Some people know Shruti as Dr. Shruti Chakravarty, a therapist working in the non-profit sector on mental health, gender and sexuality, for two decades now. Shruti is currently the Chief Advisor at Mariwala Health Initiative and also faculty at the Queer Affirmative Counselling Practice course they run. Others know Shruti as - @pawlyamorous her Insta handle, filled with everyday moments from her life and of her relationship – selfies, photos of a partner, outdoor walks, pets, work-related events - beloved of many young queer people online for its unabadhed romanticism, its positive world of a possible queer life. Shruti calls herself a good old fashioned butch, a lesbian, a masculine cis-woman.In this interview with AOI she takes us through her life were she became all these selves and more, with a little help from through love, sex, romance, friendship, community, politics - and more. Read on to get to know, another fabulous #GrownAssWoman who helps you imagine a different future than society suggests you can have.

Your Instagram is filled with lovely, romantic photographs of your partner Pooja and you. Do you have a definition of love?

Yes, we do have a definition of love. Pooja proposed it and I love it. The four words that we use to define love are ‘passionate’, ‘poetic’, ‘sensible’ and ‘healing’. I continue to stick by them. For me, love also involves a lot of romance. It is harmony. I want love to feel good, you know. I know it doesn’t always. But in my mind, I feel like it should. And because I am butch, love should make me feel that my femme (a feminine lesbian woman) is the most attractive and that I will love her forever (laughs).

Your social media bio says you are an ‘old-fashioned butch’. How did you arrive at this label of ‘butch’? And why is it so important to describe yourself thus?

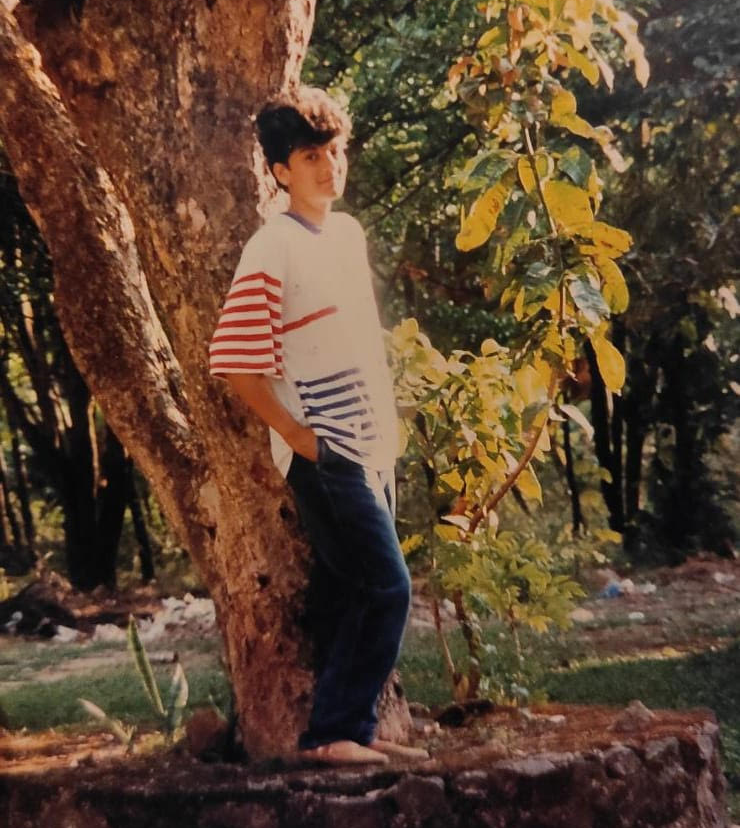

As you can well imagine, reaching a label, an identity takes time. At first, I used to call myself a ‘tomboy’. I knew I was a tomboy right from the age of 13. I also knew I was attracted to girls since then. Although I didn’t have the language that I do now, I would live my little baby-lesbian life with the other girls in my class and have crushes on female teachers. Since I was the only tomboy in school, I had a lot of attention from the girls. This was 1992-93. There would be comparisons to film heroes and heroines, like you (Shruti) were the actor from a popular film, and the girl would say, ‘I am your wife’ or ‘I am your heroine’. It was mainly a heterosexual replication of the hero-heroine or husband-wife idea. Only, it was between girls.

I mean, I had started understanding what was going on not so much in my mind, but in my body. My body was responding through orgasms and touching each other more fully. The only thing we knew at that time was this is shameful, dirty, horrible and I’m such a bad person because I can’t stop myself.

I was about 23 or 24 when I learnt about sex positivity, that sex as pleasure was something I could own and explore. After I met the queer collective and had more opportunities to explore my sexuality, I understood what sex could entail – its space and expansiveness. That it’s not just about a penis penetrating a vagina. It’s about what intimacy means to me, what gives me pleasure. With the queer-feminist collective, I also had role models of queer women walking on the streets. It was all marvellous!

You also call yourself an ‘old-fashioned butch’. What does that mean?

An old-fashioned butch in my mind – which I am – is somewhat gentlemanly and chivalrous. She wears masculine clothing, for sure. I really wouldn’t mind the whole tie-jacket look. Really short hair like my salt and pepper look. Old fashioned also in terms of how I relate to my femme. Within the queer community, we have this idea of ‘a full-service butch’. It means a butch who will offer herself completely to be there for the femme. I’m not at that level, nor do I want to be. It’s just in the style, how your femme is most important to you and you will do everything grand in your life to make her feel grand. Of course, we don’t live it out like that on an everyday basis (laughs). But, for me, loving a woman is the most glorious gift I could’ve got.

Would you call yourself successful in flirtation?

I would think so. My self-esteem and self-worth were so good during my teenage years because of all the attention I got in school. I carried it well into my late 20s and early 30s. I was the popular butch and like a magnet to straight women and femmes, a real stud (laughs). In Bombay, I would go to many gay men parties where there would be a few women too. At that time, I was very happy with my body. I was lean so I felt I was attractive. I was very confident in how I moved my body, in my dancing. I could talk a lot. I had stories to tell, so my social skills were working for me. Also, I am very gentlemanly and charming and I would be quite upfront in telling someone if I was interested. If the woman said no, then I would back off. Of course, it wasn’t always a direct ‘yes’ or ‘no’, but I preferred to keep things clear right from the beginning because that helps. Sometimes there were the ‘Let’s see how this goes’ or ‘We’ll figure it out’. But I found that that method worked for me. A lot of it changed in my mid-30s.

Why? What happened then?

As my body began to change, it impacted my masculinity. Growing a bit round rather than lean made me feel like I was not looking the way I wanted to. I used to think that my butch life is now over and women aren’t going to find me attractive. Around 35, I fell in love with a straight, married woman and that did me a lot of damage, unfortunately. In the way she was relating to me, I was her man. The way she treated me, the power she attributed to me, was like a man in the traditional sense. Because I began to perceive myself through that gendered filter, I felt worse and worse about my masculinity. I never identified as a man in that sense, and I began to feel uncomfortable, uncertain about the way I expressed my gender. It was something that I had loved and built for myself. And that had begun to crumble. In those years I stopped using the word ‘butch’ for myself. After I finally got out of that relationship, and later also met my partner Pooja, I was slowly able to find myself again and reclaim my masculinity in very affirming ways. I think our intimate partners play a huge role in how we perceive ourselves. Especially, as a butch woman, when there aren’t enough role models out there to say ‘Butch is great!’, ‘Butch is good-looking’, ‘Butch is not ugly’.

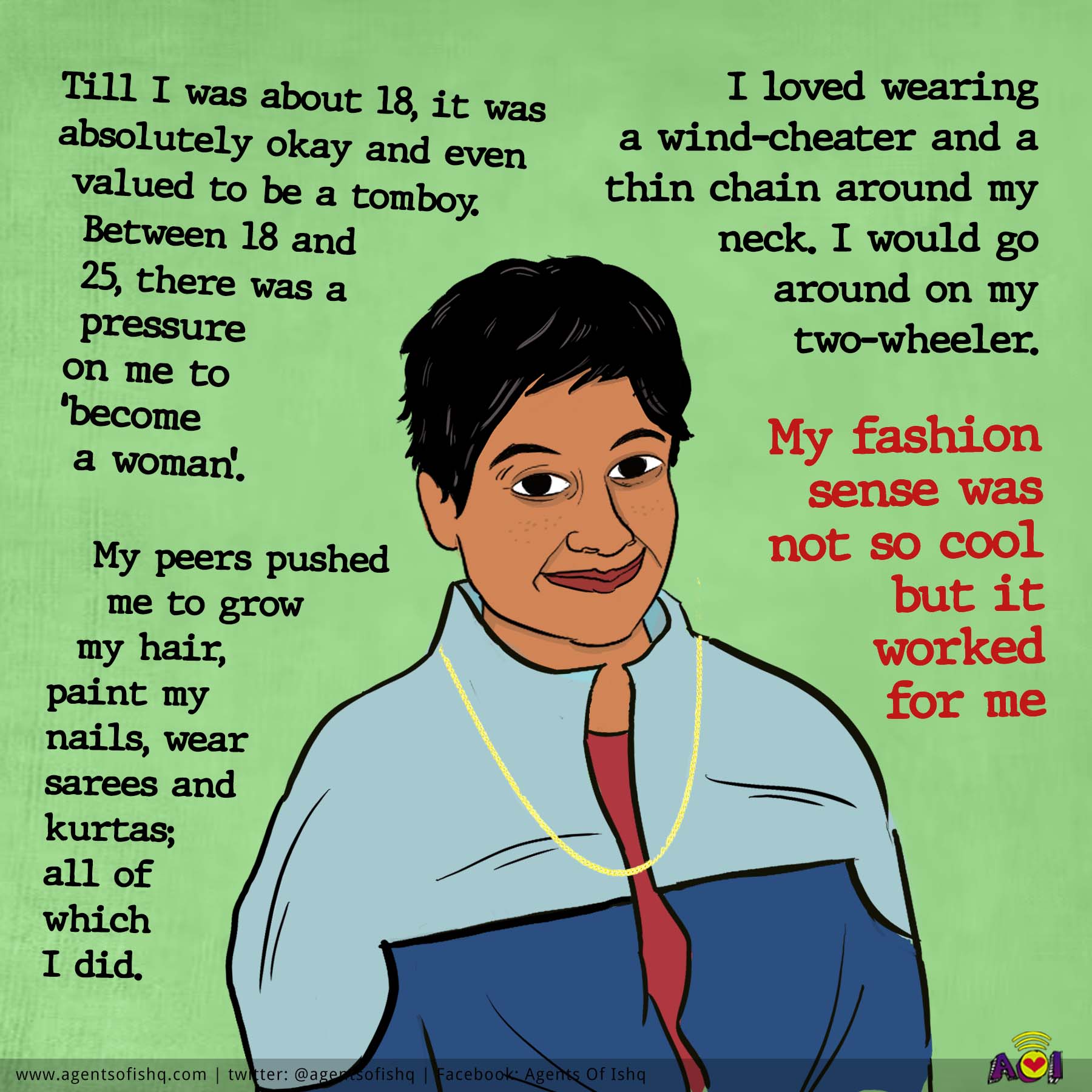

Have you ever faced any pressure to be feminine?

Till I was about 18, it was absolutely okay and even valued to be a tomboy. Between 18 and 25, there was a pressure on me to ‘become a woman’. I was told not to be like a man or dress like a man. My peers pushed me to grow my hair, paint my nails, wear sarees and kurtas; all of which I did. Personally, I loved wearing a wind-cheater and a thin chain around my neck. I would go around on my two-wheeler. Coming from a small town, my fashion sense was not so cool but it worked for me.

Also, it’s always about this gender binary, right? If you’re not feminine, then you are a man. So, to claim ‘butch’ as a masculine woman has been a struggle for me. The conflation of masculinity equal to man is something that I’ve had to push back on. As I got more steeped in my work, training and activism, and began talking about gender, sexuality and politics, it got slightly easier. I began feeling a little proud of myself and more okay with the way I was.

What about people outside your immediate circle? How do they react?

Usually when I go to a party and go to the ladies’ bathroom, the women get startled because they think a man has walked in and it makes them very uncomfortable which also makes me uncomfortable. So, I try all kinds of tricks. If I have a feminine woman walk in with me, that helps. A really funny incident with a gynaecologist in my early 20s — I had gone with my partner at the time. After checking us one after the other, the gynaec said, “It’s so surprising! Both of you have the same infection.” I mean, I looked the way I do and she still didn’t make the connection! It was hilarious! (laughs).

Has being a masculine woman allowed you any of masculinity’s advantages?

Unlike with cis-het men, there is no real power that masculinity bestows on women who are masculine. Because masculinity in a woman is always considered ugly or scary. But I think when you break away from the set gender norms, you allow yourself more permissions. I’ve often heard Pooja say that because she was so gender conforming, so feminine, she kept thinking she was heterosexual. Because she felt she was up for consumption only from the male gaze, from [cis-het] men. Even in my case, I used to think that if I was feminine, I would be a heterosexual. If I was lesbian, then my gender expression had to be something else. So, for Pooja, the journey has been such that femme-lesbian is the only identity that fits because being lesbian and femme exist together for her. Besides gender norms, if you also break sexuality norms, you allow yourself some more permissions to be the way you want to be. In that sense, I have had that opportunity, for sure. Also, butches don’t age the way that typical feminine women might because there are certain indicators and milestones for ageing. Since I’m already out of that script or defined idea of femininity, the same standards may not apply. My salt and pepper hair, for example, can appear more sexy and all of that. I’ve had people tell me, “Oh, you are growing hotter with age”.

You’ve repeatedly mentioned how deeply the queer collective you were a part of influenced you. What is the importance of encountering collectives or organisations?

The collective was a very important starting point for me to learn to be myself. From its inception in 1995, I think, this was a group that had always defined itself as ‘queer feminist’. So, my queer or lesbian journey and my feminist politics started together. It gave me the opportunity to understand my sexuality and gender through a feminist lens. Back then, we only used the word ‘women’. We didn’t have the words ‘non-binary’ or ‘gender fluid’. I mean, those identities were there but the labels weren’t. I didn’t have much access to books or reading at the time. So much of becoming queer or learning the possibilities of surviving a queer life or struggle came from meeting people and watching them go through those things. I remember, in my early 20s, there was an older dyke in her mid-30s in the collective. She used to walk the train stations and streets wearing a shirt and shorts. I had actually asked her, “How do you have the guts?” (laughs). She gave me such a look of “What is your question even? Why would I get harassed?” But in my baby-butch mind, I was like how does she move around in the world looking like that? Little did I know that I would be doing exactly that in a few years’ time. At the time, I was in a bit of a crisis with my then-girlfriend. It was a traumatic time, I was so broken, and these older dykes in the collective just swooped in to help me. One woman would say, “You are staying with me for the next three days” and after those 2-3 days, another one would say, “Okay, now you are staying with me. Don’t stay alone”. I think I lived like that for almost a month and I was able to garner some strength, some resources to hold myself together. Just the fact that these dykes were looking out for me in that very crucial period meant so much at that age. Even money-wise, you know. Many of the older queers would pay for the entry into some party. After meetings, they would feed us dinner because they knew ghar pe toh khana hoga nahin aur paise toh nahin hai khane ke (There is no food at home and no money to eat out). They would buy us the drinks because, you know, drinking was also part of bonding and taking care of each other. It meant I could be young, foolish, adventurous. This is something that I have learned from and also offered to younger queer people. When I have the money, there are many younger queer folks to whom we say, “Don’t worry we will get the drinks, let’s go for this party” or “I will pay for the tickets” . As a collective, all the crisis intervention we continue to do – helping women out of bad marriages, hostile or violent homes, going with them to the police station, comes from this idea of creating a space that they didn’t have before.

Do you think younger queer people today have similar ideas of a collective?

I don’t know whether they are really meeting each other the way we did as queer people. Most meetings happen through social media and I mean, it’s also a pandemic now. While they seem more connected, I wonder if younger queers today feel lonely. While there are more role models in terms of more visibility and representation because of social media today, I wonder how much of it translates into the feeling of I know this person, and I have spent time with them. Speaking of myself, a lot of the content that I put out on social media comes from the space that I've lived a certain way, that I’ve had a certain journey and I’ve got here with certain struggles. The role modelling I can offer as an older person is something I would like to offer. And I’ve found that young people have responded to that positively.

But there is a big change in how people think about labels and choose to identify with them, right?

I think our understanding of gender – especially within the queer-trans community, is expanding today. The more we question the binary and talk of gender as multiple, the more we say that the binary itself is restricting. And because of that, certain identities which would indicate a cis-ness are now, perhaps, seen as outdated, controversial, limiting, or even erasing of other identities. Personally, however, I do feel that we live in a society with very few role models available to us. How to be a masculine woman, how to love as a lesbian, how to be alive – we don't know that. Nobody's talking about it. We are only taught to be heterosexual, right? So then, as we are navigating such a world, we find labels as we make meanings. I think it's a bit unfair to say that certain labels are outdated, old fashioned or irrelevant in today's newer understandings of gender. I don't think that if I say ‘butch’, I am not aware of transpersons or non-binary people. I’m just claiming that label for myself by saying that I am indeed cis and I recognise the privileges of that. I’m also not a gender-conforming woman. To me, no other word fits, but ‘cis butch lesbian’. ‘Lesbian’ is also, I think, considered outdated today because you're now saying ‘woman loving woman’. I think we need to expand these conversations. And a queer space is the only one where such inclusivity and diversity can happen. Queer in itself means that. So, I feel that outdated terms should exist as validly as others.

We’re living in a time when the number of young people in the world is more than ever. In the queer context, how do you think that plays out? Is there a certain pushback to the authority of age, for instance?

Personally I don’t experience it as much, because of how integrated I am now. But, as a trend, or a way of being in the world, yes, I do feel that there is a lot of focus on young people, on young people’s issues. And maybe, there is a certain pushback by young people against older people. I once got an email that said, “As an icon of an older generation, we would like to talk to you…” It was a favourite! (laughs) So I do get that I'm being perceived as old. But what I have also done is that I’ve owned being older, because I have felt older. About the older queers, where are they really? Within our queer feminist political circles, we have the older queers, sure. Those of us who were in our 20s are now well into our 40s, and those who were 40 back then and now well into their 60s. We are connected only in terms of our activism. But otherwise, the older queers are barely visible. On social media, in meetings and collectives, there are mostly younger people. I believe this brings a lot of loneliness for the older queers. They may not be as connected because they may not be social media savvy. They may be more afraid because they are entrenched in family systems and lives which may make it harder for them to be visible. Recently, when we had a memorial for a friend who had passed away, a lot of the queer people I hadn’t met since my 20s turned up to pay their respects. There, we asked them where they had been for the last 10-15 years? What was going on in their lives? Some people said that they couldn’t go to parties anymore because they were full of younger people. There were also stories of heartbreak. Many older queers had relationships in their 20s and 30s that didn’t work out as they grew older for various reasons. A lot of women get into heterosexual or heteronormative marriages because they are pressurized to do so or because they don’t see possibilities of living a queer life. So, a lot of older queers are left alone. Besides networking and finding partners, I think we definitely aren’t talking about health. What are masculine women like me doing? Where are they seeking help from? If one went, say, to a gynaecologist, what kind of hostility might they be facing?

How do you feel at this point in your life?

I have been very excited to get to 40. Turning 40 gave me a sense of integration internally, of my different selves. All my struggles with gender, with sexuality, with finding love, my career, getting my PhD…all of them finally felt like they had come together and I was where I wanted to be. I almost feel like I’m now going to live again, like an older dyke in my 40s and 50s.

What would you say is the best compliment you have received till date?

I love being called charming. When a woman tells me that I’m charming or she is charmed by me or that she finds me attractive because I paid her a very focused kind of attention, I love that. That is my goal. I love to please women.

What is something unlikeable about you?

People don’t like that I’m very direct in the way I speak. While I can be very good at setting boundaries, it can also come off as rejection. I can be very vocal about my disapproval.

What would you say is wonderful about you?

I think it would be that I’m loyal. From others, I’ve heard that I’m charming, reliable, easy to be around, fun to be with. I’ve also heard from people that I can bring a strengthening presence to someone’s life. Maybe because of the way I’ve survived my own life, and the work I do as a therapist, I might bring a certain ease and strength.

Is there anything you want to work on, say in the next ten years? Any medium-term dreams?

I’ve hopefully put my troubles with gender and sexuality to rest. My main concern is my physical health because I am ageing and I didn’t really take care of my body in my 20s and 30s. I did a lot of drinking and late nights. All the emotional struggles also battered me. So, I have started eating a better diet, doing some exercise. Medium-term dream would be to focus on my career. I feel that, earlier, I was too caught up with being queer and all the upheavals that came with it that I didn’t pay my career enough attention.

And beyond? Say for when you’re 70?

I haven’t really thought very far ahead. I don’t know if it’s a queer thing that we don’t think of ourselves in any long-term ways because the everyday can be a struggle. But as someone who thinks in a very relational manner, I can imagine growing old with a partner. The one dream I do have is that I want to grow old with Pooja. I haven't really thought about how my life might look at 70. Although I don’t think I’ll change much. I’ll continue to wear my shirts, and more comfortable pants perhaps.