When it comes to learning about our bodies, thinking about gender and sexuality or making decisions about love and romance and pleasure, we need a few things: honesty, openness, and access to information. In a world where we can have access to information - for instance, through sex-education - and the opportunity to discuss how we feel about that information - which means a cultural context free of judgement and shame, we have a greater chance of health, happiness, equality and freedom.We know that the Indian Constitution upholds the right to equality and right to freedom. Free speech and access to information have been democratic rights many people have fought to keep alive. And yet, there are laws that somehow seem to contradict and restrict these things, especially when it comes to sex and sexual expression. When we look at laws governing sexual expression, we see two things: a squeamishness with sex, and the treating of adults as children who cannot make their own decisions of what is appropriate or not. This is doubly true for women, who are treated like masoom, bholi, innocents whose honour needs to be protected.Where did this funda come from? Well, in part it is rooted in the colonial-era approach of treating ‘natives’ as uncivilized, backward children who need guidance. Cinema came to India as soon as it was invented and created a sensation. Soon after a committee was set up to figure out whether Indians should have parental guidance - matlab colonial guidance for watching films. In the late 1920s,the Indian Cinematograph Committee published a report on the matter. In it’s opening pages, the report said that censorship may not be necessary in other parts of the world, but, “as far as India is concerned, public opinion is not sufficiently organised or articulate to make it possible to dispense with censorship.”In many ways these attitudes have determined laws. And they also start shaping the public culture. So today too we have other forms of censorship which control how frank or bold we can be. It may be in the form of trolling which is a kind of censorship or censoriousness too. It can be seen in the form of "community" standards and policies (like Facebook’s blocking of even educational content about sex) or Agents of Ishq being blocked in so many offices and colleges. Hello, kya agents are not part of the community?Let's check out some of India’s laws and policies that censor expression about intimate and erotic life:

* * * It’s hard to define what constitutes “depravity”, “morality”, “decency”, or even “good taste” – none of these come with instruction manuals. So it’s strange that laws and policies, and sometimes “community standards”, should rely on these ideas to judge what is acceptable or not. We need to change the frame by focusing on consent - in the creation of material and in its depiction. We need for sex education so people can be at ease with deciding what feels ok for them and what does not.What’s more, criminalising depictions of sex and sexuality enforce the idea that it is something to be hidden or ashamed of, and may stop people from seeking crucial information, such as about reproductive health, even when they really need it. For everyone to be armed with the information they need, we need less censorship, not more.

* * * It’s hard to define what constitutes “depravity”, “morality”, “decency”, or even “good taste” – none of these come with instruction manuals. So it’s strange that laws and policies, and sometimes “community standards”, should rely on these ideas to judge what is acceptable or not. We need to change the frame by focusing on consent - in the creation of material and in its depiction. We need for sex education so people can be at ease with deciding what feels ok for them and what does not.What’s more, criminalising depictions of sex and sexuality enforce the idea that it is something to be hidden or ashamed of, and may stop people from seeking crucial information, such as about reproductive health, even when they really need it. For everyone to be armed with the information they need, we need less censorship, not more.

The Cinematograph Act, 1952

The Cinematograph Act and its associated regulations relate to censorship of films. It empowers a body called the Central Board of Film Certification, whose pet name is Censor Board, to censor parts of films or ban them for reasons including going against “decency and morality” and to maintain order and prevent crime. Hai decency, our open-ended friend. Hai morality, every Indian ka school principal.This Act is a colonial hand-me-down and has an interesting history.Guess when it first came about? In the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in 1918, when the British were trying to stop the spread of information through newspapers and film. Ahem.But somehow, in political repression, a little morality also was squeezed in. Nudity was originally banned, but in 1956, an exception was made: bare breasts could be shown in documentaries about ‘primitive’ people, perhaps because they indigenous people were not seen as equal citizens – another colonial inheritance, as the late film critic Kobita Sarkar pointed out.In her book about films and censorship, Sarkar, who had also served on the Advisory Panel of the CBFC in the 1960s and 70s, said that to the Board, morality meant sexual morality. She wrote this about an instance in which a second kissing scene was cut out of a foreign film: “‘It's too much!’ ‘Why,’ I asked, truly perplexed. ‘One kiss is enough,’ said the first member flatly. ‘It's vulgar. The girl is enjoying herself!’”Sarkar’s accounts show just how subjective “morality” is when she talks about how male chauvinistic attitudes prevailed in censorship: when a man was seen to commit adultery in film, it was allowed to slide, but a woman had to die or be punished for it. Even though sex wasn’t allowed, rape could be portrayed. And she highlights another strange trope: “All sorts of sexual cavorting was justified if it was cloaked in a mythological garb.”Ideas of “morality” change with time. Where a kiss in Bollywood could once be depicted only through flowers touching, kissing on the lips or depicting pre-marital sex in film is no longer uncommon, though the logic for why some scenes make it and some don’t still remains unclear (see former CBFC chief Pahalaj Nihalani’s reasoning for why some kinds of kisses were allowed in Befikre but not Ae Dil Hai Mushkil). But even if things may be different now than they were 30 years ago, euphemisms and double meanings are still more prevalent than frank, grown-up sexualness in film.

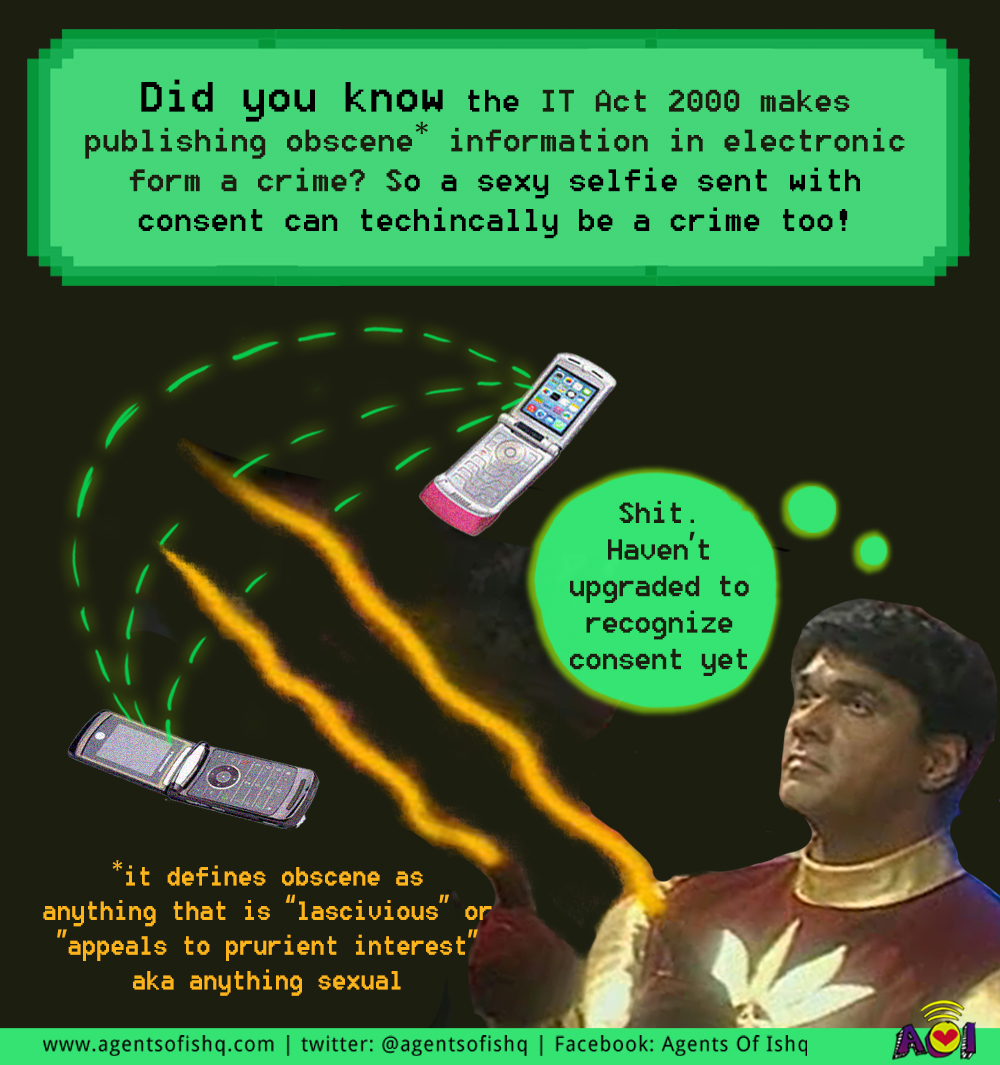

The Information Technology Act, 2000

This Act governs a very broad range of online activities. Some aspects of it are related to curbing crimes like the creation or sharing of child porn and the capturing or sharing of images of a person’s private parts without their knowledge or consent. However, it leaves some loopholes which criminalise other kinds of sexual content even when shared with consent (remember, treating adults like children vali baat?).According to Section 67 of this Act, publishing “obscene” information in electronic form, or images containing sexual acts, is a crime. This includes any material that is “lascivious” or “appeals to the prurient interest” – yaniki, anything that is sexual in nature – or has an effect that is likely to “deprave and corrupt” people. This potentially brings a very wide range of things online related to sex or sexuality, (from, say, erotic fiction to a sexy selfie sent and received with consent) under its scanner.As filmmaker and activist Bishakha Datta points out in this video below, when we use the lens of obscenity instead of the lens of consent, to determine a crime, the IT Act actually ends up taking away a woman’s agency. It implicates her in the crime when anything to do with sex is automatically in the obscenity or ashleelta cateogry which might harm the "public morality" (remember that treating 'natives' and 'subjects' as uncivilised children vali baat?). Therefore it fails to acknowledge that harm was done to an individual and might even harm that person further.

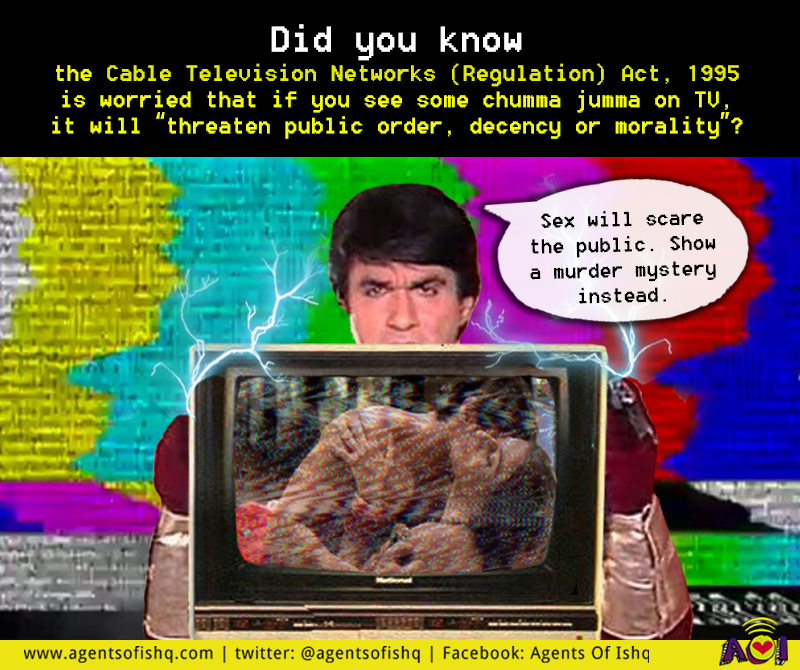

The Cable Television Networks (Regulation) Act, 1995

This Act prohibits transmission of a channel or programme for a range of reasons from voicing criticism of friendly countries to threatening “public order, decency or morality”. It has an accompanying set of Cable Television Networks Rules, which says that no programme should be carried if it “offends against good taste or decency”. This is tricky, pyaari agents, because good taste and decency depend completely on the person you are asking! (What if you believe that Abhishek Bachchan’s outfits in Drona violate good taste and decency?) The Act and Rules also criminalise “anything obscene” and “suggestive innuendos” – the latter could potentially apply to every Bollywood movie ever made! There isn’t a separate regulatory body to enforce this, so it puts broadcast under direct control of the State. That is, the government gets to decide what you can and can’t watch on TV.But broadcasters can also be enthu on their own and do things like starring out some words in the subtitles of English language programs. Some examples of words that are starred out - ovaries, periods, sex (even if used in the sense of a person's biological sex). Any coincidence ki some of these words are just to do with female reproductive biology?

Section 292 of the Indian Penal Code

This Section of the IPC bans the sale or circulation of “obscene” books, pamphlets, materials, paintings. It is enforced by the police and judicial system, and has been used in a range of scenarios from charging a rapist who tried to shame his victim by putting “obscene” photographs of her on the walls of her home to charging writer Vasant Gurjar for his Marathi poem I Met Gandhi. In 2015, the Supreme Court said that freedom of speech and expression was not “absolute” and obscene words could not be used for a historical person like Mahatma Gandhi, adding that Gurjar would have to face trial. Gurjar’s case shows that sometimes, what is deemed unacceptable depends entirely on the context in which it takes place.And sometimes this context changes, as a 2014 Supreme Court judgement noted while delivering its judgement on a long-pending case against a magazine that ran a photograph of tennis player Boris Becker posing with his then fiancee Barbara Feltus. Though both were nude, with only his arms covering her breasts, it wasn’t an overtly sexual photo. The court rejected the arguments against the photo and said, “A picture of a nude/semi-nude woman … cannot per se be called obscene… the obscenity has to be judged from the point of view of an average person, by applying contemporary community standard(s).”

Porn Ban

There are no laws in India that are against watching pornography in private, though making and distributing pornographic material is a crime. But in 2015, the government blocked over 800 porn and file-sharing websites, and has made renewed efforts to block porn sites in 2018 and 2019. One reason cited for this is that the government is trying to curb the viewing and sharing of child porn, which is a criminal offence, and about which the Department of Telecom has instructed internet service providers like Jio and Airtel. But it is unclear why this ban has extended to so many other porn sites, especially some of the bigger ones that moderate their content, because this has not been a blanket ban. * * * It’s hard to define what constitutes “depravity”, “morality”, “decency”, or even “good taste” – none of these come with instruction manuals. So it’s strange that laws and policies, and sometimes “community standards”, should rely on these ideas to judge what is acceptable or not. We need to change the frame by focusing on consent - in the creation of material and in its depiction. We need for sex education so people can be at ease with deciding what feels ok for them and what does not.What’s more, criminalising depictions of sex and sexuality enforce the idea that it is something to be hidden or ashamed of, and may stop people from seeking crucial information, such as about reproductive health, even when they really need it. For everyone to be armed with the information they need, we need less censorship, not more.

* * * It’s hard to define what constitutes “depravity”, “morality”, “decency”, or even “good taste” – none of these come with instruction manuals. So it’s strange that laws and policies, and sometimes “community standards”, should rely on these ideas to judge what is acceptable or not. We need to change the frame by focusing on consent - in the creation of material and in its depiction. We need for sex education so people can be at ease with deciding what feels ok for them and what does not.What’s more, criminalising depictions of sex and sexuality enforce the idea that it is something to be hidden or ashamed of, and may stop people from seeking crucial information, such as about reproductive health, even when they really need it. For everyone to be armed with the information they need, we need less censorship, not more.