer the terms “safe touch”, “unsafe touch” and “confusing touch” as an opening for conversation that doesn’t cement a child’s understanding of what happened in terms of absolute terms like good and bad. I see now that the terminology has more agency within it – there is more room for the child to decide if they felt safe, without feeling like the child itself is bad because of the abuse. To me, this approach seems more expansive, more appropriate. At the same time it also feels a bit like putting pressure on the child to decide if it was abuse or not. And I wonder, what can we do to deepen and expand our conversations about touch, rather than focus all our attention and all our fears on protecting children from abuse?I find myself leaning more and more towards talking to even a seven-year-old about consent. I don’t think many people approve of this route because they are focused on protection, anxious about controlling the environment around children – and often, children themselves. I choose it not because it is easy, but because it invests in the child’s sense of self. Teaching a child when she says no that I, an adult, am supposed to respect it, provides an opening for the child to learn behaviour that is useful in all negotiations, including sexual ones. In short, it strengthens agency of the child, and hopefully, equips them to look after themselves.The conversation on abuse often begins and ends with safety of the child. But the conversation on consent is a lifelong one. We begin it at an early age and continue it indefinitely. We teach the child not just about “touching of private parts” but non-consensual touch, through examples and our own lived experience.I learnt to tell my niece that she doesn’t need to hug me, if she doesn’t want to. How else will we build bodily autonomy? It makes me ask the question about why we work on sexuality education in the first place – is it to avoid abuse? Is it to allow people (children included) to explore their bodies and others (with consent)? I think the narrative shift happened in my own head when a few years ago my niece didn’t want me to touch her. I never found out the reason why, but she was stubborn about it and everyone around her told her that I was a “good person”, to try and convince her to get over her reluctance. I had to let her take her time to get over it. We as adults tend to take offence when children don’t hug us or we cannot pull their cheeks. But to me it’s pretty clear – if the child doesn’t learn that their opinion matters, the chances of the child reporting abuse or unsafe touch is far lower.Teaching them that when they say no, it means something and it will be taken seriously, has value for me. Teaching a child about respect, consent, bodily autonomy – even without these words – is hard and a longer process. But perhaps it’s worth it. Srinidhi Raghavan loves listening to stories. She is a part-time writer and full-time introvert. She works at the intersections of gender, sexuality, technology, rights and disability.

And so, for instance, how does this intersect with kinds of touch that society does not consider acceptable? Take masturbation, for example. This form of touch could be pleasurable for the adolescent learning to explore their body, but is often regarded as taboo and made out to be a kind of bad touch too. When sexual pleasure is almost never spoken of, and sexual touch is overwhelmingly tied up with shame, we need to think about how helpful it really is in this context to use the terms good touch and bad touch. Do we then end up doing more harm than good in the long run? Is good touch and bad touch, to put it simply, an incomplete education? Taught in a vacuum – in the absence of any comprehensive sexuality education, what does it really leave the child with?Back in 2009, Tulir, an organisation working to prevent child sexual abuse, began advocating for a shift in the language we use to discuss touch and abuse with children. They prefer the terms “safe touch”, “unsafe touch” and “confusing touch” as an opening for conversation that doesn’t cement a child’s understanding of what happened in terms of absolute terms like good and bad. I see now that the terminology has more agency within it – there is more room for the child to decide if they felt safe, without feeling like the child itself is bad because of the abuse. To me, this approach seems more expansive, more appropriate. At the same time it also feels a bit like putting pressure on the child to decide if it was abuse or not. And I wonder, what can we do to deepen and expand our conversations about touch, rather than focus all our attention and all our fears on protecting children from abuse?I find myself leaning more and more towards talking to even a seven-year-old about consent. I don’t think many people approve of this route because they are focused on protection, anxious about controlling the environment around children – and often, children themselves. I choose it not because it is easy, but because it invests in the child’s sense of self. Teaching a child when she says no that I, an adult, am supposed to respect it, provides an opening for the child to learn behaviour that is useful in all negotiations, including sexual ones. In short, it strengthens agency of the child, and hopefully, equips them to look after themselves.The conversation on abuse often begins and ends with safety of the child. But the conversation on consent is a lifelong one. We begin it at an early age and continue it indefinitely. We teach the child not just about “touching of private parts” but non-consensual touch, through examples and our own lived experience.I learnt to tell my niece that she doesn’t need to hug me, if she doesn’t want to. How else will we build bodily autonomy? It makes me ask the question about why we work on sexuality education in the first place – is it to avoid abuse? Is it to allow people (children included) to explore their bodies and others (with consent)? I think the narrative shift happened in my own head when a few years ago my niece didn’t want me to touch her. I never found out the reason why, but she was stubborn about it and everyone around her told her that I was a “good person”, to try and convince her to get over her reluctance. I had to let her take her time to get over it. We as adults tend to take offence when children don’t hug us or we cannot pull their cheeks. But to me it’s pretty clear – if the child doesn’t learn that their opinion matters, the chances of the child reporting abuse or unsafe touch is far lower.Teaching them that when they say no, it means something and it will be taken seriously, has value for me. Teaching a child about respect, consent, bodily autonomy – even without these words – is hard and a longer process. But perhaps it’s worth it. Srinidhi Raghavan loves listening to stories. She is a part-time writer and full-time introvert. She works at the intersections of gender, sexuality, technology, rights and disability.

By Srinidhi RaghavanIllustrated by Kruthika NS @theworkplacedoodlerI was having a conversation with my seven-year-old niece a few months ago when she told me that her school had introduced “good touch” and “bad touch” to her. As someone who talks about touch, sex, romance, consent on a regular basis, I asked her what she learnt. I was not surprised by her response: she summarised that all touching of her private parts was bad and all touching by “certain” members of the family/outsiders was bad. She told me that the examples given by her (well-meaning) teacher involved male figures harassing and preying on young girls. This teaching had resulted in her telling her grandfather not to touch her feet or her grandmother not to wash her during a bath.I remember asking my niece, “If I touch you, what does it make you feel?” She didn’t know what to answer. Even today, after several open discussions with her on touch and consent, I see her struggle with this, including with the idea of “strangers touching her” (which she’d been taught was bad) vs “known persons touching her” (which she’d been taught was okay).It’s understandable that teachers – and parents – would want kids to learn about different kinds of touch in order to help keep them safe. But I can’t help wonder if this “good touch” and “bad touch” business needs some rethinking.

By Srinidhi RaghavanIllustrated by Kruthika NS @theworkplacedoodlerI was having a conversation with my seven-year-old niece a few months ago when she told me that her school had introduced “good touch” and “bad touch” to her. As someone who talks about touch, sex, romance, consent on a regular basis, I asked her what she learnt. I was not surprised by her response: she summarised that all touching of her private parts was bad and all touching by “certain” members of the family/outsiders was bad. She told me that the examples given by her (well-meaning) teacher involved male figures harassing and preying on young girls. This teaching had resulted in her telling her grandfather not to touch her feet or her grandmother not to wash her during a bath.I remember asking my niece, “If I touch you, what does it make you feel?” She didn’t know what to answer. Even today, after several open discussions with her on touch and consent, I see her struggle with this, including with the idea of “strangers touching her” (which she’d been taught was bad) vs “known persons touching her” (which she’d been taught was okay).It’s understandable that teachers – and parents – would want kids to learn about different kinds of touch in order to help keep them safe. But I can’t help wonder if this “good touch” and “bad touch” business needs some rethinking. My niece’s confusion transports me back by six years to the first time I did a session on preventing child sexual abuse. I had said the same stuff about “good” and “bad” touch (it was an easy trap to fall into then, as it is now, especially since so much of the material we are provided around child sexual abuse uses this terminology). A short while after I finished the session and was packing my bag, a little girl, around 10 years old, walked up to me. She wanted to ask me what I meant by bad touch and how she was supposed to know it – the confusion on her face was remarkable. I myself was at a loss to respond helpfully, and I don’t think I provided her with a satisfactory answer.Years later, I still struggle to explain why I am uncomfortable with this terminology, but let me try.First, what is “good” touch? What is “bad”? How is a child supposed to determine this, and how do we teach them this without being broad and prescriptive in our explanation? One of my own fears about the way we advocate for good and bad touch is that the child may begin associating the touching of “private” parts with “bad”, and – therefore, all touching – with abuse. This association, even if made loosely, has confused many kids who I have worked with or spoken to.Second, considering that the perpetrators of abuse are often known to the victim, teaching kids this “known” vs “unknown” person dichotomy is pretty useless.Third, it is hard to assess how a child, any child, would respond to touch that is unwelcome. If it comes from a known person or is followed by a lot of grooming (that is, creating a bond and gaining a child’s trust in order to sexually abuse them), the child may not be in a place to identify the touch as “bad”. The experience of abuse itself sometimes makes it hard to not internalise shame – classifying it as “bad” only adds more guilt and shame into the mix, because a person may have experienced pleasure in a ‘wrong’ touch, which painfully complicates their sexual and psychological universe.To me, it sounds like a moral judgement is being made when we say good and bad touch – the language has a strong sense of what is supposed to be pleasurable and what is not, what is violent and what is not, and moral frameworks are not usually very helpful. Is all sexual touch bad? If it is bad, are we supposed to never get pleasure from it? Are we supposed to automatically feel discomfort if we are touched by a stranger, even if the touch is not sexual? How does this shape an overall perspective on sex?What then do we do when a 16-year-old child encounters touching of the private parts and feels pleasure? Are we to determine by our standards that it is harassment because they are 16 – since the law says so? Or is it not harassment because the child felt pleasure? The answers are not easy – in fact they are context dependent, but we don’t talk about these things enough, in a world where we also don’t talk about sex enough.

My niece’s confusion transports me back by six years to the first time I did a session on preventing child sexual abuse. I had said the same stuff about “good” and “bad” touch (it was an easy trap to fall into then, as it is now, especially since so much of the material we are provided around child sexual abuse uses this terminology). A short while after I finished the session and was packing my bag, a little girl, around 10 years old, walked up to me. She wanted to ask me what I meant by bad touch and how she was supposed to know it – the confusion on her face was remarkable. I myself was at a loss to respond helpfully, and I don’t think I provided her with a satisfactory answer.Years later, I still struggle to explain why I am uncomfortable with this terminology, but let me try.First, what is “good” touch? What is “bad”? How is a child supposed to determine this, and how do we teach them this without being broad and prescriptive in our explanation? One of my own fears about the way we advocate for good and bad touch is that the child may begin associating the touching of “private” parts with “bad”, and – therefore, all touching – with abuse. This association, even if made loosely, has confused many kids who I have worked with or spoken to.Second, considering that the perpetrators of abuse are often known to the victim, teaching kids this “known” vs “unknown” person dichotomy is pretty useless.Third, it is hard to assess how a child, any child, would respond to touch that is unwelcome. If it comes from a known person or is followed by a lot of grooming (that is, creating a bond and gaining a child’s trust in order to sexually abuse them), the child may not be in a place to identify the touch as “bad”. The experience of abuse itself sometimes makes it hard to not internalise shame – classifying it as “bad” only adds more guilt and shame into the mix, because a person may have experienced pleasure in a ‘wrong’ touch, which painfully complicates their sexual and psychological universe.To me, it sounds like a moral judgement is being made when we say good and bad touch – the language has a strong sense of what is supposed to be pleasurable and what is not, what is violent and what is not, and moral frameworks are not usually very helpful. Is all sexual touch bad? If it is bad, are we supposed to never get pleasure from it? Are we supposed to automatically feel discomfort if we are touched by a stranger, even if the touch is not sexual? How does this shape an overall perspective on sex?What then do we do when a 16-year-old child encounters touching of the private parts and feels pleasure? Are we to determine by our standards that it is harassment because they are 16 – since the law says so? Or is it not harassment because the child felt pleasure? The answers are not easy – in fact they are context dependent, but we don’t talk about these things enough, in a world where we also don’t talk about sex enough. And so, for instance, how does this intersect with kinds of touch that society does not consider acceptable? Take masturbation, for example. This form of touch could be pleasurable for the adolescent learning to explore their body, but is often regarded as taboo and made out to be a kind of bad touch too. When sexual pleasure is almost never spoken of, and sexual touch is overwhelmingly tied up with shame, we need to think about how helpful it really is in this context to use the terms good touch and bad touch. Do we then end up doing more harm than good in the long run? Is good touch and bad touch, to put it simply, an incomplete education? Taught in a vacuum – in the absence of any comprehensive sexuality education, what does it really leave the child with?Back in 2009, Tulir, an organisation working to prevent child sexual abuse, began advocating for a shift in the language we use to discuss touch and abuse with children. They prefer the terms “safe touch”, “unsafe touch” and “confusing touch” as an opening for conversation that doesn’t cement a child’s understanding of what happened in terms of absolute terms like good and bad. I see now that the terminology has more agency within it – there is more room for the child to decide if they felt safe, without feeling like the child itself is bad because of the abuse. To me, this approach seems more expansive, more appropriate. At the same time it also feels a bit like putting pressure on the child to decide if it was abuse or not. And I wonder, what can we do to deepen and expand our conversations about touch, rather than focus all our attention and all our fears on protecting children from abuse?I find myself leaning more and more towards talking to even a seven-year-old about consent. I don’t think many people approve of this route because they are focused on protection, anxious about controlling the environment around children – and often, children themselves. I choose it not because it is easy, but because it invests in the child’s sense of self. Teaching a child when she says no that I, an adult, am supposed to respect it, provides an opening for the child to learn behaviour that is useful in all negotiations, including sexual ones. In short, it strengthens agency of the child, and hopefully, equips them to look after themselves.The conversation on abuse often begins and ends with safety of the child. But the conversation on consent is a lifelong one. We begin it at an early age and continue it indefinitely. We teach the child not just about “touching of private parts” but non-consensual touch, through examples and our own lived experience.I learnt to tell my niece that she doesn’t need to hug me, if she doesn’t want to. How else will we build bodily autonomy? It makes me ask the question about why we work on sexuality education in the first place – is it to avoid abuse? Is it to allow people (children included) to explore their bodies and others (with consent)? I think the narrative shift happened in my own head when a few years ago my niece didn’t want me to touch her. I never found out the reason why, but she was stubborn about it and everyone around her told her that I was a “good person”, to try and convince her to get over her reluctance. I had to let her take her time to get over it. We as adults tend to take offence when children don’t hug us or we cannot pull their cheeks. But to me it’s pretty clear – if the child doesn’t learn that their opinion matters, the chances of the child reporting abuse or unsafe touch is far lower.Teaching them that when they say no, it means something and it will be taken seriously, has value for me. Teaching a child about respect, consent, bodily autonomy – even without these words – is hard and a longer process. But perhaps it’s worth it. Srinidhi Raghavan loves listening to stories. She is a part-time writer and full-time introvert. She works at the intersections of gender, sexuality, technology, rights and disability.

And so, for instance, how does this intersect with kinds of touch that society does not consider acceptable? Take masturbation, for example. This form of touch could be pleasurable for the adolescent learning to explore their body, but is often regarded as taboo and made out to be a kind of bad touch too. When sexual pleasure is almost never spoken of, and sexual touch is overwhelmingly tied up with shame, we need to think about how helpful it really is in this context to use the terms good touch and bad touch. Do we then end up doing more harm than good in the long run? Is good touch and bad touch, to put it simply, an incomplete education? Taught in a vacuum – in the absence of any comprehensive sexuality education, what does it really leave the child with?Back in 2009, Tulir, an organisation working to prevent child sexual abuse, began advocating for a shift in the language we use to discuss touch and abuse with children. They prefer the terms “safe touch”, “unsafe touch” and “confusing touch” as an opening for conversation that doesn’t cement a child’s understanding of what happened in terms of absolute terms like good and bad. I see now that the terminology has more agency within it – there is more room for the child to decide if they felt safe, without feeling like the child itself is bad because of the abuse. To me, this approach seems more expansive, more appropriate. At the same time it also feels a bit like putting pressure on the child to decide if it was abuse or not. And I wonder, what can we do to deepen and expand our conversations about touch, rather than focus all our attention and all our fears on protecting children from abuse?I find myself leaning more and more towards talking to even a seven-year-old about consent. I don’t think many people approve of this route because they are focused on protection, anxious about controlling the environment around children – and often, children themselves. I choose it not because it is easy, but because it invests in the child’s sense of self. Teaching a child when she says no that I, an adult, am supposed to respect it, provides an opening for the child to learn behaviour that is useful in all negotiations, including sexual ones. In short, it strengthens agency of the child, and hopefully, equips them to look after themselves.The conversation on abuse often begins and ends with safety of the child. But the conversation on consent is a lifelong one. We begin it at an early age and continue it indefinitely. We teach the child not just about “touching of private parts” but non-consensual touch, through examples and our own lived experience.I learnt to tell my niece that she doesn’t need to hug me, if she doesn’t want to. How else will we build bodily autonomy? It makes me ask the question about why we work on sexuality education in the first place – is it to avoid abuse? Is it to allow people (children included) to explore their bodies and others (with consent)? I think the narrative shift happened in my own head when a few years ago my niece didn’t want me to touch her. I never found out the reason why, but she was stubborn about it and everyone around her told her that I was a “good person”, to try and convince her to get over her reluctance. I had to let her take her time to get over it. We as adults tend to take offence when children don’t hug us or we cannot pull their cheeks. But to me it’s pretty clear – if the child doesn’t learn that their opinion matters, the chances of the child reporting abuse or unsafe touch is far lower.Teaching them that when they say no, it means something and it will be taken seriously, has value for me. Teaching a child about respect, consent, bodily autonomy – even without these words – is hard and a longer process. But perhaps it’s worth it. Srinidhi Raghavan loves listening to stories. She is a part-time writer and full-time introvert. She works at the intersections of gender, sexuality, technology, rights and disability.